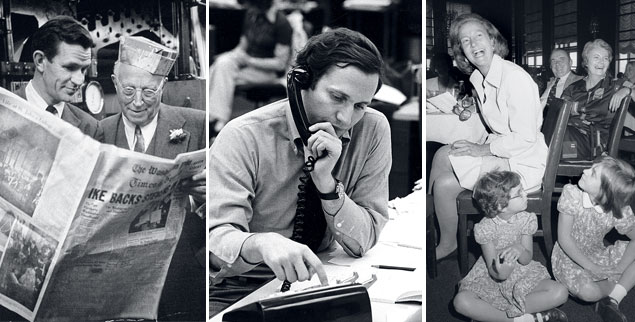

Former Washington Post executive editor Leonard Downie

Jr. was driving on Monday, August 5, when he got a call from the paper’s

owner, Donald Graham. In several hours, Graham would tell the staff he was

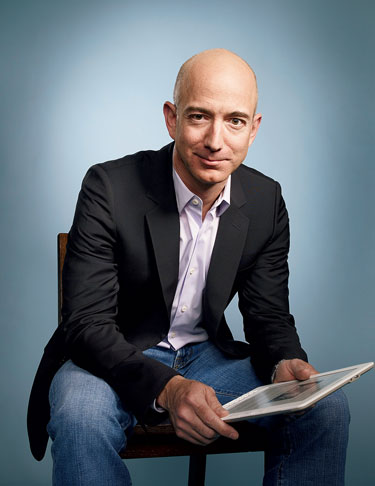

selling the Post—his family’s crown jewel for 80 years—to Amazon

founder Jeff Bezos for $250 million.

Graham didn’t have answers to the questions the newspaper

industry posed. Neither he nor his niece, publisher Katharine Weymouth—the

fifth family member to run the paper since her great-grandfather Eugene

Meyer bought it in a bankruptcy sale—could see a way to combat

internet-driven pressures without more budget and staff cuts. The phone

call was Don Graham’s admission of defeat. “I didn’t know anything about

this,” says Downie, who has worked with Graham for 42 years. “I was

speechless. I had to pull over.”

Downie drove home, changed clothes, and went into the office.

He stopped by Graham’s office to thank him. “We know each other so well

that we can sense each other’s feelings,” Downie says. “He didn’t have to

tell me it was a tense, difficult decision.”

Downie’s replacement as executive editor, Marcus Brauchli—who

stepped down last year to become a vice president of the Post’s

parent company—walked into Graham’s weekly Monday 3 pm staff meeting. The

owner shut the door, then said to the group: “I have shocking

news.”

• • •

The entire staff needed to be told. Management sent out an

e-mail at 4:15 announcing a 4:30 meeting that day. But Post media

reporter Paul Farhi worried that even that was too much time.

Farhi had been on vacation in the Dominican Republic when

executive editor Marty Baron called. Baron needed him back home to write a

story, but he wouldn’t give Farhi any details other than telling him he’d

call him on Sunday, August 4. They spoke for 45 minutes that day, and

Farhi was told about the sale but sworn to silence. After crafting his

story in a Word document at home, he arrived at work around 3 on August 5

in a daze, knowing a secret that would turn the Post inside out

but unable to tell anyone.

Farhi’s biggest fear—and that of the few people at the paper

who knew—was that another media organization would break the news. The day

before, the New York Times had profiled Weymouth without any hint

of what was to come. Times reporter Sheryl Gay Stolberg had asked

Graham if his niece would inherit his job running the Post Company. “[H]e

ducks the question,” Stolberg wrote, quoting him as saying, “I’m not

expecting her to go anyplace.”

That’s correct—for now. Under the sale terms, Weymouth and her

management team, Baron and editorial-page editor Fred Hiatt, will stay on

for at least a year.

At 4:30 pm, most of the paper’s 2,000 employees appeared in the

auditorium. Many believed they were going to learn that the Post

building had been sold—a widely reported possibility.

It had not.

Bezos had bought the Post, its printing presses, the

Express newspaper, the Gazette Newspapers, Southern Maryland

Newspapers, the Fairfax County Times, El Tiempo Latino, and

Greater Washington Publishing—basically everything needed to produce the

Washington Post and its website.

• • •

Graham—the 68-year-old son of legendary Post publisher

Katharine Graham—read a brief speech.

