One February night in 1927, somebody smashed Daisy Welling over the head with a brick as she walked across the grounds of the Capitol, on her way home from her job as a telephone operator at the nearby Hotel Driscoll. Her skull was fractured, and the attacker pulled her into the bushes, raped and robbed her, then ran off. Welling survived and was able to give a vague description of her assailant. The ensuing response was “one of the most intensive man hunts in the history of the city,” as a newspaper columnist put it.

Police quickly rounded up an assortment of men who fit Welling’s imprecise description of a light-skinned Black man around 30 years old. One of them, Philip Jackson, eventually confessed to the crime, and the case was considered solved. Jackson later recanted that admission, though, insisting it had come only after two days of violent questioning by the cops. He also had an alibi that, while not airtight, was corroborated by two witnesses.

Jackson’s trial was brief, and the evidence—at least as chronicled in newspaper reports at the time—now hardly seems definitive. Yet it took just an hour for the jury to convict him of “criminal assault” (as rape was euphemistically called). Their recommended punishment was death; at the time, rape was a potential capital offense in the District.

Jackson’s attorney appealed the death verdict. Among other things, Jackson—whose parents were said to be a brother and sister—was described as being of unsound mind. But those efforts proved unsuccessful, and President Coolidge rejected a final appeal for clemency.

On the morning of May 29, 1928, three guards led Jackson down a long corridor on the fourth floor of the District jail. Their destination was a straight-backed wooden seat, illuminated by a beam of sunlight shining in through the jail bars: Washington’s new electric chair. Jackson was about to be the first person killed by it.

A reverend accompanied Jackson on this final walk, reciting the Lord’s Prayer and the 23rd Psalm: “Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, I will fear no evil . . . .” Jackson, repeating the words, turned around and lowered himself into the chair. He continued praying even as his voice was muffled by the leather mask fitted over his face. Shortly after 10 AM, with Jackson now strapped in place, the executioner gripped the handle on the control panel and pulled.

On a recent Tuesday morning–95 years and around 50 executions later—I wrapped my own hand around that same lever and gave it an uncertain tug. Nothing happened: The chair is no longer connected to an electrical source, and the handle is now locked in place. But recreating that terrible act was intensely creepy in a way I wasn’t quite prepared for—a grim link not just to the scores of people who expired in this oddly unimposing piece of furniture but to the victims of the crimes they were convicted of. Decades of brutality and horror were directly connected to the short lever that my fingers now curled around. I couldn’t let go fast enough.

The District’s electric chair isn’t in a museum, and the public isn’t generally invited to see it. Instead, it’s kept behind a locked door marked “Microfilm Storage” in a windowless room at the DC Archives building in Shaw. No effort has been made to present it: You walk through the door and there it just sits, unceremoniously wedged between a filing cabinet and some boxes of old documents.

At a glance, it resembles an old-fashioned shoeshine chair. But then you notice the belt restraints, the blindfold, the electrode-fitted headpiece that provided the jolt—all still right there, as if the thing could be plugged in and fired up tomorrow. “It’s a piece of the city’s history—and, of course, America’s history,” said DC archivist Bill Branch, who had agreed to show it to me. “Things like this, I think they need to be kept and dis-played to remind us where we were—and that we don’t want to go back.”

Before my visit, I had been contemplating the unpleasant question of whether I would, if the opportunity arose, sit in the chair myself. I asked Branch if he’d ever done it. “I think that could be sacrilegious,” he said, recoiling slightly. “After 50-some people died in that chair, I honor their presence. It’s like going to a cemetery.” It seemed unwise to ask if I could give it a try.

Jackson didn’t die after the first wave of electricity ripped through his body. As he lay slumped over, the prison doctor listened with his stethoscope, then shook his head: Jackson was still breathing. The process was repeated, but again he lived, and he survived another try after that. In the end, it took six attempts before the doctor finally declared him dead. One witness that morning was John Roberts, an evangelist who had previously been on hand for 57 hangings and was witnessing his first electrocution. He told the Washington Post that “it was the most horrible death he had ever seen a man die.”

