“Tell your wife goodbye,”

said the nurse. Mayowa Adelekun waved from behind a window as a gurney holding his wife, Erin, was hoisted into a medevac helicopter. Rotors roaring, the aircraft lifted off from the roof of Anne Arundel Medical Center in Annapolis and headed 30 miles west to MedStar Washington Hospital Center, where a trauma team was waiting.

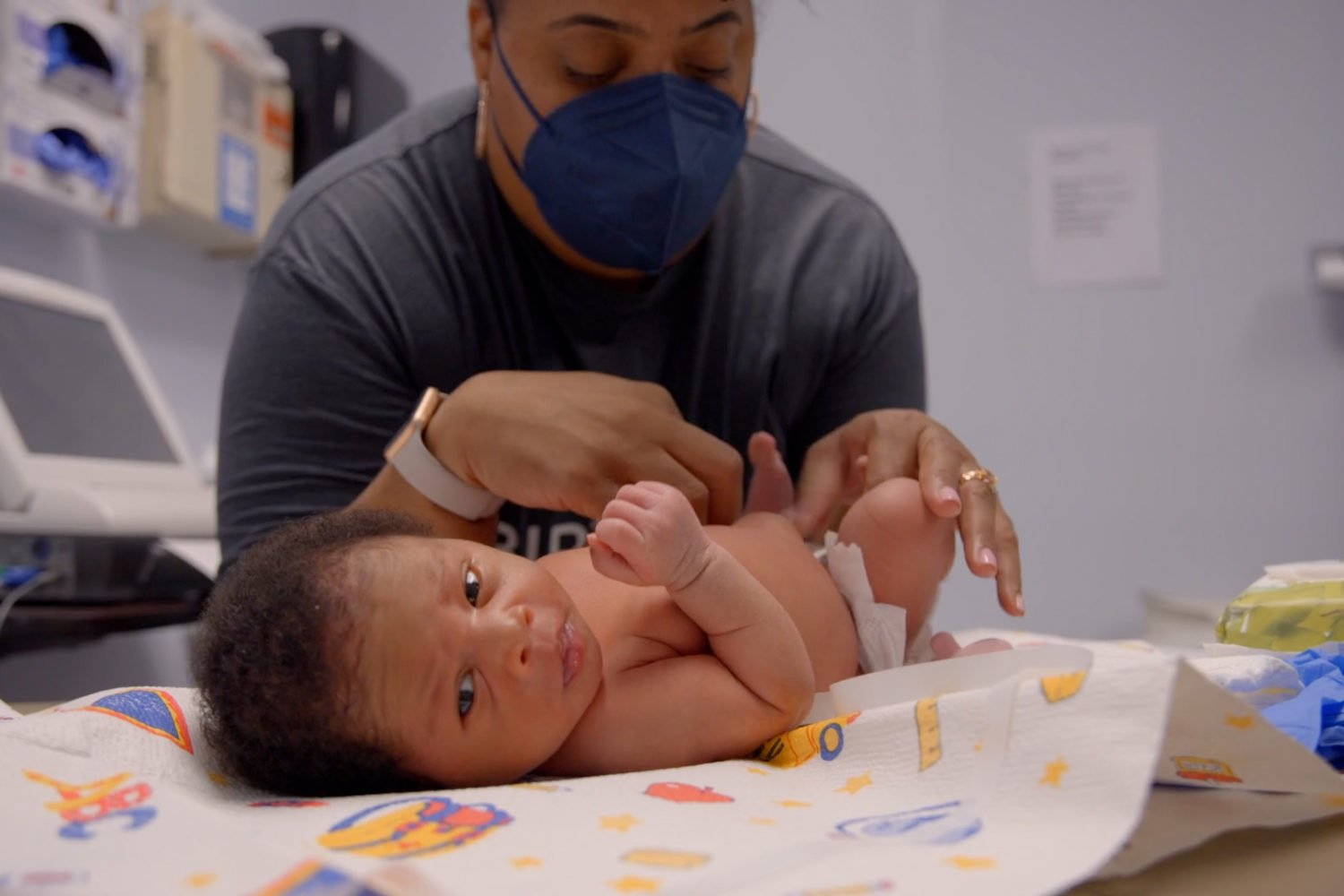

Nine days earlier, Mayowa and Erin had been giddy with joy at the birth of their daughter, Adenike. A post-delivery photo taken in this same hospital shows her resting on Erin’s chest, swaddled in a blanket and wearing a pink cap. Mom beams from under a puffy hair cover. Daddy leans awkwardly into the shot, his facemask pulled down to show his proud grin.

Mother and daughter had gone home healthy—but now Erin had returned with a life-threatening stroke. As the helicopter receded into the distance, Mayowa didn’t know if he was saying goodbye for the moment or goodbye forever. Doctors didn’t know, either. Only one thing was certain: Mayowa wasn’t allowed to ride along, nor to enter the next hospital. It was August 2020, six months into the coronavirus pandemic. No vaccines were available yet. Covid had already killed thousands of Americans. Hospitals were overcrowded and had banned visitors to limit its spread.

Sobbing in fear and frustration, Mayowa headed home, where his mother-in-law was waiting with Adenike and his two older children. From his car, he called MedStar Washington. The person on the phone told Mayowa they hadn’t received the body yet. Those words—the body—gave him an icy chill.

