Contents

If you live in Washington, you likely know the Watergate from driving along Rock Creek Parkway or Virginia Avenue, where its spherical concrete facade curves with balconies that look like rows of jagged teeth. If you don’t live here, you probably know it as simply a synonym for scandal: the site of the 1972 Democratic National Committee headquarters break-in, which ultimately led to President Richard Nixon’s resignation.

For decades, however, many Washingtonians have simply known the Watergate as home—albeit one with a storied history, having housed perhaps the highest concentration of accomplished DC people in one place.

Sue Greenberg, who has lived in the complex since 1966, has stories of her own—such as the time she learned how to put ice cream in eggnog from John Duncan, the District’s first Black commissioner and a JFK appointee. (Prior to 1967, a three-member, federally appointed board of commissioners governed the city.) One Halloween, the 82-year-old says, her trick-or-treating children arrived at the door of a Watergate resident who also was a public figure. (Alas, Greenberg won’t name names.) The woman was having a dinner party, and she put only pennies in their UNICEF donation boxes. “My son, who still has a very big voice, said, ‘That lady must be very poor!’ ” in front of the whole dinner party, Greenberg says. During Nixon’s presidency, Greenberg lived down the hall from attorney general and campaign chairman John Mitchell and his wife, Martha, whose custom of calling reporters with gossip earned her the moniker “Mouth of the South.” Greenberg recalls the couple’s habit of leaving a coat rack for guests outside their door when they entertained. Following the infamous break-in, Greenberg found her children standing outside the complex, offering apartment tours for $5. “Till I caught ’em,” she says.

A ten-acre site stretching along the Potomac, the Watergate contains six structures: three residential co-ops, two office buildings, and an eponymous hotel. When the first residential building opened in 1965, people were abandoning cities for suburbs, so the design goals were safety and convenience—“a city within a city,” says Joseph Rodota, author of The Watergate: Inside America’s Most Infamous Address. The result was the city’s first mixed-use development. It had a Safeway, a pharmacy, a bakery, a post office, a liquor store, a florist, a beauty salon—everything you could want. “This was really quite a novel concept,” Rodota says.