The electric chair had been intended as a more humane execution method than hanging, a technological advance that Thomas Edison himself had been involved in developing in the late 19th century. But from the start, botched electrocutions were common, and even when things went as planned, the harsh reality of death by electricity tended to rattle spectators. That didn’t prevent a series of states from adopting it as their primary mode of execution, beginning with New York in 1888.

It took a while for the idea to gain currency in Washington. In 1911, the Post reported on growing opposition to hanging, with “talk of the electric chair” in the air as a replacement. (Back then, capital punishment was mandatory for first-degree murder convictions in DC.) A former warden of the District jail warned that he considered the electric chair “torture,” but pro-death-chair voices kept getting louder, pushing the idea that electrical executions were less cruel. Finally, in 1925, Congress passed a bill making the electric chair Washington’s official method. The old gallows inside the District jail—which had been used to hang the man who assassinated President Garfield, among many others—would be scrapped.

Congress appropriated money for the District to purchase a chair, but apparently such devices weren’t available simply to order from a death-chair catalog; it would have to be built from scratch. The city’s chief electrical engineer, W.B. Hadley, was dispatched to Sing Sing prison in New York, home to one of the country’s most notorious electric chairs. Hadley spent most of his time on projects like upgrading the city’s network of streetlights. Now there he was studying the electrical specifications that could deliver fatal voltage to a human being.

The process—presumably as determined by Hadley on his trip—would at some point be written in red ink on a three-by-five card, as the Post later reported. “Pull the wooden handle—labeled main switch—spin the control wheel to the right, and keep your eye on the voltage meter. For the first 6 seconds, give 2,000 volts, followed by 50 seconds of 500 volts. Then, 3 seconds of 1,000 volts, 50 seconds of 500 volts, and, finally, 6 seconds of 2,000 volts. Total elapsed time: slightly less than 2 minutes.”

