Finn Camper is an even-tempered appraiser of summer camps. The ten-year-old from Chevy Chase has been to music camp (“fine”), sports camp (“pretty good”), and baseball camp (“I hated that”). His favorite is run by the Audubon Naturalist Society at Woodend Nature Sanctuary, a 44-acre preserve five minutes from his home, where kids explore the outdoors in programs with names like “Where the Wild Things Roam” and “Magical Potions and Slimy Notions.” In Finn’s favorite program, “Starry Safari,” he learned about night creatures such as the vampire bat. Finn’s camp friends call him the Happy Camper, a reference to his last name.

Some kids today have a lot of demands on their time. With math homework, soccer matches, trumpet practice, and online games all competing for their attention, they don’t spend much time outdoors—and a growing body of literature shows they suffer physical and psychological consequences as a result.

At nature camps like Audubon, parents get a chance to pull kids away from computer screens and into the forest. Counselors and staff work to mix an ecological curriculum with traditional camp fare—group games, corny skits, wacky songs.

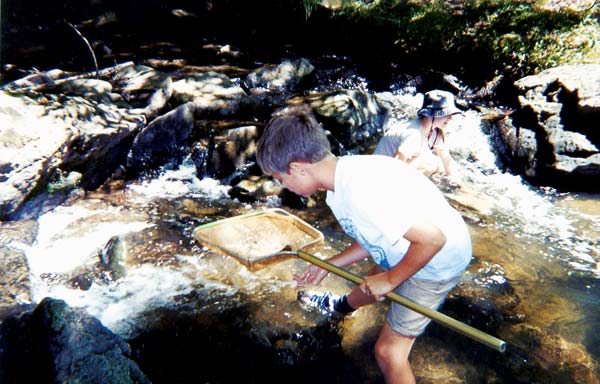

These nature camps differ in approach, but they all aim to impress children with the grandeur and wonder of the wilderness. At Congressional Camp, a 71-year-old Falls Church day camp, kids learn about conservation and mingle with the turtles at Tripps Run Creek.

The mission of Discovery Creek’s summer camps is “to turn young minds into stewards of the earth,” director Anne Zuk says. Based in Glen Echo on the banks of Minnehaha Creek, Discovery Creek blends free play with structured activities such as scavenger hunts in the woods and lessons in which kids build anemometers to measure wind speed.

Zuk teaches Little Explorers—the four-to-six-year-olds—about metamorphosis. At first they bungle the word’s pronunciation. “It takes about a week,” Zuk says. “By Friday, they go home and they’ve got it.”

To reach the pond at Woodend, children walk down a wood-chip path through tulip trees and honeysuckle. It’s a picturesque tableau, but not all the campers see it that way. “The kids are concerned about tigers and anacondas—and they’re serious,” says camp director Karen Vernon. “They learn a lot about animals in school and from TV, but not from the real outdoors.”

The benefits of a relationship with nature are distinct from those of physical exercise, says Julie Dieguez, coordinator of the Maryland No Child Left Inside Coalition, a nonprofit environmental-education coalition. She emphasizes the importance of a tactile knowledge of nature and believes that a hike through woods enriches children differently than a soccer game “on a nicely mowed and fertilized field.” Says Dieguez: “Seeing wildlife, smelling wet earth, hearing a forest filled with birds, catching a crayfish—those firsthand experiences hit home and have a memorable impact that ignites curiosity and a sense of exploration and discovery.”

In his book Last Child in the Woods, author Richard Louv introduced the phenomenon of nature-deficit disorder, which he defined as “the human costs of alienation from nature, among them: diminished use of the senses, attention difficulties, and higher rates of physical and emotional illnesses.” A 2003 Cornell University study, for example, found that children living in “high-nature conditions” coped better with life’s stresses than children who lived in homes isolated from nature.

At Woodend, Finn has seen monarch caterpillars feast on milkweed growing wild in the meadows. He has seen praying-mantis egg sacs the size of your thumb. He says he once watched as a flying squirrel miscalculated its flight path and sailed into a teacher’s hair. The only thing Finn hasn’t seen is a computer. Laptops, cell phones, game consoles—all are banned at Audubon. Finn doesn’t miss electronics at camp. “Who needs all that?” he says, though at home he likes to play online games.

Vernon says campers at Audubon often don’t want to go outside when it’s raining. But she tells them they won’t melt, that water doesn’t hurt, that there are bullfrogs and red-backed salamanders to be found. “Then they have a really good time,” she says. “They run around and splash in puddles and do the things I remember doing when I was a kid.”

Sara Melmed, 17, has spent the last three summers working as a counselor at Calleva, a camp with the tagline “Because adventure is not in the guidebooks and beauty is not on the maps.” Calleva is like Audubon injected with adrenaline: A fleet of about 25 buses whisks kids every morning from the Riley’s Lock base near Poolesville to locations across Maryland, Virginia, and Pennsylvania for rock climbing, whitewater canoeing, horseback riding, and other adventures in which the only rule is to keep moving. On the bus ride home, Melmed says, kids sleep soundly.

