Ronald Goldfarb, a tanned, white-haired attorney with very black eyebrows and the self-assurance to tell the same jokes multiple times in front of the same person, published two books this year. One—a collection of essays he edited by various experts on Edward Snowden—would seem to be the one being feted last May at the Dupont Circle offices of the PR firm Levick, where an after-work crowd mingled over white wine in plastic cups and a sweaty grapes-and-cheddar plate. But the party was also celebrating the release of a very different book: Goldfarb’s romance novel, Courtship: A Novel of Life, Love, and the Law, published under the pen name RL Sommer.

Before making his remarks, Goldfarb, 82, traced the highlights of his distinguished career for me: writing speeches for Robert F. Kennedy, defending migrant farmworkers, and writing nonfiction. Then, about 15 years ago while resting from a tennis injury, he was inspired to pen a novel, spitting out a draft in a single month.

“I didn’t want to stop,” Goldfarb said. “It was almost a sensual pleasure.”

Getting a drink, I met Sarah Auchterlonie, then an assistant litigation deputy at the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. (She has since moved to Colorado.) Without much prompting, she told me she had recently completed the first draft of a romance adventure under the pseudonym SJ Maitland, “about a centuries-old fairy princess who’s looking for love throughout world history.” Auchterlonie had about 120,000 words, she said, all written on snow days, nights, and weekends since January.

As I wandered through Levick’s space-age events area, it was hard to find a lawyer who hadn’t taken a stab at fiction. While I was discussing favorite novels with Lanny Davis, the executive vice president at Levick more famous for being a damage-control operative for Bill and Hillary Clinton, his gaze grew a little sheepish. Davis went on for a bit about “the novel I’d love to write” before confessing he’d written an ample outline, based on his unsuccessful run for a Maryland congressional seat in 1976, about “the hard choices in politics between sticking to principle and doing what’s necessary to get elected.”

Many people in Washington would be tickled to see what Davis had to say on that topic, but he says: “I just didn’t have the courage to be rejected.”

