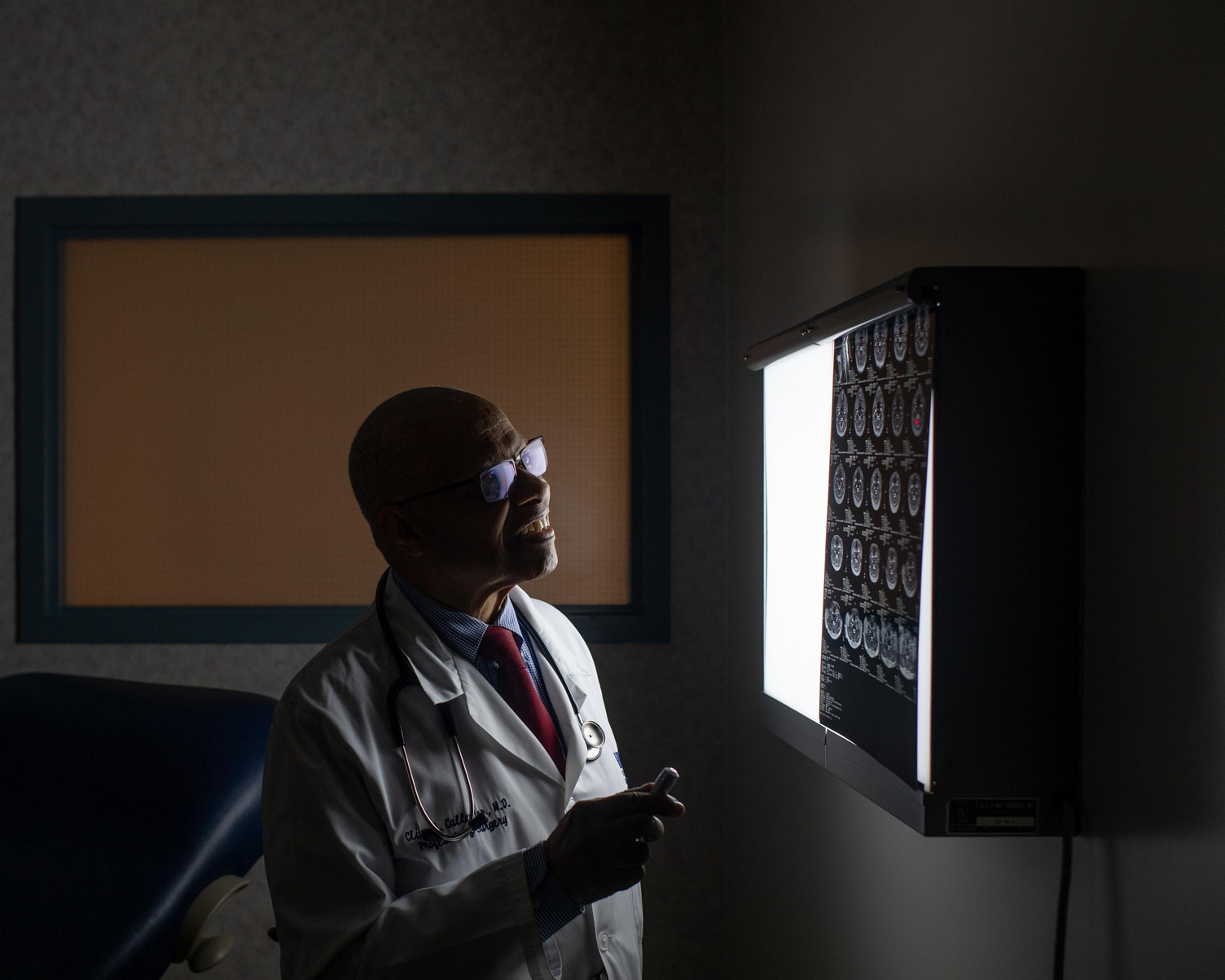

People of color make up almost two-thirds of the national organ-transplant waiting list, yet they’re less likely to receive organs than their white counterparts. Dr. Clive O. Callender, a pioneer in transplant medicine, has spent a lifetime trying to improve their odds. In the early ’70s, the Howard University Hospital surgeon and professor opened the country’s first minoritydirected dialysis and transplant center. When he noticed that an overwhelming majority of organs received at the center, which served mostly Black patients, came from white donors, he started the National Minority Organ/Tissue Transplant Education Program. (Though organs aren’t matched to patients based on race or ethnicity, those of the same background are likelier to have compatible blood and tissue types.) Callender’s team traveled across the US speaking with minority communities to demystify the donation process and encourage participation. His efforts succeeded: Donation rates among Black Americans have more than tripled over the past 30 years. Practicing medicine has been a dream of Callender’s since he was seven—one that almost didn’t come to fruition after he was hospitalized with a life-threatening illness as a teen. Now 87, he reflects on his journey.

“When I was 15, I contracted pulmonary tuberculosis and had to get half of my right lung removed. I had been in the hospital 18 months, and my uncle brought me The American College Dictionary and the Merck Manual—the doctor’s Bible. I read them cover to cover. I was in a sanitarium, so there wasn’t much else I could do in those days. They didn’t have teachers to go to the hospital and teach you.

“Although there wasn’t any effective treatment for tuberculosis and [my condition] didn’t look too good—people were dying to my left and to my right—I persisted. [Years later] when I did a surgery residency at Howard, I met a medical student from Nigeria. He told me the [Biafran] civil war had just ended and they needed dialysis desperately. I thought my life’s dream had come true, but during my two tours there, I lost 75 pounds and contracted malaria. It turned out the missionary field was not for me, and I decided to do a [kidney-transplant] fellowship at the University of Minnesota because it was a [relatively] new field.

“When I returned to Howard, I learned Black people were only 3 percent of all organ donors, yet were in the biggest need for transplants. I wasn’t sure how we would make a difference, but I knew this was something I had to do. Over 30 years, we performed about 400 transplants and brought hope to people who had kidney and liver disease.

Seventy-two years [after my illness], my reward has been to see those people I’ve been able to help have a second chance in life. But there’s still many more mountains to climb.”

—As told to Damare Baker