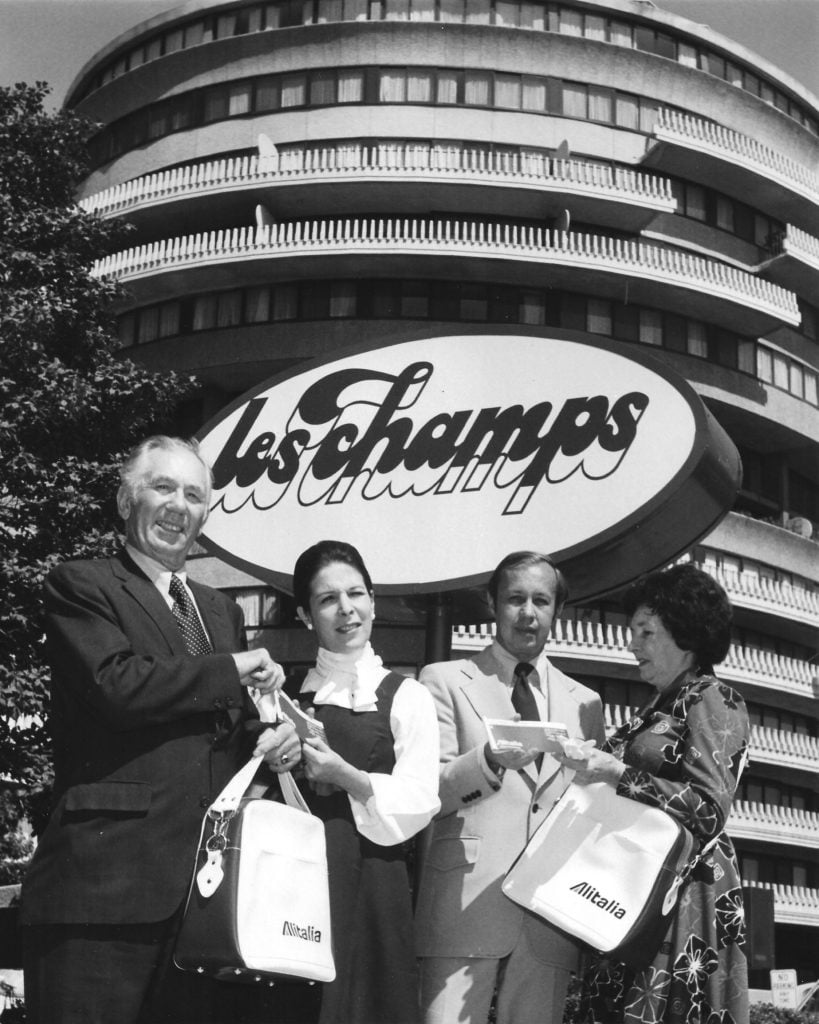

It was also billed as the height of luxury. “Watergate is unquestionably Washington’s most elegant, most exciting, most sought-after new address,” reads a 1966 brochure for potential buyers. The complex had multiple pools, restaurants providing residential room service, heated garages, 24-hour reception, and a health club. Some units even came with maids’ quarters. Eventually, a high-end shopping area called Les Champs opened, featuring such stores as Yves Saint Laurent, Gucci, and Valentino, along with the chichi restaurant Jean-Louis, which brought French nouvelle cuisine to Washington. The aesthetic was modern and statementmaking, created and designed by an Italian development group and architect. “Italy was as cool as it can be in the ’60s,” says Rodota, referencing touchstones like designer Oleg Cassini dressing Jackie Kennedy and actress Sophia Loren’s stardom. “To have this avant-garde Italian building land in Washington was really quite extraordinary.”

In 1966, efficiencies started at $16,400 and penthouses at $189,700, allowing the Watergate to reach a range of buyers. (Rodota says it was especially popular among the growing sector of young, unmarried working women looking to buy.) However, it quickly became known as a spot for local glitterati. “In Washington it used to be Georgetown—now it’s Watergate,” reads a 1969 Life article. “Just everybody lives there.” In the Nixon era, “everyone” included the President’s secretary Rose Mary Woods and renowned Washington hostess Anna Chennault. In the 1980s, President Ronald Reagan’s friends, cabinet officials, and other administration insiders flocked to the residences and hotel—and hung out at Jean-Louis, where the President had an after-party for his 70th birthday and was serenaded by Jimmy Stewart.

While the Watergate housed many big names, it was also a place where bigwigs wanted to eat dinner, watch TV, and clip their toenails just like everyone else. “Now you look back on it and it sort of seems iconic,” says journalist and DC fixture Sally Quinn, who lived there for a period starting in 1973 with her then boyfriend, Washington Post executive editor Ben Bradlee. “But you didn’t think of it that way at the time. You were living your life.” Of course, Quinn also tells a story about when she and Bradlee encountered fellow resident Senator Bob Dole and CBS’s Lesley Stahl—who Quinn says were then dating—in the lobby. This was before Nixon’s resignation, when Dole was still defending the President and railing against the Post for its coverage. Despite their differences, Bradlee and Dole slapped each other on the back and said hi, Quinn remembers. Not your typical apartment encounter.

The Watergate has seen its share of issues, too. Activists were arrested outside it during a 1970 protest after the sentencing of some of the Chicago Seven. (The complex was chosen because it represented “the ruling class,” according to Rodota’s book.) At times, residents have complained about water damage, defective plumbing, and air-conditioning malfunctions, leading to some lawsuits; board and resident kerfuffles have arisen; and, during 2015 construction on the hotel, part of the parking garage collapsed and injured two people.

Over the years, the Watergate has lost some of its grandeur: Jean-Louis closed, as did the CVS and Safeway (dubbed the “Senior Safeway’’ for its appeal to an older clientele). Ownership of the buildings has changed, and the retail area is mostly empty. Today’s local VIPs are more likely to buy into developments like the Wharf’s high-end Amaris. Still, the Watergate has an iconic place in local and national history, and continues to house Washingtonians with impressive résumés, though more under-the-radar ones. As Quinn puts it: “There’s nobody in the world who is educated who doesn’t know about Watergate.”

MEET THE RESIDENTS

Portraits by Lexey Swall

Jean Efron

Rubbing shoulders—and paws—with Washington’s elite

“It was love at first sight when I walked in the door,” Jean Efron says of her Watergate West apartment, which she purchased in 2007 after originally buying a Watergate East unit in 1987. Over the years, the art adviser, who is in her seventies, has had her share of experiences—sometimes spotting celebrities emerging from limousines, other times having more prosaic encounters. She ran into Martin Ginsburg, Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s husband, shopping at the Watergate’s Safeway, crossed paths with political consultant Roger Stone while walking her dog, and saw former cabinet secretary Elaine Chao at the Watergate salon. Once, when Efron was there getting a manicure, “this voice next to me said, ‘Oh, you have nice nails.’ And it was Condoleezza Rice.”

