When Craig Holman first came to, he found himself in George Washington University Hospital hooked up to machines.

His ribs, hip, and knee were shattered. His ankle, too. He had suffered a brain bleed.

The victim of an early-March car crash—another driver struck Holman’s 2002 stick-shift Saturn after running a red light on Pennsylvania Avenue—Holman would spend a week in intensive care and three more in various hospital wards. Surgeries would follow surgeries. Much of the time, he couldn’t leave his bed without assistance.

And still he couldn’t stop thinking about Donald Trump.

For hours and hours, Holman would fixate on the newscasts emanating from the TV above his bed. Body broken, his mind seethed at what he saw as gross abuses of power by the President: firing thousands of federal workers, issuing massive tariffs, targeting law firms perceived to have worked against his political or personal interests, letting his Department of Government Efficiency run amok. Holman wasn’t happy with Congress, either, which he viewed as feckless, a legislature surrendering its constitutional clout to an overstepping executive.

“You’re sitting there, watching Trump on the news doing some obvious violation of the law, and you’re thinking, ‘I’d be filing a complaint right now if I were home!’ ” Holman says.

Of that, there’s little doubt. The 69-year-old Holman is a leading member of a peculiar Washington tribe: advocates for good government. Also known as “goo-goos,” they fight to regulate lobbying, limit the influence of money in politics, keep elected officials honest, and otherwise “drain the swamp” in the pre-Trumpian sense of the phrase.

For 23 years, Holman has been on the frontlines working as the government-affairs lobbyist for Public Citizen, the progressive nonprofit founded a half century ago by consumer advocate Ralph Nader. In the best of times, the job can feel thankless, even Sisyphean. Outnumbered and outspent, goo-goos perpetually push the rock of reform up Capitol Hill, only to be pulled back down by the stubborn gravity of wealth and self-interest.

Washington is home to a peculiar tribe: good government advocates known as “goo-goos,” who fight to regulate lobbyists, reform political-money laws, keep lawmakers honest, and “drain the swamp” in the pre-Trumpian sense of the term.

And these are not the best of times. Between an ongoing explosion of political spending and Trump’s return to the White House, goo-goos are on their back foot, confronting a new crisis almost daily. To wit: As emergency workers rescued Holman by cutting through both his car and his beloved leather jacket, the President signed an executive order establishing a government Strategic Bitcoin Reserve, never mind that Trump is heavily invested in the World Liberty Financial crypto-trading platform and launched an eponymous cryptocurrency—$TRUMP coin—days before his inauguration.

“This is a classic scandal,” Holman says. “It shows the power of money over our White House and over our President, which is interesting because Trump used to claim that he was so wealthy he couldn’t be bought. Now he can be bought by a meme.” (Declining to answer specific questions about Holman’s criticisms of Trump, a White House spokesperson told Washingtonian that “President Trump’s assets are in a trust managed by his children. There are no conflicts of interest.”)

Following Holman’s car accident, he was told his recovery could take months. In mid-April, however, he left the hospital ahead of schedule, disregarding the gentle advice of friends and doctors. “I had to get the heck out of there,” he says. There was simply too much work to do.

