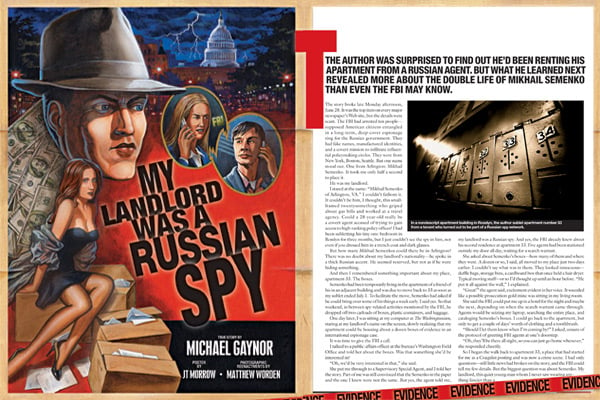

The story broke late Monday afternoon, June 28. It was the top item on every major newspaper’s Web site, but the details were scant. The FBI had arrested ten people—supposed American citizens entangled in a long-term, deep-cover espionage ring for the Russian government. They had fake names, manufactured identities, and a covert mission to infiltrate influential policymaking circles. They were from New York, Boston, Seattle. But one name stood out. One from Arlington: Mikhail Semenko. It took me only half a second to place it.

He was my landlord.

I stared at the name: “Mikhail Semenko of Arlington, VA.” I couldn’t fathom it. It couldn’t be him, I thought, this small-framed twentysomething who griped about gas bills and worked at a travel agency. Could a 28-year-old really be a covert agent accused of trying to gain access to high-ranking policy offices? I had been subletting his tiny one-bedroom in Rosslyn for three months, but I just couldn’t see the spy in him, not even if you dressed him in a trench coat and dark glasses.

But how many Mikhail Semenkos could there be in Arlington? There was no doubt about my landlord’s nationality—he spoke in a thick Russian accent. He seemed reserved, but not as if he were hiding something.

And then I remembered something important about my place, apartment 33. The boxes.

Semenko had been temporarily living in the apartment of a friend of his in an adjacent building and was due to move back to 33 as soon as my sublet ended July 1. To facilitate the move, Semenko had asked if he could bring over some of his things a week early. I said yes. So that weekend, in between spy-related activities monitored by the FBI, he dropped off two carloads of boxes, plastic containers, and luggage.

One day later, I was sitting at my computer at The Washingtonian, staring at my landlord’s name on the screen, slowly realizing that my apartment could be housing about a dozen boxes of evidence in an international espionage case.

It was time to give the FBI a call.

I talked to a public-affairs officer at the bureau’s Washington Field Office and told her about the boxes. Was that something she’d be interested in?

“Oh, we’d be very interested in that,” she said.

She put me through to a Supervisory Special Agent, and I told her the story. Part of me was still convinced that the Semenko in the paper and the one I knew were not the same. But yes, the agent told me, my landlord was a Russian spy. And yes, the FBI already knew about his second residence at apartment 33. Five agents had been stationed outside my door all day, waiting for a search warrant.

She asked about Semenko’s boxes—how many of them and where they were. A dozen or so, I said, all moved to my place just two days earlier. I couldn’t say what was in them. They looked innocuous—duffle bags, storage bins, a cardboard box that once held a hair dryer. Typical moving stuff—or so I’d thought up until an hour before. “He put it all against the wall,” I explained.

“Great!” the agent said, excitement evident in her voice. It sounded like a possible prosecution gold mine was sitting in my living room.

She said the FBI could put me up in a hotel for the night and maybe the next, depending on when the search warrant came through. Agents would be seizing my laptop, searching the entire place, and cataloging Semenko’s boxes. I could go back to the apartment, but only to get a couple of days’ worth of clothing and a toothbrush.

“Should I let them know when I’m coming by?” I asked, unsure of the protocol of greeting FBI agents at one’s doorstep.

“Oh, they’ll be there all night, so you can just go home whenever,” she responded cheerily.

So I began the walk back to apartment 33, a place that had started for me as a Craigslist posting and was now a crime scene. I had only questions—still little news had broken on the story, and the FBI could tell me few details. But the biggest question was about Semenko. My landlord, this quiet young man whom I never saw wearing anything fancier than a T-shirt and shorts, who made small talk about the weather and the World Cup.

