When you die, if you’ve lived a good life, people will grieve. Your family and friends will meet in a church or a synagogue or a funeral home to pay their respects. At some point, an announcement will appear in a local paper. The news of your passing will spread. Eulogies may pop up on the Internet from long-forgotten friends. Your death, in other words, won’t be a solitary event.

When Jennifer Lynne Matthews—a mother of three from Fredericksburg, Virginia—died, there was no such public mourning. For the outside world, the tributes were very brief. Her family members were unwilling to share their memories. No obituary was written. And yet her death was noted by some of the nation’s most powerful officials—including the President—and her life was saluted with a star on a memorial wall.

Matthews was a daughter, a mother, a wife. And last December, she was one of seven Central Intelligence Agency employees killed in Khost, Afghanistan, by a man who blew himself up after being welcomed onto an American military base.

Matthews died doing work she believed in. She died trying to find the people who’d attacked her country on September 11, 2001. But—in tribute to the silent spirit with which she worked and as consequence of the botched operation in which she lost her life—the CIA, the Obama administration, and Matthews’s family would prefer that’s all you ever know about her.

Matthews, who was 45 when she died in the most devastating attack on the Agency since the war on terror began in September 2001, was the CIA chief at Forward Operating Base Chapman, a station near the mountainous Afghanistan/Pakistan border. She was, according to officials, also one of the United States’ more experienced al-Qaeda analysts.

The suicide bomber was a Jordanian physician who had promised Matthews and her team detailed intelligence about al-Qaeda. He claimed he had access to its most senior leaders, that he’d even met them in person. What he was offering was so tantalizingly specific that Matthews might have believed he’d lead her straight to the men she’d been hunting for more than a decade: Osama bin Laden and his top deputy, Ayman al-Zawahiri. As it turned out, the bomber was probably working for these same terrorists; the Pakistani Taliban later claimed credit for the attack.

Matthews’s death—she and her Khost colleagues are arguably the highest-profile US casualties of the war on terror since onetime NFL star Pat Tillman was killed in Afghanistan in 2004—wasn’t a private affair. However, her life still is mostly secret.

The Washington area is home to thousands of people like Jennifer Lynne Matthews, who live one life with their families and in their communities and a different one at work. Thousands of local residents work for the 17 US intelligence agencies, assorted Pentagon entities, and government contractors that call Washington home.

In Fredericksburg, Matthews’s family lives on a rural road without sidewalks, near streets with names such as Poplar, Stony Hill, and Countryside. Nearby houses are modest but on large plots of rolling land. Some fly American flags. Others have small boats parked outside. Matthews’s home is gray, with dark shutters and a front porch. One recent workday, a minivan sat in the driveway near a mailbox for the local paper, the Free Lance–Star.

From the outside, nothing would indicate a secret life—no video cameras or fences—but that anonymity is how the nation’s spies blend in. In our region, they’re all around.

You might see them in the local supermarket or at a PTA meeting, and you might think you know them. But even in an increasingly interconnected world, you’ll likely never find them on Facebook or Twitter. These friends and neighbors have, like Matthews, dedicated themselves to a national mission—protecting America. And a double life is part of that bargain.

Ask the CIA or Matthews’s colleagues or just about anyone who knew her to recall the details of her life—not the secret parts, just the simplest facts—and they offer mostly platitudes.

Scores of Washingtonian inquiries were met with closed doors and no comment, abruptly concluded telephone calls, and unanswered letters or e-mails. Months after an initial request for information about Matthews and the lessons the CIA learned from Khost, the Agency’s director, Leon Panetta, declined an interview. So did Valerie Plame Wilson, the hardly press-shy former spy whose cover was blown during the Bush administration and who had worked with Matthews in the Agency. “Wishing you well with this important story,” she said via e-mail while promoting Fair Game, the Hollywood movie that tells her story.

From interviews with those willing to disclose what they know and public records, the early life that emerges resembles most American childhoods.

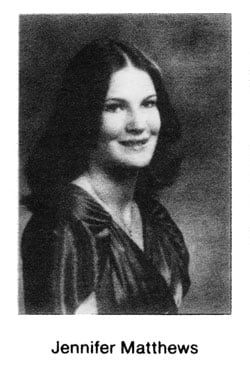

Jennifer Lynne Matthews was born in Penbrook, Pennsylvania, in 1964. She was a middle child. Her mother was a nurse, her father a commercial printer. She graduated from Central Dauphin East High School in Harrisburg in 1982. She was a member of the National Honor Society and Youth for Christ. She looks out from page 45 of her senior-class yearbook. In an era when Farrah Fawcett’s sassy feathered hair was the rage, Matthews’s brown locks are styled simply, parted in the middle with a flip at the bottom. She wears a blouse, a necklace, and a smile. Her classmates voted her “most likely to be the next Barbara Walters.”

