Contents

What time do you go to bed? For most locals, the answer falls somewhere between the 10 pm news and the end of The Late Show With Stephen Colbert. But in this weird and multitudinous town, plenty of people do stay up all night. Some are at work (collecting trash, guarding art) while others are at play (drinking and gambling, gawking at nude dancers). We sent reporters out at each hour of the night to see for themselves what happens after the 9-to-5 crowd calls it a day.

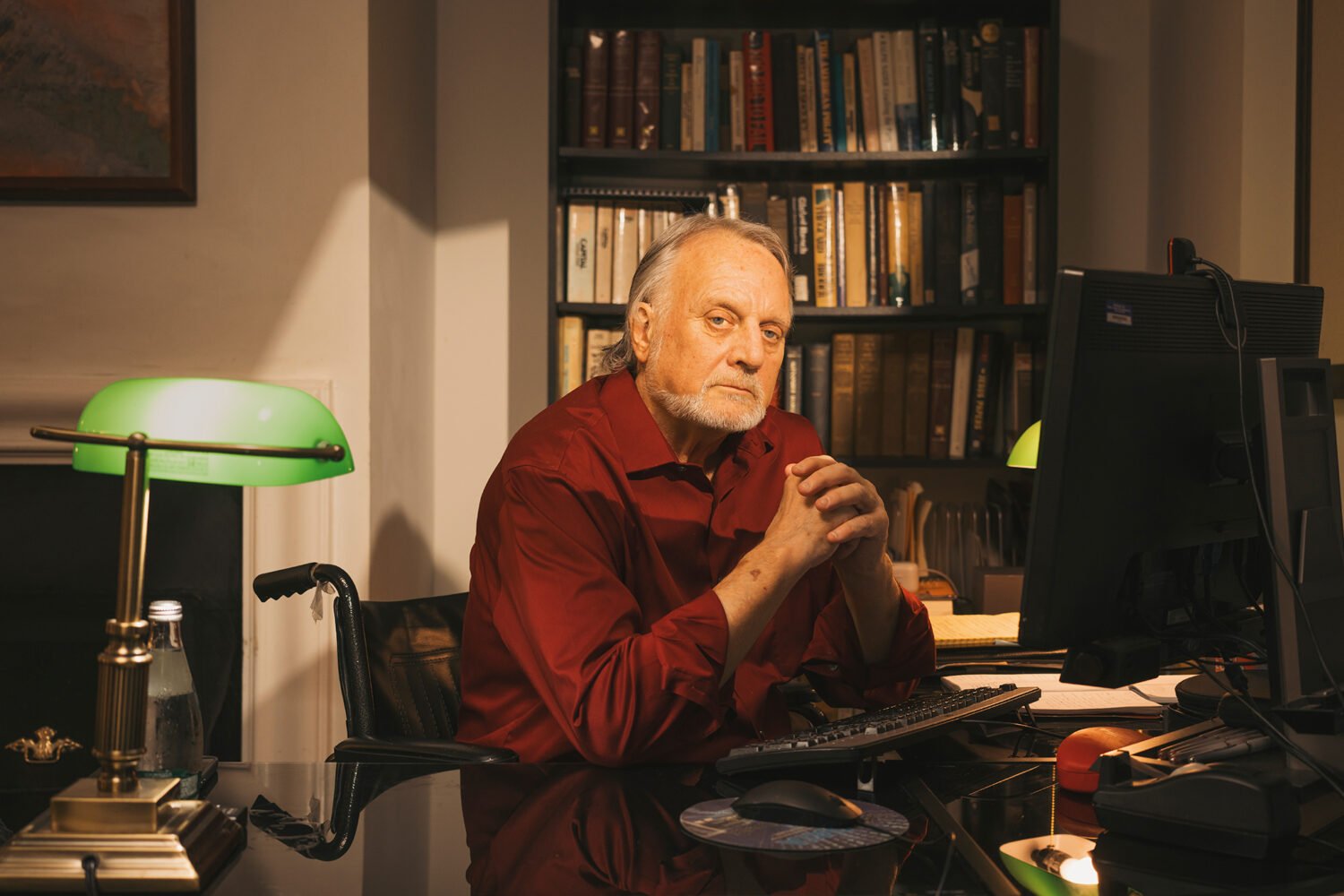

With a Museum Security Guard

Ralph A. Richardson spent more than 25 years as a DC police officer, working the overnight shift in Southeast’s Seventh District. “It’s a lot of crime, a lot of, um . . . activities,” he says. “It was always something going on.” These days, he still works late hours—midnight to 8—but the job is considerably more chill. Richardson is the night security officer at the National Museum of Women in the Arts, and he spends much of his shift alone in the museum, making rounds through the galleries or filling out paperwork and watching video monitors in the security office.

