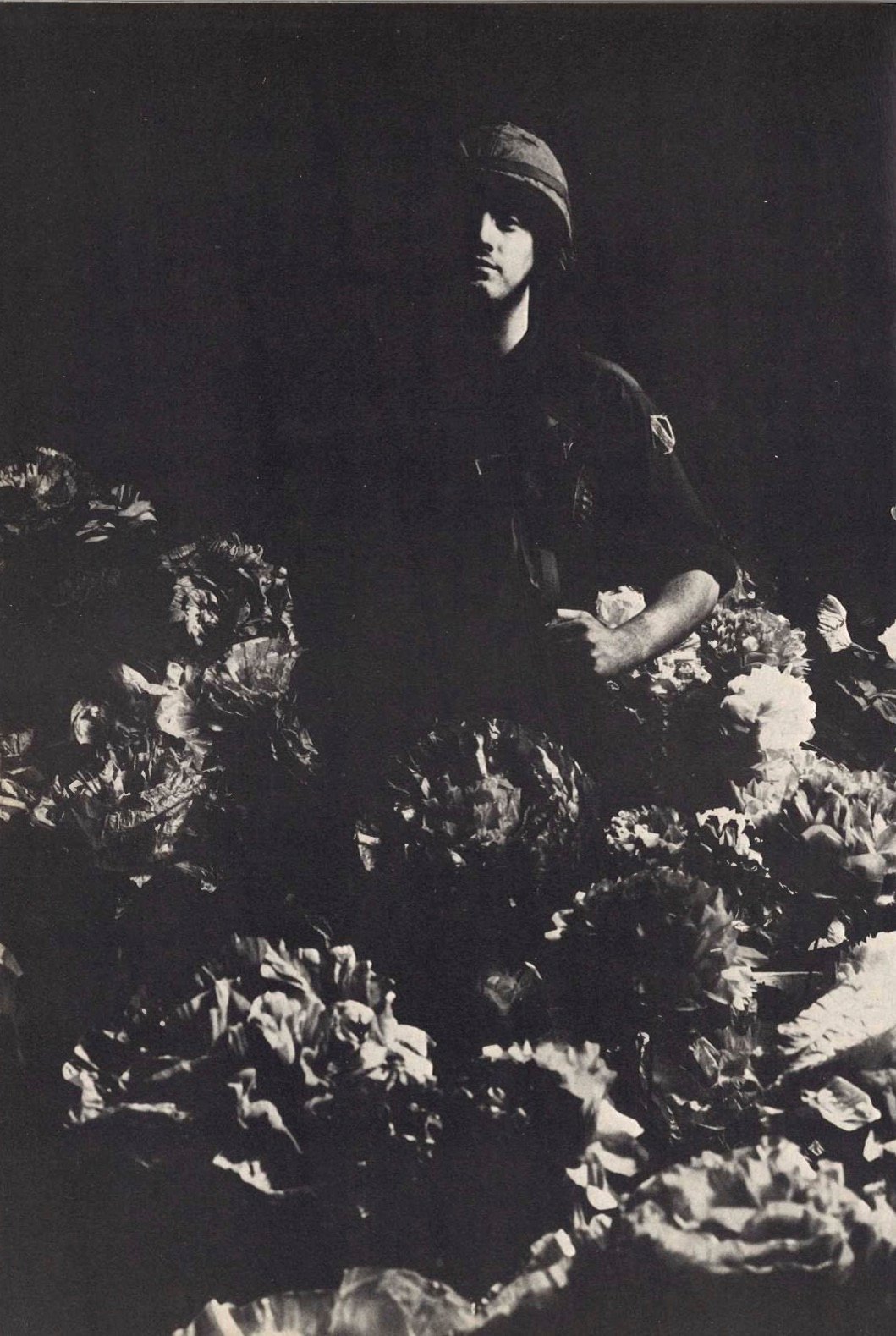

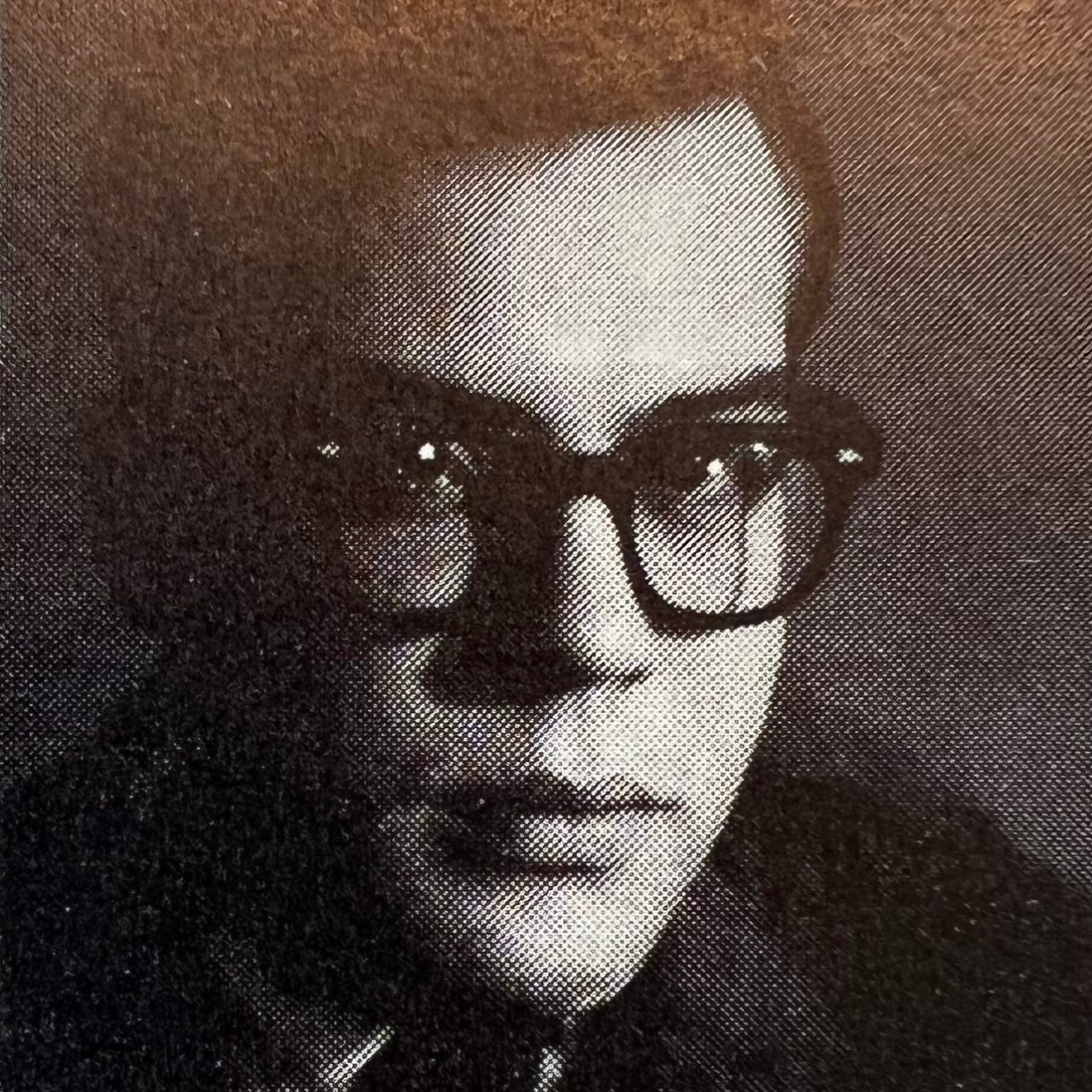

John Steinbeck IV was 21 years old when this article ran in the January 1968 issue of The Washingtonian. The son of the author of The Grapes of Wrath had returned from Vietnam the previous June, a blurb on the magazine’s contributors page said, “with a strong desire to go back.” He’d gathered string over twelve months as a reporter for the Armed Forces Radio and TV network and was working as a writer in the Army’s Chief of Information office when it was published. In March of that year, he testified about soldiers’ pot use before Congress, estimating that “about 60 percent of American soldiers between the ages of 19 and 27 smoke marijuana when they think it reasonable to do just that.” The military called press coverage of his remarks “irresponsible,” but, as a 1995 Army history reads, by 1969, “Evidence continued to mount nevertheless that marijuana smoking had reached major proportions in the war zone.” Steinbeck died in 1991.

