The three stones are easy to miss. Cut from granite and flush to the ground, weathered and surrounded by twisting tree roots, they rest before a row of townhouses in a leafy Mount Pleasant neighborhood in Northwest DC. Placed in the strip between the sidewalk and curb, each is engraved with a name and two dates, spans of time measured in decades.

I first learned about the stones through a neighbor’s online post trying to crowdsource information about their origin. From my nearby apartment, I went on a jog to investigate and found them on Kilbourne Place. Clearly, these were memorials of some kind—like the presidential monuments and war-remembrance statues dotting the city, only smaller and more intimate.

Who were they for? Why were they here? I started asking around, knocking on doors. Locals, it turned out, were as puzzled as I was. “People are always looking, wondering what they are,” one homeowner told me, peering down at the stones as a dog walker joined us to take a look. Some speculated that they were dedicated to cherished pets, yet the names—Robert, Jakob, and Charles—sounded like people. Others wondered if there had been a horrible accident on the block—though if that were the case, why would the ending years be different on each stone?

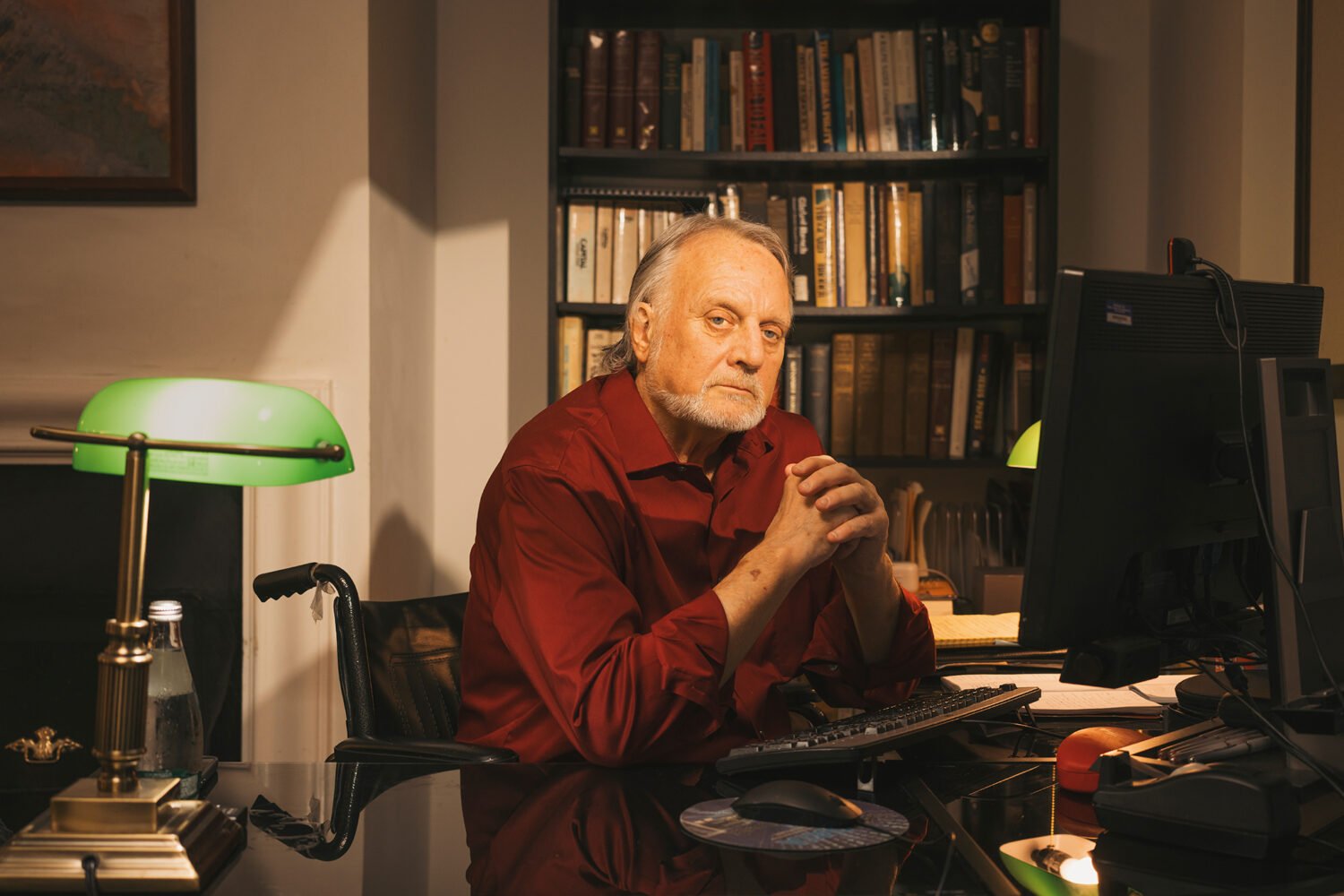

Still curious, I tried to find people who once lived in the neighborhood. I sent Facebook messages that went unread, mailed question-filled letters that returned few answers, called phone numbers that often produced a robotic “This phone number is no longer in service.” I spent months getting nowhere. Then one Friday evening, my phone rang. The caller sounded downright giddy.

“I know exactly about the plaques, because I planted them,” the voice said. “I was Chuck’s lover.”

The caller’s name was Larry. An old acquaintance of his had told him about my search. He talked. I listened. It was the first of many conversations to come—about a love story that began almost 50 years ago and was so solid in the face of prejudice, so lasting in the face of loss, it had to be remembered in stone.

The Dream

They met in Baltimore’s Wyman Park, brought together by chance. It was the summer of 1979, the era of bell bottoms and platform heels, Gloria Gaynor and Chic’s “Le Freak.” Both men were in their early twenties, chasing the hot stuff Donna Summer sang about. They found it in each other: Chuck Winney, a Johns Hopkins undergraduate, and Larry Martin, a regional-camp guide.

