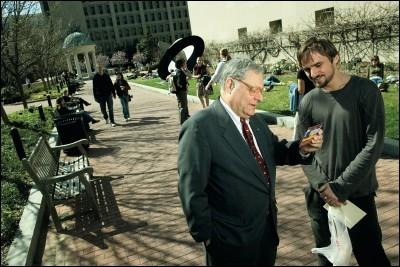

Stephen Trachtenberg retires this summer after 19 years as president of George Washington University, and he’s looking ahead to July 31: “I’m making a list of people I’m going to pardon the day I leave.”

It’s the sort of quip to be expected from Trachtenberg, 69, who grew up in a middle-class Jewish family in Brooklyn and is a fan of comedians Jackie Mason and Jerry Seinfeld. But it also hints at the tension that has come from a long tenure running an institution that—with nearly 20,000 students and 8,000 employees—is the District’s largest private employer. The average tenure of university presidents is just over eight years.

Trachtenberg’s parents stressed education; when the young Trachtenberg scored 98 on a high-school exam, his father asked him who had gotten the other two points.

Trachtenberg received a degree in American history from Columbia, went on to Yale Law School, then got a master’s in public administration from Harvard.

He had a couple of jobs in Washington: He was an aide to Indiana representative John Brademas and worked for Harold Howe, commissioner of education in the Johnson administration. He became an associate dean at Boston University in 1968, was named president of the University of Hartford in 1977, and succeeded Lloyd Elliot as GW’s president in 1988.

Two decades have been long enough to make big changes at GW. The university now is more selective, admitting 37 percent of the nearly 20,000 who apply, compared with 78 percent of 6,400 applicants in 1988. The growth in the pool has come despite the fact that tuition, room, and board are now more than $50,000 a year.

The full-time faculty has grown by 50 percent to 1,500, financial aid has risen to $188 million a year, the endowment has grown from $200 million to $1 billion, and a lot of money has been spent dressing up the Foggy Bottom campus with landscaping, sculpture, flags, and plazas.

During Trachtenberg’s presidency, the university acquired the campus of Mount Vernon College on DC’s Foxhall Road, opened a campus in Loudoun County, and bailed out its aging, money-losing hospital by creating a partnership with a private company that made possible the building of a new hospital.

GW is now ranked by U.S. News & World Report as the country’s 52nd-best national university, and its men’s and women’s teams make regular appearances in the NCAA basketball tournament.

Upon retirement, Trachtenberg and his wife, Francine, will move out of the GW president’s residence in DC’s Kalorama neighborhood to a home they’ve bought around the corner. She has retired as a senior executive with WETA but is active as president of the board of the Washington DC Jewish Community Center. They have two sons—Ben, a lawyer in the New York City office of Covington & Burling, and Adam, who lives in San Francisco and is a senior manager with eBay.

Trachtenberg is retiring with a GW professorship and plans to do some teaching, writing, speaking, and consulting. His “irreverent memoir” will be published later this year.

Why should a high-school senior choose GW over Georgetown?

Both institutions are terrific, but we’re a scrappier, more underdog place.

I think Georgetown students tend to be a little complacent. They think they’ve gotten where they’re going in life the day they get admitted to Georgetown.

What’s a university president’s hardest job?

There’s a temptation for every unit in a university to maximize its own interests, so it’s sometimes difficult to pull all these people together to work toward a common goal. You want the dean of the law school to be an advocate for the law school. You don’t want him to be so blindly committed to that goal that he’s prepared to close down the rest of the university and use it to feed the ambitions of the law school.

This is a very difficult thing in universities—trying to make people at the medical center understand why it’s important to them that the history department flourish. You spend a lot of time as a president explaining, trying to articulate a vision that people will come together about. And you’re doing it in an environment in which individual achievement is celebrated.

University presidents have very little actual power to command behavior. They have lots of room for persuasion and commentary and critique, but they have to bring people along.

It’s important to remember that many of these people have lifetime contracts. Once you give a professor tenure, you’ve got that woman or man for the balance of his or her natural life. So it’s through argumentation and intellectual seduction that people come around. That’s very daunting because they pride themselves—in general, rightfully—on their powers of analysis and commentary. The president is merely the chief clerk.

What traits are needed in a college president?

Persistence is very important. I’ve been able to get some useful things done at GW because I’ve stayed and worked at it. I get satisfaction from coming to a university, giving it a decade—in this case, almost two—and being able to have a vision and carry it forward a chapter at a time, a building at a time, a program at a time.

Listening is highly underrated. I’ve come to have a greater respect for keeping quiet. This isn’t always apparent to my friends and colleagues, so I want to point out that Albert Einstein taught us that things are relative. What may not seem like listening on my part might be.

Are U.S. News rankings useful?

It’s always useful to have some sort of external, allegedly data-driven measure of how you’re doing. On the other hand, there’s something simple-minded about the U.S. News rankings, which try to reduce complex issues to a basketball score. You can’t compare colleges in that way—it’s just not that simple.

Is it better for a student to go to a very fine, small university in some rural environment or to come to a university in downtown DC or Manhattan? It depends on who they are and what they want. There are kids for whom George Washington University is the best, and there are others who ought to go to some small liberal-arts college, then come to us for their law degree. People mature at different rates; they want different environments.

Still, it’s always stimulating to have some guy putting a rabbit on the track and getting you to run after it. We’re a little like greyhounds at the dog races. All American universities love to be praised in public. We’re all a little competitive, and we’re all out there running after it.