Who was Mikhail Semenko, really?

He wasn’t like the others in the spy ring. They worked in pairs, husbands and wives bound by marital and foreign allegiances; he worked alone. Most used fake names; he didn’t.

They also held positions of some influence, such as Donald Heathfield of Boston, a “strategy expert” who had been marketing a software tool that predicted how future events could affect the fortunes of global corporations. Semenko worked at a small travel agency in Clarendon.

The others had lived in the United States for more than a decade, carefully cultivating their all-American lifestyles as their mission dictated, owning homes and blending into suburban life.

Semenko’s story starts in the fall of 2005, when he arrived in the States for the first time to attend Seton Hall University in New Jersey for work on his master’s degree in diplomacy and international relations as well as Asian studies. He had previously studied in Russia and China.

He graduated in 2008. Despite positions as an intern for the World Affairs Council in DC and as a staffer for the Conference Board in New York City, he found long-term employment only at Travel All Russia, selling customized tours to his native land.

The company specialized in dealing with a multilingual clientele, and Semenko’s talents weren’t wasted: He was fluent in Russian, English, Mandarin Chinese, and Spanish. When Travel All Russia relocated from New York to Arlington in the fall of 2009, so did he.

Mark Grueter arranged for the Arlington apartment. The two were acquaintances from Grueter’s time as a Peace Corps volunteer in the Russian Far East; from 2001 to 2002, he was the adviser of a Model United Nations Club at Amur State University in Blagoveschensk, Russia, where he met Semenko.

“He was very nice, polite, humble,” says Grueter. “And he didn’t participate in any political discussions, like some of the other students. He was pro-America.”

They kept in touch through e-mail over the next few years. When Grueter was looking for someone to sublet his apartment in Arlington, he says, Semenko was oddly insistent, even relentless, in securing a place close to DC: “He kept calling and calling and calling. He didn’t want to waste any time. I thought it was strange because he was always so polite to me.”

Before moving, however, Semenko returned to Russia, apparently to replace his student visa with a work visa. He returned there again in April 2010, just two months before the arrest, for reasons that remain unclear.

News reports describe Semenko as a suave and stylish man who, according to a neighbor, drove a Mercedes. But those close to him knew a different person. He was “awkward,” they say, “goofy.”

“He was clumsy,” one friend says. “You would ask him to fix a computer or something and he would break it.”

And he didn’t drive a Mercedes. He drove a beat-up 1992 Toyota Camry.

Semenko loved talking about government, especially one country’s in particular.

“China, China, China,” the friend says. “That’s all he wanted to talk about sometimes.” Semenko received a certificate in Chinese languages and culture and taught English in China for almost two years.

One of his responsibilities, according to his profile on LinkedIn, was introducing students to Western culture.

Separating the spy from his personality isn’t easy. Like many young professionals in DC, Semenko would talk at length of government policy and international relations. In theory, this might have been the perfect cover: a foreign agent, disguised as another smart, ambitious 28-year-old climbing the Washington ladder.

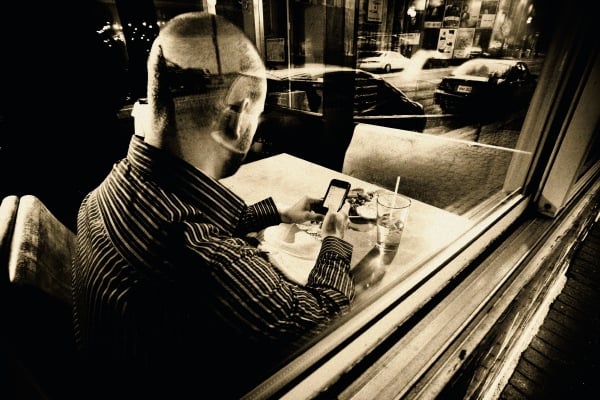

Authorities caught Mikhail Semenko in a popular Wisconsin Avenue restaurant secretly communicating with a Russian government official. Photograph by Matthew Worden

It’s not clear when the FBI uncovered Semenko’s trail or how he became a spy in the first place. But the circumstances of his arrest are well documented.

