Chinatown is shrinking, as anyone who’s seen all the shuttered storefronts along H Street, Northwest, has noticed. Many of the longtime Chinese businesses have closed, and American chains have moved in, serving burgers or coffee beneath neon signs stamped with Chinese translations. Most recently, Full Kee Restaurant and Gao Ya Hair Salon closed as developers moved forward with plans to build a Marriott hotel on the lot. Many residents have been priced out of the once-bustling neighborhood, which was home to about 3,000 Chinese residents in 2010. Now that number is closer to 350.

But while DC’s Chinatown feels much diminished, residents and business owners still consider the area a place of connection and culture that’s worth protecting. About ten AAPI-owned small businesses remain, weathering the changes in the neighborhood. There are still spots to order an authentic meal, chat with your cashier in Mandarin or Cantonese, or find a traditional remedy for a cough. To get a sense of what’s being lost, we spent time with people behind four remaining establishments, some of whom spoke in Mandarin. (Responses have been translated.)

—Katie Doran

De Zhi Co.

602 H St., NW

Since 2012

De Zhi Co. is a spot you’ll find only if you know where to look. The small second-floor shop doesn’t even have a website, but it does offer one of the best selections of traditional Chinese medicinal goods in DC. Its shelves are crowded with fragrant collections of Chinese herbs, teas, snacks, and ingredients. But business is slow, according to owner Liu Chan Quiang. “It’s mostly local people, friends, neighbors who shop here,” he says, speaking in Mandarin. “Chinatown used to be livelier. Since Covid, there have been fewer tourists, less people, and less business.”

Liu emigrated from China in 1992, staying in San Francisco for a year before settling in the Washington area. He opened De Zhi Co. 13 years ago. The store is named for Liu’s grandfather, Liu De Zhi, who practiced traditional Chinese medicine in Guangzhou. Some of its bestselling products were invented by the store’s namesake, Liu tells me proudly, including a cough medicine and an herbal tea.

But none of that is enough to counteract the challenges of running a business in Chinatown. De Zhi Co.’s upstairs location doesn’t help, either. Liu points to a shelf with boxes and boxes of mooncakes. “Other stores can sell these for $26 a box, but we can only sell it for $20 or $22. With our location, there’s just no other way.”

Liu has watched as friends and peers moved away from Chinatown in the face of financial pressures. “Immigrants with businesses here have moved outside Chinatown and DC, mostly because buildings and rent are so expensive,” he says. “Those who leave Chinatown do not come back. Bit by bit, immigrants have left.” Liu himself used to live in Chinatown, closer to his store, but now lives in Arlington. “Development around us is getting bigger and bigger,” he says, “but Chinatown is getting smaller and smaller.”

—Katie Doran

Joy Luck House

748 Sixth St., NW

Since 1993

The shrimp wonton noodle soup at Joy Luck House is one of owner June Lin’s favorite dishes on the menu. “Travelers will often say our wonton noodle soup reminds them of their hometown and Guangzhou,” Lin says proudly in Mandarin. “To hear them say that it has the taste of their hometown makes me quite happy.”

But some other Joy Luck House dishes are meant to appeal more to non-Chinese diners than those looking for an authentic meal, Lin says. On the menu, you’ll find an array of congee and soup noodles—peak Chinese comfort foods—next to westernized dishes like General Tso’s chicken, beef broccoli, and orange chicken. Those are meant for an American customer base in a city—and, increasingly, a Chinatown—that isn’t particularly Chinese.

Lin moved to Chinatown, where she still lives, in 2005 and has watched the neighborhood’s transformation over the past two decades. “Stores that sell things representing Chinese culture have all closed,” she says. “Now it’s just foreign stores. DC Chinatown was small to begin with, without a lot of people or Chinese people. But now what’s left is even smaller, with just a lot of elderly people.”

