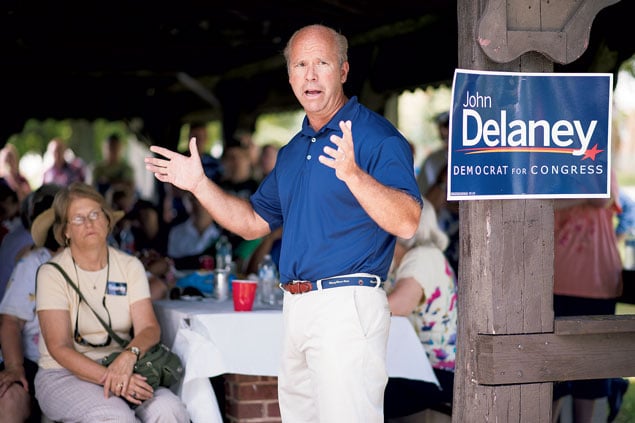

UPDATE 11/07/12: Yesterday John Delaney defeated Republican incumbent Roscoe Bartlett. Here’s our October 2012 profile of him.

John Delaney wasn’t supposed to be the Democratic nominee in

Maryland’s 6th Congressional District.

That role was intended for Rob Garagiola, the 40-year-old

state-senate majority leader from Germantown, a tall, handsome progressive

whom party leaders in Annapolis had given the green light last

fall.

Unlike Garagiola, Delaney hasn’t paid his dues in lower office.

His career in finance has progressives leery, and his message of

invigorating the private sector in Maryland to create jobs has others

fearful he’s a closet Republican.

If Delaney wins the seat, he’ll be one of the wealthiest

members of Congress—probably in the top five, with somewhere around $200

million in assets made from two financial companies he founded and built

in Chevy Chase.

Garagiola’s supporters painted him as a rich, out-of-touch

“1-percenter.” And with income averaging $14.5 million over the last seven

years, he’s not just in the top 1 percent—he’s in the top 0.1

percent.

But after a nasty, expensive primary campaign that party

leaders tried to squelch, Delaney is now given a strong chance of helping

those same Maryland Democrats pick up another House seat.

The race wasn’t in the immediate plans of the wealthy Potomac

entrepreneur until a gerrymandered redistricting proposal stirred him into

action last fall, and it certainly wasn’t in the plans of the Democratic

establishment that had redrawn the district lines with someone else in

mind.

Yet Delaney’s run for office came as no surprise to some of his

closest friends, including David Bradley, head of the Atlantic Media

group, who says Delaney has been “playing with this question for at least

a dozen years.”

He has “the striving gene,” says Bradley. “He’s been on a

vertical run through life.”

Hungry to capture another US House seat in Maryland, Democratic

leaders had put a target on the back of Roscoe Bartlett, the 86-year-old

Republican incumbent. They handed the bow and arrow to

Garagiola.

Leaders had first looked at how to reclaim the 1st

Congressional District on the Eastern Shore, but that proved too

difficult. Instead they dumped hundreds of thousands of new Montgomery

County constituents into the 6th and lopped off large swaths of

conservative voters who reliably supported Bartlett.

“I had never heard of John Delaney,” Garagiola says. But other

Democrats had, in particular those who had benefited from substantial

contributions from Delaney and his wife, April. In recent years, the

couple had given at least $183,000 to the national party and candidates

and $83,000 to the state party and candidates, some of whom were now

backing Garagiola, including Maryland governor Martin O’Malley and

lieutenant governor Anthony Brown.

The Garagiola forces were quick to attack Delaney’s business

record. They defined him not as the job-creating innovator he portrayed

himself to be but as an unscrupulous banker who preyed on others, financed

substandard nursing homes, and foreclosed on mortgages. Delaney, who went

to Columbia University on a scholarship from the electricians’ union his

father belonged to, was even portrayed as anti-union.

“What the establishment was trying to do was to position me as

a Republican running in the Democratic primary,” says Delaney, who does

have Republican friends and contributors and has given to a few Republican

candidates, such as Congressman Andy Harris. “I believe in the free

market. I believe that business creates the jobs in this country and not

government.”

Spouting such heresy, Delaney attacked Garagiola as a

Washington lobbyist and incumbent legislator far too cozy with Annapolis

special interests. Garagiola hurt himself by failing to disclose some of

his past lobbying income.

Garagiola garnered dozens of endorsements. But four weeks

before the April 3 primary, Delaney laid down two cards that trumped them

all: He was endorsed by President Bill Clinton, followed a few days later

by the Washington Post.

Delaney and his wife had been bundlers for Hillary Clinton’s

presidential campaign, and he had been a Clinton delegate to the

convention that nominated Barack Obama.

“The party of President Clinton is the party that I identify

with,” Delaney says. “Suddenly my message had credibility. I was a

Democratic candidate speaking to voters in language that they had

forgotten about.”