Please note: This article includes some outdated language. Washingtonian is reproducing the text here as it appeared in 1968.

“There is, monks, that plane where there is neither extension, nor motion, nor the plane of infinite ether, nor that of neither-perception nor non-perception, neither this world nor another, neither the moon nor the sun. Here monks, I say that there is no coming or going or remaining or deceasing or uprising, for this is itself without support, without continuance, without mental object—this is itself the end of suffering.”

—Hinayana Selection

For the time being, very few addictive or “dangerous” drugs are used in Vietnam by American soldiers or by the communists. The only real exception to this is the package of dextro-amphetamine supplied by the United States Army in the survival kits given to soldiers in the field. It would not really be fair to call this drug “dangerous” in the amounts given, and their good service should be obvious to anyone ever having taken a “dexie” or any of the other amphetamine “pep” pills.

Opium in the Orient is a tradition in itself, and the carrying-out of that tradition is too time-consuming and elaborate for the average GI to bother with. It is also very incapacitating to the novice user. This is not the best condition to be in when confronted with an ambush, terror attack, or some like activity.

After opium, what remains are the fields and jungles of Southeast Asia, including Vietnam, which for thousands of years have been the natural home of the ever-popular Cannabis sativa, or marijuana. It has a more powerful brother known as hashish or kif or plain hemp. It is basically the same cannabis plant, but it is richer in resins, and thus in intoxicating tars when smoked or eaten. Unlike opium, which is a body drug rather than a mind drug, you can learn to function normally with marijuana. In the southern areas, the best of this plant comes from Cambodia, and the vast majority of “good stuff” comes across the border via the Ho Chi Minh trail, the same route made famous by the Viet Cong—a fairly romantic migration.

For the most part, the drug is cheaper and easier to find in Vietnam than a package of Lucky Strikes. It might be interesting to find out if the derivation of the R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company’s slogan, “I’d walk a mile for a Camel,” might not have come from the revered Arab expression, “A puff of kif in the morning makes a man as strong as a hundred camels in the courtyard.” In any case, marijuana is as easy to find in Vietnam as a Vietnamese national, and you needn’t find one to find the other.

Though the cities are full of the product, the deeper one goes into the countryside, the more prevalent this strange member of the tea family becomes. For the American, it is very unlike the stateside atmosphere for procuring the drug. There is no central market for it in Vietnam. It is simply a way of life. One has merely to stumble on his way outside an American billet to bump into a man who might be selling the plant. Or he may take a deep breath anywhere to smell its dusty aroma. It is the slightest of achievements for an American to “score” on more marijuana than he has ever seen in his life. “Score,” indeed. Who is it but the hotel maid or that friendly cyclo-driver who has been smoking it all this time, but he didn’t know it. When this realization finally strikes home (his attention being otherwise diverted by the fact that each day may be his last), the average soldier sees that for all intents and purposes the entire country is stoned. For the kid who has spent the last few years of his life going through much shoe leather and money, Vietnam is that huge garden he has always dreamed about. And to think, the Army sent him there.

The question comes up, “How many Americans in Vietnam smoke this ancient weed, and why, and when?” The answer, in order, is that most (seventy-five percent) young soldiers smoke it, for all sorts of reasons, all the time. This is a very hard statement to prove without actually asking men to admit to what their mother country maintains is a crime. However, some of the sociological backgrounds for this may help explain these vast numbers.*

Much furor comes up from time to time about the number of Negro soldiers serving in Vietnam: My purpose is not to comment on what truth there might be in the allegation that there are too many, per capita. Nor on the educational background of Negro GI’s. Nor on their draft status because of that educational background. Nor on their numbers on the front line and in combat, because of the lack of any other skills. Neither is it my purpose to discuss here just why they might not have had a proper educational background and the skills in the first place. It is my purpose, however, to make the obvious statement that they brought their personal joys and sorrows with them. Added to that they brought the implements, effects, and customs of what, for the most part, might have been a predominantly shabby environment…by the white soldiers’ standards. As any narcotics agent or Time-Life staff writer will tell you when not asked, the original marijuana traffic in America came out of the same parts of town that the colored boys have been caught in all their lives. Despite the fact that African dagga came over with slavery, the Negro soldiers’ predilection for “boo” is far more a matter of metropolitan geography than it is of color. If you can accept the facts already given, it is no huge feat of imagination to realize that the particular joy received in the smoking of marijuana has no stigma whatsoever while serving what might be their last moments in the land of limitless “boo.”