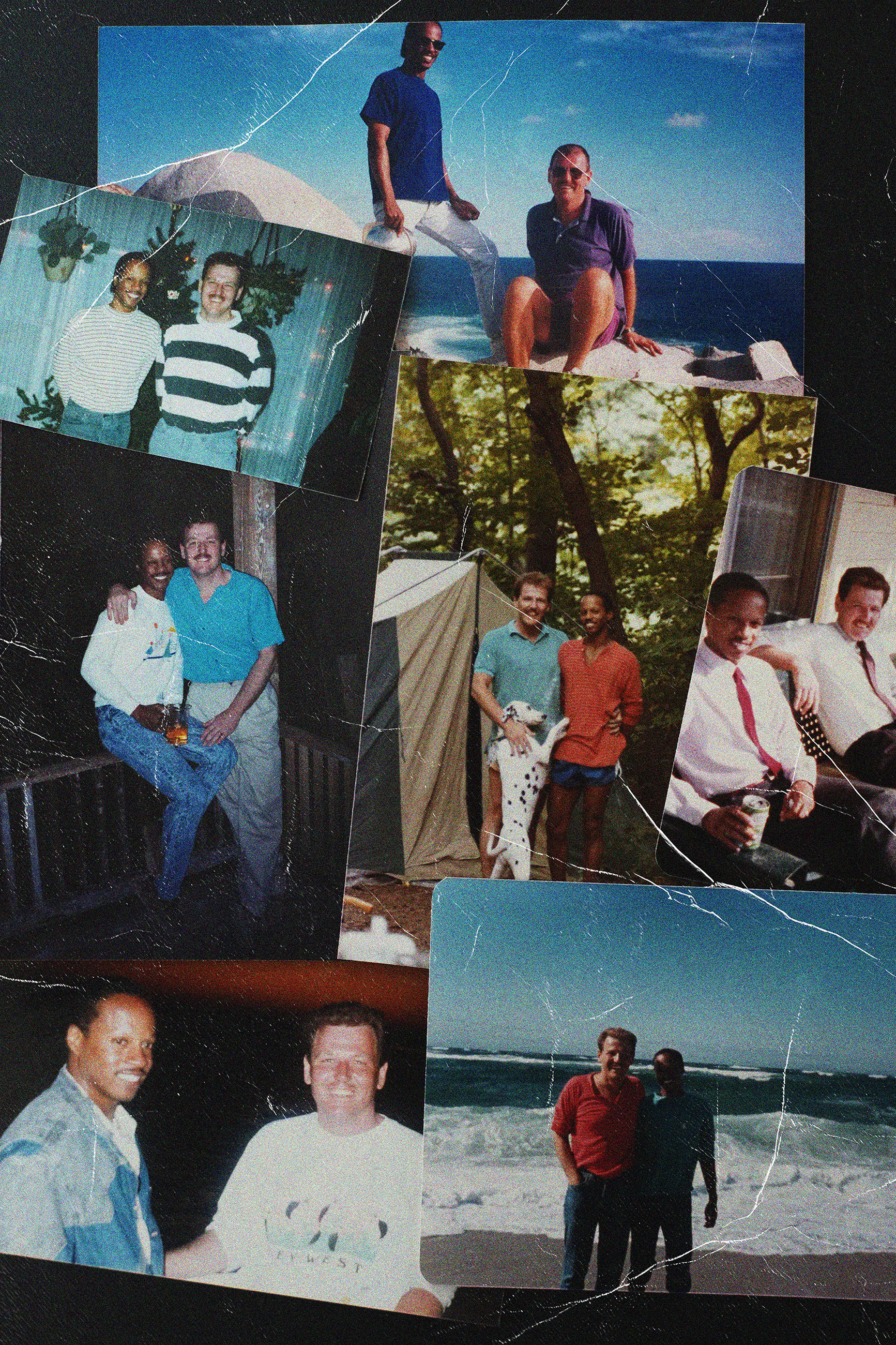

Their initial nights were spent on the sweaty, beer-soaked dance floors of neighborhood bars, beneath a rain of heavy kick drums and synthesizers. They were curious, exploring, and enticed. But it was the quieter daytime moments that brought them closer: Chuck’s simple charm and spotlight smile drew Larry in, while Larry’s booming personality teased Chuck out from his quieter self. “The chemistry between us two, it just felt really, really good,” Larry remembers.

Each had to be careful. Neither was out to his family—they shared a mutual pain of keeping secrets from the people they loved. The camp Larry worked at was run by the Boy Scouts of America, which at the time banned gay scouts and leaders. Then there was the matter of race. Larry was white. Chuck was Black. “We were unique in that sense,” Larry says. “You knew it because you didn’t see too many mixed-race couples, if at all. Back then, it wasn’t that accepting.”

Steeling their hearts against a world that could be hostile, they moved in together, occupying an apartment above a dry cleaner and surrounding themselves with open-minded friends. Larry began thinking ahead, about what he and Chuck could become. Chuck was more cautious, sometimes saying he felt things were moving too fast. About a year after the two met, Chuck left. He told Larry they were too young to settle down.

Larry was devastated. He felt the universal pain of being broken up with, alongside the more particular sadness of losing a first gay love. The years of bottled-up desires that had finally poured out. The nagging self-doubt that had melted away as someone else saw you in your wholeness. All of that comfort, ripped away.

Over the next few years, Larry tried to keep their spark alive. He sent cassette tapes filled with their favorite rhythm and blues to Chuck, who had moved to Las Vegas. He occasionally called, too—but Chuck shared little about his life, and less about his feelings for Larry, which always came back to some version of I love you, but . . . .

Then in 1983, it was Larry’s turn to get a call. Chuck wanted to see him. Despite not knowing how to book a plane ticket—or owning any luggage—Larry boarded his first-ever flight, holding a black garbage bag stuffed with clothes. The two spent a week together, enjoying Vegas, and didn’t talk much about what Chuck had been doing since their breakup. Instead, Larry was hopeful about their future. When could they get back together? “I would’ve liked it to happen the very next day,” Larry says.

Chuck said he needed time to think. Larry was living in DC, working in an accounting job for a fundraising organization. Chuck was interested in attending pharmacy school. He was accepted into Howard University’s program and moved to Washington—where he crammed for his new science classes and crammed himself into an apartment that Larry shared with a roommate. Considering the future, Chuck scribbled “DREAM” across an envelope. He placed one of his first prescriptions inside:

Perhaps we lost ourselves a few times, but our love came through. We’ve found each other again, a renewal of our love for each other.

Larry i love you more than i thought possible. I make a wish from the bottom of my heart—that we may never lose the love we feel . . . That we may maintain and continue to renew our love everyday.

That we may be as one someday and for the rest of our physical lives and beyond.

All my love,

Chuck

For Larry, the letter was the assurance he had been chasing. And now? The two needed more space. After all, Larry moonlighted as a bartender at Mr. P’s, the first gay club in Dupont Circle—and dammit, he wanted to throw his own tea dances. So Chuck and Larry pooled their savings and bought a three-story townhouse for about $100,000 in the then-gentrifying Mount Pleasant neighborhood. It was a fixer-upper, but really, how hard could remodeling be?

Back to Top

The Townhouse

Pretty soon, Chuck and Larry gave the tall, narrow brick townhouse on Kilbourne Place a nickname: Leaky Acres.