The federal complaint against Semenko and Anna Chapman, another member of the espionage ring, describes their long-term mission: “to become sufficiently ‘Americanized’ such that they can gather information about the United States for Russia, and can successfully recruit sources who are in, or are able to infiltrate, United States policy-making circles.”

According to a senior FBI official, investigators had used sophisticated surveillance equipment—and lots of it—to monitor the entire spy ring. The FBI knew who the spies were talking to and where they were going. Investigators tracked their daily lives using state-of-the-art cameras and recording devices. The G-men had quietly stalked their quarry for almost a decade, and officials marveled at the spies’ patience, their willingness to spend years assimilating into American culture.

The complaint cites two instances that incriminated Semenko as a member of this group. The first was on June 5, when agents observed him carrying a bag and entering a crowded restaurant on Wisconsin Avenue in Northwest DC alone. Ten minutes later, a car with a Russian diplomatic license plate entered the restaurant’s parking lot, circled the area, and parked. No one got out.

At the same time, FBI agents detected the presence of an encrypted wireless network in the vicinity. Using a simple, commercially available network detector, they found that it was the same type of covert channel the FBI had noticed in the Anna Chapman investigation. The equipment and tactics the two spies used to talk to their handlers seemed to match.

After about 20 minutes, the car drove away from the parking lot, and Semenko left the restaurant minutes later. The complaint surmises that Semenko and the Russian had been using the encrypted network to communicate with each other.

The FBI had more evidence of potential espionage. The complaint says that the Russian official in the car had previously been observed engaging in a “brush pass”—a secret hand-to-hand exchange—with another member of the spy ring six years earlier in Forest Hills, New York.

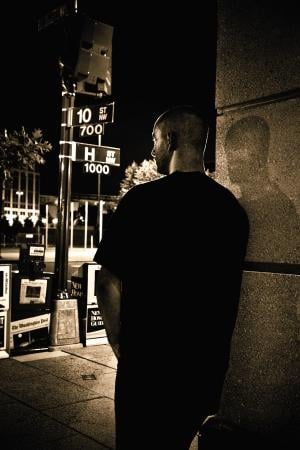

But after the events of June 26, the FBI had all it needed to arrest the spies. That night, an FBI agent posing as a Russian agent placed a call to Semenko, asking him to meet. They exchanged apparent code words, and Semenko agreed.

Just before sunset, the undercover agent met with Semenko near Tenth and H streets, Northwest. He asked if the June 5 communication at the restaurant had been completed. “I got mine,” Semenko said.

They moved to a nearby park bench and spoke for about 30 minutes. The undercover agent tried to make Semenko reveal certain facts that would show he was knowingly engaged in espionage. The government wanted that evidence for its indictment. The ploy worked. Semenko walked the FBI agent through the steps he’d taken to ensure that their communication was successful. He told him where he’d received his training. They also discussed how he’d hidden the equipment and what to do if it was recovered by authorities.

The undercover agent again brought up the June 5 meeting at the restaurant, asking Semenko if he had seen “our officer.”

“No,” Semenko said. “I am not supposed to look, though. I’m not supposed to be looking out.”

After the meeting, the agent handed Semenko a folded newspaper with $5,000 in cash concealed inside. He told Semenko to drop it off in a park in Arlington the next day between 11 and 11:30 am.

Semenko did exactly that; he was under surveillance the entire time. That same afternoon, he knocked on the door to my apartment and asked if he could finish moving the rest of his boxes in. Only hours after that, Sunday night around dinnertime, the FBI led him away in handcuffs.

Not 24 hours later, I was walking back to apartment 33, less than a half mile from Ray’s Hell-Burger, where President Obama and Russian president Dmitry Medvedev had talked diplomacy over lunch not a week earlier.

I was expecting a battalion of black SUVs with tinted windows and agents in suits and earpieces swarming the building. But nothing seemed amiss when I arrived. People were outside, kids playing on the sidewalk.

There wasn’t any sign until I went upstairs. Five agents lined the narrow stairwell, satchels resting at their feet, dressed in plainclothes with badges clipped to their belts.