Used appropriately and in moderation, the rankings won’t do any observable harm.

How have students changed since you were a dean in the 1960s?

Students are still 18-year-olds and have the same issues their parents and grandparents had. Eighteen is tough. There are all kinds of issues about God and man, men and women, what am I going to be when I grow up, I’m giving up being a child and becoming an adult. It’s angst and experimentation. I’m not sure they have enough of a base of experience for all the freedom they’ve got, and that creates anxieties.

I find our current students bright, attractive, committed, and hard-working—much more charming than students were when I became a dean. Back then, there was a tremendous tension between the generations.

One of the Ten Commandments is “Honor thy father and mother.” There must have been a problem with young people not honoring their father and mother, which is why the Lord put that injunction in. So there’s nothing new in that. Generation gaps go back to biblical times.

I suspect our children will have the same experiences when they become parents. My mother always used to say, “Stephen, I hope when you grow up you have children just like you.” That was her curse.

How strong a force on campus is political correctness?

You have to be thoughtful about the things you say. You can create great pain for people if you say things that step on their sensitive spots. On the other hand, to be as constrained as people have been in the last few years is also artificial.

We’ve gone through a period of severe political correctness, but I think most people have integrated the issue in their minds, and now there’s an easing back. We’ve seen where it’s gone too far, with speech codes on some campuses. I think you’re seeing a restoration of balance.

Even now, I find myself balancing my “he’s” with my “she’s” when I speak and making sure I’m gender-neutral because I don’t want to hear from my wife about it.

You can actually make jokes now about political correctness. As somebody who frequently gets right up on the margin, it’s a bit of a release to me to have more freedom of speech.

Why are professors and presidents sometimes at odds?

The culture of faculty members is to focus on their disciplines. They’re biologists, historians, or chemists first. They’re university professors second. And they’re professors at GW third.

More than almost anything else, most professors care what other professors think of them, what kind of reviews their books are getting from other faculty in their discipline. These professors are referred to in the literature as “cosmopolitans.” There’s a cohort of faculty who care about their own university, but it’s small. They’re generally referred to as “provincials.” As the university becomes more of a research university, you see more cosmopolitans and fewer provincials.

The result is that getting a group to sit down together and think about positive initiatives on behalf of the university as a whole is frequently daunting. Change is hard because people have made some sacrifice to get themselves into this fraternity called the professoriate. They’re generally making less money than they could in other walks of life. They like being professors, which means they don’t want the situation to change. If you come along and say we have to work longer, we have to work harder, we have to work differently, they don’t want to know about that.

Why so much tension between GW and neighborhood residents?

I don’t think it’s any worse at GW than it is between Columbia University and Morningside Heights, NYU and Greenwich Village, Harvard and Cambridge. It’s very hard to have a large institution, whether a hospital or a university, next to another community and not have a certain amount of friction.

I think we get a bad rap. We’re constantly looking for ways to be nicer and warmer and of service to the community. We don’t get enough credit for the positive economic effect we have on the city or how diligent we are about providing services and safety.

We’ve been in the Foggy Bottom neighborhood since 1912. Unless the people complaining about us are very, very old, chances are excellent that they moved into Foggy Bottom after we were here. They should have anticipated waking up one morning to find that the university was here.

Your most important accomplishments?

When Mount Vernon College, in upper Northwest DC, found itself in financial difficulty, we were able to arrange a transaction that resulted in its becoming Mount Vernon College of George Washington University. That gave us facilities that allow us to have several hundred more students. It gave us an alternative campus that has woods and green space as well as playing fields for both men’s and women’s teams.

We’ve been transformed academically. When I came, we had 6,000 applications for roughly 2,000 seats. Today we get close to 20,000 applications for 2,300 seats. We get better students, and we get students for whom GW is their first choice.

We also get the faculty we want. It used to be you’d have to make four or five offers to get a professor to fill a seat. Today we pay our faculty right, and we give them the resources they need. So we get our first choice a lot, and they stay when we want them to.

GW feels good about itself. People walk around the campus and say this is an aesthetically reinforcing and pleasing place. People are proud to be associated with George Washington University. That’s true of alumni and current students.

How has GW’s location in the nation’s capital affected your job?

Last week I had the privilege of going to Vice President Cheney’s house for cocktails, and the next night I had dinner with the ambassador of Kazakhstan. You play a role here as a representative of higher education to both the federal government and the international community that a university president doesn’t in Cleveland or Chicago or Syracuse.

What have you learned about life?

Take it just seriously enough but not too seriously. You have to be able to laugh at yourself and keep other people laughing in the darkest of days. Stay optimistic.

You have to be patient. Institutions have a tensile strength, and if you bend them too quickly, they may break. But if you’re prepared to be slow and steady, you can frequently get them to come around.

You’ve got to be prepared to invest your life in an institution to change it. Being president of GW has taken 20 years of my life. On the other hand, it’s repaid me by giving my life meaning that I don’t think I could have had almost anyplace else, as well as extraordinary friends and colleagues. And it allowed me to bring up my children and have a wonderful family. So it’s been a quid pro quo that I’m the ultimate beneficiary of.

Senior writer Larry Van Dyne first covered Stephen Trachtenberg in the late 1960s when Trachtenberg was a Boston University dean. Van Dyne’s profile of him as president of GW appeared in the March 1999 Washingtonian.