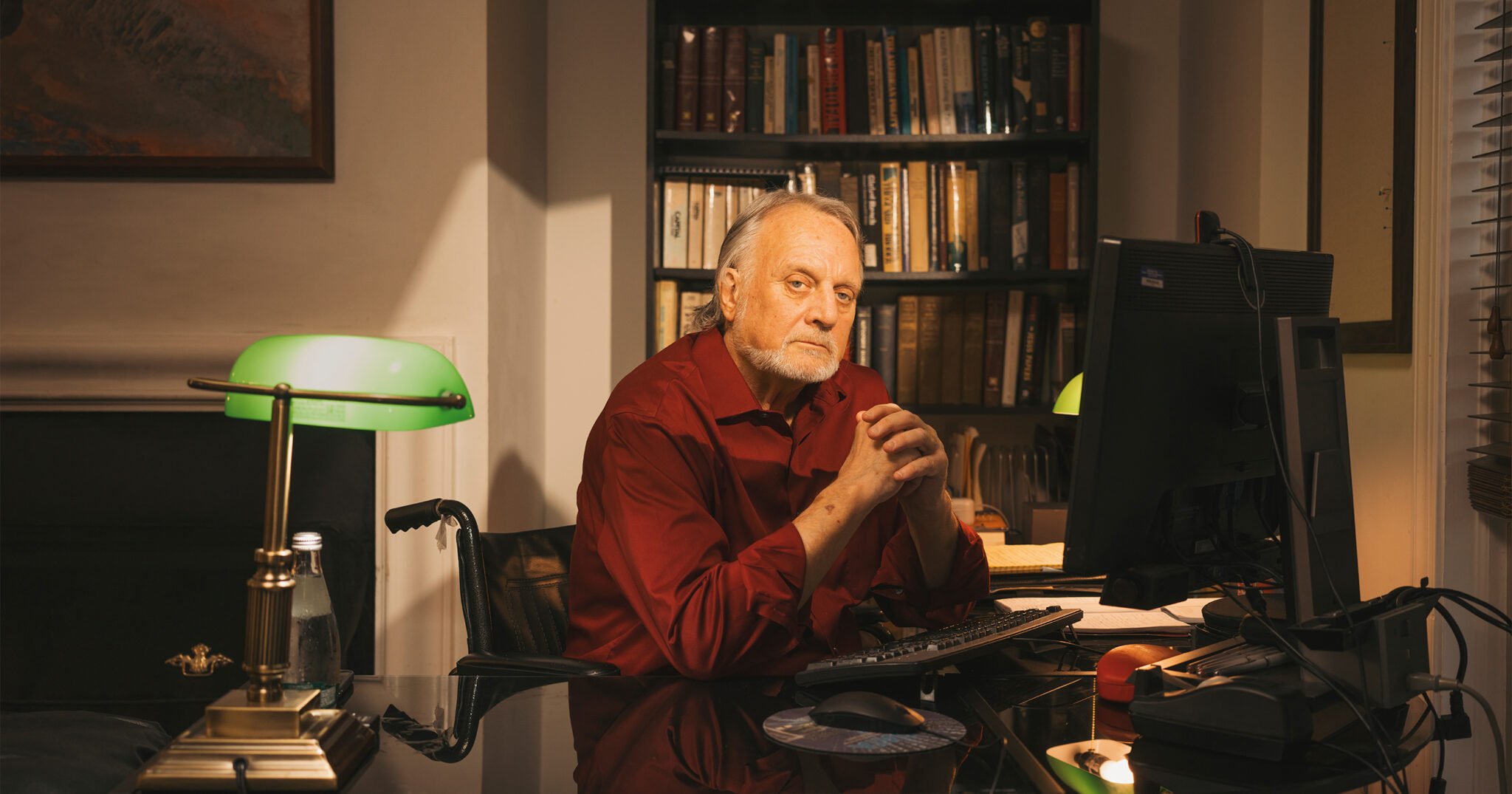

In May, I met Holman at his Capitol Hill condo. The doors on the rooms had been taken off their hinges—the better for him to squeeze his wheelchair, just barely, from the kitchen to the bedroom to the living room, which was doubling as his office.

Sitting behind a desk, Holman was busy. His phone rang constantly. He had just submitted an op-ed to the Hill arguing that Congress should ban lawmakers from trading individual stocks, to squelch potential conflicts of interest and the possibility of insider trading. He was lobbying members from both parties to support presidential-inauguration funding reforms, making the case that while the stench of buying access was particularly strong during Trump’s inauguration in January—a number of corporations and individual billionaires paid at least $1 million each for exclusive access to events and to the President’s political inner sanctum—future Presidents from either party could attempt to match or exceed the nearly $240 million that Trump’s inaugural committee raised. That’s about four times what President Joe Biden, who himself took heat for courting corporate interests, raised for his 2021 inauguration.

Because Holman still couldn’t walk, physical therapists were making house calls. (Sometimes, says Holman’s friend Michiko Bonawitz, he gets so wrapped up in his work that “he needs to be reminded to call his doctors.”) As Holman talked about his legislative goals, he sent numerous emails. Occasionally, a wince of pain broke through his smile.

“Maybe I came back too early,” he said, gingerly wheeling himself across the room. “But I fear that we’re going to lose democracy. When you look at history, no democracy has ever survived. That’s pretty motivating for me.”

A sense of high-minded urgency has long motivated reformers such as Holman. The term “goo-goo” was first used—sometimes derisively—in the late 1800s to describe candidates and groups working against corruption and old-school machine politics in places like Chicago and New York City. Over time, their ideas went national, and goo-goos were instrumental in Progressive Era efforts to increase government transparency, reduce graft, replace patronage with merit-based hiring, and otherwise professionalize civil service. Subsequent waves of reform often have come in response to scandals: Most notably, Watergate led to stricter rules around campaign finance, greater checks on executive power, and the creation of a number of government watchdogs.

Holman’s interest in good government goes back decades. Raised in Minnesota, he studied philosophy and political science at the University of Wisconsin–Madison in the late 1970s, then earned a doctorate in political science and government from the University of Southern California. He worked at the now-defunct Center for Governmental Studies, a California nonprofit that researched and recommended policy reforms, then moved across the country in 2000 to join the Brennan Center for Justice, a progressive law-and-policy institute at New York University’s law school.

