After being away from Washington most of the fall with other commitments, National Symphony Orchestra music director Christoph Eschenbach has been back at the podium the past two weeks. After kicking off this season’s celebration of the music of Beethoven last week—an event far outdone by the revelatory all-Beethoven concert given by John Eliot Gardiner and the Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique the same weekend—Eschenbach led the sort of program last night that has distinguished his tenure at the Kennedy Center. It combined youthful works by two titans of the 20th century, Benjamin Britten and Dmitri Shostakovich, a comparison that cast into relief the failure of a rather flimsy new work by American composer Osvaldo Golijov.

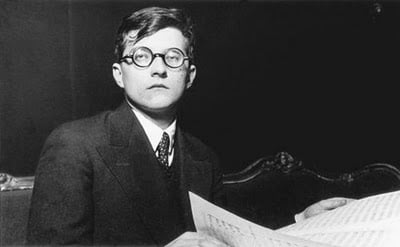

The NSO has not played Shostakovich’s first symphony since 1993, when Mstislav Rostropovich programmed it. It’s astounding that a student composer—Shostakovich began the symphony when he was 18 years old—could have penned such a fully formed work, with such freshness and variety of melody, harmony, and orchestral texture. Listening to it, one is struck by how precocious Shostakovich’s compositional voice was, and also how different music history might have been had the cultural open-mindedness that was enjoyed in Russia at this point, in the first several years after the 1917 revolution, endured. Of course, without the opposition of Stalin’s controlling cultural apparatus, Shostakovich might not have written the bitter, biting, grotesque music we love him for, but this first symphony seems to indicate that he would have done great things in any case.

As pointed out in the excellent program note by Thomas May, Shostakovich supported himself in these years by providing live musical accompaniment for silent films, and the sentimental and madcap scenes of that era’s movies informed his musical style. Eschenbach brought out an extraordinary range of colors and textures in this performance, with a jovial first movement edged with trickster mischief, followed by a madcap scherzo in the second movement. Although his teacher’s negative response to these movements reportedly tempted the composer to subtitle the work “a grotesque symphony,” the quotient of sarcasm is nowhere near that of the works he composed after the rise of Stalin. Plangent solos from oboe, violin, and cello gave a romantic sweep to the gloomy slow movement, tinged with motifs associated with funeral marches. The dramatic fourth movement contrasted exuberant fast sections with what seemed like tender closeups, even a death scene with a stark timpani solo, all reflecting again the influence of early cinema.

Britten’s violin concerto, Op. 15, has been heard much more often from the NSO, as recently as 2005, and this performance with Midori as soloist was mixed. It’s a magnificent piece of music, completed when the composer was in his mid-twenties, and Midori was at her best creating delicate watercolor washes of sound, the tone as fragile as a strand of saffron, like the main theme of the first movement, highlighted by timpani strikes and cymbal shivers and a jaunty little bassoon counter-melody. Eschenbach, on his toes, kept the NSO in line with his soloist, crafting their dynamic fluctuations to allow Midori’s violin to speak. The flautando and high harmonics were beautifully ethereal, but there were too many infelicities of intonation and raspy, crunchy technical issues in faster passages to consider this a top-notch performance.

As for the new piece by Golijov, one continues to wonder why this composer receives so many commissions—this is at least the third of his works played by the NSO in the past year and a half—especially when he’s notoriously bad about meeting deadlines. The evocative title, Sidereus, is borrowed from Galileo, but there’s little of astronomical significance in this repetitive, unremarkable overture beyond the title. The work was commissioned by a consortium of orchestras, who will all perform it—the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra had its turn just this past June—in honor of Henry Fogel, an important champion of orchestras who was executive director of the NSO in the 1980s. As has become the disappointing trend in Golijov’s most recent works, the piece does not have much to say, but it does so with a recognizable style: some jazzy woodwind riffs, some chintzy syncopations, and a lot of repetition. It would probably work quite well as a series of cues for various starry effects in a film. Eschenbach and the NSO are to be commended for programming new music—even when it’s bad, it’s rewarding to hear—but please, lay off the Golijov.

This concert will be repeated tonight and tomorrow night, December 2 and 3, in the Kennedy Center Concert Hall. Tickets ($20 to $85) are available through the venue’s Web site.