The historic Classical Revival building was once a Masonic temple; its ornate architecture is impressive and—when it’s late at night and the place is mostly empty—kind of unsettling. It’s the sort of place where, if such things exist, one might expect to encounter the supernatural. Richardson never has. “No ghosts,” he says, standing in the museum’s imposing marble atrium at the start of his shift. “Sometimes when I walk around, I’m thinking I’m hearing something, but, you know, it may be the wind, the rain. At first, it was a little different, a little eerie. After a while, you get yourself used to it.”

Typically, Richardson’s interactions are of a more earthly nature. Late-night passersby sometimes ask if they can come inside to use the bathroom or charge their phones. (They can’t.) He has a good relationship with unhoused people in the neighborhood (“You have to have a little empathy,” he says), but things can get a bit chaotic in the area, with nearby McDonald’s and Wawa outposts both open 24 hours. “People do a lot of partying and things down here,” he says. “You think you’re in New York with so many people, the hustle and bustle.” He once foiled a robbery in progress outside after he spotted it on a security camera.

But inside the museum, that all feels far away—it’s just Richardson, a small cleaning staff, and a whole bunch of art. So how much does he actually look at the museum’s offerings? “A lot, believe it or not. After a while, you get to know what’s there. Seeing some of this beautiful artwork makes you look at things from a different lens.” His favorite is a Mary Ellen Mark photograph of a young couple dressed for their high-school prom, which until recently hung on the first floor. It makes him think of his own graduation, his own high-school prom.

The overnight shift lends itself to that kind of quiet contemplation. “It’s really peaceful,” Richardson says. “Some jobs, it’s like, wow, it’s going to be a long, long day. But it sort of flows like water, you know? It’s like, ‘Ah, yeah, this is good.’ Time goes by really fast.”

—Rob Brunner

With a Trash Collector

It’s 1 am on the corner of V Street and Georgia Avenue, and Dewaun Jenkins has been driving his trash-collection truck through Northwest DC for nearly four hours. Jenkins typically does an eight-and-a-half-hour shift, and today he’ll be behind the wheel until 6 am. “There’s a lot of stuff going on: a lot of parties, people that are intoxicated, people who don’t have a place to go,” he says. “In all of that, we have to get the trash.”

Sitting behind the wheel of the huge vehicle, Jenkins constantly looks in the mirrors and out the windows. He never plays music while driving; the only sounds are the banging of cans and the whine of the crushing mechanism. Driving in darkness means he needs to be keenly aware, since hazards are plentiful: night cyclists, oblivious pedestrians, Ubers swerving into side lanes. Jenkins keeps watch so the crew can focus on the cans. “Everything happens fast,” he says. “I can pay attention to everyone at once and still keep the truck moving.”

If Jenkins is the eyes, the collectors are the muscle. Once the truck comes to a stop, the two sanitation technicians, James Young and Ronald Jones, hop off the back and begin a well-oiled relay race. One opens the can lids, deftly running up the street like he’s scoring points in a video game. The other follows, dumping each can into the back of the truck. While rats are an issue round the clock, they’re especially active at night. Often when the collectors approach, the rodents will make noise and scurry out.

At about 1:30, the truck rounds the corner at a McDonald’s, moving toward some dorms at Howard University. It’s a weekday, and things are relatively calm; the action ramps up on weekends, because this route goes through some of DC’s busiest nightlife corridors. Sometimes, drunk passersby will try to jump on the truck and do the collection themselves. “That’s the craziest thing,” says Jenkins. “They want to help, but it’s the most intoxicated people.” At one point, the vehicle gets stuck behind a man in tall red boots and a leather vest with no shirt underneath. Standing at the side of the street, face aglow from his phone as he scrolls, he doesn’t even seem to register the hulking truck behind him.

By the end of the night, Jenkins and his crew will have emptied some 450 cans. Though the work is often under-appreciated, Jenkins knows he’s making a difference. “I’m from here, so I enjoy cleaning up because I live here,” he says. “I’m cleaning up my community.”