Thanks to a mutual love of dogs, Efron became friendly with Senator Elizabeth Dole and her late husband, Senator Bob Dole. “[Bob] could talk about dogs and come to tears because he just loved them so much,” Efron says. Well-known schnauzer aficionados, the Doles used to throw birthday parties for their dogs in their Watergate home. Efron once attended one, bringing her dog at the time, a West Highland white terrier named Jelly.

Efron didn’t typically allow her dogs on the furniture. That had to be off-limits at the home of one of DC’s most powerful couples, too, right? Guess again. “Here I am in this gorgeous apartment belonging to Senators Dole,” Efron says, recalling that the dogs hopped right up onto the couch—a much better position for the pets to eat the birthday cake Elizabeth served them. “It was a scream,” Efron says.

Back to Top

George and Wati Alvarez-Correa

Receiving a neighborly apology note like no other

George Alvarez-Correa paid $155,000 in 1979 for his one-bedroom Watergate South unit with a balcony overlooking the Potomac. This was right before the complex became unofficial HQ for “The Group,” a crew of glamorous Reagan insiders that included Leonore Annenberg, a chief of protocol for Ronald Reagan; her husband, publisher Walter Annenberg; and Bloomingdale’s heir Alfred Bloomingdale.

When George met his now-wife, Wati, in 1986, she was initially reluctant about the whole thing. “I was like, ‘I’m not going to date somebody who lives in the Watergate, with these crystal chandeliers and women walking around in their fur coats,’ ” she says. “It really had that reputation back then.”

Today, the retired couple—George, 75, worked in investment management; Wati, 66, once worked at Washingtonian—live in McLean full-time but still maintain their Watergate spot. After President Bill Clinton’s affair with White House intern Monica Lewinsky became the national story in the late 1990s, Lewinsky was living in her mother’s Watergate South apartment. Paparazzi and news vans camped outside 24-7, essentially putting Lewinsky on house arrest. (Senator Bob Dole lived next to her at the time, and he reportedly sent doughnuts to the photogs.) Wati remembers Lewinsky as nothing but gracious—before moving, Lewinsky sent a note to all the building residents on Tiffany-blue stationery apologizing for the spectacle. “It must have leaked out, because somebody wrote us offering to buy the letter,” Wati says. (They declined.)

Meanwhile, George used to see Ruth Bader Ginsburg at the pool, always wearing a blue one-piece bathing suit. He recalls that the Supreme Court justice would tiptoe to the edge of the diving board, then stand there as if working up the nerve to jump off. “When she finally dove in, she did it very nicely, with good form,” George says. “No splash.”

Back to Top

Gigi, Colette, and Danielle Winston

Making three generations of Watergate memories

Gigi and Colette Winston have spent most of their lives at the Watergate. Their father, Henry Winston, became the complex’s manager in 1968, a position he occupied for almost two decades, and their mother, Tina Winston, ran three stores at the complex with her sister, most notably a women’s clothing store, Colette of the Watergate, on the ground floor. The sisters and their parents, grandmother, and aunt all eventually lived in the Watergate at the same time, and Colette’s daughter, Danielle Winston, was born and raised there. “She was Eloise at the Plaza,” Colette says. Today Gigi (“I never tell my age”), Colette, 70, and Danielle, 34, all work at the family’s company, Winston Real Estate, which handles many of the Watergate’s sales.

Colette remembers her father getting on the loudspeaker at the complex’s shopping mall and pulling pranks, such as asking for Robert Redford to come to the front office. “Of course, that caused a furor,” she says. Not that there was a shortage of celebrity sightings. Take the time comedian Phyllis Diller lost her luggage before a Kennedy Center performance, as Colette recalls, and Tina had to open the store after hours to help her find an outfit. (Sadly, the shop didn’t carry shoes, so Diller had to perform onstage in outfit-clashing boots.) Or the time a man Tina didn’t recognize came into the store with an entourage of bodyguards. She asked one who the guy was—Prince, he told her. “And my mother says, ‘Prince of what?,’ ” says Colette. Or the time the sisters ran into Lucille Ball in the Watergate Hotel’s lobby and invited her to a family dinner. Ball had to pass—she had plans with Bob Hope. “It was very common to stand at the hotel and have a movie star next to you waiting for a cab,” Gigi says.

