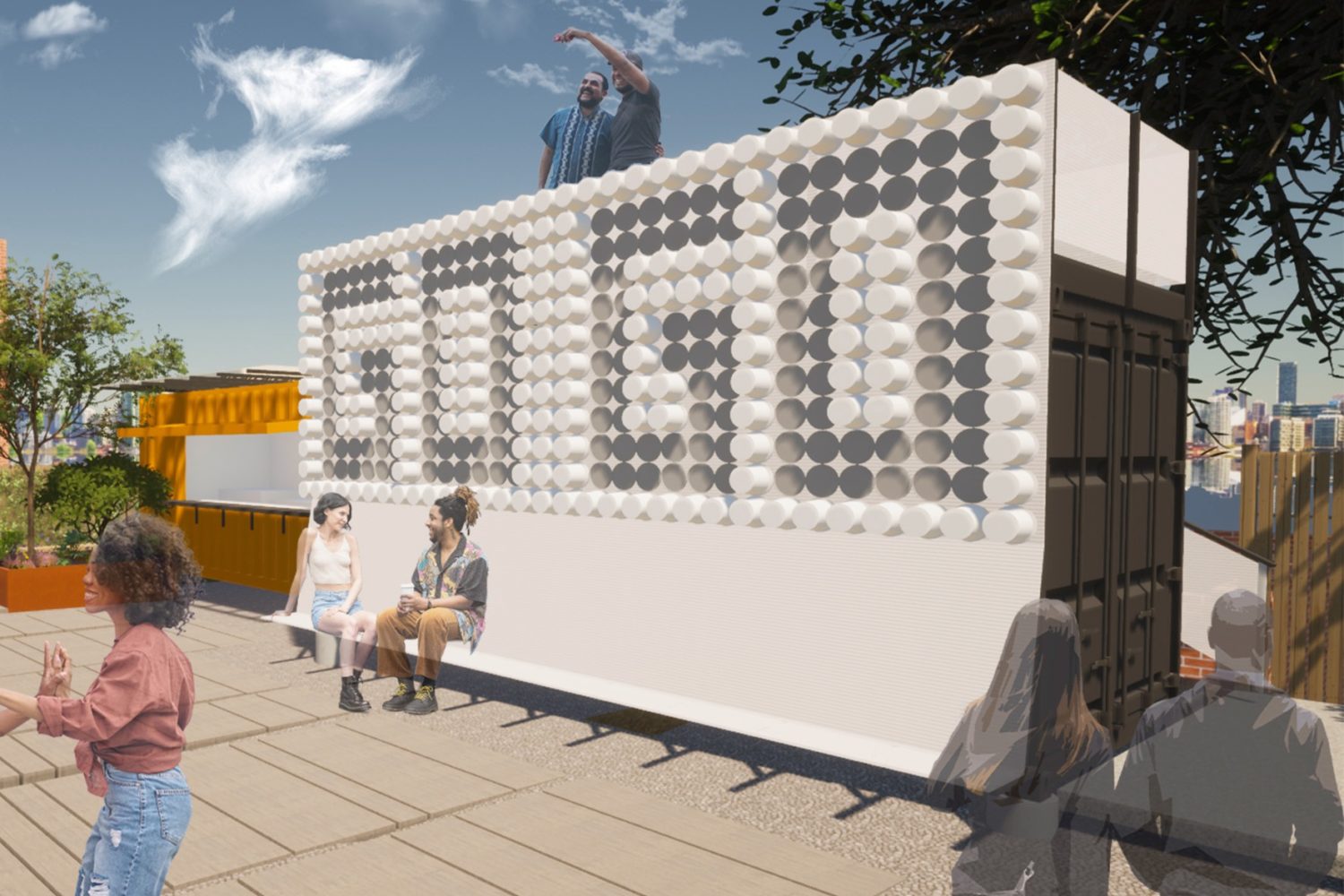

Less than a week ago, Washington’s network of attractions added a new destination when the Lillian and Albert Small Capital Jewish Museum opened its doors to the public. Located at F and 3rd Streets NW, the museum is comprised of a historic 19th Century synagogue—which was picked up and moved one block to its current location—as well as a new building featuring three floors of exhibition galleries.