The Post endorsement stressed Delaney’s theme of job

creation and lambasted Garagiola’s connections to special

interests.

At the same time, Delaney was shoveling his own money into the

campaign, eventually $1.6 million in loans, most of it at the beginning of

March as he began dominating TV and radio.

Garagiola was no slouch at fundraising, bringing in more than

$700,000. But Delaney spent more than three times that.

In the end, the two candidates, with three other rivals, spent

$4 million-plus competing for just 38,000 votes cast. Delaney got 54

percent of the vote, trouncing the three-term state senator by spending

$135 a vote. Garagiola received 29 percent, spending $66 a

vote.

Comptroller Peter Franchot, the only statewide elected Democrat

to endorse Delaney, said the party establishment “got a real punch in the

nose.” Franchot, a persistent pain to party bigwigs on fiscal issues, said

it was Delaney’s emphasis on job growth that drew his support.

“Tammany Hall was all behind Garagiola,” Franchot says. In an

off-season spring primary, “the Democratic machine generally

prevails.”

But not this time.

If Delaney wins, it will be the latest in a string of successes

that had him taking two financial-services start-ups public by the time he

was 40. At 32, he was the youngest CEO of a company listed on the New York

Stock Exchange.

Delaney grew up in Wood-Ridge, New Jersey, not far from

Meadowlands Sports Complex, attending public schools and then Bergen

Catholic High. His father, Jack, was a union electrician and his mother,

Elaine, a homemaker. John worked construction in the summers.

Neither parent had gone beyond high school, but “my mother

wanted me to be a doctor,” Delaney says. So he went off to Columbia with

scholarships from the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, the

American Legion, and the Veterans of Foreign Wars. After working briefly

at St. Luke’s Hospital in New York, he decided medicine wasn’t for

him.

“I basically applied to law school as a way of telling my

parents that I wasn’t going to medical school,” Delaney says.

That’s how he wound up at Georgetown Law, where he met both his

future business partners and his wife-to-be.

He was hired at Shea & Gould in New York, where he had

interned. But just as he was about to move, he got engaged to April

McClain, a year behind him at Georgetown. She’d grown up on an Idaho

potato farm about half the size of the Bethesda Zip code. She didn’t want

to live in New York, and John didn’t want to head west, so they made their

life in DC.

After a brief time practicing at what was then Shaw Pittman,

Delaney and two friends from Georgetown Law, Ethan Leder and Ed Norberg

Jr., put lawyering aside and in 1990 bought a small health-care firm

called American Home Therapies.

Learning as they went, they managed to build the company and

then sell it three years later. “It gave us insight into the field that we

were going to finance,” Leder says.

The men then set up HealthCare Financial Partners, specializing

in the financing of small health-care firms. Delaney realized that with

changes in federal law, big banks were going to concentrate on consumer

lending and investment banking. This created a niche for lending to small

firms, especially those health-care companies whose assets were largely in

receivables owed to them by insurance companies and government

agencies.

They took the firm public in 1996, then sold it to Heller

Financial in 1999 for $500 million. In 2000, by this time with three young

daughters, the Delaneys moved from the District to a $4.5-million home off

River Road in Potomac and John started the company he still chairs,

CapitalSource. That company, too, was aimed at lending to small and

midsize businesses that big banks had abandoned, and it went public in

2003. Since the 2008 purchase of a California bank with 22 branches, much

of the company’s business is now as a federally regulated

bank.

Delaney also became part of the region’s nonprofit world, which

is always on the lookout for leaders who can provide both guidance and

financial support. Today he’s on the boards of Georgetown University, the

National Symphony Orchestra, and the Potomac School and is past chair of

St. Patrick’s Episcopal Day School, which his children

attended.

Few images show the couple’s connections quite as graphically

as the photo that ran on the Catholic Charities website this spring

promoting its annual gala, a black-tie event John and April cochaired for

two years. The photo shows the Delaneys smiling with Cardinal Donald Wuerl

and Supreme Court chief justice John Roberts and his wife,

Jane.

“John and Jane are very good friends of ours,” says April

Delaney, who like Jane Roberts, another Georgetown Law alum, worked as an

attorney on satellite communications. Their daughters were in a baby group

together, and the families are members of Little Flower Parish in

Bethesda.

“We actually have a lot of Republican friends,” says April.

“It’s a good thing to be bipartisan sometimes in this town.”

John Delaney has a comfortable life, wealth, connections, and

institutional leadership in the nation’s capital. Yet he’s angling to

become a freshman member of an exceedingly dysfunctional body that

requires reapplying for the job every two years.

“The stakes are really high” in the country right now, Delaney

says. He thinks he can help break the gridlock and political instability

that he believes is holding back economic growth. “I would feel really bad

about myself if I didn’t give it a shot.”