“So I guess you’re the FBI,” I said.

The man in front nodded with a smile: “And you must be our lucky guy.”

I unlocked the door and led them in, then pointed out the boxes, careful to show them what was mine. I didn’t want the FBI confusing my stuff with a spy’s, lest I become a suspect.

Because Semenko could have had access to the apartment while I wasn’t there, the agents would have to inspect the entire place, including my belongings—everything I owned, they said, down to the DVDs on the shelf.

Before the agents let me leave, they watched as I filled a backpack with clothes for the night. They watched the drawers as I pulled out T-shirts, and they stood in the bathroom doorway while I dropped a toothbrush and some dental floss into a dopp kit. Then they picked over the backpack itself, unzipping pockets, checking folders. Some loose sheets of paper were at the bottom, including a beat-up copy of a speech I gave when I ran for vice president of my 11th-grade class.

The agent’s eyes ran over each document carefully, as if searching for some type of code or hidden message. When he finished, he carefully folded the pages and put them back in place.

“Did you win the election?” he asked.

I stayed at a friend’s apartment. So much talk of spies and Cold War–style espionage had given me the vague, paranoid feeling that I was being followed. The FBI had been following Semenko for as long as I’d been in the apartment—there was a good chance the phone and the apartment itself had been bugged, maybe even had been under video surveillance.

My friend and I decided it was appropriate to watch a spy movie. We chose The Manchurian Candidate, the Frank Sinatra version.

By delivering a bag containing $5,000 in cash to a drop site in an Arlington park, the spy fell into an elaborate trap set by the FBI. Photograph by Matthew Worden

Reporters across the country were just beginning to sort out the details of the Russian spy network. And in Washington, more of Mikhail Semenko’s connections were about to reveal themselves.

On May 27, 2010, Steve Clemons, a senior fellow at the New America Foundation, struck up an interesting conversation with a stranger.

Clemons had just chaired his think tank’s meeting on the debate about American and Chinese approaches to capitalism. After the event, a young man approached him, introducing himself as a specialist in the Chinese economy.

They spoke for a few minutes on the issues. The young man told him he maintained a blog on the Chinese economy and wrote long articles about China’s labor unions, currency manipulation, and cooperation with Russia. Clemons was impressed, he says—enough to suggest they meet for lunch before his next trip to China.

They exchanged business cards. The stranger’s name was Mikhail Semenko. Clemons put his contact information in his laptop.

Clemons was shocked when the news broke a month later. They’d never followed up on lunch, but his opinions of the young man weren’t changed. He recalls Semenko as an “obviously smart” person who carried himself like the best of DC networkers.

“I meet hundreds of people a week,” says Clemons, “but I don’t usually put all of them in my laptop. I didn’t look at him as a fly-by-night person. I thought he had content and depth.”

Clemons says he didn’t sense any ulterior motive lurking behind their interaction, just a genuine interest in the issues.

However, for people trying to find a foothold in Washington, Clemons is an important person to get to know. The New America Foundation is an influential policy institute, and Clemons, who directs its American Strategy Program, hosts frequent discussions with high-level officials. He often alerts friends and colleagues about an event that’s likely to sell out. He’s a prolific blogger with connections inside the Obama administration. Clemons could have been just the conduit into Washington’s policy elite that Semenko wanted.

“The kind of things I do exist in huge networks of people,” Clemons says, “and I meet a lot of people who want to be part of that.”

Semenko attended many events like this—big and small, casual and black-tie—and had been making his way around Washington circles.

“He would go to anything to do with diplomacy or think tanks or consultants, anything to jump-start his career,” a friend of Semenko’s says. “He would go to these things just to get to know people.”

Clemons describes Semenko’s approach to networking as casual and smart. He drew people to him rather than putting himself in the middle of a conversation. He stood out not for his charisma or forcefulness but for his easy ability to talk about the issues.

Semenko’s friend says my former landlord was desperately trying to find a way out of his job at the travel agency. He would job hunt for hours, submitting résumés, e-mailing think tanks and policy institutes. It has been reported that Semenko applied to the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace as well as Clemons’s New America Foundation.

