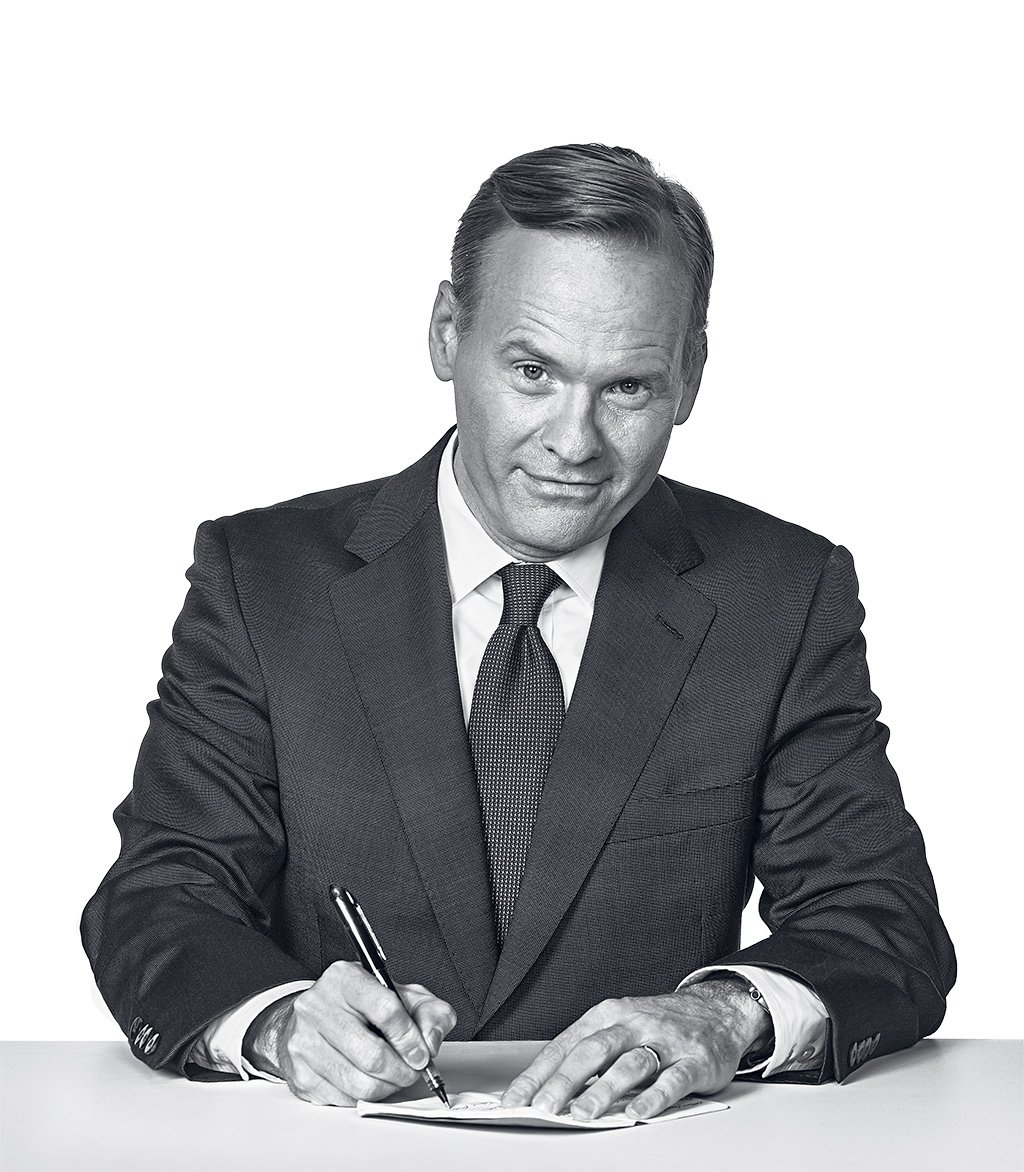

In a town that draws ambitious face-timers from all over the globe, John Dickerson is a rarity: a homegrown, and reluctant, celebrity. Raised in a 36-room McLean mansion by pioneering TV journalist Nancy Dickerson, the 48-year-old host of Face the Nation can vouch that the clichés of bipartisanship are more than nostalgia: Pols did once roam the city on weekends rubbing shoulders with journalists and members from across the aisle. “It was the water I was swimming in,” he says. “You weed the garden and you answer the door at these parties where Kissinger is seated here, Senator Frank Church is there, and Drew Pearson’s over there.”

Though he wrote in a 2006 memoir, On Her Trail, of his youthful rejection of that world, Dickerson followed his mother into journalism, working for Time for more than a decade before moving to Slate. Last year, he closed the circle when he joined his mother’s network, CBS, to replace Bob Schieffer in one of the media establishment’s key seats (he’s just the fourth Face the Nation host since President Reagan’s first term) and maintained the lead in the Sunday-show ratings war. We sat down with him to ask how the view from there is different, or unchanged, from the one he grew up with.

In your book, you wrote: “Covering Washington politics warps people. Covering it for a network can warp you even further.” What did you mean?

In my mother’s case, she couldn’t walk down the street without people stopping to tell her how wonderful she was. They would hold the plane for her. She could get dinner reservations when she wanted to. All of the abrasions of daily living are taken away from you. That doesn’t make for normal living at all.