Describing itself as “the first museum in DC dedicated to the story of Jewish life in the nation’s capital region,” the Capital Jewish Museum’s collection includes everything from a matchbox bearing Jimmy Carter’s signature that was used in 1977 to light the first-ever National Menorah to a sign from the now-shuttered Bethesda Bagels location in Dupont Circle.

To learn more about how the museum came to be and what visitors can expect, Washingtonian spoke with executive director Ivy L. Barsky. The following been edited for space and clarity:

How did the museum initiative get started?

The Jewish Historical Society of Greater Washington was founded by volunteers in the 1960s, so the precursor to our institution goes back to the 1960s. In 1965, that [organization] became a nonprofit. And the real motivation happened in 1969, when the historic synagogue from 1876 needed to be moved. WMATA headquarters was going to displace it, and they were going to tear down the synagogue. And this group of folks from the Jewish Historical Society of Greater Washington decided they couldn’t let that happen. They organized to save the building, get it landmark status, raise money for it, and physically move it.

Later, in the 21st Century, the leadership started thinking about trying to tell a bigger story, realizing that we were the only major region with a Jewish population that didn’t have a Jewish museum. In the twenty-teens, those discussions really solidified, [along with] the intent to make a bigger project happen. So 2017-2018 was around the time when we were making the transition from a historical society to a museum. And because Albert Small had been involved and cared deeply about this project and had a vision for it, in 2018, we announced the new name, the Lillian and Albert Small Capital Jewish Museum, and [we] started to do feasibility [studies], get architects, all of that.

What was the vision for the museum?

Documenting and really exploring the history of Jewish Washington and the region, which is really different from the stories [of other] Jewish communities in the United States. So telling that story. And then I think our kind of unique vision and value proposition was: connect, reflect, act. You know, building a museum in the 2020s, we can’t just do it the old way. I think there has to be a new consideration of what our story was going to mean. And so it’s about connecting the communities—individually and across generations. Reflecting on what history means for today. And then thinking about how to act to make the world a better place, based on what we have to say and [rooting] some of that in Jewish values.

So how are those three pillars—connect, reflect, act—manifested in the museum?

It’s hard to parse them all out because it’s all part of the experience of being in the museum, and of course, everyone comes in with their own context and their own history. So there are some people who were connecting, for example, because they’re fourth-generation Washingtonians and they recognize their family and friends in the exhibition. But I think there are lots of ways for different folks to connect to the exhibition.

Then we reflect on what history means for today. A really good example of that is our Seder table. We have an interactive Seder table that looks at the story of Passover and stories of liberation and freedom. But in that part of the exhibition, we look at the Freedom Seder from 1969, an interfaith Seder between Blacks and Jews. They came together a year after MLK’s assassination to look at, How do we look at the story of Passover through the state of our country right now? And what do we do moving forward?

And then “act” is a really important piece of what we do. So we have six what we call pods in [one] section of the exhibition, and we have six topics, [such as] voters’ rights, reproductive rights, immigration, and antisemitism. And for each of those themes, we look at, What does Jewish wisdom and Jewish texts say about this issue? What does American law say about this? Who are the people or individuals working on this topic? And then, What can I do? What am I interested in? And what might the museum prompt me to think more about or to do as I leave?

And after you leave the core exhibition—connect, reflect, act—[you can] go into our Community Action Lab, which, as we like to say, turns inspiration into action. So that’s the place where if you care about voting rights, here’s where you can check to make sure you’re registered to vote. If you’re not, you can register. Or you can learn what the newest legislation or conversations are around DC statehood around voters’ rights. So that’s where we hope that some of that inspiration from the core exhibition turns into action.

Among other things, the museum has on display a number of signs from now-defunct Jewish-owned businesses in the Washington area, such as Abe’s Jewish Books. How did the museum go about collecting these items?

There was a lot that was collected over the years through the Jewish Historical Society of Greater Washington: minutes from synagogue board meetings from various synagogues around town, sermons from different pulpits, things from businesses, and obviously photographs. But right now, our curator of collections, Jonathan Edelman, is actively collecting. So for example, when he knew the Bethesda Bagels was closing in DuPont Circle, he asked to get that sign. Some [items] have been in the collections for a long time. Others have been [obtained by] either people coming to us and saying, “Do you want this?” or us going to them and saying, “Can we have it?” So I would say that the stories of how things were collected for our collection are as varied as the collections themselves.