From its shoddy roof to its sagging floor, the place needed to be gutted. Chuck, who favored tidiness and sophistication, hoped remodeling would be quick. Larry knew better. The labor costs alone for a long list of improvements was more than the two could afford, so Larry bought tools and got to work on demolition. (A contractor friend handled rebuilding.) His style was improvisational. He’d rip up plumbing on a whim, then bust out some windows. Swinging his sledgehammer through walls and wooden beams, he sprayed early-1900s-style plaster—mixed with mortar and real horsehair—seemingly everywhere. He made an even bigger mess when he tried to clean out a paint can by putting it in the dishwasher.

One time, as Larry was tinkering with the electrical circuits, a loud zap echoed through the house. “Okay, we’re leaving now and going to have happy hour!” Chuck and some friends yelled to him as they fled to safety. “Come and join us if you’re still alive!”

Amid the chaos, Larry tried to entertain Chuck’s highbrow sensibilities. Chuck would inspect the previous owners’ questionable design choices, the left-behind greasy appliances, and, with a raised eyebrow and pointed finger, declare: This must go. He insisted to friends that the place needed a pop of color, one that could only be provided by that most exquisite of gay-coded kitchen accessories: Le Creuset cookware. The same friends called Chuck “Greta Garbo,” because his shy personality brought to mind the enigmatic Hollywood star. Watching costs, Larry encouraged Chuck to shop—at the nearby Goodwill. Chuck would shoot back, “Larry, you can suggest, but you know you are not going to get your way, honey.”

By 1985, the townhouse had become something of a central command station for the couple’s growing group of gay friends. Larry and Chuck welcomed roommates to fill the three floors of what had been a 12-person boarding house. One of them, Mark, came to Washington in part for work opportunities and in part to escape his hometown on the Eastern Shore, where he was often taunted for his sexuality.

Living with his new housemates, Mark says, “we put the G in gay.” Campy costumes were a requirement for Larry and Chuck’s over-the-top Halloween parties, with hundreds of friends jamming into a townhouse that looked more like a haunted mansion with its exposed walls and ceilings. The hosts dolled themselves up in dresses and called themselves the “Golden Girls of Mount Pleasant,” modeled after the sassy stars of the hit 1980s sitcom. Chuck was the dainty and opinionated Sophia. Larry fit naturally into the role of protective Dorothy. Robbie, the fourth housemate, was optimistic Rose, while Mark says he was delighted to be Blanche—“the slut!”

The house was also home to raucous annual gatherings kicking off the Pride celebrations around Dupont Circle. A parade of gay men and women would pack the front yard as the music of Chuck’s favorite divas—Aretha Franklin and Patti LaBelle—piped through the windows and rang down the street. The parties were brassy, full of gossip, and spritzed with outlandishness, just like the signature house cocktail: Cape Cods, filled to the rim with vodka, cranberry juice, and lime. Madonna’s anthems and Whitney Houston’s velvet “Woo!” transformed the little living room into a dance floor, bending its aging oak floors. Thanks to Chuck, though, it wasn’t all rowdy. When an older, soulful ballad came on, such as jazz great Nancy Wilson crooning, “I’m in the middle, lost in a spin—loving you and you don’t know how glad I am,” that was a sign he had taken over the playlist.

After more than five years together, Chuck and Larry’s love had deepened. Friends started referring to them as a single unit: “Chuck-and-Larry.” At parties, Larry, ever boisterous, would orbit from room to room—but always return to Chuck, who usually held court off to the side. On Sundays, the two went to church together, tending to their shared Christian faith. Other gay men in their social circle—the ones who longed for a serious relationship—would say they wanted something like Chuck-and-Larry. “The fact that they were opposites worked in their favor,” says Mark, their housemate. “I can’t imagine two Larrys together—it would be off the rails. I think they kind of counterbalanced each other.”

Christmastime was extra special, with the pair hosting a party to decorate their 12-foot tree. Chuck and Larry gathered around the tree with their friends and their dogs—a Dalmatian named Max and a Doberman named Blackie—and pose for self-timed photos. The warm vibes were intentional. Chuck and Larry knew that many of their friends were far from their own families, or worse, felt unaccepted by them because of their sexuality. “We bought the house knowing it would be a house for everybody who needed a place to go,” Larry says. “It was a challenge but worth it.”

“The place was a safe haven,” says Joe, another friend from that era.

Larry understood the pain of estrangement. When Chuck first moved into Larry’s old apartment, Larry says, one of his siblings saw a picture of them together that suggested they were more than just roommates. Word spread to Larry’s other brothers and sisters, so he decided to write a letter to his parents, hoping they would accept him. Instead, they sent Larry a handwritten letter with a far different message:

Larry, I’m sorry but I cannot accept your way of life. To me + Dad its very disgusting and with a colored its even worse. As far as you being born gay you’re absolutely wrong in that you made yourself that way.

We will have nothing to do with that part of you in anyway and we do not want to meet your so called lover. It makes me sick.

Your welcome in our home but only you, thats the way its got to be. We will never change. . . . And there’s no such thing as mixing colors. I’ll have to close as its only making me sick to think of it. Please don’t write me anymore on the subject.

Mom + Dad

Sharing the letter with Chuck, Larry was near inconsolable. Reading it hurt Chuck, too, because his relationship with his own mother, Thelma, was so central in his life. Thelma always encouraged Chuck as a young boy by saying, “That’s beautiful, child.” Years later, when Chuck got up the nerve to introduce Larry to his family, Thelma gave the men a wink—and pointed to the room she’d made up for them to stay in together.

It would have been easy for Chuck to feel hostility toward Larry’s parents. Instead, he grabbed Larry’s hand, held him, and said he hoped his parents’ feelings would soften. Larry vowed to Chuck that he wouldn’t respond to them until they called him. The ensuing silence lasted several years, until one day when Larry’s office phone rang. It was his mother, Ida, asking if he was coming home for the holidays. Larry said he would, but only if Chuck was welcome, too.

Ida said yes. On Christmas Eve, the couple walked into Larry’s parents’ place. The mood was tense. Some of Larry’s siblings gawked. Larry remembers leaving after only a few minutes, with the excuse that they were heading to see Chuck’s family in New York. Still, Larry says, “it was a breakthrough.” Chuck and Larry would continue to visit Larry’s parents—by themselves, no siblings—and while the parents never apologized, their hostility waned. A few years later when Ida passed away, Chuck again consoled Larry—this time from the front row of her funeral, sitting alongside Larry and his siblings.