The FBI’s investigation of the spy ring had already lasted the better part of a decade, so it’s not hard to imagine that these agents could have been left to their own devices for another few years. Semenko was still looking for a foothold in Washington when the FBI swooped in on June 26, a date one senior FBI official says had been set well in advance. But considering the impressions Semenko was making around town, to what heights could he have risen with just a bit more time?

On Tuesday afternoon, two days after the arrests, I was in apartment 33 watching the FBI agents begin their search.

The June heat wave had just begun, and the place was sweltering. The agents wiped sweat from their foreheads as they hovered over the pile of Semenko’s boxes and plastic bins. They explained that they needed a separate warrant for the boxes, because the one they had covered only my possessions. That meant I’d need another day’s worth of clothing.

One of them got on the phone with the US Attorney’s office. Piece by piece, he went through the pile, describing each of Semenko’s boxes in detail—the size, the color, any markings. A few pieces of luggage had locks on them. I asked an agent how the FBI would get inside. By knifing through the fabric?

“No,” she said, laughing. “We have our ways.”

She explained the methods of the FBI search. Any mishandling of potential evidence and the case was lost. These boxes would have to be accounted for every step of the way to the courtroom to avoid the risk of tampering. A cautious, slow process of combing the entire apartment would be necessary. Unlike on TV cop shows, no couches would be torn up, no beds flipped over. One of the agents told me they prided themselves on being careful.

Two more agents came into the apartment, struggling with a massive black case as the heat of the room hit them. They were members of the FBI’s Computer Analysis and Response Team, and I watched them remove tiny screwdrivers and tangles of wire from the case. They began to disassemble my laptop, hooking the guts up to a large hardware scanner and copying my hard drive to examine later.

Meanwhile, one of the agents was looking inquisitively at a hallway door. He had noticed it the previous afternoon, a padlocked door that I always assumed concealed a water-heater closet. But now it looked suspicious.

He examined the thick lock and shined a flashlight through the door’s vents. “We’re gonna need a warrant for this, too,” he said.

By the end of the search, which continued the next day, ten agents had crammed into the small, steamy apartment, looking for anything from a stray document to a cache of clandestine communications equipment.

The questions I have about my former landlord linger. He seemed separate from the other spies—at first it appeared he might have been a simple “money man” charged with laundering cash around town, perhaps to Michael Zottoli and Patricia Mills, two other spies arrested in Arlington. But his biography—the language skills, the networking, the ambition—points to larger things.

John Slattery, a former FBI counterintelligence official and currently an executive with BAE Systems Intelligence and Security, says a case of this magnitude has many legs, many connections left to explore: “If a guy plays his cards right and becomes a real professional, an academic, or even just a consultant, he can touch a lot of people.”

Semenko’s approach seemed to be working.

“He didn’t stand out for me because he was some sort of dashing, charismatic person,” says Steve Clemons. “He was just interesting.”

Almost as soon as the drama began, it ended. In the span of 11 days, the accused spies all pleaded guilty to the charges against them. Then the Americans and the Russians cut a deal. Mikhail Semenko and his nine compatriots boarded a government-chartered airplane that whisked them off to Vienna, Austria. On the tarmac, they switched planes with four Russians who’d been in prison after allegedly spying for the United States. (One still swears he’s innocent.) Semenko and the others flew to Moscow. They’ll probably never return to America, but the mystery remains. Why were they here? What did they find?

< p>Says Slattery: “This case is far from over.”

After the FBI finished the search of apartment 33, two agents came to my office to give back the key and have me sign some final documents.

“Just out of curiosity,” I said, “did you find anything in those boxes?”

They paused and said they couldn’t go into detail. “But yes,” one said, “we had to seize a few things.”

When I returned to the apartment that night, everything was back in its place, as if no one had been there at all. Even my DVDs were in the same order.

Later, I sought out a close friend of Semenko’s to try to make sense of the story and find the answers I was looking for. But the friend had been taken up in the whirlwind just as quickly and knew only as much as the news had reported. It was clear the experience had taken its toll.

“I haven’t been eating,” the friend said, head pointed downward and shaking. “And I still don’t understand the whole story. I just can’t believe this would ever happen.”

Neither can I.

This article first appeared in the September 2010 issue of The Washingtonian.