The colored soldier’s brother-in-arms is the white draftee. If you have been following the numerous reports of changing morals on the campus, and throughout the country, you are no doubt well aware of the moral, or at least the smoking, fiber of upwards of sixty percent of America’s educated youth. In fact, a Columbia University physician has said that “if a male goes through four years of college on many campuses now without the [marijuana] experience, this abstinence bespeaks a rigidity in his character structure and fear of his impulses that is hardly desirable.” Roughly the same percentage (sixty percent) of GI’s between the ages of eighteen and twenty-eight smoke, or have smoked, marijuana. Eighty-five percent or more of the true combat infantry and support elements fall within the eighteen to twenty-eight age group. And, of course; habits spread in the same way they do in any blood fraternity. Add to that the fact that it’s a hundred percent easier to get marijuana in Vietnam than on a stateside campus (where it’s very easy).

Until six or eight weeks ago, practically no civil or military controls were used in Vietnam to inhibit the smoking of marijuana, and it’s doubtful that the current furor will be very thorough or long lasting. This is not so much a matter of kindness though. It’s simply that with all its other problems, the military has neither the time nor inclination to try to jail such a huge part of its fighting force by stomping on marijuana, of all things. To enforce a prohibition against smoking the plant would be like trying to prohibit the inhalation of smog in Los Angeles. The military does not take as provincial a view of marijuana as American civilian law enforcement agencies do. In a reception room of a rest and recuperation center at Camp Zama, Tokyo, an Army captain offers to return all drugs to soldiers on their return to Vietnam. If they aren’t turned in, he advises the servicemen to keep them off their person while on the five-day stay in Japan because of the Japanese attitude about such items. He says that the girls in the Japanese bars that surround the Army post are given more or less a bounty by the Japanese police for every soldier they turn in for possessing drugs. Again he offers to return all narcotics and any explosives when the soldiers depart for Vietnam. To the best of my knowledge, the captain was true to his word when we left. (Pharmacists in the port of Hong Kong, another R&R center, sell all manner of barbiturates, and other prescriptive drugs, to military personnel without a prescription.)

The possession or use of narcotics is against Army regulations and is punishable under the Uniform Code of Military Justice. But as long as you follow orders and perform the job, you rarely have problems with the establishment. Marijuana does not seem to get in the way of either of these two mainstays of military order. In fact, marijuana does not seem to get in the way of anything except ignorance about marijuana.

Finances pose no problems for the troops in Vietnam who wish to buy the plant. First of all there is often nothing else for the bulk of front-line troops to buy. It’s up to the local commanding officer, but the majority of “up-country” PX’s will sell liquor only to staff sergeants and up. This means that a twenty-six-year-old corporal may not buy and drink what a nineteen-year-old sergeant may. It is possible to remain stoned on marijuana for the entire twelve-month tour in Vietnam for about fifteen dollars. If you become friends with a farmer or a mountain tribesman, there is no charge at all. But even though the availability of marijuana is so formidable, it is almost impossible for the most worldly city-minded newcomer to believe the stuff is all over the place. The memory of America and its controls are hard to erase.

The first time I left Saigon for an extended period, for example, I took a knapsackful with me, thinking I would have to go back to Saigon to get more when my unit had smoked it all up. Though we hoarded it among us, supposing we had something nobody else had, we finally ran out after a few months of isolation atop Vung Chau Mountain. We had nothing better to do. When the well ran dry, I was forced into a mercy mission to the local village.

