Michael Steele’s first prediction as the new Republican chairman reflected his sunny side. In a buzzing downtown DC ballroom, as Steele’s upset victory in the party-leadership race was being announced, he leaned over to his sister, Monica. “We’re going to have some fun,” he whispered.

What came next was anything but.

The Republican National Committee had turned to Steele last winter out of desperation. The race for chairman had come down, on the sixth and final ballot, to a tough choice: Steele, an outsider, versus a South Carolina party hack whose membership in an all-white country club was already generating bad publicity.

Less than two weeks earlier, Barack Obama had been inaugurated as the nation’s first African-American President. Electing the first black Republican chairman had upside potential. It could help change the image of a party whose failure to attract minority votes was a big problem. Steele’s supporters in the room that day were convinced that his experience as a Fox News commentator was a guarantee he’d be an articulate spokesman.

But a string of verbal blunders quickly made Steele, and the party, an easy mark for ridicule. In May, a Time cover story asking if the Republicans were going extinct said “it can be comical to watch Republican National Committee gaffe machine Michael Steele riff on his hip-hop vision for the party.”

Steele’s challenge had been to take his talents as a TV pundit—where the trick is often to spout the first thought that comes to mind—and transfer them to his new job as party spokesman.

Slow to recognize his problem, Steele tried to talk his way out of it. He claimed that his early mistakes—which included a blowup with Rush Limbaugh that turned into a damaging debate about who really spoke for Republicans—were part of a deliberate plan. “There’s a rationale, there’s a logic behind it,” he said on CNN. “It’s all strategic.”

It didn’t help that Steele had called abortion “an individual choice” in a GQ interview. His words flew in the face of decades of party doctrine and forced him to clarify his own anti-abortion views as a devout Catholic who once studied for the priesthood.

Steele’s amateurish performance shocked many in the party. Questions were raised about whether he should step down. The old guard found a nit to pick in the $18,500 that Steele spent redecorating his office at national headquarters. (The old decor, he told GQ, was “way too male for me.”) Some party elders wanted controls placed on his access to the party purse.

Democrats embraced Steele as the Republican they loved to lambaste. Seated before a wall of TV monitors at Democratic headquarters, members of the rapid-response team eagerly tracked Steele’s frequent cable appearances. Any howler they missed was quickly spotted by an army of liberal bloggers and launched into cyberspace.

His first year as chairman, troubling as it’s been at times for Steele and his party, fits a pattern. The man whose climb to national prominence began in a rowhouse in DC’s Petworth neighborhood has lived a roller-coaster life. His story is a series of personal successes followed by defeats, both political and personal. But in the end, he has always wound up back on top.

As this election year got under way, Steele was riding high again—too high, in the view of his detractors.

There were gripes that Steele was putting his own interests above the party’s, with paid speaking gigs as well as a new book and book tour that took congressional leaders by surprise. Veteran insiders fretted about the “burn rate” of RNC spending and worried about a fundraising falloff.

And yet, with financial help from Steele’s operation in Washington, Republican candidates took the biggest prizes of 2009 away from the Democrats—the governorships of Virginia and New Jersey. Donations flooded in, with more than 370,000 new donors and $81 million in contributions, according to the party.

Today, every indicator points to significant gains for Republicans in the coming mid-term elections. Campaign handicappers give them a chance of regaining control of at least one house of Congress.

As the national chairman of the Grand Old Party might say, what’s up with that?

Looking back from the vantage point of his Capitol Hill office, under the gaze of a Frederick Douglass portrait, the 51-year-old Steele says it’s a mistake to think that progress, in life or a political career, always follows a steady, upward course.

“There are a lot of folks who are blessed with that,” he says. “Barack Obama is one. He got on the track—next thing you know, he’s President. The rest of us do it the old-fashioned way. Trial and error. You make mistakes. You learn from those mistakes.”

For Steele, the first big mistake came early. In a precursor to what would occur more than three decades later, he let himself get carried away with his success.

It was the fall of 1977, and Steele had just entered Johns Hopkins on a partial scholarship. He was fresh out of then-all-male Archbishop Carroll High, a parochial school in Northeast DC where he’d been student-council president. Steele put his gifts as a politician to the test in his new environment.

“I knew most of my classmates by the end of my first week of school,” Steele recalled to a group of inner-city high-school students in DC last May. “I just networked the heck out of that bad boy. I was grooving. I was having a ball!”

He was elected president of the Hopkins freshman class, then let his academics slide. “I partied my behind off,” he says. “I heard there were classes, and some people told me I really should go. But I was having a good time.”

