Martha Pennino moved to Vienna in 1956 when her husband, Walter, a decorated Army veteran of World War II and Korea, took a Pentagon job. Farmland covered much of Fairfax County, which was home to about 100,000 people and enough cows to make it one of the state’s largest dairy producers.

Pennino plunged into politics and in 1967 won election to the Fairfax Board of Supervisors. For the next quarter of a century, she played midwife to Fairfax’s emergence as a booming metropolis, helping to give birth to such regional anchors as George Mason University, the Dulles Toll Road, and the town of Reston.

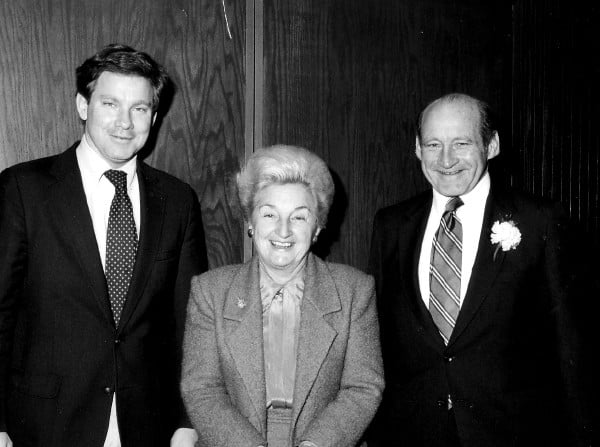

By the time Pennino left office in 1991, she was known as Mother Fairfax. A tiny woman made larger than life by her blond beehive and sunny disposition, Pennino charmed everyone.

Everyone, that is, except state legislators. She frequently went to Richmond to advocate for the region only to meet opposition from downstate lawmakers, some of whom sneered at what they called the “people’s republic of Northern Virginia.”

On one occasion she testified before a committee headed by 69-year-old Edward Willey Sr., the irascible Senate majority leader and elder statesman of the state’s conservative Democrats. Willey didn’t see much to like in Pennino’s plan to make Reston the state’s first “chartered community,” with its own elected officials and the power to levy taxes.

Northern Virginia, he told her, had to learn its place. “It just bothers me,” he said, “that you’re always coming up with something special up there, and what we’ve already got isn’t good enough.

“I’m not trying to be ornery,” he added, “but somebody down here has to put the brakes on.”

After more than a few such trips, Pennino’s frustration boiled over. “Madam chairman,” she announced at a Board of Supervisors meeting, “I’d like to suggest that we secede from Virginia and become the 51st state.”

Pennino, who died in 2004, was only half serious when she issued her call for independence in the 1970s. But in the years since, Northern Virginia officials fed up with Richmond have talked often of rebellion. No one has filed legislation to partition the state—politically, that would be nearly impossible. But the idea has lots of appeal.

For starters, Virginia is too damn big. With 7.7 million people, it’s the 12th-largest state. Its westernmost tip at the Cumberland Gap is a seven-hour drive from McLean—and it reaches farther west than Detroit.

Aside from the taxes it pays, Northern Virginia is arguably part of the state in name only. Robert Lang of Virginia Tech’s Metropolitan Institute says Northern Virginia has become an extension of the urbanized Northeast corridor. The region is so different from the rest of Virginia, it’s as though the New Jersey suburbs were grafted onto South Carolina, Lang says.

About a third of Virginians—21⁄2 million of them—live in the state’s 15 jurisdictions that are part of the official Washington metro area. Many are Yankee transplants who care little for state icons, whether Patsy Cline or Pat Robertson.

The two Virginias might coexist peacefully if not for the state legislature’s history of hostility and indifference to the north. Harry F. Byrd—the apple grower who became one of the 20th century’s greatest machine politicians—rigged the lawmaking game against Northern Virginia. Even today, 40 years after his death, the state steers lots of Northern Virginia’s tax dollars to downstate rural areas.

Richmond’s slights infuriate Northern Virginia. The region is one of the most economically dynamic in the country, if not the world. It’s a center, along with Silicon Valley and the Boston suburbs around Route 128, for what some scholars call the “creative class”—the scientists, engineers, artists, educators, and professionals who drive the “knowledge economy.” Eight Fortune 500 companies are headquartered in Northern Virginia—more than in 31 other states, including Maryland. If it were to secede, the new state would be the country’s most affluent and best educated.