I used the laundry at the bottom of the mountain as my base camp for the search and clear operation that I had been charged with by my fellow soldiers. The laundry, which was really just a village home, was owned by a wonderful drunken ex-Vietnamese soldier. He never did anything but laugh, and constantly hug us, his children, and his wife—as she did all of our laundry in their back yard. In payment for his constant good cheer and friendship, we would buy him beer at the PX in town. In payment for that, he would find the cleanest girls in the area to help share this beautiful circle of international good will. We loved him and traditionally called him Papa-san. Papa-san hated our first sergeant, who constantly bitched about the laundry because Mrs. Papa-san did such an awful job, but Papa-san’s feelings about the sergeant, in turn, erased our misgivings about the laundry and only served to enhance our love for his dear family and its many services to us. Our unit was the first group of GI’s he had ever had any close contact with.

On my search I spent weeks babbling and making smoking gestures at the people in the countryside, rolling my eyes to overstate my quest. At first they would seem confused, but then slowly, very slowly an idea would crystalize and they would run off with unbounded insight in their hearts. Invariably they came back with American cigarettes stolen from the PX. On some occasions it would be a pipe, or a Havana cigar, but always with that look of self-satisfaction that comes from complete understanding. After a hundred or more such incidents, I finally became totally depressed with my ability to communicate with peasants and went back to Papa-san’s to get drunk. He saw the state I was in and offered me his bed to lie in to help ease my burden. He seemed very distracted with my ill humor and discreetly left the little room while I searched my mind for feasible excuses to get me back to Saigon for a day.

About at the point where I had decided that I needed a new life insurance policy—a piece of paper work that could only be done in Saigon—Papa-san apologetically knocked on the door and meekly entered the room offering something that, if I tried it, might make things a little better. He had a lit pipe, and before he got ten feet away, I knew what was in it. I had just spent weeks going all over Qui Nhon, and here stood Papa-san, the main distributor of processed marijuana for practically the entire province. He thought we liked beer.

You now have a picture of the American fighting machine composed mostly of a group of youngsters enjoying the not-so-secret rites of cannabis. This is not far wrong.

The mass use of drugs in war is as ancient as war itself. The Vikings well knew the mind-expanding mushrooms. They would eat the fungus before battle for its mixture of inner calm and energy. The word “berserk” comes from the Nordic language to describe the state of enthusiasms achieved. Like this is the word “panic” used by the ancient Greeks, who, in worshipping the goat-footed god Pan, would partake of organic mind-drugs as well as wine. Despite this, it is inaccurate to think of the effects of these drugs causing an almost inhuman state of violence. When used as a sacrament, Skippy peanut butter could bring enthusiasms and group spirit. By themselves the drugs allow a certain amount of mental flexibility, and an almost spiritual easiness that can lead either lethargy or excitement. Suffice it to say that these drugs, including marijuana, bring a sort of ethereal happiness, and what acts are to be performed within the gates of this happiness are up to the individual. Marijuana for the most part leads to a calm, perceiving detachment.

Because of what marijuana does to the brain’s interpretation of light, and what we call beauty, a wonderful change in war starts to occur. Instead of the grim order of terror, explosions modulate musically; death takes on a new approachable symbolism that is not so horrible. All the senses, including the emotions, are muted by being hyper-charged with their own capacity. There is not time enough to delve into the unusual manifestations of fear with this entirely new lexicon of sights and thoughts to deal with. And the changes keep occurring. I well remember sitting on top of a bunker with about twenty friends during what we thought to be an attack on our mountain. It was about midnight. The South China Sea was behind us with an opaque moon spreading its glory out over the mixture of Navy ships and sampans in the harbor a mile below us in Qui Nhon. Their lights would twinkle back recognition of our appreciation. Many an oriental artist has tried to capture just such a scene. In front of us, in the direction of the supposed attack, lay the beautiful mountains and valleys of the central highlands. The blue-green rolling hills were studded here and there with volcanic boulders that shouted their blackness back at the stoned eyes that beheld them in the delicate moonlight. When the flares and fifty-caliber machine guns started up for cover, you could barely hear the noise of the ordnance over the ohs and ahs coming from our little group of defenders, smoking Papa-san’s grass. The beauty of all that gunpowder (an oriental invention, you remember) was almost too much to bear. Up would shoot a white star-flare on a parachute, and all eyes would be transfixed at the glow. Of course, it was intended to show whether the enemy was coming up our side of the crest, but a sigh of “did you dig that?” whispered past the shuffling of grenades and ammunition. The mutual feeling was, “If this is it, what a nice way to go.” The clatter of the machine guns was like a Stravinsky percussion interlude from “Le Sacre du Printemps.” There isn’t a psychedelic discotheque that can match the beauty of flares and bombs at night.

