George Cassiday’s bootlegging career began relatively

innocently—a clandestine whiskey drop for two Southern congressmen—but

soon his impeccably tailored suit and green felt hat became well known on

Capitol Hill.

In 1920, fresh off a tour of duty in World War I, the West

Virginia native walked off a French freighter and into one of the worst

job markets in US history. With Prohibition in full swing, a well-paid

friend explained that bootlegged booze was bringing a pretty penny.

Especially with DC politicos.

Cassiday would wheel his heavy luggage, overfilled with liquor,

into the House Office Building, tip his trademark topper to the door

guards, and make his rounds of discreet bureau drawers and library

shelves—responding to 25 calls a day, on average, from thirsty

lawmakers.

After five years, Cassiday’s cover was blown. As agents carted

him away, the sergeant-at-arms on the scene told reporters that “a man in

a green hat” had been busted for bootlegging. Cassiday was banned from the

House, never to supply again, they reported.

Instead, Cassiday took his green hat and white whiskey across

the Capitol lawn, where he liquored up the Senate for another five years.

When his New York City suppliers’ stashes dried up, he cooked up his own

hooch and sold it out of the Senate Office Building’s stationery room. His

recipe was crude: a gallon each of rye, grain alcohol, and hot water, plus

a few drops of coloring.

By the end of his hooch-slinging career in 1930, Cassiday

estimated that he was keeping 80 percent of the House and Senate in drink.

“If they got a kick out of it with no bad side effects, they were well

satisfied,” he wrote in a 1930 Washington Post

article.

Handcrafted liquor has a much different connotation these days.

Small-batch spirit makers—those producing fewer than 100,000 cases a

year—are setting up shop around the country, much like the craft-brewery

renaissance that sprang out of the Pacific Northwest in the

1990s.

While craft liquors have taken off in the region, this fall an

industrious duo—retired lawyer Michael Lowe and son-in-law John

Uselton—began to do what no one has done in the nation’s capital in more

than a century: distill spirits within District lines.

Lowe and Uselton’s baby, New Columbia Distillers—the city’s

first microdistillery—opened in October in a developing neighborhood off

New York Avenue, Northeast. If all goes as planned, they’ll soon be

brewing 2,000 cases a year of the sort of small-batch gin and rye whiskey

that was stocked behind the bars of pre-18th Amendment DC. “We want to be

able to say we’ve made a little bit of history,” says Uselton.

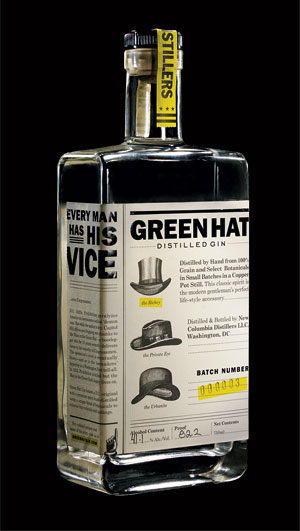

In a nod to DC’s past, their inaugural spirit is branded Green

Hat Gin.

Craft distilling is a tough market, especially going up against

industry giants such as Jack Daniel’s and Tanqueray, which sell 10 million

and 2 million cases a year, respectively. The good news for Lowe and

Uselton: DC likes to drink.

“People don’t realize that DC has always been considered the

biggest drinking city in the country,” says Derek Brown, owner of two DC

specialty-cocktail dens, the Passenger and the Columbia Room. “Sure, in

the past few years, we’ve seen a renaissance of sorts, with all these

craft bars coming in, with the breweries, but it’s always been a part of

the fabric of this city.”

Before Prohibition turned DC dry for 17 years, the highest

concentration of bars the country likely has ever seen, called Rum Row,

stretched along what’s now Pennsylvania Avenue. Almost eight decades after

Repeal Day, a typical DC drinker downs three gallons of distilled spirits

a year, second only to residents of New Hampshire, according to the Beer

Institute.

Lowe and Uselton want to capitalize on the thirsty local

market, but they have a steep learning curve. Both started out as beer

guys. Uselton was the beer buyer for Schneider’s of Capitol Hill; Lowe

dabbled in home brewing after retiring from a 30-year legal career. “We

chatted about doing a brewery, but I knew that a few were in the works in

DC,” says Uselton. On a whim, Lowe took a weekend distilling class at

Cornell University.

“I looked at a bottle of whiskey and thought, ‘I can never do

that,’ ” says Uselton. “I thought it must be a ten-year process and more

than I could handle.”

But when Lowe came back from Cornell, he had good news. “Seeing

the process in action made me realize that this isn’t magic—not at all,”

says Lowe, whose strawberry-blond mustache and round, wire-rimmed

spectacles make him look like a booze maker out of central casting. “It’s

art, certainly. But it’s doable.”

An apprenticeship out west at Spokane’s Dry Fly Distilling with

Don Poffenroth, a marketing executive turned craft distiller, cemented the

men’s interest.

Many hopeful spirit makers see distilling as the latest

get-rich-quick scheme, says Poffenroth, who believes it’s anything but. It

can take years to get into the black, and most distillery start-ups come

with a seven-figure price tag.

Scott Harris, co-owner of Loudoun County’s Catoctin Creek

distillery, has doubled production every year since opening in 2009 and is

set to produce 40,000 cases annually of white and rye whiskeys, gin, and

brandy. But he admits it was tough getting started. “The trick is getting

your product out there, branding it, selling it,” says Harris, who worked

in telecommunications before opening the distillery. “It’s going to become

more difficult as the market becomes more saturated with craft

distillers.”