Back to Top

The Portrait

Chuck and Larry found sunnier days together in Provincetown, an enclave at the tip of Cape Cod that long has been a favorite summer getaway for Washington’s LGBTQ community. It was there, in 1985, that Larry traced a big heart in the sand, lay down in the middle, and asked Chuck to marry him. Chuck said yes—quickly—and a few months later, the couple donned red ties and red rose boutonnières, holding hands at the altar of the gay-friendly Metropolitan Community Church in Washington.

This was seven years before DC legalized domestic partnerships between same-sex couples and 30 years before the Supreme Court decision that gave same-sex couples the right to marry nationally. Even if the government wouldn’t acknowledge their relationship, Chuck and Larry wanted to pledge their commitment to each other in the eyes of God.

Friends started referring to them as a single unit: “Chuck-and-Larry.” At parties, Larry, ever boisterous, would orbit from room to room—but always return to Chuck, who usually held court off to the side. On Sundays, the two went to church together, tending to their shared Christian faith.

“All that is mine I give to you,” Chuck said in his vows.

“I promise to be there when you need me and be there when you don’t,” Larry told Chuck.

Almost a decade of married life later, in 1994, the couple was cuddling in the second-floor bedroom of their Mount Pleasant house when Larry felt something ominous: a stiff lump in Chuck’s neck. Both men froze, then panicked. Chuck began to cry. Larry held him, whispering reassurances. “Let’s see what happens,” he said. They were in their late thirties, the prime of their lives, and felt like it. Chuck was healthy and active—he didn’t think he could be infected with HIV, the human immunodeficiency virus, because the two had been careful to avoid transmission risks. “Maybe,” Larry remembers saying, “we will be the lucky ones.”

Over the previous decade, AIDS had become a global health epidemic. The disease is the most advanced stage of infection for HIV, which slowly attacks the immune system, making it difficult to fight off infections and other illnesses. Today, antiretroviral drugs can allow people with the virus to live about as long as those without it. Between 1981 and 1996, by contrast, more than half of the 566,002 Americans diagnosed with AIDS died as a result of complications related to HIV—and in 1994, HIV became the leading cause of death among Americans ages 25 to 44.

The virus was especially feared within the gay community, where infection rates were higher and seeming federal indifference to a disease sometimes pejoratively referred to as “gay cancer” provoked anger and outrage. Feeling abandoned by broader society, gay men in DC and elsewhere did what they could to assist those facing AIDS alone. They delivered food. They made promises to take care of pets. At church, Chuck and Larry watched as more and more heart-shaped ornaments were hung on a tree of remembrance, honoring lost congregants and friends.

Two weeks and several tests after they discovered Chuck’s lump, doctors confirmed the worst. He had contracted HIV and would become one of more than 7,000 DC residents diagnosed with AIDS by 1994. Chuck told Larry, whose own tests were negative, that he wanted to keep his condition a secret. He started treatments with AZT, the first drug approved to treat the disease. He continued to exercise. He wanted to learn to play the piano, so Larry managed to move one in through their foyer and scheduled at-home lessons. Chuck’s rudimentary keys didn’t exactly sing, but his staccato melodies floated through their house anyway, making both men feel better.

Yet the disease took a toll. Chuck’s face thinned. His biceps flattened. His strength waned. It became hard to get out of the bathtub. When the couple began sitting down with friends to finally share Chuck’s diagnosis, many of them said they already knew—they could see it. Larry became Chuck’s main caregiver, while Chuck’s older sister, Charlene, eventually stopped working as a nurse to help them both at the townhouse. Visits from Charlene’s kids brightened Chuck’s days—when he started to lose clumps of hair due to the treatments, the kids helped shave their uncle’s head.

The ups and downs went on for more than a year and a half. At one point, Chuck’s temperature spiked to 104 degrees before plummeting to 90, prompting a long hospital stay and the discovery that because of his suppressed immune system, a fungal infection had spread to his face—ultimately requiring invasive surgery. In the spring of 1996, Chuck’s physician sat down with the couple and told them there wasn’t much else he could do. They left the hospital and drove to a video store so Chuck could pick out his favorite old films. Friends helped wheel—and then carry—Chuck to the second-floor bedroom, nestling him into the king bed. Larry stationed himself at a large bay window nearby, keeping watch. When he stepped away, Chuck would turn to his sister and ask, “Please look out for Larry.”

Charlene says this period with Chuck was one of the most meaningful of her life, as she got to spend time with many of the friends and neighbors she’d heard so much about. Laughs boomed out of the room as visitors told old stories and new ones, like the one about Larry leaving the car running in front of the hospital. Around the Fourth of July, Chuck’s dad came to the house—by himself, because Chuck’s mom had recently suffered a stroke, and also wanted the two men to have some time alone. Charlene was nervous, wondering how her father, whose demeanor was distant and stoic, would respond to Chuck. Father and son were left alone, and Chuck stayed up much later than usual for what Charlene believes was their longest conversation since her brother was a boy. When Charles Sr. finally came downstairs, Larry and friends were waiting in the backyard. Charles Sr.’s voice cracked as he acknowledged the group as Chuck’s family. “Thank you,” he said, “for taking care of my son.”

Throughout the night of July 10, 1996, Larry dabbed drops of morphine on Chuck’s lips, trying to ease his pain. Just before sunrise, he realized they were no longer working: Chuck kept putting out his hand, gesturing for more. Larry crawled into bed, trying to comfort his husband. He started to sing a hymn: “Jesus loves you, this I know, for the Bible tells me so / Little ones to him belong / They are weak, but He is strong.”

An hour later, at age 40, Chuck died.

Larry says that day felt like he was being crushed from all angles. The pain was dizzying. Friends huddled around him in the living room. Through the despair, a decision was made: Chuck’s funeral would be at church, and a memorial service would take place at the townhouse. “The attitude was we need to celebrate Chuck’s life and this was the place of so many happy times,” their friend Joe recalls. “It was a time we needed to be together and hang onto each other.”