Mayowa, whose family calls him Mayo, and Erin Calloway met on the Plenty of Fish app. Online dating wasn’t her thing, but a friend had found a partner there and persuaded Erin to try it, just for a week. Erin got lots of messages from men who hadn’t bothered to read her profile, and she was ready to quit when she saw one from Mayo. He shared her passion for Game of Thrones, and she liked his sense of humor enough to meet him at Dave & Buster’s—a noisy cross between a diner and a video-game arcade that offered plenty of distractions if the date didn’t go well.

“We just clicked,” Erin says. “We started hanging out every day, and on a car trip to Atlanta we decided to get married.”

They did, just six months after that first date. Mayo fell in love with Erin’s “good heart” and “listening ear.”

“We were destined to be together,” he says.

Three months before the couple met, Erin’s sister, Betsy, had died from kidney failure at age 36. The two were very close, and Erin had previously given Betsy one of her kidneys, a gift that kept her sister alive for an extra decade. “Betsy passing made me think life is short and you just need to take chances,” Erin says. Taking a chance on Mayo, she adds, “paid off because we’ve been happily married for eight-plus years.”

At first, both of their families—Erin’s in Maryland and Mayo’s in Nigeria—wondered if their union would last. The newlyweds threw themselves into family life in Bowie with Mayo’s two young children from a previous marriage. Erin worked for a financial company; Mayo sold cars and, when sales were slow, did rideshare and delivery gig work. He went back to school at a community college. The family moved to Richmond for a few years after Erin got a promotion, but they were happy to return to Maryland when the opportunity arose.

By that time, Erin was pregnant. The older kids were excited: Mayo’s son wanted a boy, and his little sister was pulling for a girl. At 38, Erin was considered old to be a first-time mother. Yet while health workers described her pregnancy as “geriatric,” she found it to be easy and uneventful. Covid was a source of stress, but she and Mayo were careful. Both tested negative right before Adenike’s delivery date. She was born by cesarean section at Anne Arundel Medical Center on July 24, 2020.

C-section recovery usually takes about six weeks, and most women spend two to four nights in the hospital. Because of Covid, Erin’s care team told her she’d be much safer at home and discharged her after two nights. When Erin mentioned she had a headache, a doctor recommended she take Tylenol, which eased the pain. But the Sunday after she went home, eight days later, her headache returned—stronger than before. Exhausted from her surgery, lack of sleep, and constant breastfeeding, Erin made a mental note: If she still felt bad on Monday, she’d call the doctor.

The next morning, August 3, Erin woke up with the worst headache of her life. The doctor’s office wasn’t open yet, so Mayo suggested she rest a little longer while he made her some tea and Nigerian custard. When he called out to say breakfast was ready, Erin tried to answer, but no words came out—all she could utter was “Arr, arr, arr.” She stood up shakily and groped her way down the stairs of their townhouse and into the kitchen, where Mayo was waiting. Suddenly, her right arm went limp. At that moment, they both realized she was having a stroke.

Mayo got Erin into the car and raced to the hospital. Terrified, he tried to act calm, reassuring his wife that everything was going to be okay. Sitting in the back seat, Erin was overwhelmed by mute panic: What would happen to Adenike if she didn’t survive? She desperately needed to tell Mayo that only two pouches of pumped breast milk were in the refrigerator. Baby formula would work, but did he know how to prepare it? She needed to tell him so many things.

Arriving at Anne Arundel Medical Center, Erin was rushed to the imaging department. She had a seizure on the MRI table. Hoping to prevent additional damage to her brain, doctors put her into an induced coma before having her airlifted to MedStar Washington Hospital Center.

A few hours later, MedStar neurosurgeon Jeffrey Mai called to tell Mayo that his wife needed an emergency procedure. “We’ll try our best,” Dr. Mai told Mayo, “but I cannot promise anything about the outcome.”

While strokes after giving birth are rare, they happen more than you might think. According to the American Heart Association and the American Stroke Association, 30 of 100,000 pregnant women will experience one. Compared with the incidence in non-pregnant women, stroke risk is three times greater during the third trimester and the first three months postpartum. The risk is higher still for African American women, those who deliver via cesarean section, and women who experience high blood pressure during pregnancy.

Strokes occur when blood flow to the brain is interrupted. They’re the fifth-leading cause of death in America. The vast majority are ischemic, which means a blood vessel is blocked. Erin’s stroke, however, was hemorrhagic: Burst vessels on both sides of her brain were pouring blood into her cranium, squeezing her brain into a shape it wasn’t meant to be.

Mai wanted to avoid cutting into Erin’s brain, so he installed a tube inside her skull to drain blood and relieve pressure. The medical team chilled her whole body, a strategy for reducing brain activity and limiting damage. But hours later, Erin’s blood pressure was still critically elevated. A high-risk surgery was her only hope. Mai removed a large piece of Erin’s skull in order to reduce the ongoing pressure on her brain, and he placed that “flap” of skull in her abdomen, the safest place to store cranial bone until it can be returned to its place of origin—assuming the patient survives.