“I was surprised he’d written down what he wanted to say,” says

Downie, who joined the Post in 1964. “He’s a good extemporaneous

speaker. He may have done it for legal reasons, but I think it was more so

he could get through it.”

Some in the auditorium cried at the announcement.

Graham soldiered on, his voice quivering: “To say the very

obvious, I’ve loved working with you. Not just those who write the

stories, but those who run the presses, sell the ads, deliver the papers.

. . . I understand there is also, and necessarily, a sense of

disappointment on my side. The only person I feel even a slight sense of

disappointment with would be me. But not you. No one had a better bunch of

people to work with.”

The next day he reiterated that sentiment, telling

Post media blogger Erik Wemple, “I disappointed

myself.”

• • •

For Don Graham, selling the Post is like putting a

baby up for adoption. The biological parent knows the child will have a

better life than he or she can provide. But giving up that baby is still

painful. It’s an admission that you can’t provide what the child

needs.

Brauchli says putting the Post before his own feelings

is what Graham is about: “He takes the greatest pride in doing the right

thing, however difficult. He is immensely dedicated to his people and the

history and legacy of the institution. He felt he was doing what was right

for the institution. The pain was secondary.”

Robert Kaiser, who has worked with Graham since 1971, recalls a

line that Graham’s grandfather Eugene Meyer said in 1954 after he bought a

competitor, the Washington Times-Herald, for $8.5

million. Don Graham was eight; his grandfather was 78. Purchasing the

Times-Herald while owning the Post meant Meyer had

secured the future for the next generation.

“The real significance of this event,” Meyer said, “is that it

makes the paper safe for Donnie.”

It did for decades—until a perfect storm fueled by the web,

technology, and a recession brought the paper to its knees.

“On some level, Don must feel now that he has let the family

down,” says Kaiser, an associate editor who joined the paper in 1964. “He

didn’t live up to their expectations to keep the Post going. It

was an extremely difficult decision and at the same time

courageous.

“I think Don faced up to the fact that the only strategy

Katharine [Weymouth] and he had wasn’t really a strategy. They were

waiting for something to produce more revenue, and it never happened. He

understood it was a long, downward glide involving more cuts.”

• • •

This month, Post ownership will legally be handed over to Jeff

Bezos. A bash for current and former Posties is planned at the paper to

celebrate Graham and his family.

Graham—who will still be chairman of the board of the

not-yet-renamed Post Company—is a deeply private man. A week after the

sale, he told Washingtonian he was “interviewed out.” But he

wasn’t likely to be that forthcoming anyway. That’s not who he

is.

Post veteran Dave Kindred’s 2010 book, Morning

Miracle: Inside the Washington Post, noted that Graham is a dream

owner but also “every inquiring reporter’s idea of a frustrating interview

(so much there, so little said) . . . .”

Peter Perl, who worked at the Post for 32 years, was

assigned to write an advance obituary about Graham as he nears his eighth

decade—standard news procedure for prominent figures. Perl interviewed

dozens of people in Graham’s life.“Nobody knows Don on a deeply personal

level,” Perl says, “even people who are friends. He just got married [to

his second wife] and recently had a grandchild—I can see him saying, ‘I

want to leave this thing in good shape and want the newspaper to always be

there.’ ”

Graham has an elder sister, Lally Weymouth, and two younger

brothers, Bill and Steve. None works day to day for the Post Company,

though Weymouth writes occasionally. Graham’s daughter Laura O’Shaughnessy

is general manager of SocialCode, a Post Company start-up that helps

businesses develop their brand on Facebook. Her husband, Tim, is CEO of

LivingSocial. Graham’s daughter Molly went to work for Facebook in

2008.

I reached two of his close friends, Boisfeuillet “Bo” Jones

Jr., who worked at the Post for 32 years, and Nick Friendly. They

had gone to St. Albans School with Graham and have remained close. Both

offered to talk about what the sale meant to him, but only with Graham’s

approval. He didn’t give it.

Lally Weymouth and her daughter Katharine also declined to be

interviewed, as did Graham’s daughter Laura.

• • •

Kindred’s book says Graham once told a staffer that he started

each day by looking in a bathroom mirror and saying, “Don’t screw it

up.”

Some may say Graham screwed it up. Forbes ran a

February 2012 article titled nice guy, finishing last: HOW DON GRAHAM

FUMBLED THE WASHINGTON POST CO. A Vanity Fair story last year was

equally harsh, while describing how much everyone at the Post

loved him.

