At the time, I didn’t think I’d done anything wrong. Now I

can’t get it off my heart.

Aunt Eleanor was the beauty of the family and a stickler for

doing things properly. Did we write a thank-you note? Did we wait for the

hostess to pick up her fork before we plunged into eating? Did we open the

door for our grandmother, step back for elders, speak quietly? We were all

a little frightened of Aunt Eleanor.

Then her husband, an admiral, retired, and she developed (when

she was almost 70—ridiculous!) an ambition beyond the polish on the silver

tea service and the luncheons she gave for Navy wives. She wanted to

write.

It was 1975, and I was a writer myself, so she asked me for an

introduction to Tom, a magazine editor I knew in DC. I was young, filled

with self-importance. I’d been part of the civil-rights and women’s

movements, bra-burning and blue jeans. Women cursed; men helped with the

dishes. What could Aunt Eleanor possibly have to say? Nonetheless, I asked

Tom to meet her: “Be good to her, okay?”

In hat, heels, and gloves, she stepped into the office crowded

with desks, the writers and editors typing or talking on phones. Finally

one girl glanced up. “I have an appointment at 11,” Aunt Eleanor

announced, hiding her terror with a snap of her chin.

“He’s on the phone,” the girl said. “Go on in.”

-

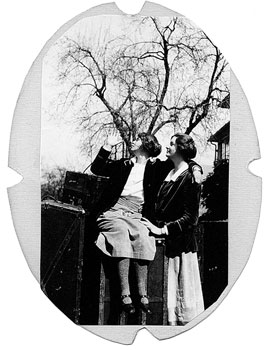

Early 1920s

Eleanor Parrish Snyder (left), born 1906, went to Middleburg’s Foxcroft School.

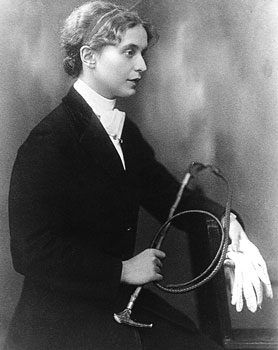

Photographs courtesy of Sophy Burnham.

Next >> -

Mid-1920s

Eleanor is shown as a young woman in riding gear.

-

1929

She wed the grandson of Confederate colonel John S. Mosby.

-

Late 1950s

Aunt Eleanor (center) with her two sisters.

-

1979

Eleanor Coleman a few years after her meeting with the DC magazine editor.

$('.first-pair').click(function(){ $(this).parent().parent('ul').animate({'top':'0'}); }); });

Aunt Eleanor stepped to the door, and Tom, the phone at his

ear, gestured to a chair. He leaned back, feet on his desk, as she removed

the papers from the only other chair and sat down, manuscript in her lap.

I don’t know what her article was about—perhaps her father, born in

Washington before the Civil War, or something to do with being a Navy

wife.

Tom was a burly Irishman, his tie askew. He joked into the

phone, swiveling around occasionally to grab a paper from a file cabinet

but always returning his feet to the desk, soles in my aunt’s face. He had

no malice. He was playing his role in The Front Page, and Aunt

Eleanor was the audience.

When she left, Tom was riffling through papers. When he

noticed, he was instantly sorry. He hung up and walked to the outer office

to ask about his guest, only to be told she’d departed without a

word.

After that, she gave up writing.

Aunt Eleanor has died. Tom has died. At the time, I had no idea

what courage it took for her to brave that world. I apologized to her on

Tom’s behalf but never insisted he write a proper apology, ask for another

meeting, give her an assignment.

She could have written about Washington when, as a little girl

in black stockings and a sailor dress, she walked with her mother and

sisters down 16th Street to leave a card at the White House for the

President’s wife, who apparently had no social life. The card was turned

down at the upper left-hand corner to show it had been delivered

personally rather than by a servant. Later the First Lady sent a card

inviting the family to a White House tea.

She could have written about riding her pony into Georgetown as

a child to visit a friend, about seeing her parents off to a dinner party

with the First Couple at Decatur House when it was still in private hands.

About living in Ecuador with her naval-officer husband or in postwar

Japan.

How arrogant I was to imagine that my aunt had no dreams,

adventures, or skills. How I wish that I had it to do all over

again—properly.

Sophy Burnham is the author of 13 books, including A Book

of Angels and her most recent, The Art of Intuition. She can be reached

through sophyburnham.com.

This article appears in the March 2013 issue of The Washingtonian.