Calleva has a nature curriculum—it keeps river-ecology and “growing green” instructors on staff—but the underlying philosophy is that children soak up the outdoors best when they’re moving through it. “Kids like to learn new things and to achieve, to learn they can accomplish something,” says Julie Clendenin, Calleva’s outreach director.

Melmed’s mother, Lisa, has sent all three of her kids to the camp. “Calleva keeps them so busy doing active engagement,” she says, “that there’s no time to think, ‘Ooh, I’d better text somebody.’ ”

Melmed’s Calleva stories are about conquering fear. There was the time she walked barefoot on a trail of hot coals, and then there was a seven-year-old girl named Isabel, who refused to make a “wet exit” from a kayak. Isabel cried and skulked to the far side of the dock. Melmed consoled her, then demonstrated, spilling herself gently from kayak to lake. As Isabel watched, her face softened from terror to indifference. Melmed asked, “What’s the worst thing that can happen?”

With no ready answer, Isabel stepped into the kayak, held her nose, and rolled. When she emerged, Melmed says, she looked surprised. She wanted to do it again.

Next >> Nature Camps in Washington

NATURE CAMPS IN WASHINGTON

Adventure Links

Based in Clifton, this weeklong day and overnight program takes 8-to-14-year-olds canoeing, spelunking, rock climbing, and whitewater rafting in Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia. Contact the camp for rates.

800-877-0954

Audubon Naturalist Society

Campers ages 4 to 17 come to the 44-acre preserves in Chevy Chase and Leesburg. Day camps run $148 to $360 a week for Audubon members, $218 to $430 for nonmembers. Overnight programs are $288 to $600 for members, $358 to $670 for nonmembers.

301-652-9188

Barrie Camp

Barrie’s 45-acre Silver Spring campus has riding stables, fields, ponds, and streams. Two weeks of day camp cost $870.

301-576-2800

Browne Summer Camp

This camp’s grounds feature a competition-size swimming pool and three playgrounds. In the “Nature in Your Own Backyard” program, campers raise monarch butterflies from eggs. Open to children in preschool through eighth grade. The cost is $255 to $525 a week.

703-960-3000

Burgundy Summer Day Camp

This Alexandria day camp’s 25 acres include a pond, barn, and amphitheater. A week’s tuition for 4-to-15-year-olds is $340. Extended days are available for a surcharge.

703-960-3431

Calleva Outdoor Adventures

This family-owned camp on the Potomac River offers day and overnight programs. Core staff work full-time and lead campers (ages 6 to 15) as they rock-climb, kayak, and ride horses. A week of day camp costs $475 to $495; overnight is $795 to $1,200.

301-216-1248

Camp McLean

Three-to-ten-year-olds spend an hour a day with a science-and-nature specialist who leads nature walks and outdoor science experiments. Two weeks at this day camp cost $250 to $490.

703-448-8336

Camp Sonshine Wilderness Adventure

Rising fourth-through-tenth-graders hike, swim, build fires, and learn archery at this day camp near Silver Spring. Rates run $207 to $329 a week.

301-989-2267

Congressional Camp

This 40-acre Falls Church day camp has nature-themed specialty programs including “Green Science” and “Eco Quest.” Designed for children ages 3 to 14. One week costs $200 to $350.

703-533-9711

Discovery Creek and Discovery Adventure

Five day-camp programs are tailored to children ages 4 to 14. Days start at 9 am at multiple locations including Kenilworth Aquatic Gardens and Glen Echo Park. A week costs $295 and up.

202-488-0627 ext. 236

Grace Episcopal Day School

Led by an elementary-school science teacher, the four-day nature program for day campers ages six to ten has a bug-digging, creek-stomping, muck-making ecological curriculum. The four-day camp costs $290.

301-949-5860 ext. 54

Summer Safari Day Camps

At the National Zoo, campers learn about animal behavior through science projects, arts and crafts, and zoo walks. Four- and five-day sessions cost $280 to $350 for full day, $200 to $250 for mornings only. Kindergarten through seventh grade.

202-633-3026

Valley Mill Camp

This Darnestown day camp on a two-acre lake offers canoeing, kayaking, rock climbing, swimming, nature study, and more. Ages 4 to 14. Tuition is $2,940 for a six-week session, $1,470 for three weeks.

301-948-0220

YMCA Camp Letts

Set on a Chesapeake Bay inlet, this camp is more than 100 years old. Kids can canoe, swim, ride ponies, and build campfires. One- and two-week overnight programs for campers ages 6 to 16. YMCA members pay $300 to $1,315, nonmembers $330 to $1,365.

410-919-1410

This article first appeared in the February 2011 issue of The Washingtonian.