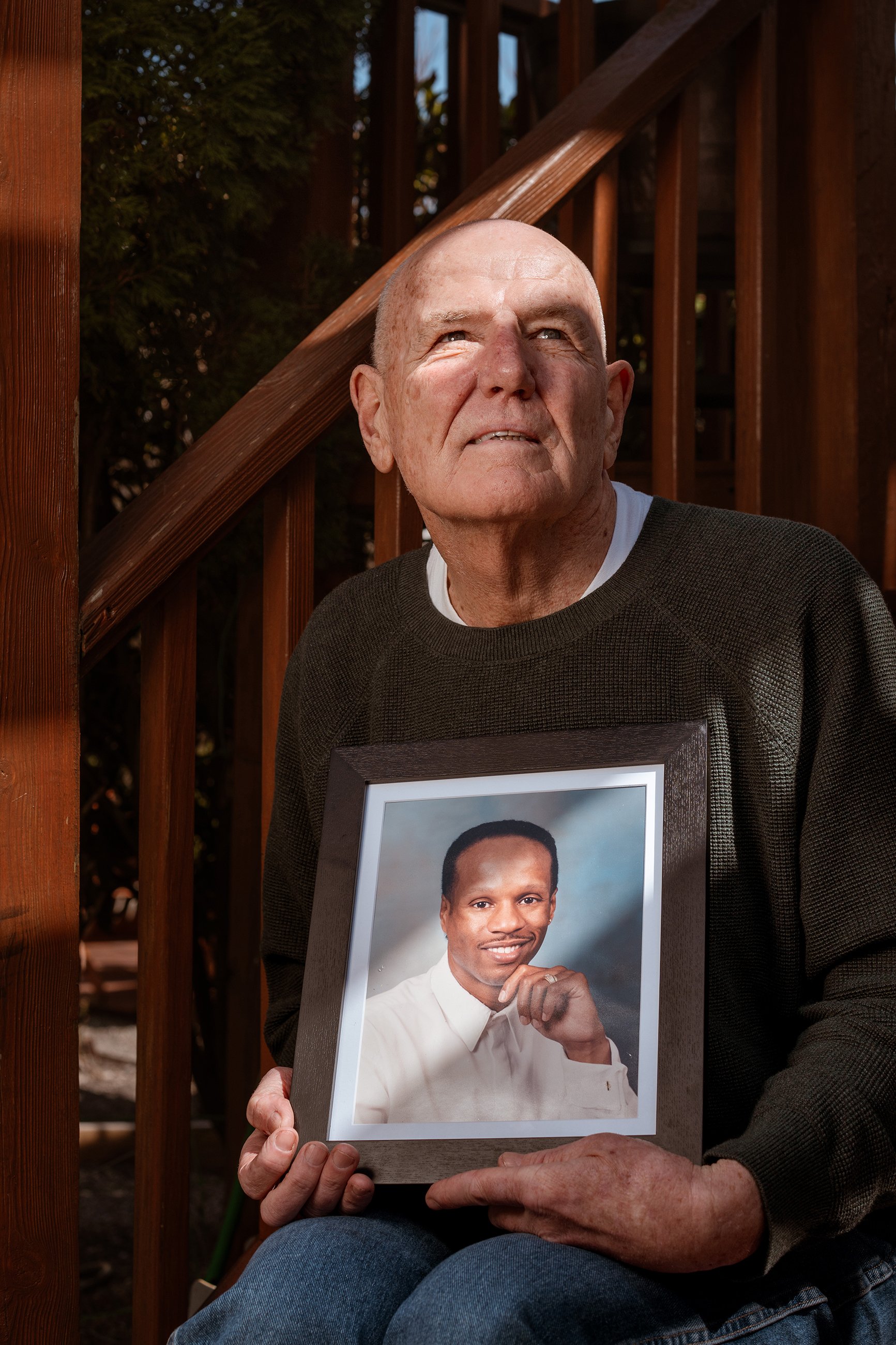

Before the service, Larry couldn’t escape a lingering image: Chuck, wearing an oxygen mask, one eye shut, worn down by illness. It was then that friends handed Larry a surprise gift—a framed portrait of his husband, arranged in secret by Chuck shortly after his diagnosis.

Larry looked down. Here was the love of his life, handsomely dressed in a crisp white shirt, his cheeks full and round, smiling with his disco-ball grin. When it was time to give Chuck’s eulogy, Larry told fellow mourners what the portrait meant to him: “The picture is one that really just says, ‘I told you I would be there. I told you it would be okay.’

“That, my friends, is what I mean when I tell you he was my best friend. Even though he left me, he took care of me. Goodbye for now, Chuck, and thanks. I will always love you.”

Back to Top

The Stones

Without Chuck, Larry didn’t feel that he could stay in the townhouse—or in the District. “In Washington, it was always Chuck-and-Larry, and I needed to learn how to exist again as just Larry,” he says. But before he boxed up the contents of the place and sold it, he helped leave something behind: the memorial stones.

Chuck wasn’t the neighborhood’s only resident lost to the AIDS epidemic. Jakob, a Peace Corps volunteer who loved to line-dance, had died from the disease in 1995. Robert, whom everyone called Helga for his exuberance and imposing stature, died from AIDS complications in 1998. Both men lived next door to the townhouse. Both were Chuck and Larry’s friends. Like Chuck, both died just as more effective and lifesaving therapies were becoming available—leaving their loved ones feeling extra cheated.

And so in 1999, grieving family members and lovers and regulars from the Chuck-and-Larry parties all gathered on Kilbourne Place for an unusual ceremony. They planted a square headstone for each man, together spanning about 47 footsteps between their houses. Before the end of the year 2000, at least 448,060 people died from AIDS nationwide—and here, three of them would be remembered.

“We all felt like we survived a war,” says Joe, their friend.

Larry left Mount Pleasant almost 30 years ago. He traveled to new places, a too-soon widower trying to make sense of it all, confiding to others that his husband had given him wings. Eventually, he settled in Provincetown, buying a home not far from where he’d proposed to Chuck in the dunes. Chuck’s portrait is inside.

Now almost 70, Larry still travels back to Washington every summer, where he visits his husband’s grave at a cemetery not far from the townhouse. During those trips, residents of his old block might peek out their windows and see an older gentleman looking down at the curious memorials along the curb. Through tears of grief and joy, he draws comfort from their presence and from what they represent, both unchanged after so much time.

“I tell people,” Larry says, “if you find love once, you’re blessed for life.”

The three stones are easy to miss. Cut from granite and flush to the ground, weathered and surrounded by twisting tree roots, they rest before a row of townhouses in a leafy Mount Pleasant neighborhood in Northwest DC. Placed in the strip between the sidewalk and curb, each is engraved with a name and two dates, spans of time measured in decades.

I first learned about the stones through a neighbor’s online post trying to crowdsource information about their origin. From my nearby apartment, I went on a jog to investigate and found them on Kilbourne Place. Clearly, these were memorials of some kind—like the presidential monuments and war-remembrance statues dotting the city, only smaller and more intimate.