Last year, he started a nonprofit called Blueprint Maryland to

create a dialogue about job growth. It represented a deeper dive into

Maryland policy than he had taken before. The political contributions,

fundraising, and civic engagement had been going on for years, but “we

never thought we would jump in right now,” says his wife, who seems to

have embraced the candidacy as a joint venture. “Maybe five or ten years

from now.”

The congressional redistricting spurred them to action, even

though their home is two-tenths of a mile outside the 6th District. At one

point, April Delaney says, she told her husband: “If you don’t run for

this seat, maybe I will.”

John Delaney favors the approach of President Obama’s

Bowles-Simpson budget commission on fiscal responsibility: “We can’t

really have a debate about whether we can be fiscally responsible any

longer.”

He says raising capital-gains taxes, closing loopholes,

reducing defense, and lessening the future burden of Social Security and

Medicare, as prescribed in Bowles-Simpson, will help create a political

stability that “would be more powerful than any stimulus the government

could provide.”

But before Delaney can tackle those huge sticking points, he

has to overcome an obstacle more difficult than grabbing a slice of market

share from the big banks. He must beat ten-term incumbent Roscoe

Bartlett.

Many in his own party thought Bartlett should retire

gracefully. He was confronting a gerrymandered district with a large

contingent of Montgomery County Democrats he had never represented and a

presumably strong opponent in Garagiola. It would probably be the toughest

fight he had faced since winning the seat in 1992. Bartlett was already 66

years old when he won that race, and at 86 he’s now the second-oldest

member of the House.

Born dirt-poor in Kentucky, Bartlett had a career as a

scientist, teacher, and researcher, with 20 mostly government-owned

patents on lifesaving breathing equipment. Bartlett has always been an

unconventional Republican and has long backed energy solutions that reduce

dependence on fossil fuels. As an entrepreneur in his own right, he ran a

research consulting business that branched into construction and built 100

homes, many with solar power.

The father of ten with his wife, Ellen, Bartlett is modestly

wealthy as Congress members go, with as much as $8 million in assets, and

lives on a farm along the Monocacy River near Frederick.

Though allied with the Tea Party, Bartlett practices a quirky

brand of politics. At a June ceremony in Cumberland, part of the

economically depressed western end of the 6th District, he gave a brief

talk about the science behind the cool shade his audience was enjoying

under an old tree, then described the awesome display of 23,110 luminary

candles at Antietam National Battlefield that will mark this year’s

bicentennial of the bloodiest single day in American history. Then he

turned to the $1 billion in debt the US amasses every six

hours.

“It’s easy to get depressed and despondent when we think of our

polarization,” Bartlett said. “Shame on us if we can’t face the challenges

facing us.”

He gave mixed signals last year about his commitment to running

for reelection and got a slow start on fundraising, which partially led

two legislators to challenge him in the Republican primary. A majority of

the western Maryland Republican legislators supported state senator David

Brinkley against Bartlett, but the incumbent easily won the primary with

44 percent of the vote against seven opponents.

“There’s a history of underestimating Roscoe Bartlett,” says

Maryland GOP chairman Alex Mooney, a former state senator who briefly

considered running for the seat himself when Bartlett’s plans seemed

unclear. Mooney now works for Bartlett’s congressional office

part-time.

Bartlett must clearly win the older parts of the district that

know him well and, as one consultant put it, “stay in the ball game” in

Montgomery County, where neither candidate is well known.

Delaney’s advantages are clear. Unlike Bartlett or Garagiola,

he has no voting record to defend, and he can play to the anti-incumbent

feeling in both parties. Delaney’s emphasis on job creation can appeal to

moderates and conservatives, and coming from a union family is a point he

plays up. Republicans are getting ready to probe the possible underside of

Delaney’s business practices, such as predatory lending and profiting from

foreclosures, but these tactics didn’t seem to work for

Garagiola.

Delaney has shown he can tap into a large donor base to match

his own efforts. Friends who have already given to the campaign will no

doubt be asked for more, as will his former and current business

associates. Two dozen CapitalSource employees contributed almost

$50,000.

Delaney’s campaign manager, Justin Schall, has said the banker

will put no more of his own money into the race. But Mooney scoffs at

that, saying odds are he’ll put in millions more.

Other wealthy people running for high office for the first time

have squandered millions on races in Maryland and other states, but

Delaney seems better prepared to do battle. Virginia’s Mark Warner has

shown the path on the other side of the Potomac.

April Delaney says people tell her, “I don’t know why you would

want to do it, but God help you for trying.”

Len Lazarick (len@marylandreporter.com) is editor and

publisher of MarylandReporter.com, a news website about state government

and politics that he founded in 2009. MarylandReporter.com staff writer

Glynis Kazanjian contributed to this article.

This article appears in the October 2012 issue of The Washingtonian.