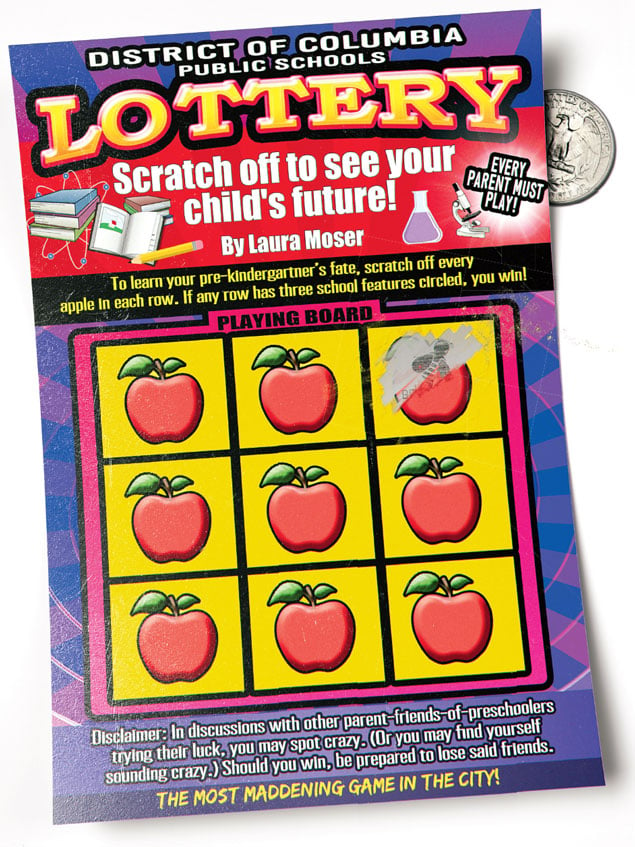

Back when my eldest child was an infant and the DC Public Schools lottery was abstract and uninteresting to me, a neighbor confessed one day that she’d hit the jackpot: Her three-year-old son had scored a slot in her first-choice school. “You must be so relieved!” I exclaimed.

“We are,” she said after hesitating a second. “But now several of my close friends won’t talk to me—they’re just too upset.”

The only lottery I’ve ever won was a $100 scratch-off card at age 16, and the 7-Eleven clerk who sold it to me said I was too young to claim my winnings. (I later dispatched my father to redeem it at a nearby Texaco.) Given my friend’s experience and my own dismal record at bingo halls and raffles over the years, I suppose I should have approached my son’s first school lottery a couple of years ago with a little more data under my belt.

At the time, my husband and I were debating whether to move back to New York or to dig in and buy in the District. Our temporary sublet was on East Capitol Street, which a quick web search revealed was in-boundary—or IB, in DCPS lingo—for Maury Elementary. Maury? I couldn’t believe my luck. Maury was one of the most sought-after schools on the Hill; I’d visited once, briefly, and loved it instantly. How brilliant was I?

My son was almost three, and I was determined to get him a spot in the District’s universal pre-K program. School for three- and four-year-olds is free in the areas where it’s offered, but even if you live within the geographic boundaries of a neighborhood school, you have to take part in the lottery because the slots are limited.

A few more seconds of Googling turned up the hitch: Only the northeast side of our block of East Capitol was zoned to Maury. Our side, the southeast, was zoned to the Hill’s least sought-after school.

Whatever, I thought. We were still way better situated than most OOB—or out-of-boundary—families. That’s because we’d be OOB with a proximity preference: Our sublet was less than 3,000 feet from the school. In the DCPS lottery hierarchy, that meant our kid would rank lower than an OOB applicant with a sibling enrolled there but higher than the OOB masses who lived more than 3,000 feet away. Not bad.

I put in for Maury and five other DCPS schools, plus about half a dozen charter schools, none of which I’d visited and many of which I couldn’t have located on a map—but all of which sharp-seeming parents at playgrounds had praised within earshot. That was the strategy my more experienced parent-friends had recommended: Just throw everything at the wall and see what sticks.

By the time the results came out, my husband and I had closed on a house near a top-notch Metro stop and dozens of fabulous restaurants but nowhere near Maury, which still loomed large in my fantasy life. And abracadabra: We (or our kid, I should say) got in nowhere—except the failing school near the East Capitol Street house we had left.