You rebelled against that.

Yeah, I thought that basically what they did is they went to parties and talked about stupid things. It didn’t interest me.

So how do you go from there to becoming a political journalist?

Lord. Good question. In school I liked history and English, and in college I studied American history and literature—the story of America. And my mother would talk about the campaigns, which are great stories. I think that’s where we both kind of connected: trying to find out what’s going on and go tell people.

When you were approached by CBS to become an analyst eight years ago, you turned the job down. Was there still some resistance on your part?

I would have had to give up writing, which is the only way I know how to do anything. When CBS hired me for this job, they wanted me to keep reporting and writing, so the job has changed a little bit.

How did your mother influence the way you work now?

The biggest thing is she worked really hard. Because she was a woman, she operated in something a little closer to today’s social-media environment. Every time she went on the air, people who thought a woman didn’t belong there let her know that. She got letters to that effect, or critics would say, “What is this non-substantive person doing?” That’s what you get now when you read Twitter—trolls and getting flamed. She experienced that then in a way her male colleagues never did. So it’s her toughness and her hard-working diligence that I admire and try to emulate if I can.

What would you tell viewers from, say, Duluth who might look at John Dickerson—McLean upbringing, Sidwell Friends education, media-celebrity mother—and ask, “How does he connect to me?”

They would be right to be skeptical. But I try to make up for it in a couple of ways. I try to get on the road as much as possible. I spend as much time as I can in Wisconsin, where my mother was from. My wife is from Knoxville, Tennessee. I try and surround myself with wise people who have nothing to do with Washington. The benefit I have is having been out there for 25 years—all those notebooks are filled with conversations with voters.

What has that taught you?

You recognize that people are interested in the horserace, but interested in the way they like dessert—it’s not what they want all the time. The passion people have for politics is part of how they care about their country. They worry about their lives, their kids. All of the small ways people feel rooted in their communities are being stripped away, and they often look to Washington for some sense of stability, a sense that “I’m part of a country that’s doing good in the world and that has its act together.” Other people feel like the economic imbalances in this country are so glaring—how can people go to bed at night knowing their neighbor has three different jobs and still can’t pay for their kid to go to school? If you collect enough of those stories, they’re always with you.

It’s been about a year since you took over at Face the Nation. What has surprised you about the job?

It’s hard to answer that question without the first word being Trump. It was not a surprise that voters were angry or that Republican voters were angry at the establishment. Ted Cruz’s entire presidential campaign was founded on that idea. Scott Walker was going to do well, supposedly, because he was an outsider and had channeled the anger of voters into success in Wisconsin. Bush was not going to do well because his name smacked of insiders and the establishment. None of that was a surprise. There’s this weird idea going around, now that Trump has locked up the nomination—“Oh, they didn’t know about the anger in the country.” After the entire Tea Party movement, the entire off-year election? It’s just bonkers.

So what’s surprising—having spent so much time talking to Tea Party voters and voters who didn’t like Washington—is that the thing they didn’t like the most was politicians who changed their minds. They didn’t like candidates who constantly flip-flopped on the issues and just seemed never to be giving you the straight story. That those voters would put all their hopes and dreams in Donald Trump—who had changed his mind sometimes in the same interview—is surprising.

You’ve described your interview style as being a windowpane. What does that mean?

The idea is to use your questions so viewers can see the interview subject and not be distracted by a lot of me being fancy or me being Columbo or me being Perry Mason.

Does that approach work with a guy like Trump?

Well, no, it doesn’t. He’s a different case. When he was on Face the Nation, he tried to distance himself from the open violence at his rallies, and I had to say, “No, you said this, and a supporter cold-cocked a guy who wasn’t doing anything to him.” Trump just leapt over [the issue]. So then the question is do you take a third beat and say, “You just told an untruth”? Or does everybody get it? Once you’ve shown the video, they presumably get it.

So does classic journalistic evenhandedness serve the current situation? Or does this campaign require more activism?

Everybody is trying to figure out what that new level of activism is—and what being fair means. Certainly it doesn’t mean just giving him a platform to convey his views. It does require more, but there’s a balance. You ask tough questions, but then you have to give him a chance to speak. There’s a mix that you have to get right.

So how do you rate the way the media’s been handling it so far?

It’s hard to say. There’s been no shortage of fact-checking. Anybody with the negatives he has—with women voters, with Hispanic voters, with some young voters—the normal response would be “Boy, the media’s been so tough on him.” The other [critique] is: “The media did nothing, and that’s why he won the nomination.” I think it’s obviously something in between.

What’s your strategy for interviewing him?

I don’t have a grand unified theory yet. You ask questions that illuminate his thinking. You try to get him on the record and ask about inconsistencies in what he’s already said. Then you try to illuminate those larger questions in the hopes that he’ll say something that gives you a window into his thinking. This has been a different candidate than we’ve ever covered before. It may take a little thinking to figure it out.

Senior writer Luke Mullins can be reached at lmullins@washingtonian.com. On Twitter, he’s @lmullinsdc.

This article appears in our July 2016 issue of Washingtonian.

Note: As of June 2, 2016, John Dickerson has interviewed Trump 18 times.

![Luke 008[2]-1 - Washingtonian](https://www.washingtonian.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Luke-0082-1-e1509126354184.jpg)