Two days later, Mai called Mayo at 9 pm. He had arranged for Mayo to visit his wife, despite the pandemic lockdown. The doctor feared Erin might not make it through the night. Arriving at the intensive-care unit, Mayo was shocked to see his unconscious wife surrounded by machines and monitors. Her face was obscured by ventilation equipment. A drainage tube snaked out of her heavily bandaged head. A tangle of lines and cables connected her to IV drips and monitors.

Mayo reached for Erin’s hand. He said prayers. He sang to her for hours. There was no response. Mayo believed that Erin’s future was in God’s hands—he could only hope that prayers would make a difference. He did not say goodbye.

When Erin first regained consciousness, she thought she was dreaming. Despite dazzling bright light, she could barely make out foggy images of people in hazmat suits floating around her. She now had Covid and pneumonia—putting her health in even more danger—and didn’t understand anything the suited people were telling her.

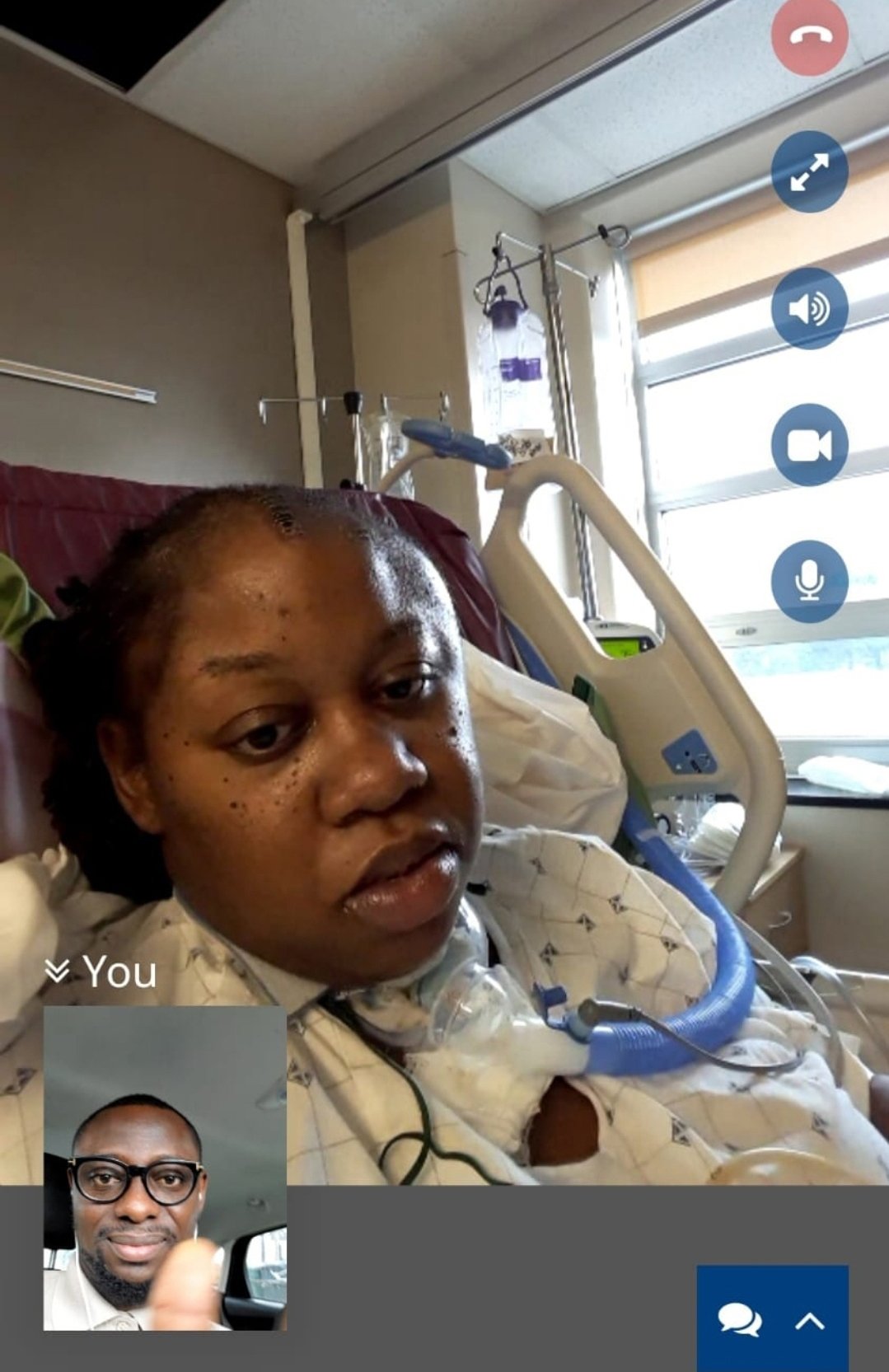

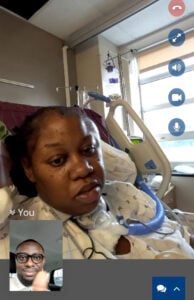

On a video call that Erin’s caregivers set up, Mayo told his wife she’d had a stroke, that her survival was miraculous, and that she’d been unconscious for almost a month. Adenike, he reassured her, was fine. That helped to hear. Only Erin couldn’t speak. She was immobile, tethered to equipment. Her head was surrounded by cushioning to protect her skull. Her right side was paralyzed, and her only way to communicate was by using her left hand to point to pictures. It took several people to move her into a wheelchair, and she had to wear a protective helmet anytime she got out of bed.