Everyone was left with the feeling that we were unique in this war to be seeing it from such a detached and esthetic vantage point. That was until discussion started up on the mountain after it was all over. Other Gl’s, when commenting on the action, or any action, would say, “Yeah, but you should see it when you’re high.” To have this social ploy stolen by a meager infantry type (we were radio and television specialists) seemed a great shame, until further investigation proved that virtually everyone was smoking “grass” before, during, and after the shooting. Not just on my mountain. Not just in my bunker, but on every mountain and bunker in Vietnam, by both sides.

Within the pressure of war, everyone was taking the release from war. Perhaps to many GI’s it was the only and last relief that Vietnam had to offer. Sometimes you would hear friends of a dead soldier say, “Thank God he was stoned.”

The valleys and mountains surrounding the now historic area known as Dien Bien Phu was, and still is, the largest opium-producing district in all of what was Indochina. For centuries the opium poppies have been milked by the mountain tribesmen who maintain the fields for the usual reasons. More recently, the proceeds from this natural drug were used by the Viet Minh to help finance their war against France. The raw opium was sold through the markets of the Orient to buy arms, and there is no reason not to assume that the practice still goes on under the auspices of the National Liberation Front. Of course today they get many of their pretty bombs and flares and tracers as gifts from sympathetic pyrotechnical supply houses such as the Soviet Union and Communist China, though it can pretty well be assumed that opium is still a supplemental source of income for the National Liberation Front. As I said before, an addictive drug is not the best thing to ingest when heavy exercise, such as shooting at people, is anticipated. Opium is a drug for old men in this part of Asia, and wealthy old men at that. However, hashish and marijuana are used extensively—again, not specifically for the purpose of war, but as a way of life. It is a sad coincidence that that life has seen nothing but war. Beyond this, marijuana and war should not be connected.

Betel is chewed by the majority of the peoples of Southeast Asia. It is one of nature’s amphetamines. It is more common in North and South Vietnam, and used more extensively, than tobacco is in the rest of the world. The mixture of nut, leaf, and lime that makes up the betel morsel causes the teeth to turn black, and everything else in the mouth to turn a reddish-orange. But you see, while the Vietnamese don’t really enjoy having reddish-orange mouths, they do enjoy the “buzz” it gives them. The chewing of the fruit of this palm gives the chewer energy, a sense of well-being, and calmness. It also gives him stamina and endurance. It becomes obvious that we use our drugs for the same reason.

In moments of contemplation in Vietnam, I began to wonder where the mystical Oriental had disappeared to. Oh, the silliness of the name-calling that was needed just to keep up suspicion and fear on both sides. As in all the wars before it, the opposing side had to be barbarians of a sort, and if they weren’t…why fight? Where to find the personal animosity? It seemed that political arguments would not be able to survive their own stupidity without first building the adversary into a fiend of the night. Once this was accomplished, man-to-man personal hatred could keep a war alive for centuries, and of course it has.

It has been well reported that Viet Cong and North Vietnamese troops use drugs in battle. These reports seem to have been designed to give them a sinister image of zombies or robots for a political machine that keeps them drugged to fulfill that government’s evil intentions and keep them slaves to the system. Anyone familiar with marijuana would have to laugh at this conception.

As I see it, there is very little difference between the state of mind of the stoned Viet Cong, and the stoned GI. The dead Viet Cong found with drugs on his person resembles in every way the American dead found with drugs. If the GI also has his survival kit with him containing all those dextro-amphetamines, who looks worse, and whose government is supplying whom, with what? It is very likely that the Communist got his little bag of boo from the wife before he left the tunnel that morning.