The next June, a letter arrived at his home in DC, advising him that he’d been expelled. He went downstairs to tell his mother, a sharecropper’s daughter who worked a minimum-wage job at Sterling laundry to send him and his sister to college. Through a Catholic charity, she had adopted Steele, born at Andrews Air Force Base in 1958, as an infant. Her first husband, William Steele, died when Michael was four, and she remarried a few years later to Defense Department truck driver John Turner. But as Steele likes to say, it was his mother who ruled the household.

Maebell Turner was standing at the stove, stirring a pot of grits for her son’s breakfast as he told her he’d been kicked out of college. She never looked up. After silently handing her son his plate, she told him, “Well, baby, I don’t know what you’re going to do, but come September you’re going to be at Johns Hopkins University.” With that, Steele says, “she walked out of the kitchen.”

Steele has told the story often, with some variations, as a motivational tool for others and as an example of his perseverance. He says he badgered Hopkins dean Michael Hooker into giving him a second chance. Steele took makeup classes at George Washington University summer school, was readmitted to Hopkins that fall, and graduated in 1981 with a major in international relations.

Just out of college and searching for his place in the world, he followed a calling he had felt since childhood. He entered an Augustinian pre-novitiate program at Villanova in 1981. “I knew what I was giving up,” he told the Hopkins alumni magazine in 2005. “It wasn’t like I had no clue about life, like I didn’t have any idea what poverty, chastity, and obedience would mean in a world that was throwing wealth and sex in your face every day.”

He eventually gave up his white robe and put himself on a track to become a lawyer. “It came down to, ‘Am I called to serve the people of God as a priest or in a business suit,’ ” Steele told the Baltimore Sun in 2002. Reverend Francis J. Doyle—his spiritual director at the Augustinian novitiate house in Lawrence, Massachusetts—told the paper in 2006 that Steele “gave himself very sincerely to the whole process of discernment.” He left the program after a year and a half, the Sun reported.

Steele returned to Washington, got a law degree from Georgetown in 1991, and joined Cleary Gottlieb as an associate. He left the Washington firm after six years when it was evident he wouldn’t make partner. He worked briefly as in-house counsel for the shopping-center developer Mills Corp., then formed his own consulting firm, the Steele Group, but struggled to make money. In 2001, after missing mortgage payments on his Largo townhouse, he was threatened with foreclosure.

Money problems had become such a big part of his life that the following year, when he was offered the chance to become Robert Ehrlich’s running mate as Maryland lieutenant governor, Steele’s teenage son, Michael, had one question for his father, according to the Washington Post: How much does it pay? During the campaign, Democrats attacked the Republican Party for giving candidate Steele a $5,000-a-month consulting fee.

The setbacks he encountered in the private sector mirrored the arc of his climb through the Republican ranks. He moved to suburban Maryland in the mid-1980s while a law student and became a party activist. State Republican chairman Audrey Scott still remembers the eager volunteer who started at the bottom in Prince George’s County. “If you needed to wave signs, if you needed to stuff envelopes, he was never above it,” she says.

Steele tells another story about joining the GOP. Attending his first party dinner in 1988, he was disappointed to find himself shunned by almost everyone there.

“Now, it’s not like I didn’t stand out at this event,” he wryly said to the Hopkins magazine. “For one thing, I was the tallest person in the room.”

When he told his friends about it, they were incensed, Steele says. “They were like, ‘See, I told you these Republicans, they don’t give a damn. They just don’t like blacks.’ ”

He had been raised in a Democratic family, and college classmates have described him as liberal back then. Steele says Ronald Reagan inspired him to become a Republican. Reagan’s traditional social values were in sync with those taught by his mother, who rejected welfare because, Steele said she told him, “I didn’t want the government raising my children.” He views public service and his involvement as both “a passion” and “a calling.” Says Steele: “This is an extension of the vocation that I pursued in the monastery.”

His determination to push through the rejection from fellow Republicans strikes some as evidence of a determined work ethic and others as opportunism. University of Maryland political scientist Ron Walters, who has followed Steele’s career, points out that for an aspiring black politician, the Republican Party offers at least one advantage: “The line is shorter.”

By 1994, Steele had become chairman of the county central committee in Prince George’s, where Democratic voters outnumber Republicans by better than five to one. When he helped defeat a 1996 Democratic ballot initiative to repeal the county’s property-tax cap, senior Maryland Republicans took notice. They encouraged him to run for public office.

His first try—in 1998, for Maryland comptroller—was a bust. Despite the support of top party leaders, he finished third in the Republican primary. That fall, frustrated in a bid to become chairman of the state Republican Party (a job he got two years later), he considered running for Congress. News of his plan leaked when former boxing champ Mike Tyson—then married to Steele’s sister, Monica—blurted it out to reporters at the Rockville courthouse after pleading no contest to assault charges.

For someone whose entire career has played out in the local area, Steele long remained a stranger to the national political scene in Washington. That may help explain why he’s still viewed warily by many on K Street and in Congress.