A few months later, after settling into the new house, I called the office of a reputable school that had wait-listed us in the high double digits. We now lived within 3,000 feet of it, and I wanted to know if our new permanent address would bump us ahead of the other OOB families on the list.

“No,” the woman who answered said, “but we just had a girl withdraw from the three-year-old program today. Want her spot?”

• • •

Two years later, I’m still grateful I made that phone call. We took the slot that we got not out of luck but through administrative laziness, and the school has turned out to be a perfect fit for my child.

While my friends rave about the every-child-is-a-Picasso programs at their kids’ pre-K, I’ve found that the more academic focus of ours suits our nerdy little boy. He has recess several times a day and still brings home plenty of inscrutable artwork, but by the time he turned four he was already puzzling out “lost dog” on street signs and “low fat” on milk cartons. I’m a writer, so by God, I liked that.

You’d think, then, that I’d be done for good with the soul-crushing purgatory that is the DC Public Schools lottery, right?

• • •

Lottery season, which this year lasts a seemingly interminable 3½ months—beginning December 16 and ending March 31, when results are published—breeds a peculiar blend of hysteria, fear, and desperation in us helpless parents forced to participate in it. Especially in my part of the city, EOTP. (That’s East of the Park, as in Rock Creek Park, as the hive mind puts it on DC Urban Moms, an online forum for all things parenting.)

Consider the car-less Columbia Heights couple who applied to 16 schools and only got their kid into one, requiring a trek that adds two hours to their daily commute. Or the Mount Pleasant parents who went 0 for 6, four years running, for their eldest child, then lucked into one of the hottest schools in the city on their first lottery entry with their youngest. One mother I spoke to spent the first four years of her son’s life in her cramped premarriage one-bedroom apartment (and indefinitely delayed having another child) just so he’d have the right address when lottery time rolled around. Then there was the woman who seriously contemplated signing a lease on an English basement that was in-boundary for Maury, to increase her child’s chance of getting in there. (All right, I admit this last person was me.)

The basic problem is supply and demand. DC is in the midst of a baby boom: Between 2010 and 2013, according to the US Census, the number of children under age five jumped from 33,000 to 39,000, an increase of 20 percent. While schools are expanding, the desirable ones just aren’t growing fast enough to keep pace with the population.

For next fall’s kindergarten class at Brent Elementary, which has the best test scores on Capitol Hill, there are three open OOB spots. The school had 185 hopeful applicants last year, 129 the year before. Janney Elementary, a crown jewel in the so-called JKLM (Janney-Key-Lafayette-Murch) constellation of Northwest DC neighborhood schools, with reading and math scores generally above 90 percent, reports zero OOB kindergarten slots for next fall—it fielded 181 applications in 2013 and 221 in 2012. The good news: dip in demand! The bad news: still no spots.

In-demand charter schools—and what makes them so in-demand is nebulous—generally have waiting lists that climb toward the 500s for pre-K. (This even though some of these charters have been around only a year or two and have no significant testing data to show for themselves.)

Another problem: bureaucratic dysfunction. A decade ago, each school filled its roster willy-nilly, according to criteria that principals came up with on their own. Seats were first-come, first-served. To get their kid into one of the high-performing but perennially packed neighborhood schools west of the Park (WOTP), parents made an annual ritual of pitching tents and camping out the night before registration opened.

DCPS didn’t introduce an online lottery until 2005 (and even then it was limited—not all schools participated). For the first few years, parents would list their school preferences in no particular order; a few years later, they were allowed to rank their picks. But bizarrely, every neighborhood public school ran its own distinct lottery. So a child’s number could get drawn first at, say, five places, while his best friend might end up with waiting-list numbers in the 100s at every school he tried for. The luckier (read: intolerably smug) parents might hold onto multiple spots while others scrambled to find backup child care for the year to come.

The admission process for public charter schools, meanwhile, was totally separate. The applications took almost zero effort to complete, and you could fire them off to all 30-something elementary charters if you wanted. Why not? It was like online shoe shopping—no credit card required.

By dint of a remarkable innovation last year, if a child got into one of his higher-ranked DCPS choices, he’d be dropped from the waiting lists of those he’d put lower. This measure helped trim the massive wait lists that always remained clogged up well into summer and fall, until the so-called September shuffle started. That’s when you would see seismic movements on many waiting lists; even kids with a number in the mid-100s might still get into a school.