The reality is the Post has tried many things in the

last two decades. Some worked, but none was the holy grail. The internet

robbed the Post of lucrative print advertising as readers moved

online and circulation dwindled from a high of 830,000 in 1994 to today’s

474,767. Craigslist ate away at the once reliable cash cow, classified

ads. During the last seven years, the Post Company’s newspaper division

has seen a 39-percent drop in operating revenues. The future isn’t looking

any better.

Twenty-one years ago, Bob Kaiser attended an Apple-organized

conference in Japan on the “future of multimedia.” No one at that

gathering predicted the demise of newspapers. But on August 6, 1992,

Kaiser sent a memo to Post higher-ups.

“All saw an important place for us,” Kaiser wrote about the

conference attendees. “. . . But if newspapers are not about to become

extinct, I came away convinced that inevitably, more and more people will

want to use their computers to consume our products. As the number of such

people grows, so do our business opportunities.”

One suggestion he pushed was electronic classifieds: “Would

someone looking for a reliable car for a kid going to college prefer our

current [print] listings, or a list of all small cars with less than

60,000 miles selling for $5-7,000?”

He got nowhere. “The business side showed no interest in what I

said about classified ads,” he says. “They didn’t want to cannibalize our

own product. Tragic mistake. We might have been Monster.com.”

Kaiser had some success. He recommended creating an electronic

version of the paper, which the Post did; that eventually evolved

into Washingtonpost.com.

Steve Coll, who worked at the paper for 20 years, including as

managing editor from 1998 to 2004, insisted the Post should

capitalize on its national brand—about 80 percent of online readers came

from outside the Washington area, a figure that’s risen to 90

percent—rather than focus all its energies on the local franchise. Graham

disagreed. Coll left the Post, later telling Vanity Fair

he didn’t want to be “managing decline.”

“Don worked that problem with greater patience and creativity

than most publishers,” Coll says today. “He invested in web and digital

strategies. He brought in experts from Silicon Valley. He brought [media

executive] Barry Diller onto the board. He put technologists on the

problem. He tried to think outside the lines about advertising

models.”

The truth is that no newspaper has figured out how to monetize

the internet.

“I appreciate why he called time on his own effort,” Coll says.

“He felt he had done as much as he could.”

• • •

It’s easy to second-guess. If only Graham had been more

hard-nosed in 2005. That’s when Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, after

receiving a higher offer, asked to get out of a handshake deal with Graham

for the Post Company to invest $6 million in Facebook. Graham released

him. If he hadn’t, the Post’s stake might be worth $7 billion,

according to PrivCo, a firm that researches private companies. The

agreement would have given the Post Company the deep pockets it

needed.

If only Graham had bought more Berkshire Hathaway stock when he

met Warren Buffett in 1974. The stock was selling for $50 a share; at

press time it’s $170,500. “That was a much bigger miss than Facebook,”

Graham said in an interview on WAMU.

But the real problem the Post had—and why it had to be

sold—was that its owners failed to find a business model that would

satisfy their shareholders.

In 1971, the Graham family took the company public. The stock

opened at $26 a share. The paper did well financially until the digital

revolution. Owning Kaplan, the highly profitable education company, helped

the Post through the tough times until Kaplan started to lose

money in 2010 when government regulators cracked down on the for-profit

education industry.

Graham and other executives and editors experimented. But

quarter after quarter, the board and shareholders wanted to see their

stock rise, not lose value. They were looking at the seventh year of

declining revenues.

“How many public failures you can have is affected by

shareholder reaction,” says Jim Brady, executive editor at the

Post’s website from 2004 to 2009 and now editor-in-chief of the

privately held Digital First Media. “At a private company, you can

reorganize, restructure, try some things. If it doesn’t work, you live for

another day.” A private company, depending on the owners, can afford to

make mistakes without shareholder pressure.

The Post, according to media analyst Ken Doctor, ran

out of three key commodities: time, money, and ideas. “They didn’t have to

sell immediately,” Doctor says, “but depending on family and board

pressures, they knew there would be more cutting coming, given the

downturn in print advertising.”

Doctor says the 11-member Post Company board helped force the

reckoning.