“There’s a running joke that if you take Northern Virginia out of Virginia, you get Arkansas,” says Stephen Fuller, director of the Center for Regional Analysis at George Mason University. “That’s a little bit unfair, but not wholly.”

Geographically, Northern Virginia isn’t all that big, encompassing 7 percent of the state’s land area. Yet it’s an economic juggernaut that accounts for almost half the state’s economic growth, more than half its new jobs, and nearly half of income-tax revenues.

Yet to hear Northern Virginia officials tell it, Richmond doesn’t give the region a fair shake. Too few of the tax dollars sent to Richmond find their way back, they say. According to some estimates, Northern Virginia gets back only 25 cents on the dollar in cash and state services. Legislative experts put the figure closer to 40 cents or higher. But there’s no doubt that the region gives a lot more than it receives.

“They treat us like the Bank of Fairfax,” says one county official.

Nearly 200 years ago, counties in the northwest corner of the state felt similarly betrayed by Richmond. Apportionment in the legislature was based on a population count that included slaves—a provision that gave plantation owners in the eastern half of the state a big advantage over small farmers scratching out a living in the Appalachians.

The western counties won a few concessions, but eastern aristocrats kept the upper hand. State money and services flowed to eastern Virginia while only trickling to the west.

Then in April 1861, days after Fort Sumter, Virginia’s leaders voted to leave the Union. The state’s northwest area opposed secession and within months moved to free itself from Richmond. A new government was formed; elections were held for a governor and representatives to Congress. In 1863, Abraham Lincoln welcomed into the Union its 35th state, West Virginia.

Culturally, economically, and politically, Virginia has again become two states. The question for Northern Virginia is this: Why not secede?

On a warm August evening in the town of Galax in southwest Virginia, the sun is slipping behind tree-covered hills. It’s the second day of the 73rd annual Old Fiddlers Convention, which the host, Lodge No. 733 of the Loyal Order of Moose, says is the oldest and biggest in the world. Each year, in a park off Main Street, as many as 50,000 people gather to hear musicians from all over the world but mostly from the mountains of Virginia, North Carolina, and Tennessee.

Tonight features competition in the fiddle, dobro, and mandolin. Harold Mitchell, brother of Galax (pronounced “Gay-lax”) mayor C.M. Mitchell, handles the emcee duties on the park’s wooden stage, his drawl and cowboy hat complementing the music: “Here’s contestant number 101, Jennifer Bunn, playing ‘Squirrel Heads and Gravy.’ ”

Former governor Mark Warner, the Democratic candidate to replace the retiring Republican John Warner in the US Senate, is due on stage later. At first, one might wonder what Warner would have to chat about with folks here. A Harvard-trained lawyer, he made millions in tech ventures; parts of southwest Virginia only recently got high-speed Internet access. The property taxes alone on his $6-million Alexandria home are more than the average Galax family makes in a year.

During his 2001 gubernatorial campaign, Warner showed up at the fiddlers convention in a polo shirt and pressed jeans—“like he’d just left the country club,” Matt Bai, a writer from Newsweek, told Warner aides Dave Saunders and Steve Jarding for their book, Foxes in the Henhouse. “I think I actually cringed.”

Warner credits his win that year to his barnstorming through southwest Virginia and Southside, the rural region from south of Richmond to the North Carolina border. The candidate sponsored a NASCAR team, and the campaign wrote a bluegrass theme song that opened, “Mark Warner is a good ol’ boy from up in Novaville.”

The line got laughs, but growing tensions in the state can make association with suburban Washington a political liability. Longtime Northern Virginia politician Leslie Byrne, who campaigned statewide for lieutenant governor in 2005, says, “I feel like I have a big nova embossed on my forehead. There’s a great deal of mistrust and resentment of Northern Virginia in the rest of the state. They think we look down on them, that we’re better than the rest of them.”

Virginia isn’t the only state where regional rivalries threaten the peace. There’s bad blood between Chicago and downstate Illinois, between Baltimore and DC’s Maryland suburbs, between Northern and Southern California. In the 1970s New York City mayor John Lindsay, Norman Mailer, and Bella Abzug campaigned to turn the five boroughs into the 51st state.

In a 2006 satire, Washington Post Style writers catalogued the differences between “NoVa” and what it called “RoVa,” the rest of Virginia.