Last summer, at a private meeting with Republican congressional leaders, Steele was dressed down over what Senate Conference chairman Lamar Alexander regarded as Steele’s invasion of their turf: making policy for the party. Former Maryland governor Robert Ehrlich—who served four terms in the House and keeps in close touch with former colleagues—says Hill Republicans are still trying to figure Steele out. “They didn’t know him,” Ehrlich says. “He just sort of came out of left field.”

As chairman, Steele has earned more than his share of criticism, but he’s made a name for himself—and built a following among rank-and-file voters around the country. The same probably can’t be said of his predecessor in the party post, a Kentucky banker named Mike Duncan, or even his more accomplished Democratic counterpart, former Virginia governor Tim Kaine.

The job that brought Steele to national attention had even less going for it than the one he holds now. It’s no accident that politicos refer to a lieutenant governor as “lite governor.” Some states don’t even have the position, and Maryland’s is among the weakest in the country. It’s left completely to the governor’s discretion, under the Maryland constitution, to decide what duties, if any, the lieutenant governor gets to perform.

Steele might still be back in the state-party trenches had it not been for Ehrlich’s decision to add his name to the Republican ticket in Maryland in 2002. The move almost didn’t happen.

Bob Ehrlich, a self-confessed control freak, shuddered at the prospect of having to worry at every moment during the campaign about what a ticket-mate might be saying. So he gave serious thought to running without one.

The weak Republican bench in Maryland left Ehrlich with few good choices. Eventually, he settled on Steele, an old friend he’d come to know through politics. “It wasn’t a long list,” Ehrlich says, “and we thought we were compatible and so it made sense.”

Ehrlich went on to defeat the heavily favored Democrat, Kathleen Kennedy Townsend, eldest of Robert F. Kennedy’s offspring. As always, the top of the ticket got most of the attention. But Steele—on his way to becoming the highest-ranking black elected official in state history—attracted attention, too. Not all of it was welcome. He got dinged when Democrats challenged his boast that his stepfather had served as RFK’s chauffeur. Steele was forced to acknowledge that he’d embellished the facts. His stepfather, who moonlighted as an airport cabbie, had driven Kennedy exactly once.

As lieutenant governor, Steele was a loyal number two. He headed an education task force that promoted charter schools and a commission designed to get minority-owned businesses more state contracts. He questioned the fairness of the way the state applied the death penalty, suggesting that there had been bias along economic and racial lines. But critics, many of them Democrats, said he had little to show for his efforts.

In 2006, at the urging of President George W. Bush and White House political adviser Karl Rove, Steele sought an open US Senate seat in Maryland, giving up an opportunity to run with Ehrlich for another term. The Senate race was a long shot, but it offered Steele a chance to win public office on his own.

An innovative series of campaign ads featuring the camera-friendly candidate and a cute little dog—produced by the media firm of his top political strategist, Curt Anderson—drew national acclaim. The contest was marred by Democratic overreaching, an illegal effort to plumb Steele’s personal finances. A Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee researcher who illegally used Steele’s Social Security number to obtain his credit report pleaded guilty to fraud, and a second staffer also resigned.

Like other Republican contenders across the country, Steele was battling strong headwinds. He tried to play down his Bush ties, criticizing the administration for its handling of the Iraq war and Hurricane Katrina. And he described the Republican “R” as a “scarlet letter” in Maryland. But he didn’t back away from his Catholic Church–inspired opposition to all forms of abortion and the death penalty.

On Election Day, he polled one-fourth of the black vote and a majority of the white vote statewide but still lost by 10 percentage points to Ben Cardin.

Passed over for the job of national party chairman when the Bush White House dictated the selection, Steele joined the Fox network’s stable of conservative commentators and became head of GOPAC, which works to elect Republican candidates on the state and local levels.

He also had more time to spend at his Upper Marlboro home. His wife of nearly 25 years, Andrea Derritt Steele, is a Hopkins classmate with a graduate business degree from Wharton who became a Riggs Bank vice president, a job she gave up to raise their two sons, Michael and Drew. They’re active in St. Mary’s Catholic Church in Landover Hills, and Andrea works with Catholic charities. Described as very private and shy, she seldom attends political events.

When Steele announced his candidacy for RNC chairman in late 2008, many wrote him off. He was the outsider on territory that favored candidates who ran from their seats on the national committee. Rove was among those who dismissed Steele’s chances, telling an associate that “it’s just not going to happen.”

However, the little secret about national-party leadership contests is that they’re much more like high-school politics than real elections. Steele hit the road to try to charm the 168 activists around the country who would make the decision. His main assets were the same ones that have served him well over the years: personal warmth, a crushing handshake, and the ability to listen empathetically.

When all was said and done, Steele won with 91 votes, six more than needed.