Joy Luck House opened in 1993, and Lin took it over in 2019. The restaurant struggled through the pandemic, and business hasn’t really recovered. “Chinatown used to be a tourist destination,” she says, “but now it’s not. Business now is not very good.” And prices for ingredients like eggs and beef are high. “It’s hard, but I know it’s hard for everyone. It’s not just me.” Joy Luck House’s lease is up in September 2026, and Lin is already talking with the landlord, trying to extend it. “Obviously, I hope that we can keep running our business,” she says. “But we need to be able to survive, too. If not, we’d have no choice but to close.”

As Lin points out, the presence of Chinese businesses and restaurants is what makes Chinatown a cultural center rather than just a name, and she thinks it’s important not only to save current businesses but to attract new ones. “I hope Chinatown can become more beautiful,” she says. “Don’t let it look more and more rundown and desolate.”

—Katie Doran

Tony Cheng

619 H St., NW

Since 1986

Tony Cheng has been a fixture of the neighborhood for so long that he jokingly refers to himself as the mayor of Chinatown. The seafood restaurant that he and his wife, Julie, operate together opened in 1986. At 77 years old, Cheng thinks work keeps him happy and healthy. “I don’t want to stay at home,” he says. “I live in Virginia—but Chinatown is home.”

Cheng left Hong Kong for DC when he was 17. Just a few years later, he achieved his dream of opening a Chinese restaurant, initially in New York. He married Julie, and they returned to DC in 1971. The couple opened a place in Alexandria and then on I Street, Northwest. The latter location, Washington’s first Szechuan restaurant, is now closed but was a soaring success in the late ’70s and ’80s.

