Did you know that one of the most decorated combatants of World War I was a terrier named Stubby?

As I wandered through a labyrinth of display cases at the National Museum of American History, I felt like an excitable schoolchild on a field trip. I was on a quest to find the oddest, most exotic items in the Smithsonian’s collection, and as I approached Stubby’s display case, my inner child was bursting with trivia.

Did you know that Stubby was awarded the equivalent of a Purple Heart and in fact received enough medals (more than a dozen) to cover a whole doggie vest? Did you know he could salute his superiors by raising his paw to his eyebrow? That he took shrapnel in the chest and leg? That he got gassed and then became a valued sentinel against gas because he could smell it before anyone else? Did you know he captured a German spy by cornering him and snarling and that this earned him a promotion to sergeant? And that, after returning home, he met multiple US Presidents and became the mascot of Georgetown University?

Having built things up so much, I half expected to find a shrine to Stubby. Instead, he sat in a crowded display case, beneath a burned-out light bulb. Unlike his pictures online, he was naked—no vest of medals. Worse, while another animal in the case—a one-legged messenger

pigeon—got front-and-center billing, Stubby sat near the wall. The placard below him said little—no mention of shrapnel, spies, or Hoyas.

Did you know you can feel crestfallen for a dog that died nearly a century ago?

The reason you learn so little about Stubby in the museum can be summed up in one number: 137 million. That’s how many items the Smithsonian owns. Only around 1 percent are on display, but that still leaves more than a million to take in. It’s a cliché to say you could spend a whole week wandering through the various Smithsonian museums and still not see everything. But it’s a cliché because it’s true. You get overwhelmed, and it’s easy to overlook even the likes of Stubby.

Hunting down the Smithsonian’s most outlandish items was my antidote to weary neglect. I wanted to single some things out—to savor them and learn their stories.

Doing so proved tougher than I imagined, and not just because of the number 137 million. A research institution like the Smithsonian gets understandably sore about being perceived as nothing but a warehouse of weird things—a Ripley’s Believe It or Not museum with nicer architecture. So when I started prodding officials about the oddities in their collections, some of them clammed up. A few refused to speak to me.

Still, people naturally love the bizarre, and a few curators graciously opened up about the exotica in their collections. I wanted to focus on neglected items, things you walk by without noticing or that you can’t notice because they’re packed away in storage. But my most important criterion is best summed up by Kathy Golden, the curator who helped get Stubby on display. “He tells a story,” Golden says. “He’s not important like Lincoln’s hat or Jefferson’s Bible, but he tells a story.”

• • •

The Smithsonian owns many firsts. The first cash register, the first margarita machine. The first integrated computer circuit and the first musical instruments used in space (a harmonica and a set of sleigh bells, which played “Jingle Bells” aboard Gemini 6). But the numero uno that caught my attention was the world’s first—and only—pigeon-guided missile system.

Psychologist B.F. Skinner had grand plans for Project Pigeon. Pilots during World War II had no way of aiming missiles—they just dropped them and hoped for the best. An expert on conditioning animals, Skinner decided to train pigeons to steer missiles from the inside. Doing so would certainly shorten and might even win the war for the Allies, he argued.

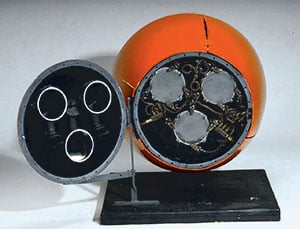

The military had doubts, but it gave Skinner $25,000 to build a prototype nose cone, which the Smithsonian now owns. It’s a gumdrop-shaped device about two feet long, painted hazard orange and silver.

Skinner took advantage of the pigeons’ natural tendency to peck things with their beaks. He showed them pictures of enemy ships or ammunition depots, and if they pecked the target, they got a pellet of grain. Eventually the birds could recognize targets without prompting and would peck them repeatedly. Their task inside the nose cone was the same. The cone swings open to reveal three cylindrical coves, each about six inches tall. A single pigeon sat inside each cove, and collectively the birds acted as the missile’s eyes.

In final design, they would have viewed the outside world through a primitive touchscreen. The birds would peck at any targets they saw. If the peck struck the middle of the screen, the missile would stay on course. If it struck off-center, air valves would open and adjust the flight path.

