Early last year, in the midst of a long ramble through the city, I remembered that I needed some toiletries and ducked into a CVS south of Dupont Circle. The building, I recalled as I stood inside, had once been the Cineplex Odeon Dupont Circle 5—it opened in 1987 and closed in 2008. In those years, the theater was a place of refuge, provided in two-hour increments. Standing in the store, I tried to conjure the feeling of losing myself in a movie again.

Maybe I could try to recapture some of the magic right there in CVS, I thought. I stared intently at a bottle of Head & Shoulders, hoping to lose myself in the moment, but I was not transported. Instead, the volume of the song playing in the store—ironically, the Counting Crows cover of “Big Yellow Taxi”— seemed to grow louder: “Well don’t it always seem to go, that you don’t know what you got ‘til it’s gone…”

When I was six years old, my parents and I walked up Connecticut Avenue to the Avalon to watch The Black Stallion, my first movie. Before that day, my screen time had been limited to The Electric Company, and Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood, which I watched on my parents’ tiny black and white TV. The Avalon smelled of buttered popcorn and had chairs more plush than any I had ever occupied, and the pictures were enormous and in Technicolor. I watched, enraptured, as a fire consumed a sinking ship, a boy and a horse thrashed in the water, and the black beast galloped thunderously on a desert island and, later, around a race track.

A few months later I saw Superman II from the balcony seats of the Uptown. Time stood still as Superman saved Paris from a nuclear bomb, carried Lois Lane through the evening sky, forfeited his super powers for love, and then regained them in order to vanquish the three Kryptonian criminals in his icy fortress of solitude.

For the next few years, I accompanied adults to the movies they deemed appropriate for children. Once I was old enough to pay my own way, I spent many weekends during the George H.W. Bush years watching films. I saw Misery at the Embassy Theater in Dupont, The Silence of the Lambs at the Janus across the street, Goodfellas at the Tenley Theater and Speed at the Jennifer in Friendship Heights. My high school was across the street from the Outer Circle Theater on Wisconsin Avenue and, from time to time, I’d stop by by myself after school or on half-days. Once, when I was bored with class, I cut school to watch Kenneth Branaugh play Henry V.

Most of these theaters had funky interiors with small screens and floors that sloped at odd angles. The Janus had a pillar in the center of the auditorium, and one of the theaters in the Dupont Circle 5 had a poorly positioned ceiling sprinkler that cast a shadow on the top of the screen. I always felt a bit awkward as a I sat alone waiting for a movie to start, but once the lights dimmed and the curtain parted, I could tune out my surroundings, knowing no one was focused on me.

Occasionally, I’d screw up the courage to ask a girl on a date to see a movie. I watched Dick Tracy at the Mazza Gallery Theater with Donna, who had a nice sense of humor and ran on the cross-country team. I saw Avalon at the Wisconsin Avenue Cinema with Laura, a pretty, black-haired girl who was my year in school. I found myself able to make small talk in the theater as we waited for the show to begin, but I never knew what to do after the movie ended, sensing that something was expected but not knowing what it was. We would just go our separate ways.

For a few months in 1990, some friends and I attended the midnight showings of The Rocky Horror Picture Show at the Key Theater in Georgetown. Those who have never seen Rocky—“virgins,” in fan parlance—should know that the film is a cult classic, a parody of B-movie horror and science-fiction films made whole by audience participation. My classmates and I hurled vulgarities, rice, water, and toast at the screen, and we pelvic-thrusted along with Frank-N-Furter and his merry band of Transylvanian Transvestite Transsexuals during the show’s signature number, the “Time Warp.”

I spent most of the 1990s away from Washington—first in college and then in a job that took me from city to city. When I returned in the fall of 1999, unemployed and with time on my hands, I found the movie theaters waiting for me. I learned to put my loneliness and angst about my future at bay—at least so long as Lola ran, ran, ran through the streets of Berlin and John Cusack flung himself inside John Malkovich, before landing on the side of the New Jersey Turnpike.

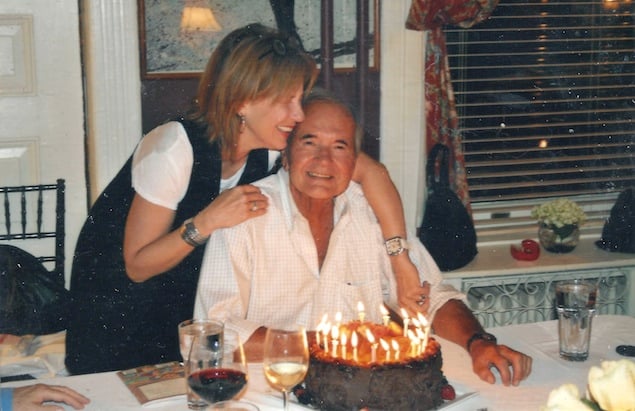

In April, 2000 I invited Rhona, a college classmate whom I had met at a friend’s party a few weeks before, to see The Sweet Lowdown at the Foundry—a theater in the basement of a Georgetown office building that showed second runs for $2. The movie turned out to be one of Woody Allen’s more forgettable offerings, and as we left the theater, I could feel the old nervousness creeping in—what to do next? Rhona broke the ice. “Would you like to have dinner?”

We went to a Vietnamese place and ate, had dessert, spoke freely, and enjoyed a slow walk back to the metro through the warm spring air. This turned out to be my last first date.