Matthews joined the CIA in 1989 and seemed a good fit. “She was self-assured, and she could blend into the environment,” says a Capitol Hill staffer who met Matthews overseas.

Details about her early career have never before been made public.

Matthews spent her first seven years at the Agency as an analyst, among those workers who absorb intelligence submitted by others in the field and then assess what the CIA has learned from it. By the mid-1990s, she moved to the CIA’s counterterrorist center, tracking al-Qaeda in a then-quieter corner of the Agency that would see its importance spike after the Twin Towers fell.

Post-9/11, with more than a decade of experience under her belt, Matthews managed operations to find the top leaders in al-Qaeda. Once they were captured, she was in charge of looking at interrogation reports and vetting the accuracy of what the captives said. She also was responsible for providing questions for interrogators and debriefers. A US official with knowledge of the circumstances surrounding Matthews’s assignment says, “Jennifer was one of the US government’s top experts on al-Qaeda and other terrorist groups. She was capable, smart, and passionate about the mission.”

Her job at CIA headquarters in Langley often took her into the field, where she traveled to Asia and the Middle East, but never for more than a month or two.

There were high-profile assignments. She managed the operation that located Abu Zubaydah and led to his capture. Zubaydah was the first high-value al-Qaeda target captured after 9/11, and sources say Matthews was personally involved in his questioning. He was captured in 2002, shuttled around the world, and eventually held at a CIA black site—a secret prison—in Thailand, where he was waterboarded, beaten, and subjected to extreme temperatures and underwent other “enhanced interrogation” methods. Matthews was “integrally involved in all of the CIA’s rendition operations,” according to an intelligence source.

From 2005 to 2009, she served as chief of the counterterrorism branch in London, a flagship post that would mark her first extensive service overseas; her husband and children moved with her to the United Kingdom. One highlight of Matthews’s tenure was her role in the bust of the 2006 al-Qaeda plot to bomb as many as ten US-bound jets.

Matthews surely knew the risks she was taking by deploying to Khost, the remote reaches of a war zone, in September 2009. She volunteered for the assignment—though it would be her first long stint in such a dangerous place. She thought she was ready. Matthews’s pseudonym within the Agency was Ruth. Her nickname? “Ruthless.”

For Matthews, the move to Khost provided a chance to show she had the intelligence chops to help the nation make strides in the war on terror. Infiltrating al-Qaeda would have helped her earn her stripes and rise in the CIA.

“What impressed me about Jennifer was her competence and her commitment to what she was doing,” says Fran Townsend, who was the homeland-security and counterterrorism adviser to President George W. Bush and the only former high-ranking official who had met Matthews and would talk on the record. “You don’t go where she was and you don’t do what she was doing unless you really believe in it.”

Matthews was also part of a significant corps of women in the ranks of America’s spies. According to the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, women represent 38 percent of the intelligence-community workforce, which includes the CIA and 16 other agencies. In the six largest of them, 27 percent of senior executive positions are held by women. It’s hard to make a historic comparison about the rise of women in the intelligence world because such data has been kept only since 2005. But women have held key positions at the Agency, particularly in counterterrorism sections.

Congressman Silvestre Reyes, a Texas Democrat and chairman of the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, says Matthews was “a total professional.” She’d briefed him overseas on al-Qaeda earlier in 2009. “I don’t think there’s any reason to second-guess any of the things that she did there,” Reyes says. “There’s nothing that I know of in this that says that she was not prepared for that challenge. Quite the opposite, from my perspective.”

The facts surrounding Matthews’s death, and the CIA’s own review of the bombing, suggest otherwise.

The death of an officer has always been a private matter for the CIA. In Matthews’s case, there seems to be more than the usual number of reasons for discussing it as little as possible. Her early training as an analyst, some say, suited her for a desk job in Langley. But it’s not clear that it prepared her to identify the mistakes that ended up killing her.

In the CIA, there are analysts and there are field operatives. Their trades overlap, but their cultures have historically been distinct.