Most of Holman’s work in those years was academic. He wrote books such as To Govern Ourselves: Ballot Initiatives in the Los Angeles Area and journal articles like “Access Delayed Is Access Denied: Electronic Reporting of Campaign Finance Records,” the sort of deeply researched and considered reports that provide intellectual ammunition for reformers battling in the legislative trenches. In 2002, however, Public Citizen asked him to come to Washington and shake things up in person as a government-affairs lobbyist.

At the time, Holman was nearing 50. Making the move would mean reinventing himself professionally—going from political scientist to lobbyist, from think tank to shark tank—and moving to a city he’d only visited. But Public Citizen’s offer would allow him to put theory into action, and to advocate directly for the principles he believed in. Upon arriving in DC, Holman hopped into a taxi. “The cab driver is playing NPR on the radio,” he recalls, “I said, ‘I think I can fit in here.’ ” Holman took the job.

“It turned out that it combines everything I like doing,” he says. “You teach a class, and that’s thrilling, but you don’t know if you’ve actually had an impact. With lobbying, I will know if I succeeded or not.”

Success isn’t easy. After all, Holman is a lobbyist who lobbies against other lobbyists—working to reduce their power, or that of their clients, all on behalf of policies that often put metaphorical handcuffs on the lawmakers elected to enact them.

On Capitol Hill and K Street, that makes him a rarity. In 2024, more than 13,000 registered federal lobbyists prowled the corridors of Congress and federal agencies—a 14-year high, according to the nonprofit research organization OpenSecrets. The vast majority represented corporations, trade associations, unions, or narrow-focus special-interest groups. Just a tiny fraction could ever in good faith call themselves goo-goos.

Of that sliver, few stay in the arena as long as Holman has. The hours are long, and public advocacy isn’t exactly known for its financial rewards—if you’re eyeing a nice place in Chevy Chase or thinking about sending your kids to Sidwell Friends, you’re probably getting paid to work against whatever reforms Holman is proposing. Following tours of duty at organizations like Common Cause and the Campaign Legal Center, many goo-goos exit altogether, instead finding gigs in government, electoral politics, consulting, law, or even representing corporate or special interests. “It’s great work, but it’s hard work,” says Fred Wertheimer, a longtime good-government advocate as well as founder and president of the nonpartisan government-reform group Democracy 21. “Not for everyone.”

Holman’s relationship to lawmakers is also unusual. On one hand, few members of Congress are flatly unwilling to take his calls or otherwise entertain his efforts. He’s earned the respect of Democrats and Republicans alike—in part because of his reputation for honesty and fairness, in part because the sound of his baritone voice means you might be in his sights. “Craig’s infuriated people on both sides, and he didn’t particularly care who he was offending by his work,” says former Pennsylvania Republican representative Charlie Dent, who previously worked with Holman to tighten rules around lawmakers’ and staffers’ acceptance of privately funded travel. “He was looking to do what’s right. He wasn’t looking to make friends.”

On the other hand, Holman’s aversion to cozying up to power makes him a perpetual outsider. After hours, you’re far more likely to find him at an H Street dive bar with his friends than at the downtown restaurants where lobbyists and lawmakers schmooze and make deals. Holman can’t leverage the one simple trick available to so many of his corporate cousins: campaign contributions. Ever since the Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United decision supercharged American political spending, money has dominated congressional and presidential elections in a way that makes the Watergate era look quaint.

Adjusted for inflation, the combined cost of the presidential and all congressional races in 2012 was about $8.6 billion. The 2024 election, meanwhile, cost more than $15.9 billion, with increasingly nationalized congressional races driving much of that spike, according to OpenSecrets. Viewed another way, the Federal Election Commission, which regulates and enforces the nation’s federal campaign laws, processed about 50 million campaign-finance transactions during the 2012 presidential election cycle. Twelve years later, during the 2024 cycle, it processed more than 500 million transactions, according to agency records.

“I’m glad to not be involved in that, but it is a huge disadvantage,” Holman says. “I don’t have access to money, and quite frankly, money usually wins—I’ve got to admit that. What I do have is mobilizing the public to get involved. I can once in a while beat money with that.”

Holman’s first major victory came in the mid-aughts, after a massive scandal centered on former lobbyist Jack Abramoff resulted in federal bribery or corruption convictions for Abramoff and nearly two dozen others, including White House officials, congressional staffers, and former Ohio Republican representative Bob Ney. Amid the ethical wreckage and heightened public awareness, Holman saw an opportunity. He drafted legislation to clamp down on lobbying, workshopped the text with congressional offices—writing and rewriting and writing some more—and attracted powerful lawmakers to his cause, including Republican Kentucky senator Mitch McConnell and former Nevada Democratic senator Harry Reid. That work became the Honest Leadership and Open Government Act of 2007—a laundry list of political-influence and campaign-finance reforms that bolstered lobbying-spending disclosure, corralled gift-giving, and codified criminal penalties for certain violations.