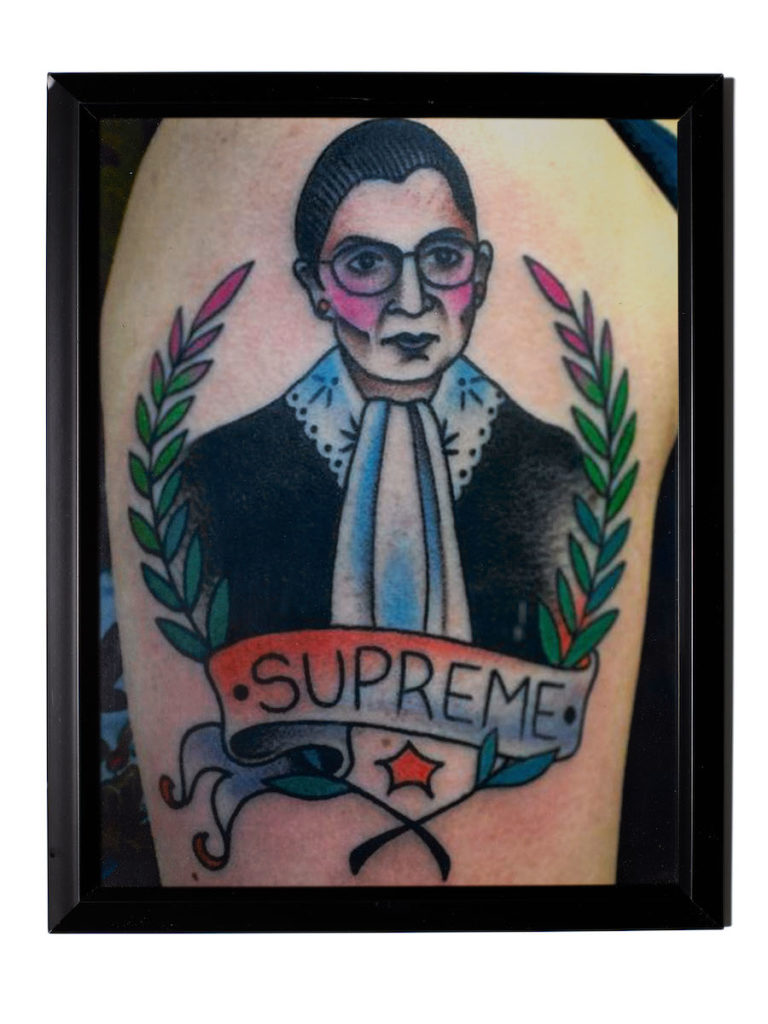

Can you tell me about the Ruth Bader Ginsburg exhibition?

So the “Notorious RBG: The Life and Times of Ruth Bader Ginsburg” [exhibit] was organized and circulated by the Skirball Cultural Center in LA. It’s had many stops across the country, including the New York Historical Society in New York. And we will be the last stop for this exhibition, appropriately since this is where RBG’s life and work took their last breath. But also the fun stuff, like the pieces from [RBG’s husband Marty Ginsburg’s] kitchen. We have a whisk and mortar and pestle of his borrowed from the Supreme Court archives. The exhibition really started in LA by the authors of the Notorious RBG book, which grew out of a blog. So it deals with her as a pop culture icon, but also has some substantive content [presented] in a very digestible way.

What’s the response been like so far from people who have visited the museum?

Well, I have to say, I think we’re kind of blown away by the feedback we’ve gotten so far. I think people who knew about us in the past think of us as a small place. They think of us as the footprint of the synagogue. But we’re actually a beautiful, airy, light-filled, 32,000-square-foot building. And so I think people are surprised by the ambition and the complexity and depth of the exhibitions. We’ve gotten fabulous feedback from all kinds of people. We’re very, very encouraged by the initial responses.

![Luke 008[2]-1 - Washingtonian](https://www.washingtonian.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Luke-0082-1-e1509126354184.jpg)