What ultimately doomed Project Pigeon wasn’t the birds. For all their despicable qualities, pigeons proved adept at steering missiles: They’re easily trained, have excellent eyesight, don’t get distracted, don’t get nauseated in freefall, and would keep peck-peck-pecking away at enemy targets even while being exposed to deafening bangs. Instead, the project failed because the missile’s steering systems couldn’t keep up with the birds’ quick, precise instructions.

After the war, advances in electronics made the kamikaze pigeons seem ridiculous, and that’s why the bright-orange nose cone sits in a closet in the American History museum. The nose cone nevertheless remains important to psychology, curator Peggy Kidwell says, because it represents a major shift in Skinner’s thinking. Before the war, he was a timid lab scientist, content merely to describe animal behavior. His success in training pigeons inspired him to think about engineering and controlling behavior, including in humans. He became an outspoken proponent of conditioning people, especially children, and went on to become one of the most influential psychologists in history.

The nose cone also helps remind us, Kidwell says, “how the entire American society was mobilized during World War II.” Pigeons had long carried messages during wars, but to even consider them as active combat participants, she says, “is symbolic of the desperate straits and national concern for missile guidance.”

Just before we part, Kidwell mentions another way World War II affected US society: the shortages, especially of luxury goods like silk. She suggests another odd item to track down a wedding dress fashioned from the only source of silk available to most Americans in the 1940s: a GI’s parachute.

• • •

The Smithsonian, in fact, owns two parachute dresses and has one on display. But curator Nancy Davis wants to show me the dress in storage, the one with bloodstains. To reach the dress, Davis leads me into what looks like the world’s largest walk-in closet, with row after row of white cabinets. At a glance, I guess that the cabinets are stuffed with jeweled robes, or maybe all the Oscar winners’ dresses—extraordinary things. Instead, most are full of everyday clothes—regular old blouses and pants, even vintage T-shirts and bras.

“It’s the everyday things—the underwear, the things that get used up—that are really valuable,” Davis says. “They tell how people lived their lives” in decades and centuries past. That’s well and good, but this emphasis on everyday clothing (and underwear) has one unintended consequence—standing there, you feel awfully self-conscious about what you left the house wearing that morning. Is this how posterity will judge me?

However important the everyday is to museum research, it’s the extraordinary that captivates people, and a parachute transformed into a wedding gown is pretty extraordinary. As Davis dons gloves and unfolds the dress, even I—a man who doesn’t know his ruffles from his ruches feel stirred.

The original owner, Major Claude Hensinger, bailed out over Japan in 1944 after his B-29 caught fire. He landed on some rocks, suffering minor injuries, then used the parachute as a pillow and blanket that night. Upon returning home to Pennsylvania, he began courting a woman named Ruth, then proposed to her by giving her the parachute and asking her to make a dress of it.

Davis points out the garment’s elegance—its design was inspired by Gone With the Wind. Still, it retains some vestiges of its former existence. It has heavy-duty parachute seams, and it’s extremely billowy: When Davis starts folding it back into the box, I’m doubtful it will fit.

Somewhere between his crash landing and his rescue, Hensinger bled on the parachute, and while you’d think bloodstains would be easy to find on a wedding dress, Davis and I can’t locate any. At last, we spot them—a few darkened drops in the middle of the back.

Claude and Ruth’s daughter also got married in the dress in 1973, as did their daughter-in law in 1989. All three women, then, had a drop of Hensinger’s blood near their hearts during the ceremony. Not even a fairy tale could improve on that detail.

For whatever reason, when you start digging into oddball items at the Smithsonian, animals come up a lot, even in departments where you’d never expect them to—such as currencies.

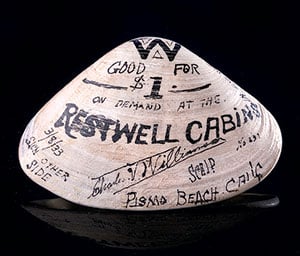

Among other strange money, curator Karen Lee at the American History museum shows me a bill from Washington state made of salmon skin and a bill from Oregon made of sheep’s hide. But the strangest currency on the table is the clamshell cash.

