As Congressional Cemetery president Paul Williams sifted through old interment records to find interesting causes of death among the 65,000 people buried there, one from 1899 caught his eye: “death by tiger bite,” it read.

Williams was baffled. A tiger attack in DC? Using the unfortunate man’s name, Charles Siegert, Williams did some research and found newspaper stories from the time describing what happened. After running away from home in Indiana to join the traveling circus, 21-year-old Siegert developed a strange habit of sleeping on top of the tiger cages in between shows. One night in September, Siegert’s leg slipped down the side of the cage as he slept, and before he knew it, Old Ben the Bengal tiger was gnawing at his leg.

“His cries awakened the whole tent and while men ran to his assistance the other animals roared and growled at the uproar,” the Washington Post reported at the time.

That night, after an emergency surgery to amputate his leg, Siegert died—just 11 weeks after he’d joined the circus. Seeing the story, a DC insurance man named Robert Cook offered to pay for Siegert’s burial at the Congressional Cemetery out of pity. But he didn’t pay for a headstone, so Siegert’s grave has been completely unmarked for the past 117 years.

Thanks to Guy Palace, a self-described circus enthusiast, that might finally change. Three years ago, when Palace and his wife were walking their dog through the cemetery, Williams told them Siegert’s story. Palace, 51, immediately volunteered to raise money for a proper headstone to honor Siegert’s memory. “It was a calling,” he says. “This was a project I could not help but (I hate to put it this way) sink my teeth into.”

Palace has been obsessed with the circus every since seeing his first Ringling Bros. show at Madison Square Garden when he was 11. He was blown away by the size and beauty of the animals, especially the tiger, and the experience has stayed with him his entire life. At American University, he wrote his masters in arts management thesis on the history of marketing in the circus, which he published as a book. He also worked for the Big Apple Circus for a short time as the props buyer.

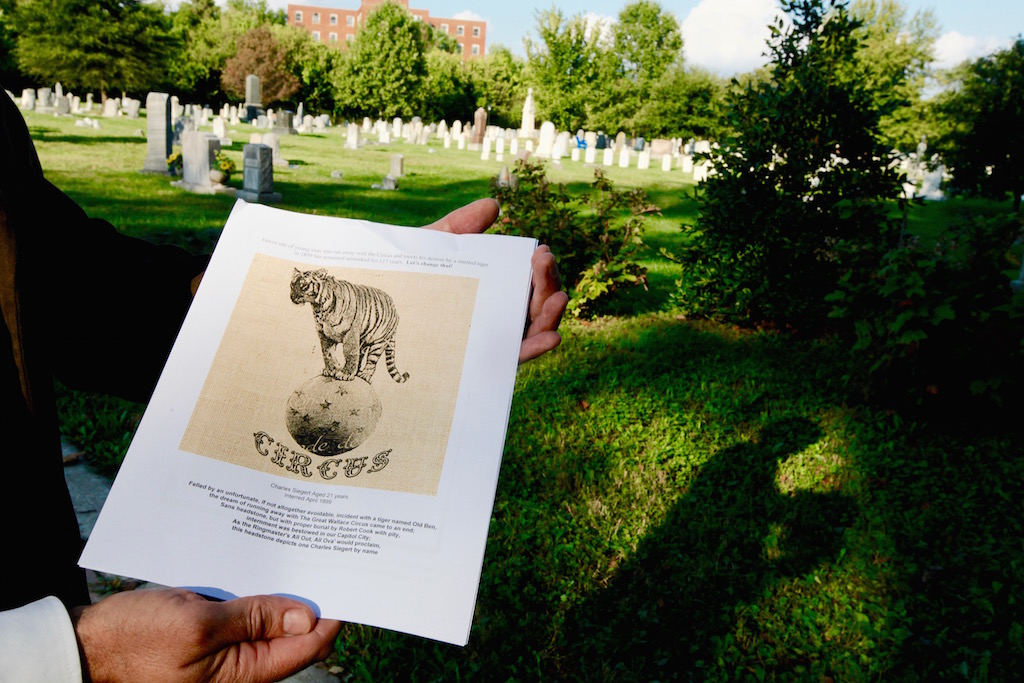

After a failed Kickstarter campaign to raise money for Siegert’s headstone in 2013, Palace is now trying again through GoFundMe. Since August, he’s raised $495 of his $2,000 goal. He wrote a poem and designed a graphic that he wants etched on the headstone. The poem goes like this:

Felled by an unfortunate, if not altogether avoidable, incident with a tiger named Old Ben,

the dream of running away with The Great Wallace Circus came to an end;

Sans headstone, but with proper burial by Robert Cook with pity,

interment was bestowed in our Capitol City;

As the Ringmaster’s All Out, All Ova’ would proclaim,

this headstone depicts one Charles Siegert by name.

“Those of us that love cemeteries, we glean a lot of their history of individuals from their headstones,” Williams says. “You’re discovering a soul for the first time who is going to be forgotten or probably already is.”

Palace isn’t the first person to campaign for a headstone to retroactively honor the dead. A few years ago, the former Congressional Cemetery office manager took an interest in Mary Fuller, a famous silent film actress in the early 1900s. She played Frankenstein’s bride in the very first film version of Frankenstein. Later in life, Fuller suffered a nervous breakdown following a failed affair with a married opera singer and was admitted to St. Elizabeths, where she died in the 1970s.

After raising enough money, the office manager commissioned a pink granite headstone with the Hollywood hall of fame star.

Shortly after that, a Congressional Cemetery board member was so intrigued by the story of Nicolas Dunaev, a Russian actor and circus performer who could bend a dime with his fingers, that she purchased his headstone herself. A historian from Colorado marked the grave of Charles Preuss, a cartographer who accompanied explorer John Fremont on his expeditions of the American West in the mid-19th-century.

Williams and his staff support these campaigns not only for their role in historic preservation but also because they remind the public that people buried there come from all walks of life. “You don’t have to be rich and famous or a congressman,” Williams says. “You just have to be dead.”

He also says that the cemetery isn’t just about remembering the dead; it’s about celebrating their lives.

If you’d like to donate to Palace’s GoFundMe, he plans on keeping it open until the end of October, with a possible headstone installation in November.