Back in the ’80s, there was a television commercial for now-defunct Riggs Bank that made me want to punch the set. (Young ones, think: throw my phone.) After a montage of monuments, presidential helicopters, and other symbols of power, it closed by saying Riggs was “the most important bank in the most important city in the world,” thereby equating a GS-11 opening a checking account with sitting in the Oval Office.

For smug self-importance, it was hard to top, but it turns out the ad was a harbinger. Washington is increasingly a city built on public relations, advertising, and spin. K Street bristles with “communications” firms where would-be Don Drapers hawk energy bills instead of Lucky Strikes. Every assistant secretary has a speechwriter and an image-making entourage. If the president of the National Widget Association wants to influence the American Fairness Act of 2016—written by his people to place heavy tariffs on imported widgets—he hires a firm for advocacy, only a small part of which involves lobbyists glad-handing senators at Charlie Palmer. Most of the fee will be for placing ads in the Metro or on radio, or for putting widget-industry surrogates on TV to make the case for why backing widgets means backing America.

We’ve long needed an account of how Washington became Mad Men on the Potomac. A very good start is Republic of Spin by historian David Greenberg, who spent time as a researcher for Bob Woodward and as managing editor of the New Republic (where he and I worked together). Now a professor at Rutgers, Greenberg is no ivory-tower hermit. He has built his career bridging scholarship and journalism, writing regularly for Slate and now for Politico and focusing—as in his 2003 book, Nixon’s Shadow—on how presidential images endure.

His new volume, about how Presidents create spin, arrives just as voters are sizing up candidates for the office and meeting a new generation of Roves, Sorensens, and Gergens. The book is a reminder of a few important points: Spin has long been with us. Spin may be infuriating, but it’s rarely effective on its own. And it may not be so bad for us.

• • •

The use of rhetoric to sell ideas, warfare, or policies has been an essential part of governance since leaders wore togas instead of Brooks Brothers. Plato objected to rhetoric—spin’s name back then—as smooth-tongued oration that would inflame passions and distort the truth. (Most DC “crisis communication” firms might respond, “So what’s your point?”) The modern spin era began, Greenberg says, with Teddy Roosevelt. Until Roosevelt was thrust into office following the assassination of William McKinley, most reporters didn’t even cover the White House: After a half century of bland, bearded post-Lincoln chief executives, the center of power was Congress. Roosevelt made its new locus 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, pushing an ambitious agenda of trust-busting, government regulations, and military adventurism. For this, TR needed a PR strategy.

Roosevelt reinvented presidential addresses, in those days reserved for lengthy speechmaking in honor of national anniversaries, and turned them into almost daily news events. The presidential secretary, whose role had been expanded under McKinley to include the care and feeding of the press, now offered reporters informal sit-downs with TR, even while he was in his barber’s chair—and distributing wax-cylinder recordings of his speeches. The presidential tour around the country to bolster a political point was another Roosevelt innovation.

