Barack Obama has many qualities, but humility doesn’t appear to

be one of them. During his first term, he often came across as cocky or

crotchety about getting his way. Even when he signaled a willingness to

meet his opponents halfway, he could seem peevish. After he won

reelection, he seemed to take his victory as a personal vindication, not

as a chance to come together.

If Obama has appeared self-involved, he’s hardly exceptional

for his time. He grew up in the 1970s, the so-called Me Decade that

produced parents and teachers who—like the mythical but all too real

residents of Garrison Keillor’s Lake Wobegon—believed that all children

were above average. (Surveys show that American students lag behind those

of many nations at math and science but rank number one in self-esteem.)

Any honest accounting of modern popular culture must conclude that

old-time virtues of humility and self-effacement have been eclipsed by the

cult of celebrity, by personal “branding” and showing off on

Facebook.

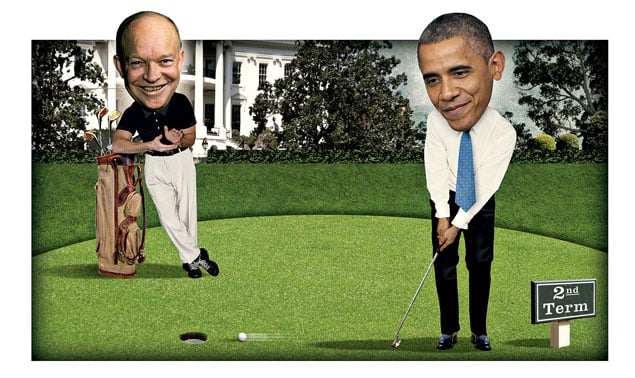

Obama may have to change his tone in the years ahead. If

history is a guide, he could be truly humbled by the curse that has

afflicted all two-term Presidents back to Dwight Eisenhower, more than a

half century ago.

In theory, a second-term President is free to be bold, to rise

above partisanship. He doesn’t have to worry about reelection, only about

his place in history. He can, it is hoped, do the Right Thing. In

practice, second terms have run the gamut from disappointment to disaster:

After Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, and

George W. Bush were reelected, they all were dogged by failed policies

and/or personal scandal.

If Obama wishes to avoid such a fate, he might take a page from

Eisenhower. By showing modesty and restraint, by keeping his ego in check

and working behind the scenes, Ike was able to accomplish a great

deal—keeping the peace, securing a strong economy, advancing civil

rights—even if he didn’t get much credit for his achievements at the

time.

True, Ike didn’t exactly glory in his second term. His approval

rating, which had floated around 70 percent, dropped close to 50 percent

in 1958, some 18 months after his landslide reelection. The Soviet Union

launched the first satellite, Sputnik, in October 1957, and

Americans were shocked and frightened that the Kremlin might now have

rockets powerful enough to rain down nuclear bombs from space. Eisenhower

was under tremendous political pressure to do something—to spend more on

rockets and missiles and to stand up to Communist aggression wherever it

occurred around the world.

Through it all, Ike kept his cool. Even though he was mocked in

the press for playing golf while the West seemed to be falling behind in

the arms race, he refused to respond to the hysteria. As he had all along,

he avoided small wars that could lead to big ones, instead bluffing his

way through standoffs against the Communists in Berlin and off the Chinese

coast. And while he spent more on advanced weapons systems such as the

Navy’s Polaris submarine, he knew that the Soviet missile capacity was

hyped, and he actually reduced defense spending over his eight years in

office.

Eisenhower was a balanced-budget man—he believed that long-term

security came from not spending or taxing too much, and he was willing to

put the country through a brief recession in 1957-58 rather than succumb

to the temptations of inflation that later seduced Johnson and Nixon in

their second terms.

Eisenhower’s legacy: a time of peace and prosperity. If the

1950s now seem a little boring, it’s partly because Ike made them

so.

Among Eisenhower’s greatest virtues were patience and

self-discipline. Of course, he had a huge ego—he couldn’t have become

Supreme Allied Commander in World War II without a healthy self-regard.

But as he once said, he succeeded by hiding his ambition and his

intelligence.