“In NoVa, a ‘fur piece’ is something a woman wears on a special occasion. In RoVa, a ‘fur piece’ is a unit of distance.

“In RoVa, they like freshly killed venison. In NoVa, they like Alfred Lord Tennyson.”

The truth is, Virginia is the least Southern of the Southern states save Florida. Nor is Virginia a hillbilly haven. Seven of ten residents live in metropolitan areas, whether in Northern Virginia, Richmond, or the Tidewater area.

Still, major parts of the state are known for tractor pulls, motorbike racing, conservatism, or other staples of Southern culture. Jerry Falwell’s Liberty University in Lynchburg, the world’s largest evangelical university, enrolls 20,000 students, making it about the size of the University of Virginia.

Racism occasionally flares. At the fiddlers convention, a few Confederate flags fly over the sea of RVs that house performers. A man who notices a Warner aide with a Barack Obama button says to me: “I hate blacks—all of them.”

The Northern Virginia suburbs began to pull away from the Old South decades ago. As the federal government swelled during the New Deal and World War II, newcomers poured in from all over the country. Major corporations set up headquarters here after Mobil Oil’s 1987 move from Manhattan to Fairfax. By 1990, half of Virginia residents were born outside the state, with most of the transplants landing in Northern Virginia.

The rest of the state didn’t take well to the new arrivals, says Til Hazel, the Northern Virginia lawyer and developer who helped create Tysons Corner. “You gotta realize, Virginia is a very proud and old state,” he says. “It’s a place where tradition and family values mean a lot. Things like when you got to Virginia, who was your grandfather—they mean a lot to people.

“I don’t like saying this, but it started with the fact that ‘they’re not like us.’ ”

In Richmond today, two-thirds of the residents were born in Virginia. In Alexandria and Arlington, natives are outnumbered by transplants four to one.

Northern Virginia has become the sunbelt of the Northeast, says Virginia Tech’s Lang, drawing from places such as New York and New Jersey—states that couldn’t be more different from Old Virginia.

The flood of immigrants to Washington from abroad sharpens the divide. More than 20 percent of Northern Virginians were born in another country, compared with 3 percent in the rest of the state.

While Robert E. Lee fought for the South out of loyalty to Virginia, newcomers aren’t likely to think of themselves as Virginians. Many work for tech companies that look and feel like Silicon Valley. They pay more attention to Capitol Hill than to Richmond.

Northern Virginia’s lack of kinship with its neighbors to the south is a sore point. The Fredericksburg daily newspaper urged a “forced secession” of Northern Virginia a few years ago (even though Fredericksburg is technically part of the Washington metropolitan area).

In an editorial, it said that Northern Virginia residents “are more Northern than Southern and are far more at home with their neighbors in the Maryland suburbs than rural Virginia. . . . They speak a different language than the rest of us. Their values are different. They seem to want only bigger houses, more educational degrees, and less freedom. They want their children to study, not play, and they seem to delight in sitting in parked cars along freeways for hours at a time.”

Cultural tensions are exacerbated by disparities in wealth. Northern Virginia is the richest region in the country. Nielsen Claritas, which analyzes consumer markets, ranks Fairfax City, Falls Church, and Fairfax County among the country’s five jurisdictions with the highest concentration of what it calls the “upper crust”—suburban couples likely to drive Jaguars, read the Atlantic, and spend $3,000 or more a year on foreign travel. Manassas Park tops the Nielsen ranking for families in the “winner’s circle,” where the median income tops $100,000 and there’s an Infiniti SUV in the driveway.

The rest of the state is not poor on the whole, but the gap in wealth is big. Average annual household income tops $90,000 in ten of Virginia’s 134 jurisdictions; nine are in the Northern Virginia suburbs, and only one is elsewhere, Goochland County, a suburb of Richmond.

As Northern Virginia grew rich on industries of the future—information technology, national security, and the like—other parts of the state struggled to get an economic foothold in the 21st century. Tobacco, manufacturing, and textiles—longtime drivers of the Southern economy—stalled. Mills and auto-parts plants closed.

Before Mark Warner’s visit to Galax, one of the area’s biggest furniture companies shut down, laying off 275 people. Next door to Galax, Grayson County’s unemployment rate was above 7 percent, about twice Northern Virginia’s.