Erin didn’t yet understand how fortunate she was. More than a third of people who suffer a cerebral hemorrhagic stroke like hers don’t survive the first month. Many others don’t make it through the first year. Researchers aren’t entirely sure why pregnant and postpartum women are more susceptible to bleeding in the brain—high blood pressure and the fact that the heart has to work harder before and after birth may increase risk—but their numbers have been increasing over the past few decades.

After 29 days in the ICU, Erin was moved next door to National Rehabilitation Hospital. The transition was joyful—I’m still alive!—but the road ahead was daunting. She’d have to relearn how to walk and talk while also working to get her paralyzed right arm, hand, leg, and foot functioning again. Her rehab team crowned her with a new helmet, bejeweled with multicolored glass gemstones. She was still in bed when her physical therapy began, and she wasn’t happy when the therapist raised her fully upright and batted a balloon at her. It took a week for Erin to move her arms enough to start batting it back. She was fitted with a brace on her unresponsive right foot and ankle and was hooked up to a pulley system to help her get up and down into a chair. A month and a half after her admission, she finally got out of the chair on her own and took five steps using a four-point cane.

Before the stroke, Erin was right-side dominant, but now her right hand was balled up in an unresponsive fist. She couldn’t lift her right arm, and her right leg wasn’t cooperating, either. While working to regain some function on that side, Erin also had to learn to do everything left-handed. At the same time, she had to relearn how to talk. She suffered from global aphasia, a severe language disorder caused by brain injury.

Erin’s first goal was to learn to say the names of family and friends. A group of friends made a banner with photos and names, which a speech therapist hung in her room. Erin studied it every day. With Covid protocols, Erin was allowed to have a single adult visitor each week, usually Mayo, arriving with cellphone photos of Adenike. In September, he arranged a group video call with the people in the pictures for Erin’s birthday, and she managed to greet everyone by name—including Adenike, whose name was the hardest for her to say.

“Words can’t describe what it meant to me to have that call,” Erin says. “Everyone must have thought I was a zombie because I made no expressions. It may have looked like I was out of it, but inside I was thanking God for my family and friends.”

Erin was discharged after three months. When she got home, Adenike was crying. Still wearing a helmet to protect the soft side of her head, Erin settled on the sofa, holding her baby to her chest.

“She remembered I was her mother,” Erin says. The crying stopped.

For most stroke patients, going from hospital to home is the biggest challenge. “Reality sets in,” says Dr. Emma Nally, who specializes in brain injury and stroke recovery at National Rehabilitation Hospital. In addition to dealing with ongoing physical symptoms, patients and their families have to schedule medical appointments, deal with health insurance, and handle tasks as simple as getting to rehab—which isn’t so simple when a patient can’t walk or drive themselves. For postpartum patients such as Erin, the care and feeding of an infant can add more stress.

For a brief time after Erin came home, her family had a home health aide—but mostly it fell to Mayo to care for everyone: two school-age children with their activities and homework, three-month-old Adenike, and Erin, who needed almost as much attention as their infant daughter. Each morning, he’d get the baby fed and dressed and the older children ready for school. Then he’d help Erin bathe, dress, and go downstairs, where she’d stay, working several days a week with therapists who came to the house, until Mayo returned from work. Erin’s mother would help out, but she was in her seventies and couldn’t do any heavy lifting. Meanwhile, Erin was unable to pick Adenike up or change her diapers—not with only one functional hand—so Mayo had to take the baby to daycare.

Overnight, Mayo would change Adenike’s diapers and help Erin get to the bathroom and back. He never got a good night’s sleep and was perpetually exhausted. When the pest-control company where Mayo worked couldn’t give him a flexible schedule, he had to quit. The family relied on disability coverage from Erin’s employer.

Nally says Erin is lucky: She has a strong family support network and access to excellent care in the Washington region. (Stroke patients in rural areas, by contrast, have far fewer options nearby.) Erin and Mayo tried to stay positive despite all the stress—but each could see the frustration and worry in the other’s face. Mayo tried to take everything one day at a time, believing God was in control and relying on a family friend who is a neurologist to explain what Erin was going through. Still, he struggled with all of his new responsibilities and had no clear vision of what the future held. Erin had been the family’s caregiver, the “fun one” who’d organized everything for everyone. Now she was relying on others, and felt awful about it.

Early in her recovery, Erin thought she might wake up one day and be back to normal. She saw a doctor who evaluated her for Social Security disability benefits. He told her she’d never work again. But I’m just 39 years old, she said. She has a business degree from Morgan State University and a master’s in communications from Georgetown and had a successful career before the stroke.

The doctor shook his head—nope, not going to happen.

“That doctor lit a fire in me,” Erin says.

Determined to reclaim her independence, she set a goal: to reach the best version of “normal” she could achieve. She progressed from using a walker to taking short, unassisted walks outside the couple’s Upper Marlboro home, with Mayo watching nervously from inside. Nine months after her stroke, she had surgery to repair her skull. Soon after, her headaches subsided, and Erin—who loves to laugh—was able to do so without pain. Her helmet was history.