Robert Baer, an ex–CIA case officer who served in the Middle East, says assigning an analyst to the base-chief job is like putting a hospital administrator in charge of surgery. “We all bite off things we shouldn’t,” Baer says. “Matthews shouldn’t have been there. She didn’t speak the language. She didn’t know the country.”

Other former officers echo this view quietly, over dinner or cocktails, but won’t be quoted.

Forward Operating Base Chapman—named for Sergeant First Class Nathan Chapman, the first US soldier killed in combat in Afghanistan—sits on a dusty scrub of land near the mountains that divide Afghanistan and Pakistan. FOB Chapman has been a critical staging area for the CIA’s war on al-Qaeda and the Taliban. It’s a hub for intelligence gathering, a place where operatives collect leads on militants in two unstable nations and mount missions to kill their leaders, often using remote-piloted drones.

Its residents don’t take strolls around the compound to catch a breeze or enjoy the sunshine, and they wouldn’t wander outside the multiple security perimeters. It’s not the kind of place where a working mother could live with her school-age children. It’s the kind of place where everyone walks around in Kevlar vests.

“It has that sense of a scene out of Gunsmoke,” Townsend says. “You can’t think of this like a military post in the traditional sense.”

Matthews and her team determined that the Jordanian informant, Humam Khalil Abu Mulal al-Balawi, a physician by training, was poised to provide details that could help US officials infiltrate al-Qaeda. Al-Balawi claimed to have met with al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri, Osama bin Laden’s number two. The CIA had been working for years to develop this kind of inside intelligence. His revelations could have helped turn the tide of a war against an amorphous enemy that has shown a relentless appetite for American death and destruction.

“You had visions of sugarplums and promotions dancing in everybody’s heads,” says Fred Burton, former deputy chief of the counterterrorism division of the State Department’s Diplomatic Security Service. “If I pull this off,” Burton says Matthews and her colleagues must have surmised, “my career can be made.”

The CIA officers at Khost were far from home. Perhaps that’s why they relied so heavily on the CIA’s allies in the region, and one in particular, to help them vet potential new spies. Much of that work was done by the Jordanian General Intelligence Department (GID). Those who know how relationships work in the interwoven global intelligence community say there’s perhaps no closer bond than that between the CIA and the GID. And al-Balawi had the GID’s seal of approval.

“You have a very special relationship with certain countries: the Brits, the Aussies, the Canadians, the Jordanians, the Israelis,” Burton says. “And if they’re going to vouch that this asset they’re bringing to you is good, you’re going to take that for granted.”

In Bob Woodward’s new book, Obama’s Wars, the author describes a December 2008 briefing that Michael Hayden, then the CIA chief, gave President Obama, in which Hayden cavalierly suggested that there are foreign intelligence operations that ultimately serve as de facto US entities. Woodward writes: “Hayden said the CIA pumped tens of millions of dollars into a number of foreign intelligence services, such as the Jordanian General Intelligence Department, which he said the CIA also ‘owned.’ ”

Matthews and her team leaned heavily on the GID in determining al-Balawi’s abilities to provide intelligence about al-Qaeda. He had been a radical who blogged on a jihadist site. The Jordanians took him in, and with extensive coaxing they turned him. Or so they thought.

“The Jordanians had been under intense American pressure to infiltrate al-Qaeda, and Balawi was the best they could do,” says Robert Baer, who wrote about the Khost bombing for GQ magazine in April.

The Americans wanted to meet al-Balawi, but the logistics were a challenge. They couldn’t go to him, to the often impassable regions lorded over by the Taliban. So the CIA decided to bring al-Balawi to them and to use the Jordanians to facilitate the meeting. In a sign of the high expectations for it, the White House was briefed in advance, according to Baer.

Burton says the meeting was the culmination of “a perfect storm of catastrophes.” The first failure point was deference to the Jordanians. If the US government and the CIA wanted to host the al-Balawi meeting, they should have managed the circumstances with more authority, Burton says.

The second failure was in not screening al-Balawi when he entered FOB Chapman. In a war zone, trust should never be assumed—not even, Burton adds, when a close friend and ally with the best of intentions gives the go-ahead: “There should have been some sort of physical search by somebody of this informant”—a pat-down or a pass through a metal detector.

A third mistake, as evidenced by the outcome of the day, was to have so many people greet al-Balawi. Who decided that it was a fine idea to welcome a onetime radical jihadist with a full band of American spies and contractors? And, as some reports indicated, with a birthday cake.