Only the most dedicated can put up with this insanely frustrating system. The savvier of these employ elaborate stratagems. Take Michelle Martin, a 41-year-old Department of Justice employee who took the opposite path of most Washington parents: She and her husband fled the suburbs for the District after having a baby, because, she says, “I didn’t want to raise my child in Virginia, where every single one of my neighbors looked exactly like me.” After her daughter turned two, Martin acquired a spreadsheet full of school information from a neighbor downtown. She built out the document with even more data and started sharing it on listservs.

Despite all her toil, Martin’s daughter got in nowhere the first time she entered the lottery. “I was so upset,” Martin says, “especially since two of my friends who used my spreadsheet got into LAMB [Latin American Montessori Bilingual Public Charter School] and Inspired Teaching.” Martin ended up on 15 waiting lists.

Finally, at the beginning of the school year, her karmic reward materialized: “We got into Bethune, LAMB, Bridges, Creative Minds,” she told me before pausing, trying to remember if she’d left any schools off this dazzlingly impressive (and mildly sick-making) list.

This year, a Nobel Prize winner is coming to our rescue. An organization chaired by Alvin Roth, a Stanford professor who shared the 2012 economics prize for tackling similar real-world problems—figuring out how to match med students with their desired residency programs, for instance—has designed a unified lottery for DCPS.

Rather than holding separate ones at every school, there will be one mega-lottery, with all DCPS schools and a majority of charter schools participating. Families will rank their picks from 1 to 12. Everyone receives a tracking number, and after the lottery closes on March 3, a computer pulls numbers in random order.

Roth’s “deferred-acceptance algorithm” will then attempt to match each child, in the order his number was drawn, with a seat at his top pick and then, if no seats are available, at his second-ranked school and so on until there’s a match. The randomness of the number-drawing is weighed against factors such as living in-boundary or having a sibling at the school. It’s complicated, yes, but far more equitable than the past free-for-all.

Each kid will be offered only one spot. “The lottery isn’t going to change the total number of seats,” deputy mayor for education Abigail Smith says. “But it will more efficiently match kids so that more kids will end up with a seat initially.”

The lucky applicant who gets into her number-one choice will be dropped from all waiting lists. The applicant who gets into her fourth choice will be wait-listed at choices 1 through 3 but not 5 through 12. The lottery organizers emphasize that there’s no point in trying to game the system. You simply rank your schools in the order you truly want and are matched accordingly—or not.

I haven’t talked to a single parent who doesn’t consider these changes both exciting and daunting. For the first time, we have to think really hard about how to order our choices and put in the work required to vet them: hours of online research, endless schleps to evening and weekend open houses, countless more minutes trying out hypothetical commutes, until, inevitably and almost always regrettably, you find yourself trolling the mommy listservs.

“Why is everyone making this so complicated?” a poster on DC Urban Moms railed recently. “Rank [the schools] in the order of your preference and keep a couple at the bottom of the list that are safeties in case you don’t get into your first choices. If you use any other strategy, you are an idiot who deserves what you get. Furthermore, your child is doomed to be educated poorly because his parents can’t follow simple instructions.”

• • •

Even though my husband and I were ecstatic about our son’s school, I decided to try my luck again last year. Why? I had trouble explaining the irrational decision to myself.

My son loved his friends and his teachers and seemed to be learning more than kids I knew at more sought-after schools. What did he care if bitchy online commenters were always dissing his school? My lived reality bore no relation to their anonymously hurled accusations: that the African-American principal had publicly claimed to want “more of her own” at an already predominantly black school; that its impressive test scores—second-best in a neighborhood full of solid counterparts—obviously resulted from systemic cheating; or that the school rudely banned neighborhood families from its baseball fields during the summer of its massive renovation.

I suppose I reentered the pre-K lottery last year because that’s what everyone else at our not-all-that-prestigious school did. Unless you’ve landed at one of the handful of places that a specific cohort of white, overeducated, “high SES” (i.e., high socioeconomic status) parents salivate over, you’re supposed to keep on spinning the wheel.

There is some comfort, at least, in knowing you’re not the only crazy (er, dedicated) parent obsessing over this stuff. Susan, an economist who lives in DC’s Brookland, has been researching schools for three of her four-year-old’s years on Earth. “I always joke that I’ve gotten a minor associate’s degree in education,” she told me.