To make him look more uncivilized, the Viet Cong sometimes wields a little musical instrument called a bugle. He may even be tempted to toot it as he runs along. We don’t seem to find much harm in the Scottish bagpipes or the thrill of a rebel yell. After all, any child knows that he can relax when the cavalry starts sounding off—and yet, down on our imagination comes a fanatic band of junkie Orientals with their pajamas on, slit eyes, and reddish-orange mouths, howling like wolves with bugles blaring. What hath God wrought? From a purely public relations standpoint, it would be interesting to see what Americans would have done to besmear the ancient Britons who had the nerve to paint themselves blue in combat. For that matter, I wonder what the ancient Britons would have thought of an American Army sergeant climbing on a troop plane in Pleiku with six human ears on a wire on his belt. I wonder if he would stop to consider the sergeant’s “civilized” motives before he filed his press release.

To take this line of reasoning to the extreme, the chains that have been found binding Viet Cong gunners to their weapons serve a very basic psychological purpose when washed with the same intellectual detergent that we use about napalm and gas in Vietnam. Once a man knows that he has no other way out than victory, he can devote all his attention to that end. The Viet Cong sometimes bind themselves with chains as a gesture of determination for their comrades, a gesture not unlike the signature on a marriage contract or the death penalty for desertion and cowardice that can be enforced under the United States Army’s Uniform Code of Military Justice. I wish I knew the translation for “We have not yet begun to fight” in Vietnamese. Congress will give a man’s wife a medal because he threw himself on a hand grenade to save the lives of the men in his squad. If it had been a Viet Cong, it probably would be reported as an act of fanaticism by an individual probably hypnotized with drugs, or with fear of reprisals on his family, or oriental suicide. If the American and Communist soldiers are both taking drugs as they face each other for the kill, is it any stranger than if they weren’t?

The parallels tend to get a bit broad, but why not, considering that two armies, intoxicated and mentally staggering through the jungle, may be being sent out to dance to this ghastly libretto by government leaders and officials all suffering from quite a different “high” of their own? The quality of that high is one that neither of these two combattants could begin to guess at…straight, or stoned, themselves.

This is what they call modern warfare, guerilla warfare, pacification, liberation, oppression, suppression, repression, or perhaps self-deception. Deception to the point that the cogs on both sides have retreated by smoking or chewing their happiness in the face of it all.

Many nights, playing just such a role in it all, I would listen to the night, trying to figure out what it was all about. The quality of this kind of search is no different whether it be on a presidential rocking chair or in a foxhole. I was very happy that because of a few plants, Americans and Viet Cong alike didn’t have to bear the naked weight or other people’s decisions and foregone conclusions. At least they had the buffer of their mind—its happiness, its desires, its woes, and giving—these textures that would always remain untouched by leaflets or campaign speeches, or bullets, or horror. This part of the mind was in itself an area of peace into which no one might trespass: a hallowed garden of thought that could be maintained even in the face of all calamity. I would play a game in my head which I will pass on to people in a less picturesque setting. It was a game of bitter equations:

If you can, picture the armies at their own game on opposing sides of a table. The fact that there is a game at all is supported by their suspicions and affirmations about each other. The feelings, beliefs, and motivations of the Viet Cong are no less pure than ours because of their proximity to the table. The gestured manifestations of their humanity, their way of life, are no more or less immoral or atrocious than the American considers his. The game progresses, and the game gets worse. There is no final score other than what can be measured in mutual loss. The outcome finally comes down to being on the right or wrong side of the table.

Now picture the entire tableful of men, each hidden in the playings of his mind by this strange plant. No, not one of them is really very involved with the table at all. They all seem to be acting out someone else’s conviction, someone else’s hate. Look closely and see if it isn’t just a little bit yours.

“There is, monks, an unborn, not become, not made, uncompounded, and were it not, monks, for this unborn, not become, not made, uncompounded, no escape could be shown here for what is born, has become, is made, is compounded. But because there is, monks, an unborn not become, not made, uncompounded, therefore an escape can be shown for what is born, has become, and were it not, monks, for this .. . “

* EDITOR’S NOTE: In fact, preliminary reports on an official Army study show that eighty-three percent of soldiers questioned said that they had smoked marijuana. And on the same day that the chief U.S. information officer in Vietnam was calling Specialist Steinbeck’s statements ridiculous, the provost marshal in Saigon said that more servicemen are arrested for smoking marijuana than for any other offense. A new crackdown followed numerous press reports of this article, and a larger Army investigation has been launched.