In March 1933, to stop a rash of bank runs, President Franklin Roosevelt closed banks nationwide for four days. Whatever its fiscal merits, the decision proved a pain for everyday people, who lacked access to cash. So the residents of Pismo Beach, California, got creative.

Merchants at 11 businesses scooped up clamshells from the seashore. They declared the biggest shells the most valuable, then transformed them into genuine currency—dating them, signing them, even inscribing them with “In God We Trust.” Lee says she sees the clam cash as an exemplar of human ingenuity: “In times of desperation, people said, ‘We need to work this out,’ and they did.”

Naturally, the Smithsonian’s National Zoo has squirreled away some animal oddities as well. But zoo officials hesitated to talk about the strangest item in their possession—unless I made it clear that their remote-controlled badger wasn’t a toy but was built for serious research.

In the late 1980s, a car in Wyoming hit a 20-pound badger. Its remains, packed in dry ice, arrived at the National Museum of Natural History the next day, where scientists skinned it and mounted it onto a remote-control truck. The top half of the amalgamation looks like your typical black-and-white badger; the bottom half is four oversize Tonka wheels. The badger bares just enough teeth to look fierce, and its front and back legs stick out kind of like Superman’s.

So what serious scientific purpose does this robo-badger serve? It’s a fake predator. The zoo has a campus 70 miles west of DC, in Front Royal, where biologists help conserve species. In the late 1980s, one project aimed to reintroduce the endangered black-footed ferret into the wilds of Wyoming, Montana, and South Dakota. Problem was, the ferrets, raised in captivity, had never encountered a predator and would have become ex-ferrets pretty quickly if turned loose with no training.

The robo-badger was enlisted for predator boot camp. Biologists periodically “attacked” the ferrets with the all-terrain badger while also shooting them with a rubber-band gun, to reinforce in their little minds that badgers equal pain.

Retired Smithsonian zoologist Chris Wemmer remembers that, at two months old, the ferrets “were as helpless as gumdrops,” but they developed a healthy fear response on their own by four months. A single bad experience with the robo-badger (and there weren’t many good ones) boosted their natural instincts. As Wemmer later wrote on his blog, “a good scare improved the survival response, which was simply to beat a hasty retreat down the burrow.”

Unfortunately, the training didn’t translate all that well to the wild. Before exposing the endangered black-footed ferrets to potential harm, the biologists trained some non-endangered Siberian ferrets with the robo-badger and turned them loose. Predictably, perhaps, real predators proved more clever than your average remote-controlled carnivore, and the Siberian ferrets died out. (A better boot camp involved a pet Labrador.) Still, the robo-badger played a role in what became one of the Smithsonian’s most successful conservation efforts ever. Today more than 1,000 black-footed ferrets roam the West.

• • •

In contrast to the robo-badger, the final animal oddity on my list seemed like pure frivolity. But even the “squirrel frame” proved significant in its way.

This object is just what it sounds like: a small frame surrounded by a flattened pelt, complete with claws and a desiccated head. Inside it sits a (probably bogus) newspaper column about a deck of cards made of human skin. An archivist named Lorain Wang discovered the frame in 2005 at the Smithsonian’s Museum Support Center in Suitland.

It was Wang’s first day of work, and while cleaning out her office she found a manila envelope. She peeked inside, saw fur and claws, and screamed. Wang says archivists occasionally find unpalatable things in old boxes—she once came across an empty box labeled “horse meat patties.” Never dead vermin, though. And because the Museum Support Center houses 55 million objects, no one knew the frame’s provenance.

For years, it migrated among various people’s offices, until another archivist found a clue in 2011. It turned out that the frame had belonged to, of all people, Marjorie Merriweather Post, the socialite and benefactor of Hillwood Estate, her palatial former home in Northwest DC.

Perhaps you’re different, but I’ve never thought, while touring Hillwood’s Fabergé and china collections, “You know what would look fabulous right over there . . . ?” In reality, Post hung the squirrel frame in the main lodge of her 68-building “rustic retreat” in the Adirondacks. (Each guest house had its own butler and maid.) The lodge also contained important Native American artifacts, and when Post’s estate donated them to the Smithsonian in the 1970s, the squirrel frame got swept along.