Who were they for? Why were they here? I started asking around, knocking on doors. Locals, it turned out, were as puzzled as I was. “People are always looking, wondering what they are,” one homeowner told me, peering down at the stones as a dog walker joined us to take a look. Some speculated that they were dedicated to cherished pets, yet the names—Robert, Jakob, and Charles—sounded like people. Others wondered if there had been a horrible accident on the block—though if that were the case, why would the ending years be different on each stone?

Still curious, I tried to find people who once lived in the neighborhood. I sent Facebook messages that went unread, mailed question-filled letters that returned few answers, called phone numbers that often produced a robotic “This phone number is no longer in service.” I spent months getting nowhere. Then one Friday evening, my phone rang. The caller sounded downright giddy.

“I know exactly about the plaques, because I planted them,” the voice said. “I was Chuck’s lover.”

The caller’s name was Larry. An old acquaintance of his had told him about my search. He talked. I listened. It was the first of many conversations to come—about a love story that began almost 50 years ago and was so solid in the face of prejudice, so lasting in the face of loss, it had to be remembered in stone.

Back to Top

The Dream

They met in Baltimore’s Wyman Park, brought together by chance. It was the summer of 1979, the era of bell bottoms and platform heels, Gloria Gaynor and Chic’s “Le Freak.” Both men were in their early twenties, chasing the hot stuff Donna Summer sang about. They found it in each other: Chuck Winney, a Johns Hopkins undergraduate, and Larry Martin, a regional-camp guide.

Their initial nights were spent on the sweaty, beer-soaked dance floors of neighborhood bars, beneath a rain of heavy kick drums and synthesizers. They were curious, exploring, and enticed. But it was the quieter daytime moments that brought them closer: Chuck’s simple charm and spotlight smile drew Larry in, while Larry’s booming personality teased Chuck out from his quieter self. “The chemistry between us two, it just felt really, really good,” Larry remembers.

Each had to be careful. Neither was out to his family—they shared a mutual pain of keeping secrets from the people they loved. The camp Larry worked at was run by the Boy Scouts of America, which at the time banned gay scouts and leaders. Then there was the matter of race. Larry was white. Chuck was Black. “We were unique in that sense,” Larry says. “You knew it because you didn’t see too many mixed-race couples, if at all. Back then, it wasn’t that accepting.”

Steeling their hearts against a world that could be hostile, they moved in together, occupying an apartment above a dry cleaner and surrounding themselves with open-minded friends. Larry began thinking ahead, about what he and Chuck could become. Chuck was more cautious, sometimes saying he felt things were moving too fast. About a year after the two met, Chuck left. He told Larry they were too young to settle down.

Larry was devastated. He felt the universal pain of being broken up with, alongside the more particular sadness of losing a first gay love. The years of bottled-up desires that had finally poured out. The nagging self-doubt that had melted away as someone else saw you in your wholeness. All of that comfort, ripped away.

Over the next few years, Larry tried to keep their spark alive. He sent cassette tapes filled with their favorite rhythm and blues to Chuck, who had moved to Las Vegas. He occasionally called, too—but Chuck shared little about his life, and less about his feelings for Larry, which always came back to some version of I love you, but . . . .

Then in 1983, it was Larry’s turn to get a call. Chuck wanted to see him. Despite not knowing how to book a plane ticket—or owning any luggage—Larry boarded his first-ever flight, holding a black garbage bag stuffed with clothes. The two spent a week together, enjoying Vegas, and didn’t talk much about what Chuck had been doing since their breakup. Instead, Larry was hopeful about their future. When could they get back together? “I would’ve liked it to happen the very next day,” Larry says.

Chuck said he needed time to think. Larry was living in DC, working in an accounting job for a fundraising organization. Chuck was interested in attending pharmacy school. He was accepted into Howard University’s program and moved to Washington—where he crammed for his new science classes and crammed himself into an apartment that Larry shared with a roommate. Considering the future, Chuck scribbled “DREAM” across an envelope. He placed one of his first prescriptions inside:

Perhaps we lost ourselves a few times, but our love came through. We’ve found each other again, a renewal of our love for each other.

Larry i love you more than i thought possible. I make a wish from the bottom of my heart—that we may never lose the love we feel . . . That we may maintain and continue to renew our love everyday.

That we may be as one someday and for the rest of our physical lives and beyond.

All my love,

Chuck

For Larry, the letter was the assurance he had been chasing. And now? The two needed more space. After all, Larry moonlighted as a bartender at Mr. P’s, the first gay club in Dupont Circle—and dammit, he wanted to throw his own tea dances. So Chuck and Larry pooled their savings and bought a three-story townhouse for about $100,000 in the then-gentrifying Mount Pleasant neighborhood. It was a fixer-upper, but really, how hard could remodeling be?

Back to Top

The Townhouse

Pretty soon, Chuck and Larry gave the tall, narrow brick townhouse on Kilbourne Place a nickname: Leaky Acres.

From its shoddy roof to its sagging floor, the place needed to be gutted. Chuck, who favored tidiness and sophistication, hoped remodeling would be quick. Larry knew better. The labor costs alone for a long list of improvements was more than the two could afford, so Larry bought tools and got to work on demolition. (A contractor friend handled rebuilding.) His style was improvisational. He’d rip up plumbing on a whim, then bust out some windows. Swinging his sledgehammer through walls and wooden beams, he sprayed early-1900s-style plaster—mixed with mortar and real horsehair—seemingly everywhere. He made an even bigger mess when he tried to clean out a paint can by putting it in the dishwasher.

One time, as Larry was tinkering with the electrical circuits, a loud zap echoed through the house. “Okay, we’re leaving now and going to have happy hour!” Chuck and some friends yelled to him as they fled to safety. “Come and join us if you’re still alive!”

Amid the chaos, Larry tried to entertain Chuck’s highbrow sensibilities. Chuck would inspect the previous owners’ questionable design choices, the left-behind greasy appliances, and, with a raised eyebrow and pointed finger, declare: This must go. He insisted to friends that the place needed a pop of color, one that could only be provided by that most exquisite of gay-coded kitchen accessories: Le Creuset cookware. The same friends called Chuck “Greta Garbo,” because his shy personality brought to mind the enigmatic Hollywood star. Watching costs, Larry encouraged Chuck to shop—at the nearby Goodwill. Chuck would shoot back, “Larry, you can suggest, but you know you are not going to get your way, honey.”

By 1985, the townhouse had become something of a central command station for the couple’s growing group of gay friends. Larry and Chuck welcomed roommates to fill the three floors of what had been a 12-person boarding house. One of them, Mark, came to Washington in part for work opportunities and in part to escape his hometown on the Eastern Shore, where he was often taunted for his sexuality.