Regaining speech was harder. A vivacious extrovert, Erin was “embarrassed to talk.” When she tried, listeners often turned to Mayo to ask what she’d said. That hurt. Erin found an app that allowed her to practice speaking privately. She connected with the Stroke Comeback Center in Vienna, a nonprofit that offers affordable programs for stroke survivors and their families. The center has professional counselors on staff, but much of the support it provides comes from survivors helping one another. At first, Erin was silent in group conversations there—but over time she began joining in, and even worked on the center’s podcast.

Gaining confidence, she posted about her recovery on Instagram with the handle @Stroke.Mama. Erin found this therapeutic, a way to encourage herself and others. Mayo took the photos and videos for her posts, which are full of self-deprecating humor. She attracted hundreds of followers, who chimed in with comments like “You are an inspiration to me” and “You are unstoppable, girl.” Eventually, the American Heart Association of Greater Washington recognized Erin’s social-media feed, giving her a “Leader of Impact” award for her willingness to show her struggles and encourage other survivors to advocate for themselves.

Erin had her car modified to accommodate the stiffness on her right side: The gas pedal was moved to the left, and a knob was added to the steering wheel so she could make turns with one hand. After six months of practice, she passed a driving test in May 2022. At the end of July, she drove Adenike to daycare for the first time—and after missing so many ordinary but significant moments in her daughter’s life, she says, doing so felt “better than good.”

Less than a year later, the Stroke Comeback Center asked Erin to speak at a fundraising event at the State Theatre in Falls Church. She was reluctant but agreed to try. Working with a counselor to prepare a ten-minute speech about her medical journey, Erin spent three months practicing her delivery. On the night of the event, she wore a hot-pink pantsuit. Radiating confidence, she gave a talk that earned enthusiastic applause from the capacity crowd.

“I killed it,” she says with pride.

Survivors tend to make their most significant improvements three to six months following a stroke. After that, recovery often plateaus. Discouraged or even depressed, patients will lose interest in ongoing rehab, even though significant progress in regaining function remains possible. In one case detailed in a medical journal, a man recovered the use of a nonfunctional hand 23 years after a severe stroke.

Erin is still pushing. Last year, I watched her meet with an occupational therapist, who spent about half an hour using massage, manipulation, and an inflatable air splint to straighten out Erin’s clenched right fingers and thumb. When it was over, the pain she felt in her hand had subsided, temporarily. More recently, Erin has been training with a specialized electronic arm brace that reads nerve signals from the muscles in her arm and uses small motors to open and close her hand as she intends. Working with another therapist, Erin is relearning how to pick up and release small items. Progress is slow—but if it continues, she could one day use both of her hands and arms to carry grocery bags, or hold Adenike’s hand while walking down stairs.

Erin still struggles with aphasia. The condition doesn’t impair intelligence, just speech, which can be maddening. On one of her Instagram posts, Erin asks others to “please don’t try to finish my sentences. Be patient and wait for me to find the word.” There’s also the risk of another stroke: According to the American Stroke Association, nearly one in four survivors will suffer one.

Erin and her family don’t dwell on that. Life at home is too busy—and also much improved. Adenike is now five years old, a bouncy, lively kindergartner who can’t wait to show guests how well she can write her name and find her birthday on a calendar. Mayo started his own pest-control business, allowing him to make his own schedule. He’s getting more rest these days, as Erin has become more capable and the children are older and more able to help out. Mayo is grateful that God gave his wife a second chance, and deeply proud of all she’s accomplished in her recovery. He believes her stroke has strengthened their bond. So does Erin, who says her husband is “resilient and so much stronger than I ever imagined.”

The same can be said of Erin. Like Mayo, she draws strength and hope from her religious faith and sees her survival as a miracle. Healing, she says, is about more than recovery—it’s about finding new ways to thrive.

At church, Erin recently took a class about identifying one’s purpose in life, and she realized she already had one: lifting up other survivors and inspiring them to keep moving forward. Following her stroke, Erin’s smile became significantly lopsided, but these days, it’s almost back to the way it was: big and bright, probably because she uses it so often.

“Tell your wife goodbye,”

said the nurse. Mayowa Adelekun waved from behind a window as a gurney holding his wife, Erin, was hoisted into a medevac helicopter. Rotors roaring, the aircraft lifted off from the roof of Anne Arundel Medical Center in Annapolis and headed 30 miles west to MedStar Washington Hospital Center, where a trauma team was waiting.

Nine days earlier, Mayowa and Erin had been giddy with joy at the birth of their daughter, Adenike. A post-delivery photo taken in this same hospital shows her resting on Erin’s chest, swaddled in a blanket and wearing a pink cap. Mom beams from under a puffy hair cover. Daddy leans awkwardly into the shot, his facemask pulled down to show his proud grin.

Mother and daughter had gone home healthy—but now Erin had returned with a life-threatening stroke. As the helicopter receded into the distance, Mayowa didn’t know if he was saying goodbye for the moment or goodbye forever. Doctors didn’t know, either. Only one thing was certain: Mayowa wasn’t allowed to ride along, nor to enter the next hospital. It was August 2020, six months into the coronavirus pandemic. No vaccines were available yet. Covid had already killed thousands of Americans. Hospitals were overcrowded and had banned visitors to limit its spread.