If al-Balawi was who he said he was and his intentions were pure, no one wanted to risk alienating him by giving him a physical once-over. But Baer says the failure to be more skeptical was inexcusable—and a sign of a CIA team in Khost without proper field training. “It was complete sacrilege,” he says.

Some are more forgiving. They describe the Khost disaster as an example of the human cost of doing business in the world’s most treacherous locations, where friend and foe can become blurred. Matthews, they suggest, would never have been alone in determining how the face-to-face with al-Balawi went down. Langley surely would have weighed in. And sources say al-Balawi was being groomed by the GID as early as January 2009—months before Matthews was dispatched to Khost.

“You do the vetting, but you send that back to headquarters to ask whether or not you should pitch this person and take them on as a regular source,” says Mark Lowenthal, a former assistant director at the CIA who also served as staff director of the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence. “The decision is not being made entirely in the field. The whole burden doesn’t fall on them.”

CIA director Panetta, sources say, was fully apprised of the December meeting with al-Balawi at FOB Chapman and was waiting with interest for an update about its outcome.

“To some degree, we let down our guard a bit,” says Ted Gup, an investigative reporter and author of The Book of Honor: The Secret Lives and Deaths of CIA Operatives. “That is the business of spying on both sides of the line. What the Agency does is dupe others; in this instance, we were duped. It’s an age-old game—with failed consequences here.”

Defne Bayrak, widow of the bomber, praised her husband’s bravery during a January interview with CNN and called him a martyr. The CNN reporter told Bayrak, a mother of two, that he thought she might express sympathy for the loss of another mother, Jennifer Lynne Matthews.

“For what purpose is CIA in the Afghan territories?” Bayrak said when prodded in that direction. “Why did they invade our lands? I believe she shouldn’t have gone there. It’s her fault.”

The families of the CIA dead are less outspoken. Though they’re free to talk about their loved ones, most have chosen not to.

Lois Matthews, Jennifer’s mother, declined to be interviewed. She says the family wants to stay unified in a decision about media interviews and that Matthews’s husband, Gary Anderson, prefers that she and others not comment. In a soft voice, she calls her daughter “a remarkable person” and “a special girl.” Anderson did not respond to a request for comment.

In a way, by staying silent, the families are honoring Matthews’s wish.

Says Gup: “If you have a loved one who is in the Agency and they are killed in the line of service, you do not want to do something to discredit or stain their sacrifice. So if your loved one believed in secrecy and believed in the mission of the Agency, you’re not likely to do something to compromise the values for which that person lived and died.”

Discretion as a death pact.

The Khost fallen include two women and five men. Five were CIA employees; two were contractors. In addition to Matthews, they are Elizabeth Hanson, Darren J. LaBonte, Scott Michael Roberson, Dane Clark Paresi, Jeremy Jason Wise, and Harold E. Brown.

“[Matthews] and all those lost or wounded that day deployed to protect the lives and liberties of their countrymen,” Secretary of Defense Robert Gates said in a speech to former intelligence officials in May. “They represent the very best that our nation has to offer.”

They are memorialized with stars carved into a wall at CIA headquarters. And their names are inscribed in the Book of Honor, which rests under glass nearby and pays tribute to the 102 CIA employees who have died in the line of duty. But the Khost victims will hold a special place in modern CIA history.

“[Khost] will mark this generation the same way Beirut marked mine,” former CIA officer Ron Marks said in the Wall Street Journal, referring to the 1983 terrorist bombing of the US Embassy in Lebanon. Sixty-three people died in that attack, including 17 Americans and most of the CIA’s employees in the country.

For years, the Agency presented the surviving relatives of a person killed in the line of duty with a letter from the director expressing condolences. The family members would read it promptly and be required to surrender it to CIA officials, who would place it in a classified personnel file, an effort to avoid exposing the link between the fallen and the Agency.

To commemorate the seven killed last December, the Agency set up an internal database so staff could send condolence letters to the families. Officials compiled those in bound blue leather books. They were stamped with the Agency’s seal and presented in mahogany boxes with glass covers.

Panetta met at least twice with the families of all seven—first when the bodies arrived at Dover Air Force Base on January 4, then privately before the February 5 memorial ceremony in front of the CIA’s headquarters building. He has also met with some families to discuss the CIA’s investigation of the bombing.

The February tribute, attended by 1,300, was broadcast to every member of the Agency around the globe but was closed to reporters. Seven stars decorated the backdrop of a tent in which President Obama and Panetta spoke. Colleagues of the seven officers eulogized the deceased, too. There was music—“Danny Boy,” “America the Beautiful.”