But Susan’s deep dive led her to some blunt conclusions that troubled me. “In the beginning,” as Susan put it, “you spend a lot of time going through the official language, and then you figure out that’s not what it’s about. The real question is: What is the socioeconomic dynamic of the school? There are a lot of schools out there that are like red herrings. They look like good schools, but nobody sends their kids there. Why is that?”

I recognized this line of inquiry all too well. But surely it isn’t socioeconomic signaling that’s propelled me back toward the lottery?

I put in for three DCPS schools and one charter.

Initially, it felt good to have no real stake in the result. In the end, we fared poorly; our highest waiting-list number was 98. The day the results went online, I felt rotten—and for months afterward, I struggled to figure out why.

Maybe it was just that it sucks to feel like a loser. I mean, did the mother of one of my son’s soon-to-be-ex-classmates suddenly have to start taking a superior tone with me just because she’d lucked into one of the most popular charters in the city—which, by the way, I hadn’t even applied to?

This year, I’m more confused than ever. Part of me wants to renounce the lottery altogether, as a gesture of faith in the school that has been so wonderful for my son. But what if all his friends leave—then where will we be?

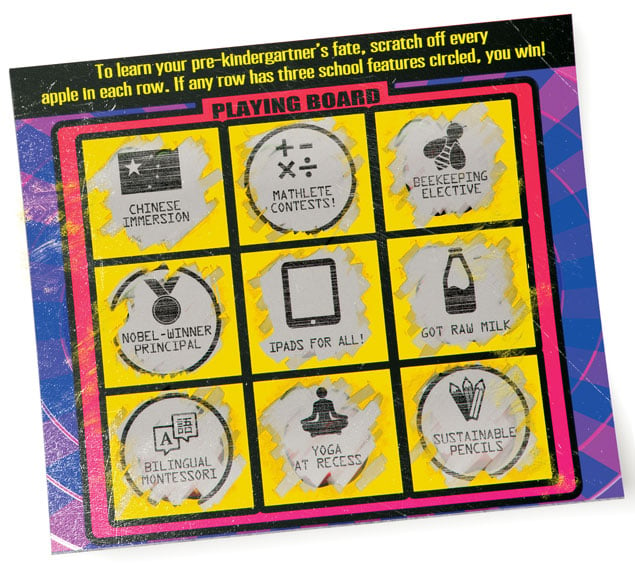

And if I do the lottery, what schools do I do it for? Contemplating the fathomless marketplace of pedagogical options—Hebrew/Spanish/French/Mandarin immersion, World Cultures, Tools of the Mind, International Baccalaureate, Reggio Emilia, Expeditionary Learning, Montessori, bilingual Montessori, “green” bilingual, and on and on—leaves me confused and dehydrated every time.

Should I send my child to the French-immersion program at E.W. Stokes because my brother lives in France and because I love it when my son’s class sings “Sur le pont d’Avignon”? Or maybe Mundo Verde because it’s 2014 and everybody needs to learn Spanish? Or—always back to this—why don’t I just keep him at his current school because we love it and it’s five blocks from our house?

• • •

A hundred and six days, the time between when the lottery opens and most matches get made this year, is a huge chunk of time to spend in a whorl of uncertainty. I say “most matches” because the truth is that the new unified lottery isn’t everything its designers hoped it could be. Some of the charters that declined to take part are among the most popular schools in the city. That means waiting lists will still be jammed. What’s more, some of the perverse practices of the old days persist.

Washington Yu Ying, the Mandarin-immersion school, still time-stamps applications, meaning the earlier you get yours in, the better your position on the waiting list. A father who’s dead-set on getting his kid in there, walked me through the panic-inducing process.

In 2012, when the school’s online lottery opened, he had three computers ready. But the site kept crashing. So this past fall he decided to go in person. “We drove by the night before around 10 to scope out the area, with plans to show up around 3 or 4 am,” he told me. “We found one person sleeping in front of the gate, so I decided to grab my winter jacket and head over. When I came back around 11 pm, five families had already started camping in front of me.”