• • •

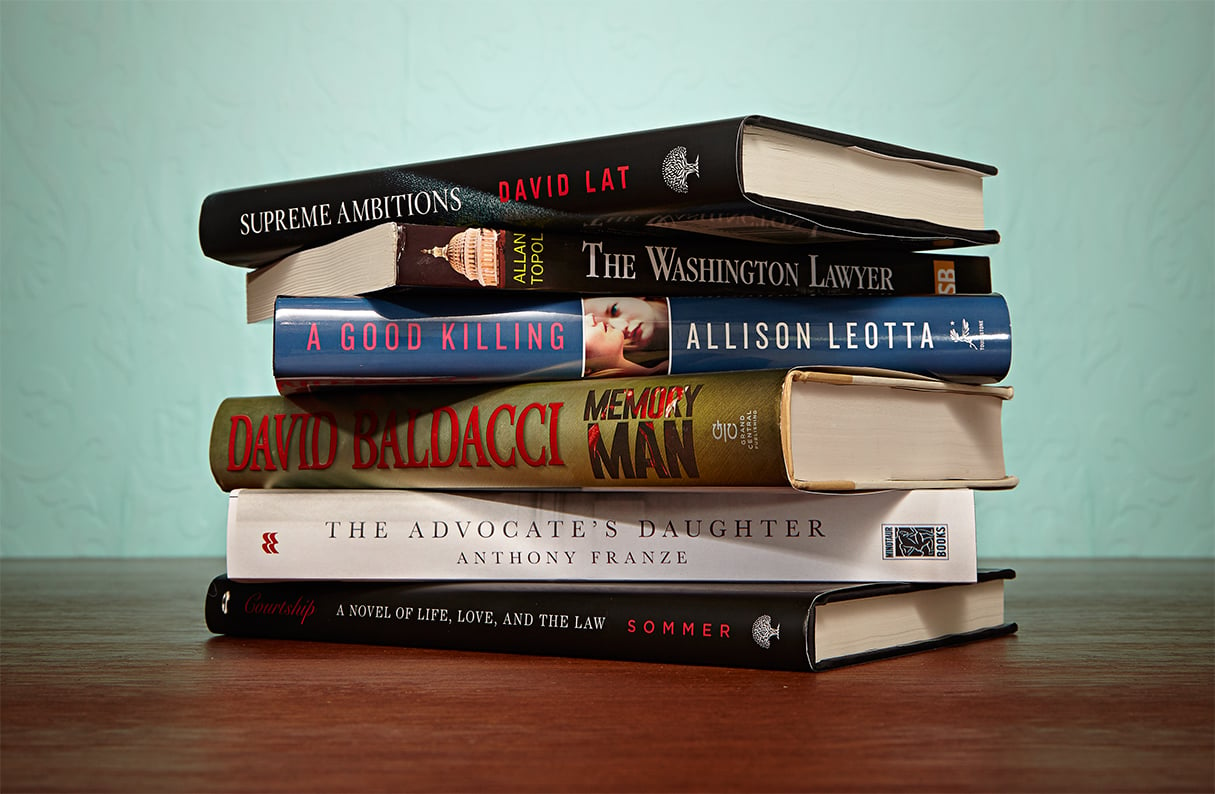

The good news for lawyer/novelists is that the hunger for legal lit is on the rise. Last December, the American Bar Association launched Ankerwycke, an imprint dedicated to law-related fiction and literary nonfiction. (According to legend, Ankerwycke is the name of an ancient yew tree near which the Magna Carta was signed.) Ankerwycke’s director, Jonathan Malysiak—who edited Goldfarb’s novel—says the enterprise has the advantage of the ABA’s hefty subscription list. (Ankerwycke’s first fiction offering, Supreme Ambitions by David Lat, a former attorney who founded the blog Above the Law, sold more than 5,000 copies in hardcover and about half that again in e-book—better than average for a debut novel.)

Malysiak is confident that Ankerwycke’s books will also appeal to a general audience. “There’s something sexy about having a story set in DC,” he says, noting the success of Netflix’s House of Cards and the flood of pitches he gets from Washington addresses for novels about “congressmen behaving badly.”

The promise of big sales, however, hardly explains the number of novels salted away inside mahogany desks. Attorneys have lucrative day jobs, and any writer, even a successful one, can tell you that the connection between writing and riches is tenuous. Über-lawyer/novelist David Baldacci, a former associate at Holland & Knight, wrote unsuccessfully for more than 15 years before striking it rich with Absolute Power in 1996. For much of that time, he wrote every night from 10 pm to 2 am, after a full day as a trial lawyer and evenings as a young parent.

Certainly, attorneys have the attributes of a novelist ground into them, billable hour by billable hour. They’re disciplined, practiced writers (all those briefs!) and are exposed constantly to human conflict. If the hardest part of telling a good story is knowing what to tell and what not to, legal minds are also adept at emphasizing certain facts over others. As Baldacci puts it: “I always say I wrote my best fiction as a lawyer.”

But ask lawyers why lawyers write novels and they’ll tell you it’s not the skill set—it’s the profession. Fiction, many say, is a much-needed antidote to the sheer tedium of the practice of law (all those briefs!). As Patrick Anderson, who reviews thrillers for the Washington Post, theorizes, “A lot of lawyers are very frustrated with being lawyers and see a lot of drama of various kinds and think, ‘Gee, I’d like to write a book about that.’ ”

This scenario overlooks the fact that not all lawyer lit focuses on gritty realities unveiled in court. Goldfarb’s novel tells the tale of Micah, a Chicago Jewish boy who grows up to be a public-interest lawyer handling some cases not so far off from Goldfarb’s own. Micah’s love is a Southern belle named Anne, described as “athletic, naturally and effortlessly bright.” Goldfarb assured me the book is not autobiographical. So did his wife of 58 years, Joanne, who said, smiling quietly, “I’m not a tall Southern belle.”

Anderson’s construct also fails to account for the fact that few lawyers I spoke to would trade their days jobs for the writer’s life. Literary lawyers are dreamers whose dreaminess is hardened by a law-review-prep work ethic—and not a little ego.

• • •

Allan Topol’s office at the Covington law firm, on the tenth floor of the new CityCenterDC building, is all milky-white glass paneling, sliding doors, and floor-to-ceiling windows overlooking downtown.