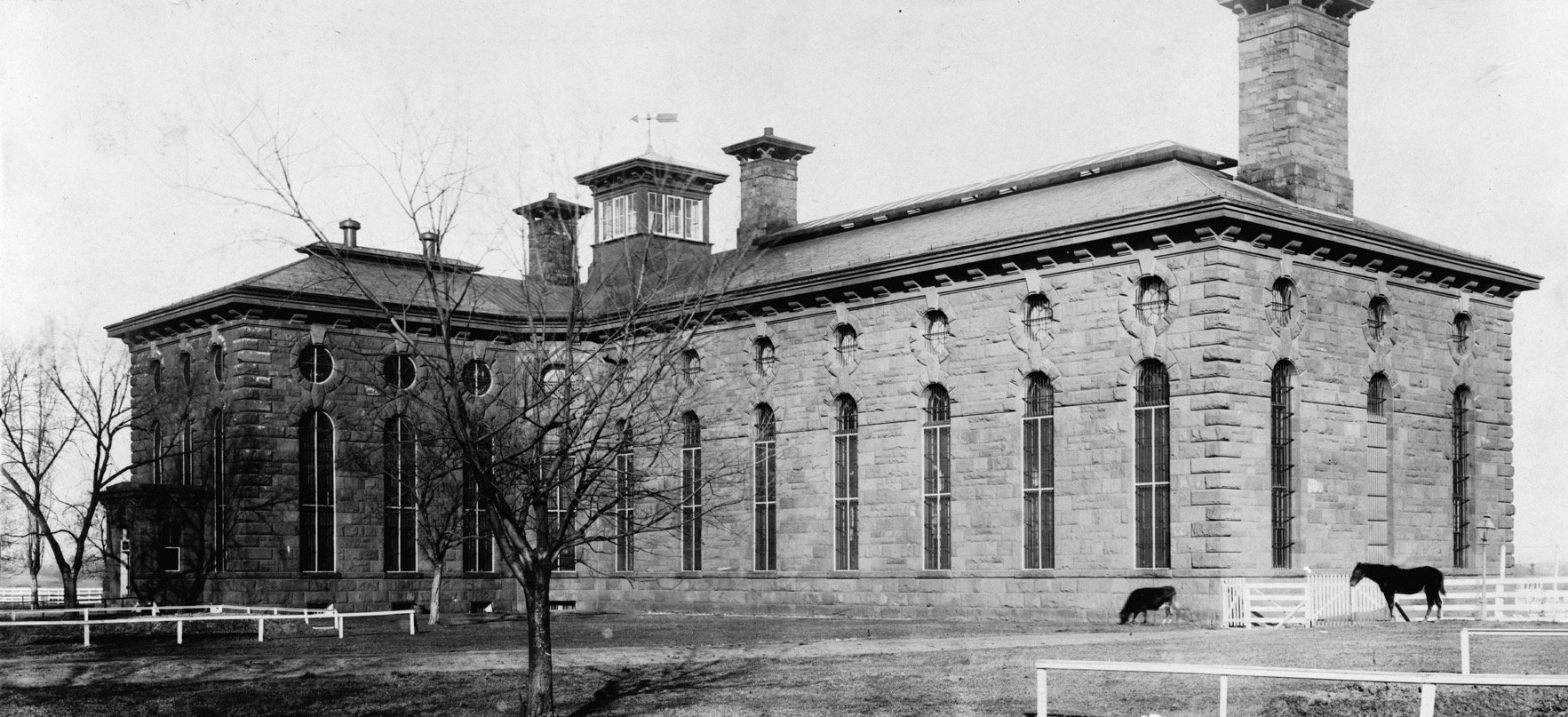

The chair was apparently constructed by workers at the District repair shop on U Street, Northwest, then taken to the Washington Asylum and Jail, as it was officially called. The jail was a forbidding stone structure built (though not designed) by Adolf Cluss, the architect responsible for local landmarks such as the Smithsonian Arts and Industries Building and Eastern Market. Opened in the 1870s, it was located near Congressional Cemetery in Southeast, adjacent to the site of DC’s current jail.

In the early days, whenever the time came for the chair to conduct its deadly business, it would be dusted off and set up at one end of the prison dining hall. Executions were scheduled for right after breakfast. Once the deed was done and the body removed, the chair would go right back into storage—just in time for prisoners to file in for lunch.

Over the next three decades, dozens of people were executed in DC’s chair. Who were they? Reading through the long list is a depressing exercise: Rapists of children. Murderers of wives and girlfriends. Killers of shop clerks and cops and taxi drivers. The most famous of the city’s electric-chair executions came in 1942, when six Nazi saboteurs were put to death at the District jail. Sent by the Germans to attack targets inside the US, they had arrived via German submarines, carrying large amounts of explosives. But before they could blow anything up, a member of the group got cold feet, took a train to DC, and confessed the whole thing to the FBI. The would-be saboteurs were quickly apprehended and tried by a military tribunal, a controversial decision directed by President Roosevelt himself and upheld by the Supreme Court. On August 8, 1942, four days after being found guilty, six of the Germans were electrocuted in quick succession at the jail. It took just over an hour.

Another case that made national news in the 1940s was the serial killer Jarvis Theodore Roosevelt Catoe, who confessed to raping and choking to death a series of women in various locations near Dupont Circle, as well as other brutal crimes (though he later recanted the confessions). Catoe’s capture was covered by Time and the New York Times, along with more sensationalistic outlets: The pulp magazine Actual Detective Stories promised, for the price of 15 cents, the inside story of Catoe’s “brutal, insensate reign of terror.” After the former undertaker’s assistant was arrested in 1941 and tried for one of the killings, a panel of Washingtonians wasted no time in deciding his fate. “Catoe Doomed By Jury In 18 Minutes,” read the huge headline in the Evening Star.

On the morning of January 15, 1943, Catoe was escorted to the chair that would soon take his life. As he was strapped in, he quietly sang the hymn “Precious Lord Take My Hand.” A handful of newspaper reporters watched through one-way glass as the switch was pulled. Five minutes later, he was pronounced dead. “The execution closed a sensational career of murder,” the Star wrote, though “police probably never learned the full extent of Catoe’s criminal activities.”

The chair would be set up at one end of the prison dining hall. Once the deed was done, it would go back into storage, just in time for lunch.