It now rests in an archival box. There’s no plan to display it. Still, it’s valuable. After touring her immaculate DC estate, I could never have imagined Post even touching fur that wasn’t mink or ermine. But I was wrong: She had a sense of humor. It took a dead squirrel to make her seem alive to me.

• • •

The Smithsonian owns some shrunken heads from South America. It owns a Tibetan kapala, a ceremonial cup made from a human skull. It owns the “soap man,” who died in Philadelphia circa 1800 and much of whose body, because of the unusual chemistry of the soil in which it was buried, was transformed into something like a giant bar of Ivory.

None of those items is on display. Human remains have become a touchy subject for museums. As a result, Smithsonian officials forbade me from seeing them. That said, not all human remains are equally sensitive topics. People do sometimes make a spectacle of themselves, with good

humor, and in those cases—as with Hans Langseth’s 17½-foot beard—curators were happy to let me peek.

Langseth, a farmer from North Dakota, started growing his beard around age 30, in 1875, possibly for a Centennial Day contest. There’s no record of whether he won for having the longest whiskers that day, but he certainly beat everyone over the long run, eventually setting a Guinness-certified world record. Today the beard rests in a cabinet of skulls and other bones in the Natural History museum. It’s mounted on a piece of blue cardboard and snakes back and forth (and back and forth) along the surface.

Most long beards are bushy, but Langseth’s is compact, like a rope. For most men, facial hair grows just eight inches or so before it falls out. Langseth’s stayed in place only because the strands got matted together as they fell out. “It’s essentially one big dreadlock,” says

David Hunt, an anthropology-collections manager.

The beard changes color along its length. The distal end, from Langseth’s youth, is chestnut. But the color bleaches away as it meanders, becoming white-blond near where it attached to his chin when he was 81 years old. (White hair slowly turns blond after death.)

The Smithsonian once displayed the beard for the public—Hunt still has the portrait of Langseth’s face from which it dangled—and Langseth himself showed it off during his lifetime. Film footage exists of him letting onlookers stroke it; at one point, he appears to fish with it. He even joined a traveling circus and greatly enjoyed the attention. (He eventually quit the circus because people kept yanking on the beard to see if it was real. Also, when the Fat Lady started coming around every evening to groom it, Langseth’s wife got jealous.)

The beard could be an important tool for research, Hunt says. Hair preserves DNA well, and it’s rare to have access to DNA samples from so many points in one person’s life. Studying it could help researchers understand how DNA changes over time. Forensic scientists also take a keen interest in how hair ages, and there’s nothing else quite like Langseth’s beard.

• • •

The Smithsonian has always been a miscellany. Its first building, the “castle,” opened in 1855, and housed mammals and meteorites, steam engines and gems, marble sculptures and basalt idols, all under one roof. Buffalo roamed the back yard in a pen, and owls nested in the towers.

In the 158 years since, the Smithsonian has found room for a steam-powered adult tricycle from the 1880s; a violin that served as a Civil War diary, with entries etched into the back; and a prized set of jewel-encrusted trinkets, including a pacifier, a yo-yo, a mousetrap, and a sardine can. There’s a stretch of pavement from Route 66, a cache of Y2K memorabilia, and Evel Knievel’s motorcycle. There’s Abraham Lincoln’s top hat and his handball; Theodore Roosevelt’s writing desk and his original teddy bear; John Glenn’s spacesuit and the tube (yes, tube) of puréed beef he carried into orbit.

Some at the Smithsonian may bristle about its reputation as “the nation’s attic,” but it’s not a term of disparagement. Attics are where we store things we love and can’t bear to part with, even if we aren’t sure why. We know things will be safe there, and for that reason attics are just as important psychologically as physically.

The parachute dresses and clamshell cash and pigeon nose cone probably won’t change our understanding of American history much. But once you know that such things exist, history does look more colorful. They expand the realm of what’s possible and our notions of just how creative—and weird—human beings can be. And while the most valuable goods for historians may indeed be the everyday, some of us will always have our eyes peeled for the extraordinary.

Sam Kean is author of the nonfiction books “The Disappearing Spoon” and “The Violinist’s Thumb.” His website is samkean.com.

This article appears in the July 2013 issue of Washingtonian.