Ike could be vain: He used a sunlamp to stay “ruddy” in winter

and dressed impeccably, usually in suits he received for free from

admirers. He designed his own uniform, including the short-waisted

Eisenhower jacket, for reasons that reveal his canny self-deprecation. He

didn’t want to give the false impression that he was a warrior on the

front lines and was almost never photographed wearing a helmet or combat

gear in World War II. On the other hand, he knew that the smart jacket

showed off his athletic build. Unlike conspicuously medaled modern

generals, he wore few decorations—but then again, he didn’t need

to.

Ike is remembered for mangling his syntax at press conferences.

Forgotten is the fact that he had these briefings more often than any

other President: about every other week. He could play dumb when he needed

to. During a crisis with Red China in 1955, his advisers warned him to be

very careful about what he said to the reporters. “Oh, don’t worry,” the

President said. “I’ll just confuse them.” His private memos, it should be

noted, were always clear and to the point.

Eisenhower was endlessly patient. He never decided anything

before he had to, and he rarely telegraphed a decision. He was human, of

course, and his temper could flare. He tried to use golf to relax, with

mixed success. In April 1959, during the debate over whether the US would

fly the U-2 spy plane over Russia, Eisenhower threw a golf club at his

doctor, Howard Snyder, when Snyder tried to cheer the President on after

he muffed a shot out of a bunker. But Ike’s eruptions always passed and he

never bullied anyone. His tantrums were hidden from the public, who saw

only the genial, smiling President.

Eisenhower liked to retreat from time to time, to paint, read,

or watch westerns. (An admirer of the strong and silent type, he watched

and rewatched Gary Cooper in High Noon.) But whenever he faced a

difficult problem, he made sure to hear out all sides at formal and

informal meetings. He didn’t hesitate to jump into the debate, though

advisers sometimes couldn’t be sure when he was playing devil’s

advocate.

Operating in an age before cable TV and Twitter, Ike was able

to float above politics. He didn’t have to raise money to campaign; in

fact, he barely had to campaign for reelection in 1956. Congress wasn’t

quite as partisan in the 1950s—politics, it was often said during the Cold

War, stopped at the water’s edge—but Eisenhower did have to deal with an

obstreperous right wing in his own party. Today’s Tea Party may be

annoying, but it’s docile compared with the Red-baiting senator Joe

McCarthy, who intimidated liberals and moderates with his often baseless

but widely publicized allegations.

After Senate majority leader Robert Taft, Republican of Ohio,

exploded at the President in a meeting of legislative leaders during Ike’s

first spring in office, accusing him of wanting to spend too much on

government, Eisenhower took Taft golfing. The two were soon, if not

exactly friends, good working partners.

Barack Obama did once play golf with House speaker John

Boehner, in the summer of 2011, but the two hardly developed a friendly or

even a working relationship. The following summer, when it was reported

that Obama had played golf more than a hundred times as President, one

lawmaker at a session of the Democratic Senate caucus asked fellow

senators, “Any of you play golf with the President?” No one raised a

hand.

Obama is never going to be a gladhanding golf buddy. It’s not

his style. But Eisenhower, who didn’t like to be touched, wasn’t exactly a

backslapper, either. Rather, he was able to convey a genial, open

humility, a kind of guilelessness. Yes, it was partly an act—Eisenhower,

Richard Nixon once said, “was a more complex and devious man than most

people realize”—but all good actors become comfortable in their role over

time. Part of the job of President is to set a style, to project a way of

being. Eisenhower was confident but never self-important. Rather, he had

the confidence to be humble.

For years, Eisenhower’s reputation languished. He was seen as a

caretaker President, a dull, golf-playing, grandfatherly figure—an image

that the followers of John F. Kennedy effectively fostered to cast Ike as

a foil to the vigorous, young JFK. Scholars have long known better—in the

early 1980s, Fred Greenstein of Princeton described Ike’s “hidden hand”

governance—but only lately has the wider public begun to reevaluate Ike’s

legacy, through a number of biographies (including one I wrote) and partly

because Ike’s moderate, good-government Republicanism stands in stark

contrast to our current hyper-partisanship.

Eisenhower, typically, was offhand about his place in history.

Asked how he wanted to be memorialized, he answered: “Just don’t let them

put me on a horse.”

Evan Thomas’s latest book is Ike’s Bluff: President Eisenhower’s Secret Battle to Save the World.

This article appears in the February 2013 issue of The Washingtonian.