“I’ve got to draft it,” Holman says of his hands-on approach to that bill. “I can’t just offer ideas or bullet points or it’s not going to be anywhere near what I’m thinking of. And then, at the right time, you’ve got to let it go and let other people take over.”

In 2011, a producer for 60 Minutes called Holman looking for story ideas. Holman pitched an idea he’d been working on for months: banning members of Congress from trading individual stocks, via a little-known bill that was going nowhere on Capitol Hill, the Stop Trading on Congressional Knowledge Act. The producer liked the idea, and a subsequent broadcast report on congressional stock trading proved damning. Numerous lawmakers refused to speak with reporter Steve Kroft. California Democrat Nancy Pelosi, then speaker of the House, grew defensive when asked about her husband’s stock deals. During interviews outside the Capitol, several members admitted they’d never heard of the bill.

Holman’s first major victory came after the Jack Abramoff scandal, when he helped draft and attract support for the Honest Leadership and Open Government Act of 2007, legislation that clamped down on lobbying

The next year, Congress passed a version of the STOCK Act. While Holman didn’t appear in the 60 Minutes report, Public Citizen co-president Robert Weissman says it “changed the dynamics overnight. And the conditions for that happening wouldn’t have been in place if Craig had not been plowing away and pushing that rock up the hill.”

The pushing never really stops. For goo-goos, wins are rare, often partial, and seldom permanent. The STOCK Act created rules, disclosure requirements, and penalties around congressional stock trading. It did not actually ban the practice. In recent years, Holman has worked on numerous efforts that haven’t made much progress, including one to grant the US Office of Government Ethics—an independent agency that oversees executive-branch financial disclosures and conflict-of-interest rules—the power to enforce those rules.

Holman also has seen backsliding. In New Jersey, for instance, he once helped write some of the country’s strictest limits on the amount of money that companies doing business with the state can give to political parties. Two years ago, however, a major overhaul of the state’s campaign-finance laws loosened and removed those restrictions, resulting in a surge of donations. As for the aforementioned Office of Government Ethics? Earlier this year, it shrugged after Fortune reported that Trump’s Small Business Administration leader, Kelly Loeffler, retained a seven-figure investment in the parent company of Newsmax while regularly appearing on the conservative TV network to tout MAGA priorities. (An SBA spokesperson told Fortune that OGE reviewed Loeffler’s financial holdings and that she upholds “all ethics rules and requirements.”)

“This is not even a marathon, it’s aerobics in hell, a game you can’t win,” says Meredith McGehee, who has spent more than 30 years working in public-interest advocacy, most recently as executive director of Issue One, a nonprofit that advocates for campaign-finance reform. “But Craig is one of those people who figured that out and made peace with it. He gets that ‘democracy’ is a verb, something you do.”

Back in his condo, Holman is still democracy-ing. He’s a prolific multi-tasker—Oregon Democratic senator Jeff Merkley says Holman has “personally been involved with every good-government effort I take on,” including prohibiting gambling on elections and enhancing travelers’ privacy during Transportation Security Administration screening—but at this moment, he’s focused on a particular goal: finishing what the STOCK Act started.

Working the phones with the office of Rhode Island Democratic representative Seth Magaziner, Holman is pitching the Transparent Representation Upholding Service and Trust in Congress Act, which would require members—plus their spouses and dependent children—to either divest from owning individual stocks or place those assets in a blind trust while in office. With cosponsors including ultraconservative Texas Republican representative Chip Roy and ultraliberal Michigan Democratic representative Rashida Tlaib, the bill has bipartisan backing—and even support from Trump, who said in April that he would “absolutely” sign legislation banning congressional stock trading if it crossed his desk.

Holman is optimistic about the bill’s prospects. For one, House leadership from both parties recently gave it the okay to move forward. Perhaps more important, the STOCK Act’s limitations have become increasingly apparent. In recent years, dozens of representatives have violated it. Members of the House and Senate Armed Services committees actively buy and sell defense-contractor stocks; many other Congress members personally invest in industries their committees oversee. A number of representatives made a flurry of trades before and after Trump’s “Liberation Day” tariff announcements, raising questions about what they knew and whether they were trying to personally profit off executive policy changes. On Wall Street, there are two exchange-traded funds (one Democratic, one Republican) that follow congressional stock trades and allow investors to profit from them. Meanwhile, several websites and social-media accounts spit out regular updates on which lawmaker is trading what—including the “Nancy Pelosi Stock Tracker,” which follows all of Pelosi’s husband’s trades and boasts 1.1 million followers on X. (A Pelosi spokesperson recently told the Times of London that she doesn’t own stocks and has no prior knowledge or subsequent involvement in her husband’s transactions.) “This is a moment, an inflection point,” Holman says. “The comparison to what happened right before the STOCK Act is inevitable.”