Sobbing in fear and frustration, Mayowa headed home, where his mother-in-law was waiting with Adenike and his two older children. From his car, he called MedStar Washington. The person on the phone told Mayowa they hadn’t received the body yet. Those words—the body—gave him an icy chill.

Mayowa, whose family calls him Mayo, and Erin Calloway met on the Plenty of Fish app. Online dating wasn’t her thing, but a friend had found a partner there and persuaded Erin to try it, just for a week. Erin got lots of messages from men who hadn’t bothered to read her profile, and she was ready to quit when she saw one from Mayo. He shared her passion for Game of Thrones, and she liked his sense of humor enough to meet him at Dave & Buster’s—a noisy cross between a diner and a video-game arcade that offered plenty of distractions if the date didn’t go well.

“We just clicked,” Erin says. “We started hanging out every day, and on a car trip to Atlanta we decided to get married.”

They did, just six months after that first date. Mayo fell in love with Erin’s “good heart” and “listening ear.”

“We were destined to be together,” he says.

Three months before the couple met, Erin’s sister, Betsy, had died from kidney failure at age 36. The two were very close, and Erin had previously given Betsy one of her kidneys, a gift that kept her sister alive for an extra decade. “Betsy passing made me think life is short and you just need to take chances,” Erin says. Taking a chance on Mayo, she adds, “paid off because we’ve been happily married for eight-plus years.”

At first, both of their families—Erin’s in Maryland and Mayo’s in Nigeria—wondered if their union would last. The newlyweds threw themselves into family life in Bowie with Mayo’s two young children from a previous marriage. Erin worked for a financial company; Mayo sold cars and, when sales were slow, did rideshare and delivery gig work. He went back to school at a community college. The family moved to Richmond for a few years after Erin got a promotion, but they were happy to return to Maryland when the opportunity arose.

By that time, Erin was pregnant. The older kids were excited: Mayo’s son wanted a boy, and his little sister was pulling for a girl. At 38, Erin was considered old to be a first-time mother. Yet while health workers described her pregnancy as “geriatric,” she found it to be easy and uneventful. Covid was a source of stress, but she and Mayo were careful. Both tested negative right before Adenike’s delivery date. She was born by cesarean section at Anne Arundel Medical Center on July 24, 2020.

C-section recovery usually takes about six weeks, and most women spend two to four nights in the hospital. Because of Covid, Erin’s care team told her she’d be much safer at home and discharged her after two nights. When Erin mentioned she had a headache, a doctor recommended she take Tylenol, which eased the pain. But the Sunday after she went home, eight days later, her headache returned—stronger than before. Exhausted from her surgery, lack of sleep, and constant breastfeeding, Erin made a mental note: If she still felt bad on Monday, she’d call the doctor.

The next morning, August 3, Erin woke up with the worst headache of her life. The doctor’s office wasn’t open yet, so Mayo suggested she rest a little longer while he made her some tea and Nigerian custard. When he called out to say breakfast was ready, Erin tried to answer, but no words came out—all she could utter was “Arr, arr, arr.” She stood up shakily and groped her way down the stairs of their townhouse and into the kitchen, where Mayo was waiting. Suddenly, her right arm went limp. At that moment, they both realized she was having a stroke.

Mayo got Erin into the car and raced to the hospital. Terrified, he tried to act calm, reassuring his wife that everything was going to be okay. Sitting in the back seat, Erin was overwhelmed by mute panic: What would happen to Adenike if she didn’t survive? She desperately needed to tell Mayo that only two pouches of pumped breast milk were in the refrigerator. Baby formula would work, but did he know how to prepare it? She needed to tell him so many things.

Arriving at Anne Arundel Medical Center, Erin was rushed to the imaging department. She had a seizure on the MRI table. Hoping to prevent additional damage to her brain, doctors put her into an induced coma before having her airlifted to MedStar Washington Hospital Center.

A few hours later, MedStar neurosurgeon Jeffrey Mai called to tell Mayo that his wife needed an emergency procedure. “We’ll try our best,” Dr. Mai told Mayo, “but I cannot promise anything about the outcome.”

While strokes after giving birth are rare, they happen more than you might think. According to the American Heart Association and the American Stroke Association, 30 of 100,000 pregnant women will experience one. Compared with the incidence in non-pregnant women, stroke risk is three times greater during the third trimester and the first three months postpartum. The risk is higher still for African American women, those who deliver via cesarean section, and women who experience high blood pressure during pregnancy.

Strokes occur when blood flow to the brain is interrupted. They’re the fifth-leading cause of death in America. The vast majority are ischemic, which means a blood vessel is blocked. Erin’s stroke, however, was hemorrhagic: Burst vessels on both sides of her brain were pouring blood into her cranium, squeezing her brain into a shape it wasn’t meant to be.

Mai wanted to avoid cutting into Erin’s brain, so he installed a tube inside her skull to drain blood and relieve pressure. The medical team chilled her whole body, a strategy for reducing brain activity and limiting damage. But hours later, Erin’s blood pressure was still critically elevated. A high-risk surgery was her only hope. Mai removed a large piece of Erin’s skull in order to reduce the ongoing pressure on her brain, and he placed that “flap” of skull in her abdomen, the safest place to store cranial bone until it can be returned to its place of origin—assuming the patient survives.