In these hard times, Richmond, Roanoke, and Southside look to the north and see a spoiled rich kid.

“Northern Virginia is a product of the massive amount of dollars coming out of the federal government,” says John Garner, chair of the Galax Democratic Party. “The folks in Northern Virginia give themselves more credit than they deserve.”

The economy to the south is nothing like it is in Northern Virginia, says Judy Brannock, director of Twin County Regional Chamber of Commerce, which serves Galax as well as Carroll and Grayson counties: “Everybody’s watching the economy go down here, and fuel prices are going up. So when Northern Virginia asks for more, we say, ‘Hey, we have less to begin with.’ ”

A few hours before the fiddlers convention, Mark Warner is scheduled for a tour of Main Street in the town of Wytheville, about 30 miles north of Galax. Warner steps out of a campaign car in a blue button-down, a tie, and slip-on loafers. He’s limping, thanks to a thigh bruise suffered in a pickup basketball game. “I made the mistake of trash-talking a 19-year-old kid,” he says.

A young woman approaches shyly. “I’m Mark,” he says, but she knows who he is. She’s brought her camera and asks him to pose with her for a photo.

Warner is a rising star in national politics. In the Senate-race polls, he’s whipping his GOP opponent, former governor Jim Gilmore. At the Democratic national convention in a few weeks after his Galax trip, he has the coveted slot as keynote speaker.

When Warner won the governor’s seat in 2001, Virginia tilted heavily Republican. Yet he left with high popularity ratings. If Virginia is to tip from red to blue in the presidential race, pundits say, he’ll show the way.

But Warner’s 2001 win was distinctive for another reason: Of the commonwealth’s 70 governors to date, he was only the third to hail from the Washington suburbs, following Chuck Robb (who won in 1981) and George Allen (1993).

Rural Virginia’s grip on political power is a legacy of Harry Byrd. Byrd was elected governor in 1925, when he was 38, and went on to the US Senate in 1933, becoming a champion of rural voters. His son Harry Jr. was a political broker in his own right and succeeded his father in the US Senate in 1965. Hundreds of family loyalists were installed in local government in Southside and the southwest.

As Northern Virginia grew and changed, it clashed with the Byrd machine. Perhaps the biggest battle followed the Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling outlawing school segregation. Byrd and his allies led the South’s “massive resistance” movement to defy the order. Governor Lindsay Almond, a Byrd lieutenant, warned of “those who would overthrow the customs, morals, and traditions of a way of life which has endured in honor and decency for centuries.”

In Arlington, where blacks pressed for integration, many newcomers to the state saw little honor in the old Virginia “way of life.” With activists in Norfolk and Charlottesville, they pressed for integration and in February 1959 won the day when four black students enrolled at the all-white Stratford Junior High School.

A few years later, Northern Virginia challenged the Byrd machine more directly. After the 1960 census recorded big population growth, Northern Virginia was due seven new delegates and two more state senators, according to Virginia Tech historian Peter Wallenstein’s Blue Laws and Black Codes. But Byrd’s allies in the legislature made few changes. Delegates for rural districts represented as few as 20,000 residents, while the two Fairfax County delegates each cast votes for 143,000 people.

Arlington delegates C. Harrison Mann and Kathryn Stone filed suit. They lost in Virginia’s highest court but won in the Supreme Court, which ordered redistricting in several states facing “one man, one vote” lawsuits. A new apportionment giving Northern Virginia more representation went into effect in 1966, and the legislature that year passed a state sales tax—anathema to Byrd and his allies.

Since then, each new census has given Northern Virginia more political clout. Chuck Robb after his 1981 election made a point of adding Northern Virginians to his Cabinet and key state posts. As candidates looked to the wealthy north to bankroll their campaigns, their platforms began to reflect upstate concerns. In the 1989 governor’s race, Doug Wilder, a Richmond native, proposed a university in Northern Virginia in addition to George Mason. His opponent, Marshall Coleman, ran ads describing Northern Virginia traffic as the commonwealth’s biggest problem.

A coalition of powerful business executives took up the Northern Virginia cause in Richmond, often on behalf of George Mason, which emerged after World War II as a branch of UVa and won its independence in 1972. Led by Til Hazel, the group lobbied for increased higher-education spending. Downstate lawmakers who wanted George Mason to be a small commuter school tried to block the addition of a law school to the university.