“I knew there were some rumblings, especially through the board

of directors,” says longtime Post reporter and editor Bob

Woodward of the sale. “Directors have to represent the stockholders. They

are looking at this asset dwindling in value. If you look at it strictly

as a business issue, you’ve got to do it.”

• • •

According to a Post insider, the idea of selling began about

two years ago when Katharine Weymouth went to her uncle, who replied,

“Absolutely not.”

“Katharine flew to Omaha sometime last year to see Warren

Buffett,” this person says. “The thing she and Don agreed on was they

needed to find out what Buffett had to say. You have to understand the

extent that he is a guru to Don.”

Buffett owns 28 percent of Post Company stock. He was a friend

and mentor to Katharine Graham and is a father figure to Don, who at age

18 lost his dad, Philip Graham, to suicide.

“Katharine [Weymouth] lays out the situation financially and

asks Buffett for his advice,” the insider explains. “Buffett said to her,

‘If you were my daughter, I would tell you to get out.’ ”

Weymouth presented the idea at a lunch with Graham at DC’s

Bombay Club in late 2012, according to a Post account. “That

meeting triggered months of remarkably quiet maneuvering for a company

that ordinarily prides itself in dragging other people’s secrets into the

light,” wrote Craig Timberg and Jia Lynn Yang in an August 6 Post

article.

“The Post is [Don Graham’s] baby,” Weymouth said in

the story. “He was not going to give his baby to anybody who he thought

would not care for it properly.”

Leslie Hill understands such a decision. Hill is a member of

the Bancroft family that held more than half of the voting stock for Dow

Jones, which owned the Wall Street Journal. “For me it was very

emotional,” Hill says of the Journal’s 2007 sale to Rupert

Murdoch. “Your family has had this asset for 105 years, and it’s being

sold on your watch.”

Hill says she knew for a number of years that the

Journal had to be sold because it wasn’t going in a direction

that could be sustainable, let alone profitable: “That said, it’s very

difficult to say the time to sell is right now.” It was especially hard

because Hill didn’t want to sell to Murdoch.

Sarah Ellison covered the Journal’s sale as a reporter

for the same paper, and she wrote a book about it. Last year, Ellison

profiled the Post for Vanity Fair. “With every sale of a

family paper, there comes a moment when the family believes the paper will

be better off under someone else’s ownership,” Ellison says. “That’s what

they believe to get themselves over this hump. That’s what the Bancrofts

did. I imagine that’s what Don was thinking. It’s a pretty startling thing

to come to grips with if you are born into the paper with all the

expectations that Don had.”

Allen & Co., an investment firm, was hired to help find a

buyer. Graham said on PostTV, the paper’s video arm, that there were fewer

than a dozen prospective buyers. Allen & Co. contacted Jeff Bezos in

March or April, but the discussion didn’t seem to go anywhere. Then in

July, Graham attended Allen & Co.’s media conference in Sun Valley,

Idaho, and met with Bezos twice. Eventually, they reached a

deal.

It’s poignant that the moguls came to an initial agreement in

Sun Valley, where Graham’s mother, Katharine, died in 2001 after falling

while attending the same conference.

• • •

Don Graham, many say, likely spoke to few about selling his

baby.

“When I asked him to talk about past decisions in his life, he

very often literally would talk to no one before doing something,” Peter

Perl says. “He didn’t tell anybody until he made the decision [in 1967] to

go to Vietnam and had already signed up. He didn’t tell his wife. It’s not

a chatty family.”

On August 5, Post Company directors approved the sale in a

conference call. Director Dave Goldberg, CEO of SurveyMonkey, said in an

e-mail that the directors weren’t allowed to talk about the details.

Because the company is publicly held, under SEC rules it had to make the

sale public immediately. So Graham and Weymouth hastily convened their

employees.

It has all the tragedy of a 19th-century novel, says New

Yorker editor and former Postie David Remnick. Graham tried to do

everything right, and for years he succeeded. “And then along comes a

technological revolution that throws it all into chaos,” Remnick says by

e-mail. “And then, because he sees no good future for his company or for

the paper, he sells it—to a leader of that revolution.”

Adds Steve Coll: “Selling the paper doesn’t diminish the

achievements of his lifetime, but it’s not the way Don wanted it to

end.”

Alicia Shepard (aliciacshepard@gmail.com) is a media writer

and the author of Woodward & Bernstein: Life in the Shadow of

Watergate.

This article appears in the October 2013 issue of The Washingtonian.