Goo-goo work is “not even a marathon, it’s aerobics in hell, a game you can’t win. But Craig gets that ‘democracy’ is a verb, something you do.”

Of course, there’s no guarantee the TRUST in Congress Act, or any of several similar bills, will make it to Trump’s desk. Anything from congressional inertia to partisan bickering over details could leave it dead in the legislative water, floating listlessly alongside previously failed stock-ban bills introduced during the past two congressional sessions. Such is a goo-goo’s fate. Still, Holman wouldn’t have it any other way. Sure, the wins are affirming—but the fights and losses along the way are energizing. The nation, he says, needs someone to stand up for the little guys, people who will never trade a stock, never have the means to donate $100 or $1,000 or $1 million to a political cause, never come to Washington in the first place.

Abramoff, the disgraced former lobbyist, concurs. In the years since his scandal, he and Holman have struck up an unlikely friendship. “Some of the corruption [in Washington] breaks the law, but much of it is perfectly legal,” Abramoff told Washingtonian in an email. “That is why Craig will never be a dinosaur. He’s trying to fix a broken system—and until that is done, he will be needed.”

When Holman was hospitalized, he had plenty of time to consider his future. Should he slow down? Work part-time or consult? Clear more space for his personal passions, like astronomy and Norwegian history? Was it finally time to train a successor and let someone else push the rock toward the hilltop? Laid up in bed, newscasts playing overhead, Holman had only one answer. “I’ll never quit,” he said. “It will be someone else who tells me it’s over. Not me.” One must imagine him happy.

When Craig Holman first came to, he found himself in George Washington University Hospital hooked up to machines.

His ribs, hip, and knee were shattered. His ankle, too. He had suffered a brain bleed.

The victim of an early-March car crash—another driver struck Holman’s 2002 stick-shift Saturn after running a red light on Pennsylvania Avenue—Holman would spend a week in intensive care and three more in various hospital wards. Surgeries would follow surgeries. Much of the time, he couldn’t leave his bed without assistance.

And still he couldn’t stop thinking about Donald Trump.

For hours and hours, Holman would fixate on the newscasts emanating from the TV above his bed. Body broken, his mind seethed at what he saw as gross abuses of power by the President: firing thousands of federal workers, issuing massive tariffs, targeting law firms perceived to have worked against his political or personal interests, letting his Department of Government Efficiency run amok. Holman wasn’t happy with Congress, either, which he viewed as feckless, a legislature surrendering its constitutional clout to an overstepping executive.

“You’re sitting there, watching Trump on the news doing some obvious violation of the law, and you’re thinking, ‘I’d be filing a complaint right now if I were home!’ ” Holman says.

Of that, there’s little doubt. The 69-year-old Holman is a leading member of a peculiar Washington tribe: advocates for good government. Also known as “goo-goos,” they fight to regulate lobbying, limit the influence of money in politics, keep elected officials honest, and otherwise “drain the swamp” in the pre-Trumpian sense of the phrase.

For 23 years, Holman has been on the frontlines working as the government-affairs lobbyist for Public Citizen, the progressive nonprofit founded a half century ago by consumer advocate Ralph Nader. In the best of times, the job can feel thankless, even Sisyphean. Outnumbered and outspent, goo-goos perpetually push the rock of reform up Capitol Hill, only to be pulled back down by the stubborn gravity of wealth and self-interest.

Washington is home to a peculiar tribe: good government advocates known as “goo-goos,” who fight to regulate lobbyists, reform political-money laws, keep lawmakers honest, and “drain the swamp” in the pre-Trumpian sense of the term.

And these are not the best of times. Between an ongoing explosion of political spending and Trump’s return to the White House, goo-goos are on their back foot, confronting a new crisis almost daily. To wit: As emergency workers rescued Holman by cutting through both his car and his beloved leather jacket, the President signed an executive order establishing a government Strategic Bitcoin Reserve, never mind that Trump is heavily invested in the World Liberty Financial crypto-trading platform and launched an eponymous cryptocurrency—$TRUMP coin—days before his inauguration.

“This is a classic scandal,” Holman says. “It shows the power of money over our White House and over our President, which is interesting because Trump used to claim that he was so wealthy he couldn’t be bought. Now he can be bought by a meme.” (Declining to answer specific questions about Holman’s criticisms of Trump, a White House spokesperson told Washingtonian that “President Trump’s assets are in a trust managed by his children. There are no conflicts of interest.”)