In 1946, three men were executed in the chair within hours of one another on the same day. Julius Fisher had been a janitor at the National Cathedral; he confessed to murdering the cathedral’s assistant librarian after she complained to his supervisor that he hadn’t swept properly under her desk. Fisher split her skull with a stick of firewood and strangled her, then stashed the body in the library’s subbasement. William Copeland, meanwhile, had been convicted of shooting and killing his sister-in-law. As he made the final walk to the chair, he was allowed to smoke a cigar, a “faint smile on his lips as he entered the death chamber,” according to one account. He took one final puff, then submitted to the 2,000 volts.

But it was the third man, Joseph Medley, who attracted most of the attention that day. Condemned for shooting a woman in a robbery after an all-night poker game at her apartment at 16th Street and Florida Avenue, he had previously escaped from prison in Michigan and was suspected of killing two other women in New Orleans and Chicago. (All three victims reportedly had red hair.)

Following his conviction, the “suave slayer,” as the Post described him, became even more notorious for staging an escape from death row at the District jail. He and another inmate overpowered two guards with whom they’d been playing cards, then fled to the roof through a ventilator shaft and dropped to the ground using bed sheets. Fisher and Copeland, offered the chance to flee death row as well, refused and stayed in their cells. Medley was caught hours later, “wet and bedraggled,” in a sewer pipe near the Anacostia River. “You can’t blame a fellow for trying,” he told police, according to the Star. He found religion in jail; his final moments were spent clutching a rosary in his right hand. The Post’s banner headline ran across the top of page 1: “Killer Medley Dies With Prayer on Lips.”

The death penalty was effectively nullified in DC by a 1972 Supreme Court decision, but it wasn’t officially repealed by the DC Council until 1981. By that point, the electric chair hadn’t been called on for almost 25 years. The last person to die in it was Robert Carter, convicted of killing a police officer and executed at the jail in 1957. Five years later, Congress passed a law eliminating mandatory executions for first-degree murder convictions in DC, and the penalty was never again imposed.

But while the capital punishment didn’t survive here, the electric chair did. It was kept for years in the old DC jail building, then eventually made its way to Lorton, the Virginia penal complex that was once part of the DC corrections system. (It was never actually put to use there.) After Lorton was shuttered in 2001, the DC Archives came and collected a trove of material, including the chair.

Since then, the device has been stashed inside the converted 1883 horse barn that houses much of the DC Archives’ collection. Few people are ever able to see it, in part because the cramped and uninviting building—tucked away in an alley near the convention center—is more of a storage complex than a modern facility serving researchers and the community. “We have to almost discourage people from physically coming into the archives—we don’t have the capacity,” says state archivist and public-records administrator Lopez Matthews Jr., who oversees the DC Archives. The building ran out of space in the 1990s; many records are now stored elsewhere.

That’s why an effort is underway to construct a badly needed new archives building on UDC’s Van Ness campus. The $104 million project, which has already been mostly designed and is planned for a 2026 opening, would be the kind of sleek space that you’d probably assume—incorrectly—already houses the city’s important records (things like birth and death certificates, along with historically significant documents dating back to the 18th century). On top of everything else, the current setup has no special temperature or humidity controls, putting these vital papers at risk.

If the building proceeds as planned, the new archives will include plenty of room for exhibits, something the current facility doesn’t have space for. And that, finally, should provide opportunities for the public to come see the electric chair. Though it likely won’t be on permanent display—“It’s a bit morbid,” Matthews says—it would be brought out as part of relevant exhibitions, such as a history of Washington’s penal system.

Yet Matthews cautions the curious that being in its presence is an experience not easily shaken. When asked if he has ever pulled the handle or even taken a seat, he lets out an uneasy laugh: “Absolutely not. I have not physically touched the chair.” But he certainly has contemplated its history. “It does kind of stick in your mind that [people were] actually killed here,” he says. And he has no doubt the chair is worth preserving. “It’s an example of how we have evolved in terms of our treatment of those who are incarcerated,” he says. “This is the brutality of the past. You know, you can read it in a book, you can read it in the paper, but to actually see a physical relic of that time gives you a different feeling. You understand it better. You’re like, wow, this was real. It makes it real.”

This article appears in the November 2023 issue of Washingtonian.