—Daniella Byck

With Dancers at a Strip Club

When the lights come up at the Good Guys Club and the music shifts from pounding rap to crooning country and the sweating martini glasses are whisked from the bar, the big red digital clock reads 2 am. Actually, the time is 1:48—the clock is set 12 minutes fast to inject some urgency into the last straggling patrons, pushing them out the door before close. Among them is a drunk guy sipping on a Red Bull and watching a dancer hop off the pole onto her clear platform stilettos and totter upstairs to change.

The bartender, Jordan, worked a double today. She’s been here since just before noon. In a low-cut black leotard with artful rips in the bodice, she settles the last of her checks as an assortment of off-duty dancers help clean up. One collects empties, baring flesh whenever she bends, while another in fishnets and a bra grabs soiled white linens from tables, then tosses them, rumpled, onto the stage.

Sometimes, at the end of the night, the mood is gleeful—dancers goof off in the locker room, do rap battles, blast their music and twerk—but tonight, a rainy Tuesday, they’re tired. Everyone’s ready to go home. “I want Taco Bell so bad, but it’s closed,” says Utopia, who’s been on and off the pole all night. Still, her thick makeup looks fresh; blond curls cascade down her back. By 2:10, she’s upstairs in the changing room, downshifting from her stage clothes into sneakers and a purple tie-dyed sweatsuit, tapping at her phone with lime nails.

The changing room is a fluorescent, mirror-lined space with fraying chairs and small plastic lockers, water bottles and takeout containers strewn about. There, Utopia is grousing. “Ever since the federal-government situation, it’s been really hard to make money,” she says. “Everyone’s holding onto their dollars because they’re scared about getting fired or having to move.” Another dancer, Pineapple, agrees. Earlier, when Utopia was onstage, Pineapple tipped her from her own pocket, trying to set an example for the crowd. It didn’t work. Recalling this, Pineapple is indignant. “Like, are you guys not seeing her?” she says.

Some nights, Utopia goes to the MGM National Harbor after work to gamble and unwind, maybe drink a little more. Other nights, she’ll get a kebab at the 24-hour place in Crystal City, one of the best spots she knows that’s open late. But generally, she heads home to Fairfax to sleep. In her other life—her daylight one—Utopia is a personal-care assistant, helping the ill and disabled with their everyday tasks. She’s working toward starting her own business. Tomorrow, she can’t sleep in; she has client meetings at 11 and 2.

Downstairs, the last of the dancers are passing the bar in sweatsuits or oversize T-shirts, lugging duffels stuffed with fishnets and heels. They cluster by the door, waiting for the burly ex-cops working security to escort them to their cars. At the bar, the manager fills out paperwork. When he’s done, he’ll take tonight’s cash upstairs to the heavy safes in the club’s dusty office, which is lined with a wall of security monitors and a whiteboard to record totals for each shift.

“Jordan, let’s goooo!” a dancer shouts from the exit, and Jordan pops out from behind the bar holding a thick stack of bills. She tips out the security guys, says something in Spanish to the barback, then lugs her bag to the door. All afternoon and night, she’s been on her feet, serving drinks, chatting up men with the music rattling her brain. As she disappears onto Wisconsin Avenue, into the rainy night, she’s already relishing the silence.

—Sylvie McNamara

With Servers at a 24-Hour Diner

Even on a Saturday night, DC can feel pretty deserted at 3 am. But at the Diner on 18th Street in Adams Morgan, the peak overnight crowds haven’t even arrived yet. On a recent weekend night around that time, music is blaring throughout the restaurant, with Future and Kendrick Lamar energizing the line cooks in the kitchen as they get ready for what’s about to come. There aren’t many diners right now—the front-of-house staff has been taking a breather. Most neighborhood bars close at 3 am, though. The rush is about to begin.

Just 20 minutes later, every table in the place is occupied with raucous, seemingly inebriated people. They’ve come from all over central DC, since there aren’t many other choices for a full meal at this hour.

During the pandemic, the Diner paused its 24-hour service, but this year it finally went back to all-night operations. Owner Constantine Stravopoulos brought on a fellow Greek countryman, Iason Demos, to oversee the return. “Athens is a 24-hour city,” Demos told me earlier. “It’s in our culture to have a place you can go all night for a coffee, a drink, and food.”