Following Holman’s car accident, he was told his recovery could take months. In mid-April, however, he left the hospital ahead of schedule, disregarding the gentle advice of friends and doctors. “I had to get the heck out of there,” he says. There was simply too much work to do.

In May, I met Holman at his Capitol Hill condo. The doors on the rooms had been taken off their hinges—the better for him to squeeze his wheelchair, just barely, from the kitchen to the bedroom to the living room, which was doubling as his office.

Sitting behind a desk, Holman was busy. His phone rang constantly. He had just submitted an op-ed to the Hill arguing that Congress should ban lawmakers from trading individual stocks, to squelch potential conflicts of interest and the possibility of insider trading. He was lobbying members from both parties to support presidential-inauguration funding reforms, making the case that while the stench of buying access was particularly strong during Trump’s inauguration in January—a number of corporations and individual billionaires paid at least $1 million each for exclusive access to events and to the President’s political inner sanctum—future Presidents from either party could attempt to match or exceed the nearly $240 million that Trump’s inaugural committee raised. That’s about four times what President Joe Biden, who himself took heat for courting corporate interests, raised for his 2021 inauguration.

Because Holman still couldn’t walk, physical therapists were making house calls. (Sometimes, says Holman’s friend Michiko Bonawitz, he gets so wrapped up in his work that “he needs to be reminded to call his doctors.”) As Holman talked about his legislative goals, he sent numerous emails. Occasionally, a wince of pain broke through his smile.

“Maybe I came back too early,” he said, gingerly wheeling himself across the room. “But I fear that we’re going to lose democracy. When you look at history, no democracy has ever survived. That’s pretty motivating for me.”

A sense of high-minded urgency has long motivated reformers such as Holman. The term “goo-goo” was first used—sometimes derisively—in the late 1800s to describe candidates and groups working against corruption and old-school machine politics in places like Chicago and New York City. Over time, their ideas went national, and goo-goos were instrumental in Progressive Era efforts to increase government transparency, reduce graft, replace patronage with merit-based hiring, and otherwise professionalize civil service. Subsequent waves of reform often have come in response to scandals: Most notably, Watergate led to stricter rules around campaign finance, greater checks on executive power, and the creation of a number of government watchdogs.

Holman’s interest in good government goes back decades. Raised in Minnesota, he studied philosophy and political science at the University of Wisconsin–Madison in the late 1970s, then earned a doctorate in political science and government from the University of Southern California. He worked at the now-defunct Center for Governmental Studies, a California nonprofit that researched and recommended policy reforms, then moved across the country in 2000 to join the Brennan Center for Justice, a progressive law-and-policy institute at New York University’s law school.

Most of Holman’s work in those years was academic. He wrote books such as To Govern Ourselves: Ballot Initiatives in the Los Angeles Area and journal articles like “Access Delayed Is Access Denied: Electronic Reporting of Campaign Finance Records,” the sort of deeply researched and considered reports that provide intellectual ammunition for reformers battling in the legislative trenches. In 2002, however, Public Citizen asked him to come to Washington and shake things up in person as a government-affairs lobbyist.

At the time, Holman was nearing 50. Making the move would mean reinventing himself professionally—going from political scientist to lobbyist, from think tank to shark tank—and moving to a city he’d only visited. But Public Citizen’s offer would allow him to put theory into action, and to advocate directly for the principles he believed in. Upon arriving in DC, Holman hopped into a taxi. “The cab driver is playing NPR on the radio,” he recalls, “I said, ‘I think I can fit in here.’ ” Holman took the job.

“It turned out that it combines everything I like doing,” he says. “You teach a class, and that’s thrilling, but you don’t know if you’ve actually had an impact. With lobbying, I will know if I succeeded or not.”

Success isn’t easy. After all, Holman is a lobbyist who lobbies against other lobbyists—working to reduce their power, or that of their clients, all on behalf of policies that often put metaphorical handcuffs on the lawmakers elected to enact them.

On Capitol Hill and K Street, that makes him a rarity. In 2024, more than 13,000 registered federal lobbyists prowled the corridors of Congress and federal agencies—a 14-year high, according to the nonprofit research organization OpenSecrets. The vast majority represented corporations, trade associations, unions, or narrow-focus special-interest groups. Just a tiny fraction could ever in good faith call themselves goo-goos.