To those passing the future home of New Columbia Distillery—a

90-year-old warehouse tucked between Gab Auto Repair and a

seafood-distribution center—early this year, the building was just an

empty cave of a space with nothing but a banged-up metal dumpster, some

makeshift lanterns, and the chalky waft of crumbling concrete.

Soon, though, the warehouse would be lined with whiskey-filled

oak barrels, Lowe explained. The smell of dust would give way to the

bitter aroma of vaporizing botanicals—juniper, coriander, angelica, and

orrisroot, to name a few—dangling from a copper hook over 450 liters of

boiling spirits.

“The fermenters will be lined up against this wall here,” said

Uselton, his deep voice echoing through the warehouse as he led an

impromptu tour, “and the mash tun—that’s the big tank that essentially

stews the grain—will be right about here.”

“It’s going to be a tight squeeze,” said Lowe, pacing the

length of the alembic—as the distilling vessel is called—still being built

some 4,000 miles away in a hamlet in southern Germany.

Months later, the still finally arrives at 1832 Fenwick Street

one July morning.

Lowe, Uselton, and Lowe’s son, Zack, are working at dawn to

unload the still and its appendages from a 40-foot-long shipping

container. As reggae from Zack’s iPod bounces around the warehouse, father

and son maneuver a forklift through a maze of bubble-wrapped stainless

steel and lopsided cardboard boxes, their contents scrawled in German. “Go

a little bit that way. Not that sharp. A bit backwards—there,” says Zack,

one hand wrapped around his coffee, the other giving his dad a

thumbs-up.

The 3,500-square-foot warehouse has the air of Christmas

morning, one box after another having been opened in expectant haste and

then cast aside, over and over until the biggest of all was reached: the

curvy, copper-crowned still, a year’s worth of planning and waiting

finally fulfilled.

As Zack watches the 15-foot-tall still nestle into its

position, his eyes go wide. “That’s gonna be a lot of liquor,” he

says.

The numbers are stunning: three tons of grain a month, 2,160

liters of mash per batch, four runs through the still, 6,000 empty

bottles. And $1 million on the line.

Lowe and Uselton know they’ve got a long road ahead. They have

to fine-tune the recipe, learn the ins and outs of the copper behemoth

residing in their warehouse, and, most important, secure a distributor

that can get their product onto the shelves of local liquor stores and

into bars like Derek Brown’s.

A month later, in the dining room of Lowe’s Chevy Chase home,

he and Uselton are putting the finishing touches on their gin recipe. The

walnut dining table is strewn with Mason jars bearing masking-tape labels

that denote their contents: Cassia. Coriander. Myrtle flower. Fennel

seed.

“We know the direction we want to go, but from there it’s a

matter of sniffing,” says Lowe as he lifts a tincture-filled jar to his

nose. “There’s some logic behind it, but there’s also an element of ‘let’s

try a little of this.’ ”

“It’s like a science project,” says Uselton, armed with a

rubber-tipped dropper and a fistful of measuring spoons.

“An art project,” Lowe corrects him.

As they mix infusions into a base of neutral spirit, the

conversation turns to the legacy they’re trying to honor in the release of

their first product.

“As we started looking into all of this history, Cassiday’s

story leapt off the page at us,” says Lowe, who first read about the Man

in the Green Hat in Garrett Peck’s book Prohibition in Washington,

DC. In it, Lowe discovered that Cassiday’s youngest son, Fred, still

lived in the area. Lowe and Uselton met Fred at ChurchKey, a 14th Street

beer hall, where they told him their idea: to become the first distillery

in DC since Prohibition and to name their booze after his

father.

“I was thrilled to death,” says Fred, 64, a retired Air Force

senior master sergeant. “I think Dad would be thrilled, too. He used to

take a lot of pride in telling us kids about what a big shot he was, and

of course nobody paid any attention to him—except when he got to a juicy

part.”

But, Fred says, George Cassiday never drank his own stuff. He

actually preferred beer. Cassiday, according to his son, was a Yuengling

man.

Though Fred himself is no gin drinker, he’s more than pleased

with the product, which started pouring from Uselton and Lowe’s still in

early October: “It’s the best I’ve ever tasted, I have to

say.”

Fred and his family were summoned to the distillery for the

bottling of one of the first full runs. Clad in green hats, Uselton and

Lowe presented Fred with case one, batch one, of Green Hat Gin—the

fulfillment of a promise made to him during their initial conversations.

“My dad would have loved it all,” says Fred. “I know he’s

proud.”

For now, Uselton and Lowe are spending 12-hour days at 1832

Fenwick Street, mashing, distilling, and bottling a 12-botanical

concoction with notes of celery seed and grapefruit peel, currently

offered at more than 25 establishments around the District. Clients

include Komi, Cashion’s Eat Place, Obelisk, Boundary Road, Ace Beverage,

and Derek Brown’s bars. The gin, which sells for $36, can also be picked

up at the distillery.

“We’re already bottling a batch a week,” says Uselton, who

notes that they will soon be developing their rye-whiskey recipe. “We’re

working six days—six very long days—a week, but everything’s coming

together.”

Former assistant editor Kathleen Bridges can be reached at kathleen.bridges@gmail.com.

This article appears in the December 2012 issue of The Washingtonian.