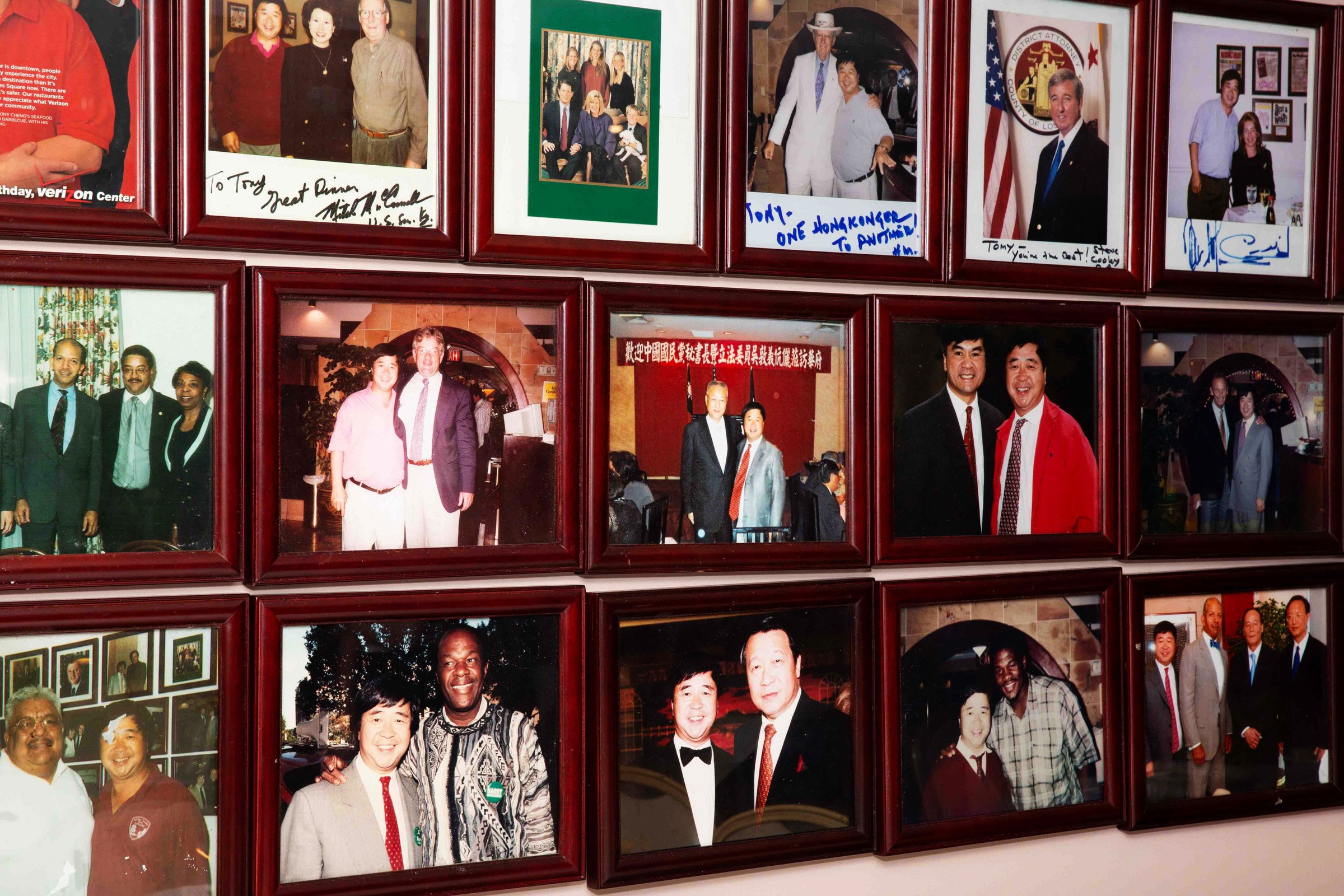

The restaurant has served plenty of VIPs over the years, including Marion Barry and Mike Tyson. Cheng has shaken hands with four American Presidents, he says, and Jimmy Carter was so enamored with his meals that Cheng was invited to cater a dinner at the White House in 1981. He keeps a handful of Carter memorabilia at the restaurant, including a signed and framed copy of the evening’s menu.

But the Chengs’ heyday in Chinatown is long over. The couple no longer own the building they occupy, following a bankruptcy filing and foreclosure sale last year. Tony now rents the upstairs floor space for his seafood restaurant, while the ground-floor storefront is empty, having previously been home to Cheng’s Mongolian barbecue spot, which went out of business during the pandemic. Earlier this year, city officials shuttered Tony Cheng’s, alleging that it owed more than $500,000 in back taxes. The debt was resolved, and the restaurant reopened in June.

“Everybody’s scared they will be forced to close,” Cheng said recently over the quiet hum of a disappointing lunch crowd. As with most Chinatown business owners, he’s been hurt by the decline in visitors and office workers. But Cheng plans to stick around. “I work very hard, my wife works very hard,” he says. “That’s how we plan to survive. I have been here for almost half a century. Everybody knows me here. I want to fight.”

—Sam Cabral

Chinatown Liquor

602 H St., NW

Since 1987

For nearly four decades, this little store has sold a wide range of beverages, from beer and Scotch to baijiu and sake. Chinatown Liquor stays afloat thanks to a steady trickle of customers, but business isn’t what it once was. “The pandemic was the worst,” says manager John Kwon. “We did a tenth of the business. It was a ghost town, nobody around, no cars passing by. Now it’s gotten a little better, but still there aren’t too many [office workers] around and a lot of other businesses have closed. The area has gotten so expensive, and all the developers have bought up a lot of these buildings.”

Though Chinatown relies on tourists for much of its business, the liquor store has a loyal base of locals. “We have a really good relationship with customers,” Kwon says. “I usually go by first names, so it’s like friends coming in.” Sure enough, while I was there recently, store clerk Cindy Yu wished one regular a happy birthday.

Kwon works seven days a week and hasn’t had a vacation in a long time, but rising costs and low foot traffic mean no money to hire more employees. “A lack of business—there’s nothing you can do about it,” he says. “Just got to deal with it until it gets better.”

—Sam Cabral

This article appears in the October 2025 issue of Washingtonian.