Of that sliver, few stay in the arena as long as Holman has. The hours are long, and public advocacy isn’t exactly known for its financial rewards—if you’re eyeing a nice place in Chevy Chase or thinking about sending your kids to Sidwell Friends, you’re probably getting paid to work against whatever reforms Holman is proposing. Following tours of duty at organizations like Common Cause and the Campaign Legal Center, many goo-goos exit altogether, instead finding gigs in government, electoral politics, consulting, law, or even representing corporate or special interests. “It’s great work, but it’s hard work,” says Fred Wertheimer, a longtime good-government advocate as well as founder and president of the nonpartisan government-reform group Democracy 21. “Not for everyone.”

Holman’s relationship to lawmakers is also unusual. On one hand, few members of Congress are flatly unwilling to take his calls or otherwise entertain his efforts. He’s earned the respect of Democrats and Republicans alike—in part because of his reputation for honesty and fairness, in part because the sound of his baritone voice means you might be in his sights. “Craig’s infuriated people on both sides, and he didn’t particularly care who he was offending by his work,” says former Pennsylvania Republican representative Charlie Dent, who previously worked with Holman to tighten rules around lawmakers’ and staffers’ acceptance of privately funded travel. “He was looking to do what’s right. He wasn’t looking to make friends.”

On the other hand, Holman’s aversion to cozying up to power makes him a perpetual outsider. After hours, you’re far more likely to find him at an H Street dive bar with his friends than at the downtown restaurants where lobbyists and lawmakers schmooze and make deals. Holman can’t leverage the one simple trick available to so many of his corporate cousins: campaign contributions. Ever since the Supreme Court’s 2010 Citizens United decision supercharged American political spending, money has dominated congressional and presidential elections in a way that makes the Watergate era look quaint.

Adjusted for inflation, the combined cost of the presidential and all congressional races in 2012 was about $8.6 billion. The 2024 election, meanwhile, cost more than $15.9 billion, with increasingly nationalized congressional races driving much of that spike, according to OpenSecrets. Viewed another way, the Federal Election Commission, which regulates and enforces the nation’s federal campaign laws, processed about 50 million campaign-finance transactions during the 2012 presidential election cycle. Twelve years later, during the 2024 cycle, it processed more than 500 million transactions, according to agency records.

“I’m glad to not be involved in that, but it is a huge disadvantage,” Holman says. “I don’t have access to money, and quite frankly, money usually wins—I’ve got to admit that. What I do have is mobilizing the public to get involved. I can once in a while beat money with that.”

Holman’s first major victory came in the mid-aughts, after a massive scandal centered on former lobbyist Jack Abramoff resulted in federal bribery or corruption convictions for Abramoff and nearly two dozen others, including White House officials, congressional staffers, and former Ohio Republican representative Bob Ney. Amid the ethical wreckage and heightened public awareness, Holman saw an opportunity. He drafted legislation to clamp down on lobbying, workshopped the text with congressional offices—writing and rewriting and writing some more—and attracted powerful lawmakers to his cause, including Republican Kentucky senator Mitch McConnell and former Nevada Democratic senator Harry Reid. That work became the Honest Leadership and Open Government Act of 2007—a laundry list of political-influence and campaign-finance reforms that bolstered lobbying-spending disclosure, corralled gift-giving, and codified criminal penalties for certain violations.

“I’ve got to draft it,” Holman says of his hands-on approach to that bill. “I can’t just offer ideas or bullet points or it’s not going to be anywhere near what I’m thinking of. And then, at the right time, you’ve got to let it go and let other people take over.”

In 2011, a producer for 60 Minutes called Holman looking for story ideas. Holman pitched an idea he’d been working on for months: banning members of Congress from trading individual stocks, via a little-known bill that was going nowhere on Capitol Hill, the Stop Trading on Congressional Knowledge Act. The producer liked the idea, and a subsequent broadcast report on congressional stock trading proved damning. Numerous lawmakers refused to speak with reporter Steve Kroft. California Democrat Nancy Pelosi, then speaker of the House, grew defensive when asked about her husband’s stock deals. During interviews outside the Capitol, several members admitted they’d never heard of the bill.

Holman’s first major victory came after the Jack Abramoff scandal, when he helped draft and attract support for the Honest Leadership and Open Government Act of 2007, legislation that clamped down on lobbying

The next year, Congress passed a version of the STOCK Act. While Holman didn’t appear in the 60 Minutes report, Public Citizen co-president Robert Weissman says it “changed the dynamics overnight. And the conditions for that happening wouldn’t have been in place if Craig had not been plowing away and pushing that rock up the hill.”

The pushing never really stops. For goo-goos, wins are rare, often partial, and seldom permanent. The STOCK Act created rules, disclosure requirements, and penalties around congressional stock trading. It did not actually ban the practice. In recent years, Holman has worked on numerous efforts that haven’t made much progress, including one to grant the US Office of Government Ethics—an independent agency that oversees executive-branch financial disclosures and conflict-of-interest rules—the power to enforce those rules.