By 3:30, the atmosphere at the Diner is less Athenian than quintessentially Washingtonian. One big, noisy table is filled with Commerce Department staffers eating chicken and waffles. At the counter, two just-acquainted patrons are deep in conversation: David, a tux-sporting lobbyist, is talking about his evening at the Swiss Embassy’s after-party for the White House Correspondents’ Dinner. His much younger interlocutor, Josh, is wearing a mesh tank top; he’s fresh off a house party in a Columbia Heights basement. A few stools down, a quiet solo diner with dreads is watching anime on his phone while his cat peeks out from a carrier on the next stool.

In the middle of it all are servers Katherine Hawkins, who frequently works this graveyard shift, and Khalil Malloy, who today has already been here nearly 12 hours, filling in for a worker who couldn’t make it. Hawkins remains impressively good-natured as things heat up. A long ribbon of order tickets for the kitchen now dangles almost to the floor from the printer: peanut-butter milkshake, loaded nachos, cheesy tots, fried chicken, French toast.

At this hour, people eat fast, and by 4 am the crowd has already started to thin. It’s been a quiet night. Hawkins says things can get rowdy, from roughhousing (she’s seen diners dive over the top of booths) to actual fights (patrons have menaced other tables with steak knives). One middle-aged guy got angry when his offer to pay the check for a table of young women was politely declined.

But mostly, the vibe is positive. “You’re the calm in other people’s storm,” Malloy says. And often, working overnight leads to engaging interactions. At one point, Hawkins had a conversation with a solo diner, who, among other things, wanted to know what higher power she believed in. “The customers tend to be super open and forthright about politics and religion,” Hawkins says. “Especially after they’ve been drinking.”

—Ike Allen

With Gamblers at a Casino

The casino at MGM National Harbor is open 24 hours, but the gleaming faux-marble bar in the center of the main room closed hours ago, and since then the crowd has had to hunt down cocktail servers in order to remain lubricated. The alcohol is still flowing at 4 am (the casino is exempt from Maryland’s usual serving cutoff time), and most patrons seem to fall somewhere on the spectrum between buzzed and wasted. At one roulette table, the croupier—sporting a purple pinstripe shirt and a seen-it-all demeanor—drops the ball into the wheel with practiced dispassion.

Things are feeling tense, as several players appear to be losing significant money. “Don’t play this shit, man,” cautions a patron watching the action. He’s personally down only $25 for the night, which could be a lot worse, judging by all the temple-rubbing going on at the table he’s observing. What is he doing at the casino at this notably late hour? “Drunk,” he says, clearly under the impression that no further explanation is needed. “You know this place got robbed a few weeks ago?” The heist he’s referring to actually happened in 2024, but inside the fluorescent glare of the casino, time doesn’t feel real anyway.

Not far from the roulette dealer, a glammed-up woman suddenly starts to scream unintelligibly. With a fabulously manicured hand, she grabs one of her friends by the jaw, the way you would to remove a foreign object from a toddler’s mouth. She tightens her grip and twists her target’s face—hard. The woman is still shouting as a security guard ushers her to the exit with the agility of somebody who handles this sort of situation all the time.

A bald guy now materializes with two cigarettes in hand, having been drawn over by the screaming woman on his way to order another drink. He introduces himself by pointing to his neck, on which his name is tattooed in fading ink. His pupils are the size of poker chips. He launches into a story about how he spent time living underneath the White House, somehow, and once trained with Bruce Lee. (We’re unable to pose follow-up questions because he’s talking too quickly for anyone to interrupt him.) He then serenades the crowd with what he says is an original song: “Stay in the moment / Act like you want it / You got me twisted / Now I really wanna bone it.” This performance has the unintended effect of dispersing much of the crowd. Some seem headed home; others regroup at a neighboring cluster of slot machines to keep gambling.

Nobody appears particularly fazed by any of this—according to one dealer on duty, it’s all pretty typical for a weekend night. It’s now nearing 5 am, and the sun will soon come up. Stragglers in the casino won’t have any idea. There are no windows; the lighting inside remains consistently bright no matter the time of day.

The chaotic scene around the roulette table has settled. The dealer continues to spin the wheel. Nearby, blackjack players double down and slot loyalists zone out in front of whirring cherry icons. An employee cruises by on a four-wheeled floor-scrubbing machine. Guards by the entrance watch as guests stream out—crossing paths with new arrivals who flash their IDs for entry. One of the guards is asked how these early-morning arrivals seem. He responds with a single, familiar word: “Drunk.”