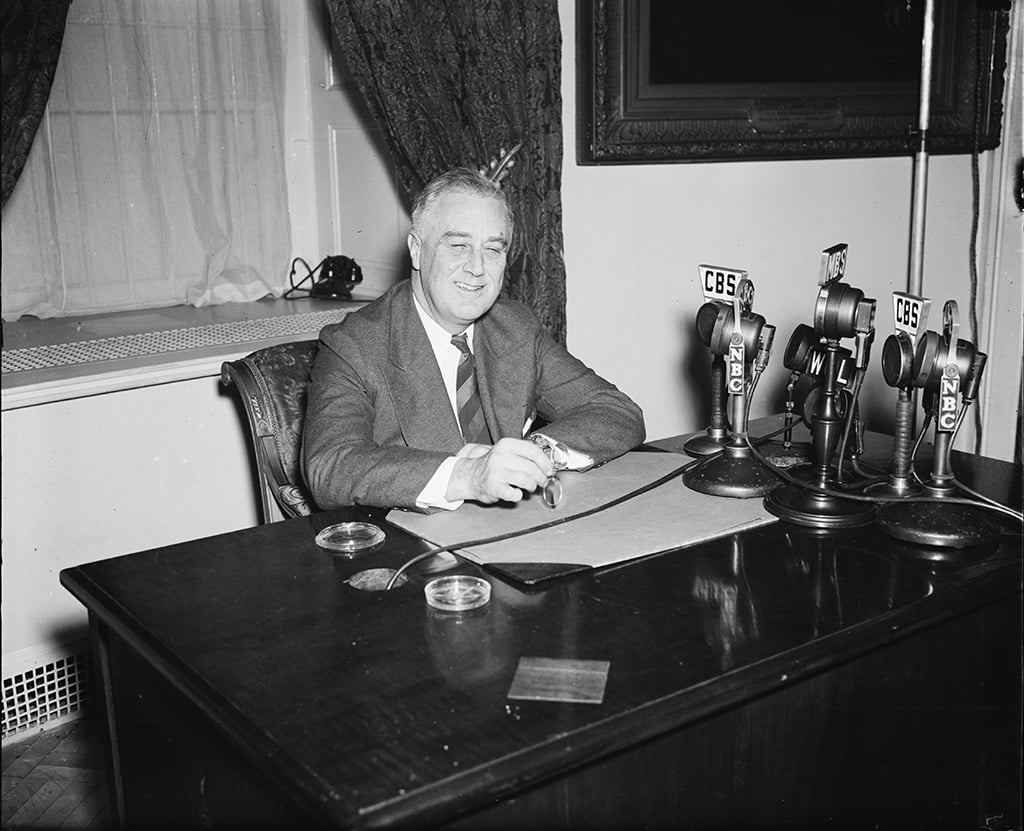

The role of spin grew in each subsequent White House. Speechwriters came on staff under Warren Harding. (Today the friendly fraternal organization of former White House speechwriters, including Washington monuments like Chris Matthews, is named for Harding’s ghostwriter, Judson Welliver.) Each President added his own twist on the culture of persuasion. Wilson was the first since Jefferson to deliver the State of the Union in person. FDR created a full-time press office and, in an era when most politicians shouted into a microphone like 19th-century orators in a town square, mastered the new intimacy of radio.

The rise of spellbinding dictators such as Hitler and Stalin raised fears about the sophistication of White House spin operations. Were Presidents becoming too adept at manipulating public opinion? The sense of alarm was apparent when Dwight Eisenhower made the first campaign television spot. His Democratic opponent, Adlai Stevenson—who spent 95 percent of his TV budget on 30-minute televised lectures—haughtily denounced Ike’s quickie ads. We know who won. A bestselling 1957 book, The Hidden Persuaders, portrayed the advertising business, political and otherwise, as a threat to democracy, expressing a fear that has persisted to our day.

• • •

Greenberg argues that facts will outweigh spin. A lousy administration can’t be saved by a good publicity machine. (As former Bill Clinton adviser Paul Begala put it, “The Titanic didn’t have a communications problem. It had an iceberg problem.”) Rather than acknowledge that their ideas failed, Greenberg notes, the losing side touts the victor’s ingenious communication skills. Democrats blamed their losses on Ronald Reagan’s practiced turns of phrase. Republicans convinced themselves that Clinton won two elections and survived impeachment because he was so slick.

The most famous example of he-won-because-he-was-silver-tongued may not even be true, Greenberg writes. We’re all taught that John F. Kennedy nailed the 1960 presidential debates because he was willing to use makeup and availed himself of now-basic TV techniques—such as looking straight at the camera when speaking. The proof is an oft-cited poll of radio listeners that found Nixon the winner, thus showing that television viewers were reacting mostly to JFK’s on-camera skills. Greenberg points out that the radio poll was too small to be considered accurate and makes a compelling case that Kennedy’s electoral edge came not from his image but from his arguments (or at least from Chicago mayor Richard Daley’s machine).

That’s not to say spin doesn’t have its place. Politics is storytelling, and each side needs to make its case. Depending on which one we’re on, we cheer FDR’s fireside chats or Reagan’s telegenic qualities.

Our K Street Don Drapers will enjoy hearing that they’re an enduring part of democracy—even if Greenberg jabs at their efficacy—and this essential book is going to wind up on every politico’s shelf. If I have a complaint about the massively researched volume, it’s that Greenberg didn’t include some of their voices—interviews with spin doctors might have leavened his documentary research.

The other missing element was out of Greenberg’s hands: the improbable rise of Donald Trump after the book went to press. Trump both confirms and refutes what Greenberg has laid out. Amid ever more sophisticated micro-targeting and brain research, the candidate has no polling team, no phalanx of speechwriters. He only recently started airing ads. There’s just the billionaire and his podium.

The combined weight of Trump’s id and ego will likely doom him. But with a dozen Republican opponents and Democrats waiting in the wings as well as armed legions of pollsters and super-PACs, one orange man has become the most interesting force in American politics through sheer instinct. Trump’s views may be abhorrent to many, but he’s making the Washington spin industry look utterly replaceable.

Matthew Cooper is political editor of Newsweek. This article appears in our February 2016 issue of Washingtonian.