The expanding universe of thrillers—private-eye novels, serial-killer sagas, legal narratives, spy stories—is increasingly site-specific. Writer and hero stake out their turf and explore it in book after book. Raymond Chandler once owned Los Angeles; now it belongs to Michael Connelly. Ed McBain claimed New York City with his 55 novels about the 87th precinct. John D. MacDonald’s Travis McGee will forever patrol the blue waters of Florida.

But who are Washington’s McGees and McBains? Things here are diffuse: Private eyes, spies, crusading lawyers, and presidents are all caught up in the mix.

The best Washington crime writer at work—and one of the three or four best in the world—is George Pelecanos. If Washington has produced a great private eye, he is Pelecanos’s Derek Strange, the hero of four novels—Right As Rain, Hell to Pay, Soul Circus, and Hard Revolution—that offer an uncompromising look at life in black Washington. Because Pelecanos feared that an extended series might sap his creativity, he has put Strange on the shelf and moved on, notably to last year’s excellent cop novel, The Night Gardener. No matter. Anything Pelecanos writes is worth reading.

In another corner of fictional Washington—and of the entire literary universe—is Tom Clancy, who in a series of best-selling military thrillers elevated his hero, Jack Ryan, from history professor to CIA agent to vice president and finally—thanks to fictional terrorists who crashed a hijacked plane into the US Capitol well before 9/11—to president.

If you share Clancy’s conservative views—he is, to me, essentially a political novelist—the Ryan novels are impressive. We all long for a brave and wise president who will protect us from the world’s evildoers; for Clancy and his fans, Jack Ryan was the man.

The CIA has inspired some first-rate spy thrillers. The action in these novels fans out all over the world, but the spies always come home for briefings at Langley, cocktail parties in Georgetown, and trysts in Spring Valley. Three novelists in particular offer insights into this city as well as into the mysteries of tradecraft.

Charles McCarry is the most venerated; his Paul Christopher novels are dazzling fiction, particularly The Tears of Autumn, his elegant meditation on the John F. Kennedy assassination. His recent Old Boys offers some nice Georgetown scenes as several of Christopher’s over-60 colleagues plot to free their brother spook from a distant prison.

I have equal admiration for Robert Littell, who since 1973 has produced 15 novels that cast an extremely cool eye on the CIA. My favorites are The Defection of A.J. Lewinter, about the Cold War; The Sisters, on the JFK assassination (though he’s never mentioned by name); and Legends, about a CIA agent who has had so many identities that he no longer knows who he is.

In 2002 Littell published a realistic novel, The Company, which takes a 40-year look at the CIA’s role in the Cold War, mixing fictional characters with real-life figures such as crazed Red-hunter James Jesus Angleton and British traitor Kim Philby. If you’ve forgotten how cynically our government encouraged and then abandoned the Hungarian freedom fighters in 1956 or what a fiasco the 1961 Bay of Pigs invasion was, The Company will bring history vividly to life.

As the Cold War ends—and the novel with it—two agents, one a spy called the Sorcerer, reflect on their victory:

“ ‘It was about the good guys beating the bad guys,’ Jack said softly.

“The Sorcerer snorted. ‘We sure screwed up an awful lot in the process.’

“ ‘We screwed up less than they did. That’s why we won.’ ”

DC novelist Daniel Silva—before he began his popular series about Israeli art restorer and spy Gabriel Allon—published two polished thrillers about CIA agent Michael Osbourne. In The Mark of the Assassin, terrorists use surface-to-air missiles to bring down a commercial airliner off the coast of Long Island; this plot was suggested by the 1996 crash of TWA Flight 800. The Osbourne character investigates the disaster and is soon battling powerful forces in Washington.

Next came The Marching Season, which pitted Osbourne against both IRA terrorists and a Washington-based conspiracy of right-wing politicians and arms merchants. Silva’s was a dark view of sinister forces at work in Washington, and in time he decided he’d be happier writing about an Israeli spy’s adventures in Europe.

In addition to these known names are some lesser-known authors who have written well about Washington.

Ross Thomas was 40 when he published his first novel, the Edgar Award–winning The Cold War Swap, in 1966. Before that, Thomas had roamed the world as a foreign correspondent and political consultant. Some of his friends suspected a CIA connection; if so, Thomas wasn’t much impressed by the agency, as he would prove in two dozen more novels he published before his death in 1995.

The books were sardonic and entertaining, often featuring wonderful titles—The Fools in Town Are on Our Side; If You Can’t Be Good; Chinaman’s Chance (which features the inimitable Artie Wu, con man and pretender to the Imperial Chinese throne); Missionary Stew; Briarpatch (another Edgar winner); and his last, 1994’s Ah, Treachery.

Thomas’s novels are set all over the world—a political campaign in Africa, small-town corruption in the United States, CIA incompetence everywhere—but there are lots of local connections. Chinaman’s Chance, for example, features a skirt-chasing congressman who dies mysteriously, possibly murdered by his wife.

Thomas lived here for a time and met his wife when he was doing research at the Library of Congress and she was on staff there. He never received the recognition he deserved, although he is greatly admired by other writers. Most of his books remain in print and are worth seeking out.

When Thomas started publishing in the mid-1960s, his caustic view of American politics was a bit ahead of its time, but in the 1970s the national trauma caused by Vietnam and Watergate injected a massive dose of cynicism—some would say realism—into political fiction. Thrillers became darker and more ambitious.