Two days later, Mai called Mayo at 9 pm. He had arranged for Mayo to visit his wife, despite the pandemic lockdown. The doctor feared Erin might not make it through the night. Arriving at the intensive-care unit, Mayo was shocked to see his unconscious wife surrounded by machines and monitors. Her face was obscured by ventilation equipment. A drainage tube snaked out of her heavily bandaged head. A tangle of lines and cables connected her to IV drips and monitors.

Mayo reached for Erin’s hand. He said prayers. He sang to her for hours. There was no response. Mayo believed that Erin’s future was in God’s hands—he could only hope that prayers would make a difference. He did not say goodbye.

When Erin first regained consciousness, she thought she was dreaming. Despite dazzling bright light, she could barely make out foggy images of people in hazmat suits floating around her. She now had Covid and pneumonia—putting her health in even more danger—and didn’t understand anything the suited people were telling her.

On a video call that Erin’s caregivers set up, Mayo told his wife she’d had a stroke, that her survival was miraculous, and that she’d been unconscious for almost a month. Adenike, he reassured her, was fine. That helped to hear. Only Erin couldn’t speak. She was immobile, tethered to equipment. Her head was surrounded by cushioning to protect her skull. Her right side was paralyzed, and her only way to communicate was by using her left hand to point to pictures. It took several people to move her into a wheelchair, and she had to wear a protective helmet anytime she got out of bed.

Erin didn’t yet understand how fortunate she was. More than a third of people who suffer a cerebral hemorrhagic stroke like hers don’t survive the first month. Many others don’t make it through the first year. Researchers aren’t entirely sure why pregnant and postpartum women are more susceptible to bleeding in the brain—high blood pressure and the fact that the heart has to work harder before and after birth may increase risk—but their numbers have been increasing over the past few decades.

After 29 days in the ICU, Erin was moved next door to National Rehabilitation Hospital. The transition was joyful—I’m still alive!—but the road ahead was daunting. She’d have to relearn how to walk and talk while also working to get her paralyzed right arm, hand, leg, and foot functioning again. Her rehab team crowned her with a new helmet, bejeweled with multicolored glass gemstones. She was still in bed when her physical therapy began, and she wasn’t happy when the therapist raised her fully upright and batted a balloon at her. It took a week for Erin to move her arms enough to start batting it back. She was fitted with a brace on her unresponsive right foot and ankle and was hooked up to a pulley system to help her get up and down into a chair. A month and a half after her admission, she finally got out of the chair on her own and took five steps using a four-point cane.

Before the stroke, Erin was right-side dominant, but now her right hand was balled up in an unresponsive fist. She couldn’t lift her right arm, and her right leg wasn’t cooperating, either. While working to regain some function on that side, Erin also had to learn to do everything left-handed. At the same time, she had to relearn how to talk. She suffered from global aphasia, a severe language disorder caused by brain injury.

Erin’s first goal was to learn to say the names of family and friends. A group of friends made a banner with photos and names, which a speech therapist hung in her room. Erin studied it every day. With Covid protocols, Erin was allowed to have a single adult visitor each week, usually Mayo, arriving with cellphone photos of Adenike. In September, he arranged a group video call with the people in the pictures for Erin’s birthday, and she managed to greet everyone by name—including Adenike, whose name was the hardest for her to say.

“Words can’t describe what it meant to me to have that call,” Erin says. “Everyone must have thought I was a zombie because I made no expressions. It may have looked like I was out of it, but inside I was thanking God for my family and friends.”

Erin was discharged after three months. When she got home, Adenike was crying. Still wearing a helmet to protect the soft side of her head, Erin settled on the sofa, holding her baby to her chest.

“She remembered I was her mother,” Erin says. The crying stopped.

For most stroke patients, going from hospital to home is the biggest challenge. “Reality sets in,” says Dr. Emma Nally, who specializes in brain injury and stroke recovery at National Rehabilitation Hospital. In addition to dealing with ongoing physical symptoms, patients and their families have to schedule medical appointments, deal with health insurance, and handle tasks as simple as getting to rehab—which isn’t so simple when a patient can’t walk or drive themselves. For postpartum patients such as Erin, the care and feeding of an infant can add more stress.

For a brief time after Erin came home, her family had a home health aide—but mostly it fell to Mayo to care for everyone: two school-age children with their activities and homework, three-month-old Adenike, and Erin, who needed almost as much attention as their infant daughter. Each morning, he’d get the baby fed and dressed and the older children ready for school. Then he’d help Erin bathe, dress, and go downstairs, where she’d stay, working several days a week with therapists who came to the house, until Mayo returned from work. Erin’s mother would help out, but she was in her seventies and couldn’t do any heavy lifting. Meanwhile, Erin was unable to pick Adenike up or change her diapers—not with only one functional hand—so Mayo had to take the baby to daycare.

Overnight, Mayo would change Adenike’s diapers and help Erin get to the bathroom and back. He never got a good night’s sleep and was perpetually exhausted. When the pest-control company where Mayo worked couldn’t give him a flexible schedule, he had to quit. The family relied on disability coverage from Erin’s employer.