—Kate Corliss

With a TV Reporter on the Scene

NBC4 Washington reporter Joseph Olmo is outside DC’s police headquarters, preparing to file his report on a shooting. He was assigned the story hours earlier at the beginning of his shift, when he called into the office to talk to his editor. There’d been an incident on Georgia Avenue—a 19-year-old dead, a 15-year-old in the hospital. Another murder in a city that still sees way too many.

Now it’s 5:45 am, and Olmo has gathered the facts and written a script. By the time he got the assignment at 3:30, the cops had already processed the crime scene and there was nothing there to see, so he decided to meet cameraman Brooks Meriwether at the MPD building, which will be the backdrop for his broadcast.

Just before 6, Olmo places his police scanner and two phones on a portable table. He inserts an AirPod into one ear so he can hear the studio, then waits for his cue. Moments later, Olmo is live on the air, delivering his report on the shooting.

On camera, Olmo is an energetic presence, whether he’s covering a crime or a blizzard or the opening of the Go-Go Museum. That charisma comes naturally: Neither he nor Meriwether drinks coffee as they report stories. “This job has enough adrenaline to keep you up,” Olmo says. Loud music on the car stereo helps. (Coldplay, Avicii, and reggaeton are favorites.) The mood is usually upbeat, though things do get intense. The night a helicopter collided with a plane over the Potomac was the longest of Olmo’s career. He and Meriwether reported at Hains Point until 6:55 am, then spent the rest of the day at the airport. He worked 16 hours; Meriwether was on duty for 36.

After Olmo wraps up his account of the Georgia Avenue murder, he and the anchors discuss how violent crime is actually down, just for some context. In 30 minutes, Olmo will deliver another on-camera report on the incident, then he and Meriwether will head to Potomac for their next assignment: A historic Black church is reopening after being devastated by flooding in 2019. That will be on the 11 am news, and they’re done. Maybe they’ll go to a diner to debrief over corned-beef hash and smoothies. Tomorrow, they’ll do it all again—more news, another crime, the relentless pursuit of routine local news. “Anybody can see the flashing lights,” Olmo says, “but we’re the ones who go figure out what happened.”

—Andrew Beaujon

With Firefighters and EMTs

It’s a rainy Wednesday morning inside DC’s largest firehouse, Engine Company No. 16, and the bad weather has brought a quieter-than-normal shift. Captain Derek Brachetti sits at a desk between the garage doors, where he monitors a live feed of calls coming into all the DC Fire companies. Coded phrases flash onto his screen. “BLS unconscious,” one says, which means a patient needs basic life support on the scene. That might include administering Narcan or oxygen. “ALS” indicates a request for advanced life support, required when there’s the likelihood of major injuries, as with a rollover crash that the overnight crew responded to a few hours ago near Farragut Square.

Right now, these calls are all for other firehouses—the ambulance, fire trucks, and additional emergency vehicles of various types sit parked behind Brachetti, ready if needed. “We are one of the few professions where we don’t get to do our profession every day,” the captain says. Many of the calls they tend to get are relatively routine: helping elderly residents with medical issues or treating overdoses on the city’s streets. Significant fires aren’t as common, though firefighter Tim Lehman—a decade-plus veteran—prefers those kinds of emergencies. “It’s the adrenaline,” he says, plus those interactions with the public can be more positive. In contrast, a recent overdose patient leaned over while being transported to the hospital and bit a paramedic’s ear—“like Mike Tyson,” Brachetti says. Gratitude isn’t always among the job’s rewards.

Engine Company No. 16 occupies a historic firehouse near 13th and L streets, Northwest. The company consists of 104 first responders, with 19 of them on duty at any given time, typically working 24-hour shifts. The daily changeover is happening soon, and most of the next shift’s firefighters have arrived early, giving themselves time to eat, prep their equipment, and catch up with colleagues before any rush-hour calls start coming in. The room is comfortable, with worn-in leather couches and a large table at the center. Countertops are covered in cereal boxes, coffee cups, and a surprisingly large number of bananas. The atmosphere is friendly, relaxed. “It’s a second family,” says Brachetti. Part of that bond comes from sharing a job that can be intense and emotionally taxing in a way civilians can’t fully understand. “We see things people aren’t meant to see,” Brachetti says. “People always ask, ‘What’s the worst thing you’ve seen?’ And it’s like, do you really want to know?”

—Kate Corliss

This article appears in the July 2025 issue of Washingtonian.