Living with his new housemates, Mark says, “we put the G in gay.” Campy costumes were a requirement for Larry and Chuck’s over-the-top Halloween parties, with hundreds of friends jamming into a townhouse that looked more like a haunted mansion with its exposed walls and ceilings. The hosts dolled themselves up in dresses and called themselves the “Golden Girls of Mount Pleasant,” modeled after the sassy stars of the hit 1980s sitcom. Chuck was the dainty and opinionated Sophia. Larry fit naturally into the role of protective Dorothy. Robbie, the fourth housemate, was optimistic Rose, while Mark says he was delighted to be Blanche—“the slut!”

The house was also home to raucous annual gatherings kicking off the Pride celebrations around Dupont Circle. A parade of gay men and women would pack the front yard as the music of Chuck’s favorite divas—Aretha Franklin and Patti LaBelle—piped through the windows and rang down the street. The parties were brassy, full of gossip, and spritzed with outlandishness, just like the signature house cocktail: Cape Cods, filled to the rim with vodka, cranberry juice, and lime. Madonna’s anthems and Whitney Houston’s velvet “Woo!” transformed the little living room into a dance floor, bending its aging oak floors. Thanks to Chuck, though, it wasn’t all rowdy. When an older, soulful ballad came on, such as jazz great Nancy Wilson crooning, “I’m in the middle, lost in a spin—loving you and you don’t know how glad I am,” that was a sign he had taken over the playlist.

After more than five years together, Chuck and Larry’s love had deepened. Friends started referring to them as a single unit: “Chuck-and-Larry.” At parties, Larry, ever boisterous, would orbit from room to room—but always return to Chuck, who usually held court off to the side. On Sundays, the two went to church together, tending to their shared Christian faith. Other gay men in their social circle—the ones who longed for a serious relationship—would say they wanted something like Chuck-and-Larry. “The fact that they were opposites worked in their favor,” says Mark, their housemate. “I can’t imagine two Larrys together—it would be off the rails. I think they kind of counterbalanced each other.”

Christmastime was extra special, with the pair hosting a party to decorate their 12-foot tree. Chuck and Larry gathered around the tree with their friends and their dogs—a Dalmatian named Max and a Doberman named Blackie—and pose for self-timed photos. The warm vibes were intentional. Chuck and Larry knew that many of their friends were far from their own families, or worse, felt unaccepted by them because of their sexuality. “We bought the house knowing it would be a house for everybody who needed a place to go,” Larry says. “It was a challenge but worth it.”

“The place was a safe haven,” says Joe, another friend from that era.

Larry understood the pain of estrangement. When Chuck first moved into Larry’s old apartment, Larry says, one of his siblings saw a picture of them together that suggested they were more than just roommates. Word spread to Larry’s other brothers and sisters, so he decided to write a letter to his parents, hoping they would accept him. Instead, they sent Larry a handwritten letter with a far different message:

Larry, I’m sorry but I cannot accept your way of life. To me + Dad its very disgusting and with a colored its even worse. As far as you being born gay you’re absolutely wrong in that you made yourself that way.

We will have nothing to do with that part of you in anyway and we do not want to meet your so called lover. It makes me sick.

Your welcome in our home but only you, thats the way its got to be. We will never change. . . . And there’s no such thing as mixing colors. I’ll have to close as its only making me sick to think of it. Please don’t write me anymore on the subject.

Mom + Dad

Sharing the letter with Chuck, Larry was near inconsolable. Reading it hurt Chuck, too, because his relationship with his own mother, Thelma, was so central in his life. Thelma always encouraged Chuck as a young boy by saying, “That’s beautiful, child.” Years later, when Chuck got up the nerve to introduce Larry to his family, Thelma gave the men a wink—and pointed to the room she’d made up for them to stay in together.

It would have been easy for Chuck to feel hostility toward Larry’s parents. Instead, he grabbed Larry’s hand, held him, and said he hoped his parents’ feelings would soften. Larry vowed to Chuck that he wouldn’t respond to them until they called him. The ensuing silence lasted several years, until one day when Larry’s office phone rang. It was his mother, Ida, asking if he was coming home for the holidays. Larry said he would, but only if Chuck was welcome, too.

Ida said yes. On Christmas Eve, the couple walked into Larry’s parents’ place. The mood was tense. Some of Larry’s siblings gawked. Larry remembers leaving after only a few minutes, with the excuse that they were heading to see Chuck’s family in New York. Still, Larry says, “it was a breakthrough.” Chuck and Larry would continue to visit Larry’s parents—by themselves, no siblings—and while the parents never apologized, their hostility waned. A few years later when Ida passed away, Chuck again consoled Larry—this time from the front row of her funeral, sitting alongside Larry and his siblings.

Back to Top

The Portrait

Chuck and Larry found sunnier days together in Provincetown, an enclave at the tip of Cape Cod that long has been a favorite summer getaway for Washington’s LGBTQ community. It was there, in 1985, that Larry traced a big heart in the sand, lay down in the middle, and asked Chuck to marry him. Chuck said yes—quickly—and a few months later, the couple donned red ties and red rose boutonnières, holding hands at the altar of the gay-friendly Metropolitan Community Church in Washington.

This was seven years before DC legalized domestic partnerships between same-sex couples and 30 years before the Supreme Court decision that gave same-sex couples the right to marry nationally. Even if the government wouldn’t acknowledge their relationship, Chuck and Larry wanted to pledge their commitment to each other in the eyes of God.

Friends started referring to them as a single unit: “Chuck-and-Larry.” At parties, Larry, ever boisterous, would orbit from room to room—but always return to Chuck, who usually held court off to the side. On Sundays, the two went to church together, tending to their shared Christian faith.

“All that is mine I give to you,” Chuck said in his vows.

“I promise to be there when you need me and be there when you don’t,” Larry told Chuck.

Almost a decade of married life later, in 1994, the couple was cuddling in the second-floor bedroom of their Mount Pleasant house when Larry felt something ominous: a stiff lump in Chuck’s neck. Both men froze, then panicked. Chuck began to cry. Larry held him, whispering reassurances. “Let’s see what happens,” he said. They were in their late thirties, the prime of their lives, and felt like it. Chuck was healthy and active—he didn’t think he could be infected with HIV, the human immunodeficiency virus, because the two had been careful to avoid transmission risks. “Maybe,” Larry remembers saying, “we will be the lucky ones.”

Over the previous decade, AIDS had become a global health epidemic. The disease is the most advanced stage of infection for HIV, which slowly attacks the immune system, making it difficult to fight off infections and other illnesses. Today, antiretroviral drugs can allow people with the virus to live about as long as those without it. Between 1981 and 1996, by contrast, more than half of the 566,002 Americans diagnosed with AIDS died as a result of complications related to HIV—and in 1994, HIV became the leading cause of death among Americans ages 25 to 44.