Washingtonians might remember that winter day as the first of two storms that covered the city in a blanket of white and halted most activity for a week. One woman who attended the memorial recalls, “By the end of the night, the city was completely silent. We had a week to sit and think about this.”

The CIA paid for the families’ travel and lodging for the February memorial as well as a June ceremony when the seven stars were added to the wall. All seven who were killed in Khost, the contractors included, were awarded the CIA’s Exceptional Service Medal, an honor bestowed “for injury or death resulting from service in an area of hazard.”

Intelligence officer Harold E. Brown was one of the seven killed. His mother, Barbara Brown, recalls: “The agency he worked for—whatever it was—everyone that we’ve met in conjunction with it, has been more than helpful, more than caring, more than friendly. They are also hurt by his passing at a personal level. That goes from the bottom to the top. I have nothing but respect for all the people that work where he worked. I wish them all God’s grace.”

For Brown, Matthews, and each of the dead, there were mundane details after the bombing, such as life-insurance policies to be paid out to the families in a lump sum. And workers’ compensation is paid out monthly. The amount varies per officer based on salary grade—Matthews’s was GS-15, the most advanced category of government service.

Matthews probably wouldn’t have much liked the ceremony and sentimentality surrounding her death, Fran Townsend says. She was “not an emotive type.”

Putting the Khost failures in the past could be hard for the Agency. In October, Panetta released a summary of the Agency’s internal “after action” report on the Khost bombing. While it didn’t blame any individual or group, the three-page document revealed misjudgments on the part of Matthews and her colleagues, both at the base and in Washington.

The CIA’s review showed that the Khost informer turned bomber “was not fully vetted and that sufficient security precautions were not taken.” The report’s findings were reaffirmed by an independent review conducted by intelligence heavyweights Charles Allen, a four-decade veteran of the Agency who served from 2007 to 2009 as undersecretary for intelligence and analysis for the Department of Homeland Security, and Thomas Pickering, former US ambassador to the UN.

The CIA’s “missteps,” as Panetta called them in a letter to Agency staff, occurred as a result of “shortcomings” across a range of operations, from communications to management oversight to documentation. Panetta wrote that “the intense determination to accomplish the mission . . . influenced the judgments that were made.”

Read between the lines of that statement and it’s easy to sense concern within the Agency about its need for more and better-prepared agents on the front lines—particularly in positions such as the one held by Matthews. Among 23 recommended changes, the director announced the establishment of a War Zone Board of senior officers to review the organization’s staffing, training, security, and resources in dangerous areas. Counterintelligence officers, who are trained to recognize double agents, will help scrutinize future potential informants. And, Panetta said, the CIA will assemble a “cadre of veteran officers who will lend their expertise to our most critical counterterrorism operations.”

Many of these remedies point to flaws in Matthews’s work and that of her team. “While we cannot eliminate all of the risks involved in fighting a war,” Panetta wrote, “we can and will do a better job of protecting our officers.”

While the CIA can’t take revenge on al-Balawi in the hereafter, it can hunt down the men who sent him to Khost. FOB Chapman has been a hub for the CIA’s drone program. Since the bombing a year ago, the number of drone strikes has risen steadily. In 2010, President Obama more than doubled the number of such attacks from 2009, a year that already had seen more attacks than in George W. Bush’s eight-year presidency.

But the situation on the ground remains volatile. FOB Chapman was almost breached again in August 2010 when attackers wearing US military uniforms and suicide vests stormed the base and another nearby camp. Reports indicate that US forces killed 21 insurgents. As in Khost, the raid was sponsored by the Pakistani Taliban, which has close ties to al-Qaeda. The CIA has pledged not to retreat from Khost—or the region.

A few weeks after that second attack, Panetta flew to Khost to dedicate a plaque that honored the dead. It quotes Isaiah 6:8: “And I heard the voice of the Lord, saying, Whom shall I send, and who will go for us? Then said I, Here am I; send me.”

Matthews was laid to rest in Arlington National Cemetery. She is home again, in Virginia. A year later, her death is fixed, like that of so many others who share this resting place, as a moment in history. A Purple Heart recipient is buried to her right, and a veteran of three wars—World War II, Korea, Vietnam—to her left. The white marble stone reveals only the barest essentials of the woman beneath it:

JENNIFER MATTHEWS

CIVILIAN

DEC 6 1964

DEC 30 2009

AFGHANISTAN

This article first appeared in the January 2011 issue of The Washingtonian.