That wasn’t all: Plácido Domingo would hum on the elevators (“You felt like you were getting a show,” Gigi says), and the sisters shared a trainer with Condoleezza Rice (or, as she told Colette, “Call me Condi”). Gigi says Rice had two Watergate units—one for living, the other for her gym and guests. And Danielle became buddies with longtime Watergate South resident Ruth Bader Ginsburg—in fact, the Supreme Court justice wrote her law-school recommendation letter. According to Danielle, she also was once one of Ginsburg’s two Facebook friends. (The other was her granddaughter.)

Then there’s the door. As the Winstons tell it, the FBI asked their father to hold onto one of the doors leading to the Watergate offices Nixon’s accomplices had broken into. It was covered in FBI signage, they recall, and there was tape over the lock. Henry put it in a storeroom, but the FBI never returned for it. So it became something of a party trick: “Every time we had company, [Dad] would say, ‘Wanna see something really cool?’ ’’ says Colette. “And he’d bring them down to the storeroom to see the door.” One day, the door went missing—the family thinks a building engineer stole and sold it. Years later, Colette says, she spotted it at a Newseum exhibit: “I exclaimed, ‘That’s our door!,’ and everyone turned around to look at me like, Is she crazy?”

Back to Top

Fred and Jill Schwartz

State secrets, dress dilemmas, and some very unique homework help

“Every scandal worth its salt has our name attached to it: The such-and-such gate or the so-and-so gate,” says attorney Fred Schwartz, an 80-year-old who has lived in the same Watergate West unit since 1978.

While many of the complex’s longtime residents “have two or three notches under their belt,” he says, most tend to be fairly humble, despite their stacked résumés—Washington fame can be nerdy and niche, a far cry from the TikTok-documented and bedazzled celebrity of LA or Miami. “The only way you find out [their significance] is if they run for the board or they die,” he says.

Living at the Watergate has its perks. Once, Schwartz recalls, a neighbor who happened to be a CIA agent declassified documents on the Hindenburg dirigible disaster for Schwartz’s daughter’s school project. It also creates unique dilemmas: His wife, Jill Nevius Schwartz, 76, once arrived at one of the complex’s front desks with a friend, who noticed that another resident’s tag was sticking out of her dress. The two spent several minutes debating before deciding they just couldn’t tuck it in for her because, well, it was RBG.

Thanks to their rescue pup, Sasha, Fred and Jill are big on the Watergate dog circuit. Several years ago, Fred was on the same nightly dog-walking schedule as Robert McFarlane, President Reagan’s national-security adviser and a key figure in the Iran-contra scandal. “[He] was absolutely the kindest person,” Fred says. “So I felt an obligation to tell him none of us are perfect. And then he rewarded me by telling me secrets.” What kind? Fred won’t spill specifics, but it had something to do with “Star Wars”—Reagan’s Strategic Defense Initiative, not Yoda and C-3PO. “I keep wondering whether someday somebody’s going to knock at my door,” he says, “and say I’ve committed a crime by finding [this] out.”

Back to Top

George Arnstein

Witnessing history at home—and by the pool

George Arnstein, 98, and his late wife, Sherry, were two of the first people to live at the Watergate, having bought their original unit in 1965 based on plans and models. They decided to move there, Arnstein says, in part because they didn’t agree with the racist policy at their Arlington apartment that barred Black people from the pool.

Arnstein worked in higher education and his wife in healthcare policy—at one point, she focused on desegregating American hospitals. When they moved in, Arnstein says, one resident was so enamored with the Watergate’s luxurious reputation as to request that the doormen wear tails. (That didn’t happen.) Arnstein also remembers Vice President Hubert Humphrey touring the complex before deciding to live elsewhere—he likely would have needed to keep an entire elevator to himself for security reasons, Arnstein says, and the board wasn’t having that.

The couple lived at the Watergate during the infamous 1972 break-in. “I slept through it,” Arnstein says. “And so, like everybody else, I saw pictures on TV in the morning.” The liquor store in the downstairs shopping mall was “quick to capitalize on this,” he adds, recalling that its owner swapped out bottle labels to advertise them as “Watergate Vodka” and appeal to the nation’s growing fixation. Several Nixon officials were also residents, and one day during the on-going political crisis, Arnstein went to sit by the pool. When he returned, his wife asked who else had been there. “I said, ‘Oh, there weren’t very many [people], only three or four,’ ” he recalls. “ ‘I think I was the only one not under indictment.’ ”

This article appears in the June 2023 issue of Washingtonian.