At a news conference minutes after his win in late January 2009, he couldn’t resist unleashing an audacious boast. Reminded that Obama, campaigning against Steele in 2006, had dismissed him as an amiable fellow with a thin résumé, he responded: “I would say to the new President congratulations. It is going to be an honor to spar with him. And I would follow that up with ‘How do you like me now?’ ”

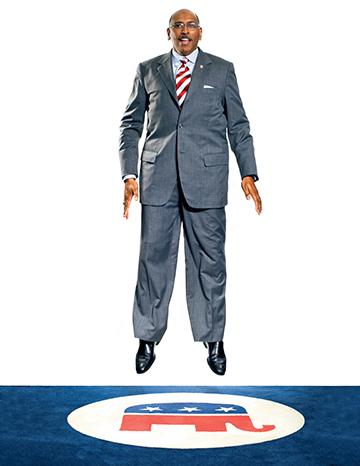

Asked what he planned to do to change the party’s image, Steele stepped from behind the podium. “I got a nice suit,” he replied. “And the tie is good.”

The six-foot-four clotheshorse says he likes to shop at Nordstrom and buy tailored attire from Kustom Looks in Silver Spring, a favorite of politicians from both parties. Kwab Asamoah, the proprietor, matches 39-inch sleeves to what Steele calls his “7½-foot wingspan.

But as it turned out, snappy duds weren’t enough to keep the new chairman from tripping over his shoelaces.

Steele acknowledges that at times he has a tendency to take things too far. “And I get checked on that, just as when I was a young boy and I pushed the envelope too far and my Mama was there to check me.”

But there’s an edge to his voice when he talks about a double standard that he believes has been applied by his critics, and he posits racism as the cause: “I don’t see stories about the internal operations of the DNC that I see about this operation. Why? Is it because Michael Steele is the chairman, or is it because a black man is chairman?”

Steele’s decision to build his career as a Republican in Prince George’s, the nation’s wealthiest majority-African-American county, has left more than a few scars. He has often heard the term “token black,” and when he chaired the Maryland Republican Party, the white Democratic head of the state Senate called him “the personification of an Uncle Tom.”

Steele still bears a grudge against the Baltimore Sun, which said in a 2002 editorial endorsing Kathleen Kennedy Townsend for governor that Ehrlich’s running mate “brings little to the team but the color of his skin.”

Bob Beckel—who ran Walter Mondale’s 1984 presidential campaign and got to know Steele in the green room at Fox—thinks Steele is “a lot shrewder than people think he is.” Beckel calls him physically intimidating but “also one of the sweetest individuals you’ll ever meet.” Says the Democrat: “He’s done the one thing you need to do in politics. He’s exceeded expectations.”

Steele’s critics, many of them Republicans, claim he’s pursuing a personal agenda at the party’s expense. They point out how he seems eager to put himself on equal footing with Obama. The morning after his election as party chairman, Steele said that the White House had been trying to get in touch with him, presumably so the President could congratulate him on his own path-breaking achievement. The call never came through.

In a 2009 interview with CNN’s Don Lemon, Steele made the case that all these years after Martin Luther King’s famous speech at the Lincoln Memorial, “you now have two African-American men sitting at the pinnacle of political power in this country—one running the country and the Democratic Party, the other running the Republican, the national Republican Party.”

Steele says Obama never accepted his invitation for a social get-together, extended in 2005 after the new senator from Chicago arrived in Washington. But he says “he and I had, I think, a very good moment” when Obama gave him a shout-out at last spring’s White House Correspondents’ Association dinner.

“Michael Steele is in the house tonight,” Obama said. “Or as he would say, ‘in the heezy,’ ” using urban slang for “house” to make good-natured fun of Steele’s attempts to give the Republicans a hipper image. “What’s up?” Obama asked to laughter as Steele stood in response, clearly tickled that the President had singled him out of the celebrity-studded crowd.

What is up with Steele?

If 2010 turns out to be a good Republican year, it would lift Steele’s stock. A second term as party chairman, which he appears to want, would carry him through the 2012 presidential election. After that, perhaps a Cabinet job, if Republicans unseat Obama, or maybe a lucrative private-sector position. Steele makes no secret of his desire to be Maryland’s first black governor. But that goal may be out of reach in one of the nation’s most Democratic states.

Some in Republican circles think he sees himself as a presidential contender. Steele says he’s focused only on raising money and winning elections. His new book, Right Now: A 12-Step Program for Defeating the Obama Agenda, just out from conservative Regnery Publishing, is fueling theories about loftier intentions, even if the sales won’t threaten Sarah Palin’s Going Rogue.

A White House try would be the ultimate roller-coaster trip. Steele won’t categorically rule it out. But he insists he doesn’t view himself as a candidate and adds, “I don’t plot that far out.”

Right now, “this is where God wants me,” says Steele. “I have no idea what the future holds.”