It was a summer night in Amsterdam, and my 12-year-old son and I were trying to fall asleep in the hotel’s adjoining single beds. Our family had spent three weeks in Israel and the Netherlands, and this was the last night before our flight home to Washington.

“Dad?” Seth said.

“Yeah?”

“I hate time.”

“What do you mean?”

“I hate time,” he repeated, and I sensed not anger but an almost physical pain. “This whole trip—all the fun stuff—it just goes away, into the past. Why do we do it if time just takes it away?”

It was his and his sister’s first trip outside the US, and Seth was less taken by museums and landmarks than by little things: the tang of fried eggplant in an Iraqi-Israeli sabich sandwich, the water we splashed through in a pitch-dark aqueduct beneath Jerusalem, the miniature horses nibbling grass from his hands in his Dutch grandfather’s hometown.

I was ready for questions like “Can’t we stay longer?” But this felt different. Maybe all of life’s greatest moments, he seemed to be saying, were sparks that just sputtered, leaving an empty longing.

It had been a year of firsts for Seth. Not just the trip but the pituitary mutinies that were turning his friends gangly and deep-voiced and were coming for him, he was sure, any day now. Mornings found him practicing verses from the Book of Genesis—ones he’d soon chant on his bar mitzvah, the rite that tries to draw a hard line between boyhood and whatever comes next.

We returned from the Netherlands to a home that for Seth was shedding the familiar. His little sister, Phoebe, was displacing him from his childhood bedroom. She’d outgrown her room, and Seth had agreed to move to the basement. Before the trip, he’d crowed about having his own place, far from badgering parents and annoying sisters. Now that we were back, though, he said he wanted to stay in his old room a little longer: Phoebe could sleep on his bottom bunk—or even the top.

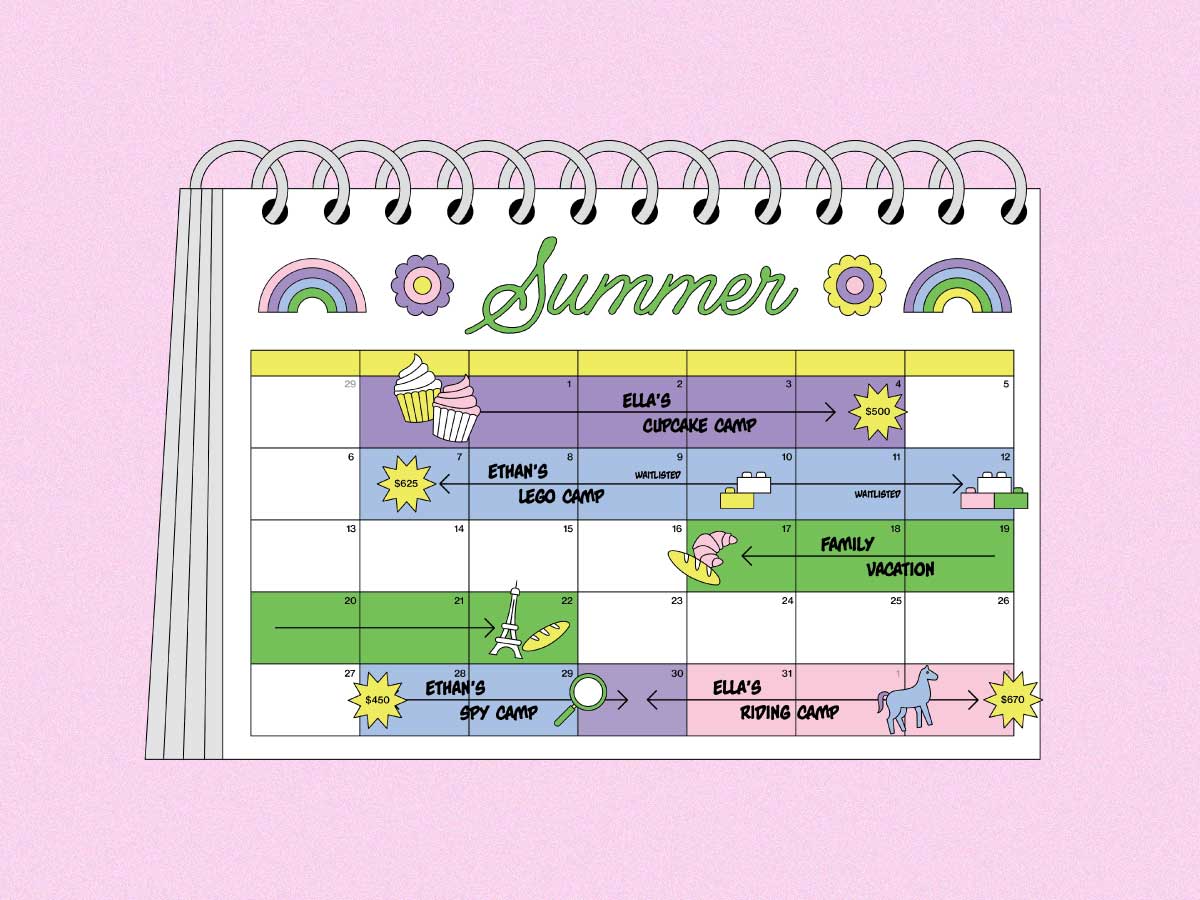

Phoebe liked this idea. She was four years younger, and he’d often kept her at arm’s length, insisting she ask permission before she so much as cast a shadow in his room. Now, though, he let her come and go, and he played with her like an equal. They’d get up early, read Captain Underpants, giggle. My wife and I let ourselves dream that something in their relationship had fundamentally changed. But the détente was a way station. Seth began packing for a month of camp—his first long separation from home. Then, a couple of days before the bus came, he asked if we could look at that basement room together.

“What do you think?” I asked as he studied its bare walls.

“Maybe some new paint,” he said. “Something brighter, so it’s not so lonely.”

On a paint store’s website he browsed the sunnier yellows.

That afternoon, as I cleared some last things from his old bedroom, I noticed faint indentations along the bunk’s railing. “Seth’s room from 6–12½,” he’d carved. “Phoebe’s room from 8–.” I finally understood. He’d spent half his life in that room, the part that takes a boy from kindergarten to seventh grade, tricycles to rollerblades, play dates to first dates. Something had closed for him, or nearly. But it was still open, for a time, to his sister. That’s what I’d failed to see that night in Amsterdam: Our vacation was ending, but so was a period of life—his, ours—that had once seemed without end.

I hate time, he’d said.

“Yes, Seth,” I wanted to tell him now. “I do, too.”

But he’d already moved on.

Contributing editor Ariel Sabar is the author of “My Father’s Paradise: A Son’s Search for His Jewish Past in Kurdish Iraq.” His website is arielsabar.com.