Topol has published 11 thrillers—including last spring’s The Washington Lawyer—while working full-time at Covington and helping raise four children. His website calls him a “national bestselling author,” and his books are noticed by Publishers Weekly and the Post. (The Washington Lawyer, Anderson wrote, “has its faults—occasional clunky dialogue and improbable events—but it moves along nicely.”)

Sitting in his antiseptic office, Topol—lanky and floppy-haired at age 74—says he turned to fiction because the newspaper op-eds he was writing about world affairs weren’t, he thought, enduring enough: “I wanted something that wouldn’t just wrap the fish the next day.”

He writes his novels longhand on legal pads during weekends, early mornings, vacations, and business trips. (“Airplanes are a great place to work.”) Indeed, now that he’s senior counsel at Covington, his books seem to grow out of an expanded availability for travel. The settings for his next one, The Italian Divide, are some of his favorite destinations. “Milano . . . Torino, Stresa—you’ve been to those places?” he asks me. “Oh, you’ve got to go. It’s like nothing else.”

Topol’s books are often inhabited by attorneys, and The Washington Lawyer is largely set at a big international firm on Pennsylvania Avenue that sounds a bit like Covington. (“They had offices in New York, Los Angeles, London, Paris, and Beijing,” the novel reads. “The firm was strong—almost an institution.”) But most are not legal thrillers per se—“I don’t do trials,” Topol says. “Washington lawyers will write novels about law firms: ‘This is terrible, this is awful.’ [But] this is not an awful institution.”

Never has Topol considered devoting himself to literature. His daughter asked him once if he’d ever thought about abandoning law: “I said, ‘Well, Daniella, if I’d have done that, you wouldn’t be here now, because we could only have afforded two children.’ ”

Finances don’t always keep lawyers in their office chairs. Anthony Franze, author of the Supreme Court thriller The Last Justice, works in the appellate and Supreme Court practice at Arnold & Porter. He writes late at night and on weekends, with a large box fan blocking out the noise of his family. Nonetheless, he says he loves what he’s doing in law and wouldn’t quit. What’s more, he notes, writing about murder in the Supreme Court demands a deep knowledge of that world.

As David Lat puts it, most lawyers “would not want to quit totally, because it gives them grist for the mill.”

• • •

Even those who do jump ship don’t go easily. Allison Leotta, who spent 12 years as a federal prosecutor, including eight in the DC Superior Court specializing in sex crimes and domestic violence, started writing about her experiences at the courthouse when she got pregnant, realizing that “my free time was about to become very scarce.” She woke up at 5 every morning to write for two hours. “It was the most disciplined thing I’ve ever done.”

After her first novel, Law of Attraction, was published in 2010 and she had a multi-book contract, Leotta left her job, but she calls it a “conservative” decision made reluctantly. She still calls up friends in law enforcement to make sure she’s getting details right. Recently, Leotta says, “I wanted to kill a guy in a car. So I called up a friend who was a detective in a major-crash unit. He understood I was not plotting to kill my husband.”

Leotta knew that to succeed at writing fiction, she’d have to be as strict with requirements and deadlines as she’d been as a lawyer. Baldacci, too, has thrown himself into fiction with lawyerly energy, churning out close to two thrillers a year and having a hand in his own contracts.

Listening to them, I realized that the reason so many lawyers write has nothing to do with the methodical, juggernaut tread of these consummate pros. Tossing off pulpy works of fiction allows the Topols and Goldfarbs and Leottas to envision themselves Renaissance men and women, like the humanist overachievers who, centuries ago, laid down the legal precedents they revere. Penning a novel on a yellow pad while flying back from an out-of-town client meeting is no compromise—it’s the ideal.

I thought of Sarah Auchterlonie, who pulled her 120,000-word fairy tale from countless hours of toil. “I would go down to the playroom in the winter and sit with my kids,” she told me. “They’d play Legos, and I would write for eight or nine hours a day.”

I asked her whether, if the book sold, she would quit being a lawyer. With an emphatic nod, she replied: “Totally.”

Contributing editor Britt Peterson (@brittkpeterson on Twitter) also writes about language and culture for the Boston Globe and the Atlantic.

This article appears in our November 2015 issue of Washingtonian.