Ultimately, Rhona and I got married, had kids, and subscribed to Netflix. After our daughters were born—the demands of parenting and limited availability of babysitters being what they are—our movie-going plummeted. In the past six years, we’ve been lucky to see three or four films per year in the theater, and we usually stay close to our home in Silver Spring.

Our daughters are seven and four now, old enough for us to take them to the movies. Last January, I turned to the directory in the Post to look up show times for the new Muppet movie and did a double take. While I wasn’t paying attention, almost all of the District’s theaters had closed. The Avalon and the Uptown are still in business, but they are exceptions. Of the twenty DC theaters showing films in February 1990 when I was sixteen (the year that I consider to be my movie-going high water mark), only three remain open today.

The theaters that have been shuttered were mostly two- or three-screen establishments, some of which showed new releases but many of which showed art-house films or second runs. In their place, the District now has seven commercial movie theaters, mostly multiplexes. The AMC Loews Georgetown has fourteen screens, the Regal Place Cinema has another fourteen, and the Landmark E Street has eleven.

Empirically speaking, theater consolidation has not dramatically reduced the number of movies showing, screens available, or show times. I compared the movie listings for a weekend in February, 1990 with one in February, 2012 and found that, although the number of theaters had plummeted from 20 to 7, the number of films showing was about the same (37 in 1990 vs. 31 in 2012) and the number of individual show times actually increased from 235 in 1990 to 243 in 2012. This is because movies used to start in the late afternoon, and now theaters play them starting mid-day and even in the morning.

But the data seems beside the point. Only the most myopic bean counter could overlook the adverse impact that the wave of theater closings has had on Washington DC’s cultural life.

For one thing, consolidation means that whole neighborhoods have lost the comfort of having a nearby theater. Dupont Circle held three theaters in 1990 and now has zero. Capitol Hill, Palisades, and Tenley are without local theaters. New cinemas have opened in Penn Quarter, which had none twenty years ago, but whole swaths of Northeast and Southeast still don’t have easy access to the movies.

It wasn’t always this way. Cinemas like the Senator Theater on Minnesota Avenue, NE or the Newton Theater in Brookland opened in the 1930s and 40s but closed back in the 1960s and 70s, as neighborhoods outside the District’s favored quarter deteriorated.

And although most of the newer theaters have plenty of screens and space, places like the Mazza Gallery 9 and the Regal Gallery Place Stadium are buried in the bellies of malls. They do little to activate street life or help to define their neighborhoods.

The demise of local theaters means it’s less possible then it used to be for a bored DC teenager sitting at home on a weekend afternoon to walk down the street on the spur of the moment to his nearby cinema. DC’s gentrification has created plenty of neighborhood gastropubs and wine bars, but these venues are not viable entertainment options for people under 21 years old.

I miss having options. When it came to going to the movies as a teenager, on any given weekend I could choose to visit a different neighborhood either by myself or with friends or a new girl I admired. I may not have had much cash in my pocket, but the experiences at my finger tips seemed plentiful. As I’ve aged and taken on more professional and parental responsibilities, my time has become increasingly consolidated in the twin theaters of office and home. Both venues offer many hours of drama and comedy, and I’m happily focused on being an employee, husband, and father. At the same time, I mourn the loss of variety—the spice of life, they call it—and the freedom to roam.

One clear morning in February, gripped by nostalgia and wanderlust, I skipped work and tramped around the city with a copy of the Post movie listings from a weekend in 1990, to see what had become of the theaters I remembered. In a few cases, such as with the Embassy Theater, the buildings sit vacant and forlorn, with “Now Showing” marquees that have been blank for years. But in most instances, life has moved on, and the spaces have been put to other uses. The Foundry is now occupied by offices, the Jennifer by a beauty salon, the Janus by a clothing store, and, of course, the Dupont Circle 5 has become a CVS—as have The Biograph in Georgetown and the Macarthur Theater in Palisades. Consider it the durg-storefication of my youth.

In some instances you would never know that a theater had been there at all. The Outer Circle has been demolished. A bank branch stands in its place. The Phoenix 9, which was located in the food court of Union Station, has vanished completely, replaced by a brick wall (I like to imagine that the theater has been entombed and that one day archeologists will break through the wall to find mummified popcorn and dusty reels of Shrek 2).

By late afternoon I had become weary and somewhat disoriented from miles of walking. The setting sun’s glare made the buildings across a street hard to see, and I began to feel lightheaded. Clues that a building once held a theater—a commercial sign that once contained show times or the foyer that once housed a ticket-taker’s booth—seemed to appear and disappear before my eyes. Had I really seen Goodfellas here, or was I imagining things? Would the theater appear again one day, like in Brigadoon, only to vanish into the summer smog? As I walked through the city, I imagined that the store clerks, bank tellers, and office workers now laboring in these buildings were haunted by the ghosts of Cineplex past. That every so often, in the pause between the end of one Light FM track and the beginning of the next, they could have sworn they heard voices coming faintly from the other side of the wall:

“Have the lambs stopped screaming, Clarice?”

“Pop quiz, hotshot. There’s a bomb on a bus.”

“By the way, I took care of that thing for you.”

“Let’s do the time warp again!”

David Schneider is a civil servant who lives with his family in Silver Spring. He blogs at http://araspberry.blogspot.com.