By 3 am on that cold fall night, this father said, a line of more than 60 people snaked around the corner. “Even though I was wearing three pairs of socks, I couldn’t feel my feet by 6 am and I was concerned about frostbite. Some parents were better prepared with tents and camping gear, while people like myself just slept on the sidewalk. I spoke with a few parents and found out that everybody who’d arrived before 1 am had driven by to scope out the place, seen parents already camping, and quickly returned to spend the night.”

Around 7:30 that morning, 30 minutes before the school began accepting applications, the crowd found out that the first person in line—the one who started the panic—had been paid to camp out. WTF? Somebody hired a professional line-stander? (Booing ensued.)

Awful as it was, the dad doesn’t regret his all-nighter. “I was happy to leave with an 8:02 time stamp on my application,” he told me this winter. “I hope the camping-out pays off.”

• • •

For a voice of reason, some parents shell out for time with E.V. Downey, an educational consultant who has made an unexpected career out of advising families about their best public-school options—the only person in the country, she believes, with this job description. Downey does it all: private consultations, group seminars on the ins and outs of the lottery, and 45-minute “mini-sessions” for parents who’ve already done some of their own homework.

When she started her business 2½ years ago, she anticipated she’d be working primarily with private-school parents. But the vast majority of Downey’s one-on-one clients—175 out of approximately 200 this past year—are desperate for help with the public schools. “I provide a whole lot of empowerment,” she says. “I try not to make people feel bad about their options.” Most important, Downey says, she pushes research: “If you just put down those pie-in-the-sky schools, then more often than not you end up with nothing.”

Greg Fairbanks, a 40-year-old tax lawyer who lives in DC’s Bloomingdale, might be a model for all of us. When it came time for his eldest to enter the lottery five years ago, he straight-up dismissed the buzz factor that lures so many parents and instead performed what he called his own “statistical triage,” using three previous years of test scores to group schools into three acceptable categories: highest performers, higher performers, and improving performers. Next, he examined four years of publicly available online DCPS lottery results to figure out which schools were realistic and which would be wasted lottery slots.

If parents “just apply based upon school visits and warm fuzzies,” he told me via e-mail, “they are setting themselves up for failure. Suppose a parent decides he or she really likes the following five schools: Oyster, Stoddert, Eaton, Ross, and Murch”—mostly WOTP and extremely competitive. “They know Oyster and Murch are long shots but have not done any statistical analysis to understand what the odds really say. What if those schools’ percentage acceptance rates are, respectively, 5 percent, 2 percent, 10 percent, 10 percent, and 0 percent?”

A parent with that wish list, Fairbanks discovered, had a 75.4-percent chance of striking out. He didn’t like those odds for his child. He used his picks only on schools that he considered acceptable from an academic standpoint but not impossible from an admissions vantage and came up with “two ‘long shots,’ two ‘not so bad,’ and two ‘more likelies,’ ” he told me. Fairbanks calculated that he had at least an 85-percent chance of getting in somewhere.

He was right. His child nabbed a slot at one of the “more likelies” as well as a top-three waiting-list number at one of their long shots.

But here’s the kicker: His kid also got into LAMB, a popular charter that wasn’t required to furnish any previous-year admission information and thus didn’t factor into his number-crunching. So for all of Fairbanks’s hard work maximizing the chances of getting into a good DCPS school, none of it really mattered: In the end, his family chose a charter they got into the way most people have—by pure chance.

• • •

I guess that’s the part I find most maddening about this whole process.

For all my hemming and hawing over whether I really need to “win the lottery” to feel good about my son’s education, I don’t actually have any agency either way. Short of striking it rich and/or moving to the suburbs (or a suburban-feeling corner of Northwest DC), I can’t control where my son goes to school, the way I can choose what to serve my kids for dinner or which overpriced nontoxic shampoo to use on their hair.

It’s the illusion of choice that drives so many of us to our spreadsheets in a desperate scramble to beat the odds. But however you refine the process, the DC school lottery remains just that: a lottery.

“Want to come with me to the Mundo Verde Open House next weekend?” I recently e-mailed a friend who, after a poor showing last year, decided to keep her thee-year-old in daycare.

“Why bother?” she wrote back. “Honestly, at this point I am seriously considering keeping her where she is next year and moving to Northwest or Maryland for kindergarten.”

Laura Moser, who lives on Capitol Hill, is coauthor of four young-adult novels and a regular contributor to the Wall Street Journal. You can find her on Twitter @lcmoser. This article appears in the April 2014 issue of Washingtonian.