Even with its new influence, Northern Virginia was often thwarted by what’s known as the Dillon rule, named after John Dillon, an Iowa judge in the mid-1800s. Troubled by the municipal corruption of that era, Dillon argued that local leaders—particularly those in the cities—lacked the “intelligence, business experience, capacity, and moral character” to run government. In rulings and writings, Dillon advanced the idea that the powers of local governments are limited to those granted by the state.

The Dillon rule became part of Virginia law by the start of the 20th century, and the state remains one of the few to adhere rigorously to it. Famous for his fiscal conservatism, Harry Byrd embraced the Dillon rule and used it to block counties or cities from levying anything but a property tax.

Local officials cursed Dillon. It meant they had to go hat in hand to the General Assembly for even small initiatives. Over the years, the legislature has granted localities broader taxing authority. Fairfax and Arlington, for example, levy a tax on business, professional, and occupational licenses.

But locals still resent the Dillon straitjacket. They want money, but they also want to manage their growth and decide basic governance issues. Fairfax, whose million residents make it bigger than seven states, chafes the most. For nearly ten years, it’s lobbied Richmond for the right to ban guns in government buildings, including teen rec centers. It’s also asked to ban discrimination against gays in housing, employment, and other areas of life. Several Northern Virginia jurisdictions have petitioned for the authority to regulate commercial parking on residential streets. Each time, the answer has been no.

Issues like these, Northern Virginia officials say, don’t get a sympathetic ear from lawmakers who don’t know what it’s like to live in an urban area. “There are probably legislators in the General Assembly who’ve never been to Northern Virginia,” says one area official. “And there are some who’ve been here and never want to come back. It’s so foreign to what they’re used to.”

In Wytheville, Mark Warner has stopped at Skeeter’s, renowned for the hot dogs it serves in a century-old building. Customers sit at a soda-fountain-style counter. Warner orders a dog with mustard and coleslaw and heads toward a burly man with a beard at the end of the counter: “Hi, I’m Mark. . . .”

The owners of Skeeter’s, Bill and Farron Smith, grew up together in southwest Virginia and raised two kids there. They’ve backed Warner for years, in part because he’s brought businesses to the area. One of his biggest coups: a deal with Northrop Grumman to open a state information-technology operation in nearby Russell County, which translated to hundreds of well-paying jobs.

Such work could be outsourced to Asia. And Northrop Grumman could have set up in tech-friendly Northern Virginia. But the beauty of the Internet, Warner says, is that such work can be done anywhere. Why not rural America?

The Smiths like that kind of thinking. “He’s plain-talking, and what he says makes a lot of sense,” says Bill Smith. “He’s someone who gets things done.”

The Smiths give Warner high marks for cleaning up Virginia’s budget mess in 2004. Facing a deficit that threatened the state’s AAA bond rating, Warner pushed a $1.5-billion tax increase through a legislature that included many fiercely antitax Republicans. The key features: a 17.5-cent increase in the cigarette tax—a perennial on the Northern Virginia lawmakers’ wish list—and a half-penny increase in the sales tax.

One of Warner’s failures came on transportation, an issue that bedevils every Virginia governor. In 2002, he persuaded the legislature to allow Northern Virginia and the Hampton Roads area to vote on a half-cent sales-tax increase to pay for new roads and transit. In the DC suburbs, this would have yielded nearly $5 billion for new roads and mass transit over 20 years.

The referendum bombed in both regions. In Northern Virginia, it was attacked by antitax conservatives along with smart-growth activists who argued persuasively that more roads equaled more sprawl.

Voters also bristled at the idea that they would pay a special tax for what they saw as a state responsibility.

“We got whupped,” Warner says.

Richmond and Northern Virginia have sparred over roads for more than 40 years. When the state moved in the 1960s to build I-66 under President Eisenhower’s interstate-highway program, an Arlington citizens group sued, citing potential noise and pollution. A compromise was forged—the highway would run only four lanes in the county—but the years-long fight drove up construction costs and antagonized state officials. One told Til Hazel: “Never again will I send money or highway help to Northern Virginia. There are plenty of places in the state that want our money and our help.”