The virus was especially feared within the gay community, where infection rates were higher and seeming federal indifference to a disease sometimes pejoratively referred to as “gay cancer” provoked anger and outrage. Feeling abandoned by broader society, gay men in DC and elsewhere did what they could to assist those facing AIDS alone. They delivered food. They made promises to take care of pets. At church, Chuck and Larry watched as more and more heart-shaped ornaments were hung on a tree of remembrance, honoring lost congregants and friends.

Two weeks and several tests after they discovered Chuck’s lump, doctors confirmed the worst. He had contracted HIV and would become one of more than 7,000 DC residents diagnosed with AIDS by 1994. Chuck told Larry, whose own tests were negative, that he wanted to keep his condition a secret. He started treatments with AZT, the first drug approved to treat the disease. He continued to exercise. He wanted to learn to play the piano, so Larry managed to move one in through their foyer and scheduled at-home lessons. Chuck’s rudimentary keys didn’t exactly sing, but his staccato melodies floated through their house anyway, making both men feel better.

Yet the disease took a toll. Chuck’s face thinned. His biceps flattened. His strength waned. It became hard to get out of the bathtub. When the couple began sitting down with friends to finally share Chuck’s diagnosis, many of them said they already knew—they could see it. Larry became Chuck’s main caregiver, while Chuck’s older sister, Charlene, eventually stopped working as a nurse to help them both at the townhouse. Visits from Charlene’s kids brightened Chuck’s days—when he started to lose clumps of hair due to the treatments, the kids helped shave their uncle’s head.

The ups and downs went on for more than a year and a half. At one point, Chuck’s temperature spiked to 104 degrees before plummeting to 90, prompting a long hospital stay and the discovery that because of his suppressed immune system, a fungal infection had spread to his face—ultimately requiring invasive surgery. In the spring of 1996, Chuck’s physician sat down with the couple and told them there wasn’t much else he could do. They left the hospital and drove to a video store so Chuck could pick out his favorite old films. Friends helped wheel—and then carry—Chuck to the second-floor bedroom, nestling him into the king bed. Larry stationed himself at a large bay window nearby, keeping watch. When he stepped away, Chuck would turn to his sister and ask, “Please look out for Larry.”

Charlene says this period with Chuck was one of the most meaningful of her life, as she got to spend time with many of the friends and neighbors she’d heard so much about. Laughs boomed out of the room as visitors told old stories and new ones, like the one about Larry leaving the car running in front of the hospital. Around the Fourth of July, Chuck’s dad came to the house—by himself, because Chuck’s mom had recently suffered a stroke, and also wanted the two men to have some time alone. Charlene was nervous, wondering how her father, whose demeanor was distant and stoic, would respond to Chuck. Father and son were left alone, and Chuck stayed up much later than usual for what Charlene believes was their longest conversation since her brother was a boy. When Charles Sr. finally came downstairs, Larry and friends were waiting in the backyard. Charles Sr.’s voice cracked as he acknowledged the group as Chuck’s family. “Thank you,” he said, “for taking care of my son.”

Throughout the night of July 10, 1996, Larry dabbed drops of morphine on Chuck’s lips, trying to ease his pain. Just before sunrise, he realized they were no longer working: Chuck kept putting out his hand, gesturing for more. Larry crawled into bed, trying to comfort his husband. He started to sing a hymn: “Jesus loves you, this I know, for the Bible tells me so / Little ones to him belong / They are weak, but He is strong.”

An hour later, at age 40, Chuck died.

Larry says that day felt like he was being crushed from all angles. The pain was dizzying. Friends huddled around him in the living room. Through the despair, a decision was made: Chuck’s funeral would be at church, and a memorial service would take place at the townhouse. “The attitude was we need to celebrate Chuck’s life and this was the place of so many happy times,” their friend Joe recalls. “It was a time we needed to be together and hang onto each other.”

Before the service, Larry couldn’t escape a lingering image: Chuck, wearing an oxygen mask, one eye shut, worn down by illness. It was then that friends handed Larry a surprise gift—a framed portrait of his husband, arranged in secret by Chuck shortly after his diagnosis.

Larry looked down. Here was the love of his life, handsomely dressed in a crisp white shirt, his cheeks full and round, smiling with his disco-ball grin. When it was time to give Chuck’s eulogy, Larry told fellow mourners what the portrait meant to him: “The picture is one that really just says, ‘I told you I would be there. I told you it would be okay.’

“That, my friends, is what I mean when I tell you he was my best friend. Even though he left me, he took care of me. Goodbye for now, Chuck, and thanks. I will always love you.”

Back to Top

The Stones

Without Chuck, Larry didn’t feel that he could stay in the townhouse—or in the District. “In Washington, it was always Chuck-and-Larry, and I needed to learn how to exist again as just Larry,” he says. But before he boxed up the contents of the place and sold it, he helped leave something behind: the memorial stones.

Chuck wasn’t the neighborhood’s only resident lost to the AIDS epidemic. Jakob, a Peace Corps volunteer who loved to line-dance, had died from the disease in 1995. Robert, whom everyone called Helga for his exuberance and imposing stature, died from AIDS complications in 1998. Both men lived next door to the townhouse. Both were Chuck and Larry’s friends. Like Chuck, both died just as more effective and lifesaving therapies were becoming available—leaving their loved ones feeling extra cheated.

And so in 1999, grieving family members and lovers and regulars from the Chuck-and-Larry parties all gathered on Kilbourne Place for an unusual ceremony. They planted a square headstone for each man, together spanning about 47 footsteps between their houses. Before the end of the year 2000, at least 448,060 people died from AIDS nationwide—and here, three of them would be remembered.

“We all felt like we survived a war,” says Joe, their friend.

Larry left Mount Pleasant almost 30 years ago. He traveled to new places, a too-soon widower trying to make sense of it all, confiding to others that his husband had given him wings. Eventually, he settled in Provincetown, buying a home not far from where he’d proposed to Chuck in the dunes. Chuck’s portrait is inside.

Now almost 70, Larry still travels back to Washington every summer, where he visits his husband’s grave at a cemetery not far from the townhouse. During those trips, residents of his old block might peek out their windows and see an older gentleman looking down at the curious memorials along the curb. Through tears of grief and joy, he draws comfort from their presence and from what they represent, both unchanged after so much time.

“I tell people,” Larry says, “if you find love once, you’re blessed for life.”

This article appears in the June 2025 issue of Washingtonian.