Holman also has seen backsliding. In New Jersey, for instance, he once helped write some of the country’s strictest limits on the amount of money that companies doing business with the state can give to political parties. Two years ago, however, a major overhaul of the state’s campaign-finance laws loosened and removed those restrictions, resulting in a surge of donations. As for the aforementioned Office of Government Ethics? Earlier this year, it shrugged after Fortune reported that Trump’s Small Business Administration leader, Kelly Loeffler, retained a seven-figure investment in the parent company of Newsmax while regularly appearing on the conservative TV network to tout MAGA priorities. (An SBA spokesperson told Fortune that OGE reviewed Loeffler’s financial holdings and that she upholds “all ethics rules and requirements.”)

“This is not even a marathon, it’s aerobics in hell, a game you can’t win,” says Meredith McGehee, who has spent more than 30 years working in public-interest advocacy, most recently as executive director of Issue One, a nonprofit that advocates for campaign-finance reform. “But Craig is one of those people who figured that out and made peace with it. He gets that ‘democracy’ is a verb, something you do.”

Back in his condo, Holman is still democracy-ing. He’s a prolific multi-tasker—Oregon Democratic senator Jeff Merkley says Holman has “personally been involved with every good-government effort I take on,” including prohibiting gambling on elections and enhancing travelers’ privacy during Transportation Security Administration screening—but at this moment, he’s focused on a particular goal: finishing what the STOCK Act started.

Working the phones with the office of Rhode Island Democratic representative Seth Magaziner, Holman is pitching the Transparent Representation Upholding Service and Trust in Congress Act, which would require members—plus their spouses and dependent children—to either divest from owning individual stocks or place those assets in a blind trust while in office. With cosponsors including ultraconservative Texas Republican representative Chip Roy and ultraliberal Michigan Democratic representative Rashida Tlaib, the bill has bipartisan backing—and even support from Trump, who said in April that he would “absolutely” sign legislation banning congressional stock trading if it crossed his desk.

Holman is optimistic about the bill’s prospects. For one, House leadership from both parties recently gave it the okay to move forward. Perhaps more important, the STOCK Act’s limitations have become increasingly apparent. In recent years, dozens of representatives have violated it. Members of the House and Senate Armed Services committees actively buy and sell defense-contractor stocks; many other Congress members personally invest in industries their committees oversee. A number of representatives made a flurry of trades before and after Trump’s “Liberation Day” tariff announcements, raising questions about what they knew and whether they were trying to personally profit off executive policy changes. On Wall Street, there are two exchange-traded funds (one Democratic, one Republican) that follow congressional stock trades and allow investors to profit from them. Meanwhile, several websites and social-media accounts spit out regular updates on which lawmaker is trading what—including the “Nancy Pelosi Stock Tracker,” which follows all of Pelosi’s husband’s trades and boasts 1.1 million followers on X. (A Pelosi spokesperson recently told the Times of London that she doesn’t own stocks and has no prior knowledge or subsequent involvement in her husband’s transactions.) “This is a moment, an inflection point,” Holman says. “The comparison to what happened right before the STOCK Act is inevitable.”

Goo-goo work is “not even a marathon, it’s aerobics in hell, a game you can’t win. But Craig gets that ‘democracy’ is a verb, something you do.”

Of course, there’s no guarantee the TRUST in Congress Act, or any of several similar bills, will make it to Trump’s desk. Anything from congressional inertia to partisan bickering over details could leave it dead in the legislative water, floating listlessly alongside previously failed stock-ban bills introduced during the past two congressional sessions. Such is a goo-goo’s fate. Still, Holman wouldn’t have it any other way. Sure, the wins are affirming—but the fights and losses along the way are energizing. The nation, he says, needs someone to stand up for the little guys, people who will never trade a stock, never have the means to donate $100 or $1,000 or $1 million to a political cause, never come to Washington in the first place.

Abramoff, the disgraced former lobbyist, concurs. In the years since his scandal, he and Holman have struck up an unlikely friendship. “Some of the corruption [in Washington] breaks the law, but much of it is perfectly legal,” Abramoff told Washingtonian in an email. “That is why Craig will never be a dinosaur. He’s trying to fix a broken system—and until that is done, he will be needed.”

When Holman was hospitalized, he had plenty of time to consider his future. Should he slow down? Work part-time or consult? Clear more space for his personal passions, like astronomy and Norwegian history? Was it finally time to train a successor and let someone else push the rock toward the hilltop? Laid up in bed, newscasts playing overhead, Holman had only one answer. “I’ll never quit,” he said. “It will be someone else who tells me it’s over. Not me.” One must imagine him happy.

This article appears in the August 2025 issue of Washingtonian.