After Robb’s 1981 election, Northern Virginia’s delegation arrived in Richmond hell-bent on getting new funds for Metro and roads. “We’re bound and determined that, by God, our urban needs are going to be recognized,” Annandale delegate Vivian Watts told the assembly. Within a few years state money for Fairfax roads had doubled along with Metro funding.

House of Delegates speaker A.L. Philpott, a power broker from Southside, marveled at Northern Virginia’s clout. “That’s the third political party here,” he said.

In 1986, Northern Virginia helped punch through the largest spending package in 20 years, all dedicated to transportation. Bill Thomas, Til Hazel’s law partner, organized businesses behind the plan. Vivian Watts—whom Governor Gerald Baliles had tapped as secretary of Transportation—led a traveling road show that detailed the new blacktop planned for each legislative district.

The result? A half-penny sales-tax increase, a one-cent tax increase on car sales, a 2.5-cents-a-gallon increase in the gas tax, and $422 million a year in new roads and mass transit. Northern Virginia leveraged the cash for key projects such as the Fairfax County Parkway, I-95 HOV lanes from the Beltway to Triangle, and the Greenway from Dulles airport to Leesburg. The money also helped expand congested routes such as Braddock Road in Annandale and Routes 7, 28, and 123.

The victory was seen as a coming-out party for Northern Virginia in the legislature, but that was premature. The package won in part because Baliles smartly packed it with something for everybody, upstate and down.

Funding plans since have tried without success to re-create this magic. To much of the state, transportation is a problem for the rich people up north. In a 2006 Washington Post survey, only 9 percent of Southside residents rated transportation as an “extremely important” issue.

“Transportation is a priority for you folks in Northern Virginia,” says John Garner, the Democratic Party leader in Galax, “but it’s not a priority for anybody else.”

Since 1986, the legislature has passed nothing that rivals the Baliles plan. The gas tax remains at 17.5 cents a gallon, ninth-lowest in the country. It generates about $900 million—a figure that, factoring in inflation, equals the yield in the first year of the Baliles plan. Since then, Northern Virginia has added a million new people and even more cars. The number of miles people in the region drive is up 79 percent. Northern Virginia advocates say we’re years into a crisis that will hurt the region’s economy—and slow the revenues flowing to state coffers. By refusing to pay for new roads and transit, they say, Richmond is cutting its own throat.

Lawmakers have trotted out lots of revenue schemes to pay for more transportation. But debate turns ugly when it comes to the question of who pays: the state as a whole or Northern Virginia.

Last year the Virginia Senate—which Democrats have controlled since the 2007 elections and is fairly responsive to Northern Virginia needs—endorsed a plan by majority leader Dick Saslaw of Fairfax to raise the gas tax statewide by six cents. The Republican House backed a plan to allow Northern Virginia and Hampton Roads to tax themselves—a revised version of legislation passed in 2007 but ruled unconstitutional by the state Supreme Court because it created a taxing authority that wasn’t elected.

Governor Tim Kaine split the difference. He pushed new levies that included higher taxes on car sales, an increase in vehicle-registration fees, and a one-cent sales tax increase in Northern Virginia and Hampton Roads.

Debate spilled into a special session where lawmakers fought like toddlers in a sandbox. Neither side won, everybody lost a little dignity, and the split between Northern Virginia and the rest of the state seemed even bigger.

Judging by this battle, the differences between Northern Virginia and the rest of the state appear irreconcilable. Secession is the logical next step. Even Thomas Jefferson believed that “a little rebellion now and then is a good thing.”

But Northern Virginia faces a few obstacles before it can follow the lead of West Virginia. The US Constitution prohibits secession without the approval of the state that’s left behind—a provision skirted by West Virginia thanks to wartime exigencies. If Richmond won’t let Fairfax regulate parking, it’s not likely to let Northern Virginia walk away.

Creating a new state in Northern Virginia would end the meddling of downstate lawmakers, but that’s no guarantee of harmony. The Northern Virginia delegation is not known for unity. Even in the summer’s transportation battle, area lawmakers couldn’t agree to any single plan.

There’s little doubt that a Northern Virginia–only legislature would lean left. The delegation is packed with Democrats, many of them liberals who’ve been marginalized in Richmond. The first 100 days of the new state no doubt would see passage of gun-control laws and an increase in the cigarette tax, which at 30 cents a pack is the fourth-lowest in the country. There would also be moves to give local jurisdictions more autonomy.