In Washington writer James Grady’s first novel, Six Days of the Condor (1974), rival factions in the CIA are at war. The political stakes are even higher in my favorite of the Nixon-era novels, Edward Stewart’s They’ve Shot the President’s Daughter, which I reviewed in 1973. I was intrigued by its title and hooked by its black humor.

Stewart’s novel presented a Nixon-style president who would stop at nothing to seize dictatorial powers. I won’t reveal how he tries to do so, but the title pretty well gives it away. It’s a scathing portrait of political corruption. Philip Roth’s Nixon satire, Our Gang, was published at about the same time, but Stewart wielded the sharper hatchet.

Among the Washington-related thrillers I’ve reviewed in recent years, three stand out.

Stephen Horn is a former Justice Department prosecutor, and his Law of Gravity is a smart mix of legal thriller and sophisticated political novel. The plot turns on one fact: A presidential campaign is in progress. To Horn, this means anything is possible, including homicide.

Senator Warren Young is the front-runner for his party’s nomination until one of his aides disappears in a possible case of espionage. Philip Barkley, a Justice Department lawyer, is asked to “investigate” the case but is expected to deliver a whitewash. He balks and is fired but continues his investigation.

The political novel becomes a thriller as witnesses turn up dead and Barkley finds assassins on his trail. Law of Gravity is finally a novel about an honest man confronting a corrupt political establishment.

In one quite realistic moment, Barkley describes a confrontation between a career lawyer at Justice and the new US attorney general:

“I’d witnessed this scene dozens of times in the White House and the Senate: newly appointed or elected officials being deviled by bureaucrats who didn’t seem to grasp political reality.”

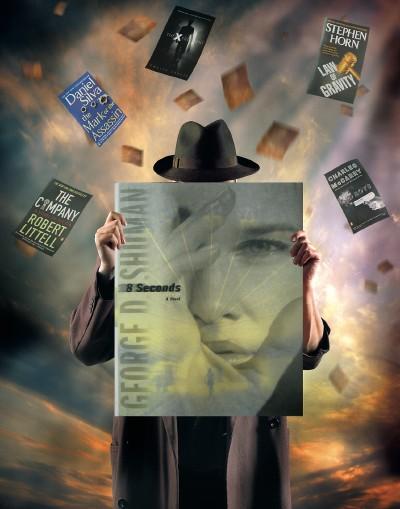

George D. Shuman spent 20 years as a DC police officer, advancing from undercover narcotics investigator to lieutenant commander in the Internal Affairs Division. Last year, after his retirement, he produced 18 Seconds, an unusually well-written first novel.

The book isn’t set in Washington, but I suspect that lessons Shuman learned on the streets here inform his taut story about the search for revenge, a female police lieutenant in a New Jersey seaside resort, a scary serial killer who targets women, and a blind woman who has the power to glimpse the last 18 seconds of a dead person’s life.

When the book came out, some were reluctant to believe that an ex-cop could write a novel that was more than passable. But talent has a way of cropping up in unexpected places. Shuman plans to put his DC years to use in a forthcoming novel about a local Drug Enforcement Administration agent.

Another example of talent in an unexpected place: Philip E. Baruth is an award-winning commentator for Vermont Public Radio, and his The X President is one of the oddest political novels ever written. It’s part politics, part science fiction, and all pleasure.

The story begins in 2055, when it looks like curtains for the United States. At home, the Allied Freemen’s breakaway republic controls Nevada, and its forces shoot down government aircraft. Abroad, Sino-Soviet armies are poised to invade the US mainland. At this dire moment, the National Security Council realizes that only one man can save America.

He is Bill Clinton, who at age 109 is still at his presidential library in Little Rock, working on the authorized biography that will salvage his reputation.

As president, Clinton had pursued high-minded antismoking policies that, thanks to the law of unintended consequences, led America into this mess. Now, because of a breakthrough in time travel, the NSC can send emissaries back to the 20th century to ask the younger Clinton to reject the policies that brought us to the brink of catastrophe.

All of this is narrated by comely Sal—for Sally—Hayden, Clinton’s book collaborator. Clinton is a wreck, kept alive and mobile by various medical miracles, but he maintains his charm and guile. At one point, he warns Sal to leave the door open when she’s in his office lest people talk.

Sal first returns to 1963, where she seeks out the 16-year-old Clinton, in Washington on the Boys Nation trip that led to his celebrated handshake with President Kennedy. Clinton—a sucker even then for a pretty face—eagerly agrees to help save his country from losing World War III some 90 years later.

The X President pleases in many ways, but nowhere more than in its portraits of Clinton: as a teenager, as president, and in old age. Baruth doesn’t ignore Clinton’s dark side—“The curse is this: BC’s acts are his, but his consequences are yours”—but he understands his charisma, too.

Books like The X President add new dimensions to fiction. Essentially, the book’s plot is the same as several of Tom Clancy’s novels—a president tries to save America—but it’s much more imaginative.

The old-style Washington novel, as pioneered by writers such as Allen Drury (Advise and Consent), has pretty well died out because so many were the same. Imaginative books like these—by writers as diverse as Pelecanos, Littell, and Thomas—can make you see this town in new ways that amaze and delight.