Nally says Erin is lucky: She has a strong family support network and access to excellent care in the Washington region. (Stroke patients in rural areas, by contrast, have far fewer options nearby.) Erin and Mayo tried to stay positive despite all the stress—but each could see the frustration and worry in the other’s face. Mayo tried to take everything one day at a time, believing God was in control and relying on a family friend who is a neurologist to explain what Erin was going through. Still, he struggled with all of his new responsibilities and had no clear vision of what the future held. Erin had been the family’s caregiver, the “fun one” who’d organized everything for everyone. Now she was relying on others, and felt awful about it.

Early in her recovery, Erin thought she might wake up one day and be back to normal. She saw a doctor who evaluated her for Social Security disability benefits. He told her she’d never work again. But I’m just 39 years old, she said. She has a business degree from Morgan State University and a master’s in communications from Georgetown and had a successful career before the stroke.

The doctor shook his head—nope, not going to happen.

“That doctor lit a fire in me,” Erin says.

Determined to reclaim her independence, she set a goal: to reach the best version of “normal” she could achieve. She progressed from using a walker to taking short, unassisted walks outside the couple’s Upper Marlboro home, with Mayo watching nervously from inside. Nine months after her stroke, she had surgery to repair her skull. Soon after, her headaches subsided, and Erin—who loves to laugh—was able to do so without pain. Her helmet was history.

Regaining speech was harder. A vivacious extrovert, Erin was “embarrassed to talk.” When she tried, listeners often turned to Mayo to ask what she’d said. That hurt. Erin found an app that allowed her to practice speaking privately. She connected with the Stroke Comeback Center in Vienna, a nonprofit that offers affordable programs for stroke survivors and their families. The center has professional counselors on staff, but much of the support it provides comes from survivors helping one another. At first, Erin was silent in group conversations there—but over time she began joining in, and even worked on the center’s podcast.

Gaining confidence, she posted about her recovery on Instagram with the handle @Stroke.Mama. Erin found this therapeutic, a way to encourage herself and others. Mayo took the photos and videos for her posts, which are full of self-deprecating humor. She attracted hundreds of followers, who chimed in with comments like “You are an inspiration to me” and “You are unstoppable, girl.” Eventually, the American Heart Association of Greater Washington recognized Erin’s social-media feed, giving her a “Leader of Impact” award for her willingness to show her struggles and encourage other survivors to advocate for themselves.

Erin had her car modified to accommodate the stiffness on her right side: The gas pedal was moved to the left, and a knob was added to the steering wheel so she could make turns with one hand. After six months of practice, she passed a driving test in May 2022. At the end of July, she drove Adenike to daycare for the first time—and after missing so many ordinary but significant moments in her daughter’s life, she says, doing so felt “better than good.”

Less than a year later, the Stroke Comeback Center asked Erin to speak at a fundraising event at the State Theatre in Falls Church. She was reluctant but agreed to try. Working with a counselor to prepare a ten-minute speech about her medical journey, Erin spent three months practicing her delivery. On the night of the event, she wore a hot-pink pantsuit. Radiating confidence, she gave a talk that earned enthusiastic applause from the capacity crowd.

“I killed it,” she says with pride.

Survivors tend to make their most significant improvements three to six months following a stroke. After that, recovery often plateaus. Discouraged or even depressed, patients will lose interest in ongoing rehab, even though significant progress in regaining function remains possible. In one case detailed in a medical journal, a man recovered the use of a nonfunctional hand 23 years after a severe stroke.

Erin is still pushing. Last year, I watched her meet with an occupational therapist, who spent about half an hour using massage, manipulation, and an inflatable air splint to straighten out Erin’s clenched right fingers and thumb. When it was over, the pain she felt in her hand had subsided, temporarily. More recently, Erin has been training with a specialized electronic arm brace that reads nerve signals from the muscles in her arm and uses small motors to open and close her hand as she intends. Working with another therapist, Erin is relearning how to pick up and release small items. Progress is slow—but if it continues, she could one day use both of her hands and arms to carry grocery bags, or hold Adenike’s hand while walking down stairs.

Erin still struggles with aphasia. The condition doesn’t impair intelligence, just speech, which can be maddening. On one of her Instagram posts, Erin asks others to “please don’t try to finish my sentences. Be patient and wait for me to find the word.” There’s also the risk of another stroke: According to the American Stroke Association, nearly one in four survivors will suffer one.

Erin and her family don’t dwell on that. Life at home is too busy—and also much improved. Adenike is now five years old, a bouncy, lively kindergartner who can’t wait to show guests how well she can write her name and find her birthday on a calendar. Mayo started his own pest-control business, allowing him to make his own schedule. He’s getting more rest these days, as Erin has become more capable and the children are older and more able to help out. Mayo is grateful that God gave his wife a second chance, and deeply proud of all she’s accomplished in her recovery. He believes her stroke has strengthened their bond. So does Erin, who says her husband is “resilient and so much stronger than I ever imagined.”

The same can be said of Erin. Like Mayo, she draws strength and hope from her religious faith and sees her survival as a miracle. Healing, she says, is about more than recovery—it’s about finding new ways to thrive.

At church, Erin recently took a class about identifying one’s purpose in life, and she realized she already had one: lifting up other survivors and inspiring them to keep moving forward. Following her stroke, Erin’s smile became significantly lopsided, but these days, it’s almost back to the way it was: big and bright, probably because she uses it so often.

This article appears in the November 2025 issue of Washingtonian.