But if freedom from Richmond led to tax increases, Northern Virginia might lose the competitive economic advantage it enjoys over DC and the Maryland suburbs. Businesses that locate in Northern Virginia often praise the low tax rate as well as the state’s laissez-faire regulatory style—both a function of Virginia’s conservative government. Forbes named Virginia “best state for business” three years in a row; Maryland is number 14 in this year’s ranking.

Even without secession, the next few years promise to change the north-south dynamic in Northern Virginia’s favor. In legislative redistricting after the 2010 census, the region is likely to pick up two or three seats in the House of Delegates and perhaps a Senate seat.

Because cities and suburbs are fueling the state’s population growth, urban issues will get a better hearing in the future—and as the state becomes more urban, it begins to look more like Northern Virginia. Companies focused on healthcare, technology, and finance are joining big tobacco as players in the Richmond economy. Even tiny, remote Galax has seen an influx of Hispanics.

Time, plus a little more understanding, will heal divisions in the state, says Mark Warner.

Warner’s in his campaign car as it pulls away from Skeeter’s and heads to another Main Street event. He’s been coming to southwestern Virginia since the late 1980s, when he ran Doug Wilder’s campaign for governor. To Northern Virginians who complain that those outside Washington don’t understand their transportation problems, he tells the story of a trip he took to the western corner of the state before he was governor. He was there to talk politics, but because he sat on a state transportation board, the locals wanted to show him their crumbling roads.

“I’ll always remember: The park ranger took me down Route 609 from Breaks to Grundy. It was the windiest, skinniest, most broken-down road. And the ranger said, ‘You think about on a cold winter morning when you’ve got a coal truck coming up this hill and a school bus going down.’ ”

Warner’s sympathetic to Northern Virginia charge that it gets shortchanged by the state—but only to a point. Much of the money sent to Richmond goes toward funding K–12 schools in the state’s poorest regions, where property taxes don’t bring in enough to pay for even a minimal education.

What’s more, estimates that Northern Virginia sends far more to Richmond than it gets back don’t take into account the matching money that the state provides toward federal highway projects, such as the new Wilson Bridge and the Springfield mixing bowl. Nor do they factor in the state’s subsidy of four-year colleges, which Northern Virginia kids attend in numbers greatly disproportionate to their share of the state’s population.

“Does it even out?” he says. “Probably not. But it’s not this totally out-of-whack balance that folks think it is.”

Northern Virginia’s never going to get a dollar-for-dollar return on its taxes. Nor should it, Warner argues.

“Years ago, Northern Virginia was nothing. Southside carried Virginia’s economy for hundreds of years. The money was coming in the opposite direction. The fact is, the rest of the state should step up for Southside or for Southwest during these hard times.

“If I’m accused of doing that, I’ll take that hit any day.”

Night has fallen at the fiddlers convention by the time the Warner campaign arrives. A TV crew from Roanoke, the nearest media market, is on hand. “He visits this area so much, he’s on TV more than I am,” the reporter jokes.

A crowd gathers. To some in Galax, Warner is a hero. “We’ve got his photos everywhere in the office,” says Bill Webb, who runs the state employment agency in Galax. “We consider him a champion. When he visits down here, he sits and listens to you. No matter who you are—whether you’re the richest person in the world or the poorest—he puts his hand on your shoulder and looks you straight in the eye, just like he was your best friend.”

It takes Warner 45 minutes to work his way the couple of hundred yards from his car to the stage. People stop him to talk, shake hands, and get a photograph. He shares a laugh with the vendor selling pork-loin sandwiches. He doesn’t fit in here—few from Northern Virginia would. But he’s no longer an outsider.

On stage, Galax mayor C.M. Mitchell stops the mandolin competition and introduces a “special guest.”

“I’m going to be a smart politician and not say much,” Warner tells the crowd. “Enjoy the music, enjoy Galax, and have a great party.”

He waves, and as he turns to leave the stage, the crowd lets loose with its loudest ovation of the night.

This article first appeared in the November 2008 issue of The Washingtonian. For more articles like it, click here.

→ All Northern Virginia Articles

→ Should the New State Include DC?

→ Will Northern Virginia Become the 51st State?

→ We Draw the Borders of the 51st State

→ New Dominion of the Imagination