By any normal, democratic measure, Hillary Clinton should be the next president of the United States.

She didn’t just win the election by a little, she won it by more than 2.5 million votes (and her vote total is still rising). That’s not even a close contest.

If winning an election by millions of votes doesn’t make you the winner, what’s the point of even having an election?

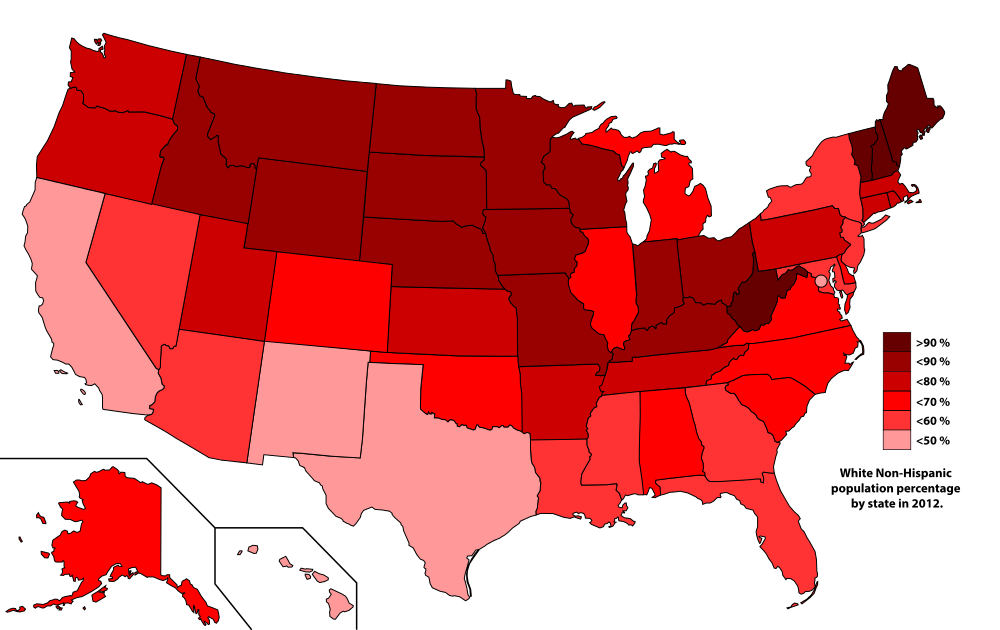

White voters are literally worth more under the Electoral College, due to the way US population is distributed. This quirk was not the intention of the Electoral College when it was created (although most states only allowed white, land-owning men to vote), but it is what the Electoral College means in 2016. America’s becoming more diverse, but that diversity isn’t evenly distributed.

The states with the highest relative weighting in the Electoral College are generally less diverse than the country as a whole. Wyoming is 92 percent white, while California is 42 percent white. A vote in Wyoming is worth almost four times more than a vote in California because of the Electoral College. Unless states like Wyoming suddenly become much more diverse, and more minorities want to live in them, the Electoral College will favor white voters.

A Hispanic vote is worth just 91 percent of a white vote. How is this possible? About 47 percent of Hispanic voters in the US live in either California or Texas. About 32 percent of Asian Americans live in California, and this is a core reason an Asian-American vote is worth 98 percent of a white vote. A black vote is worth 95 percent of a white vote, and this is before addressing historic voter suppression aimed at black people.

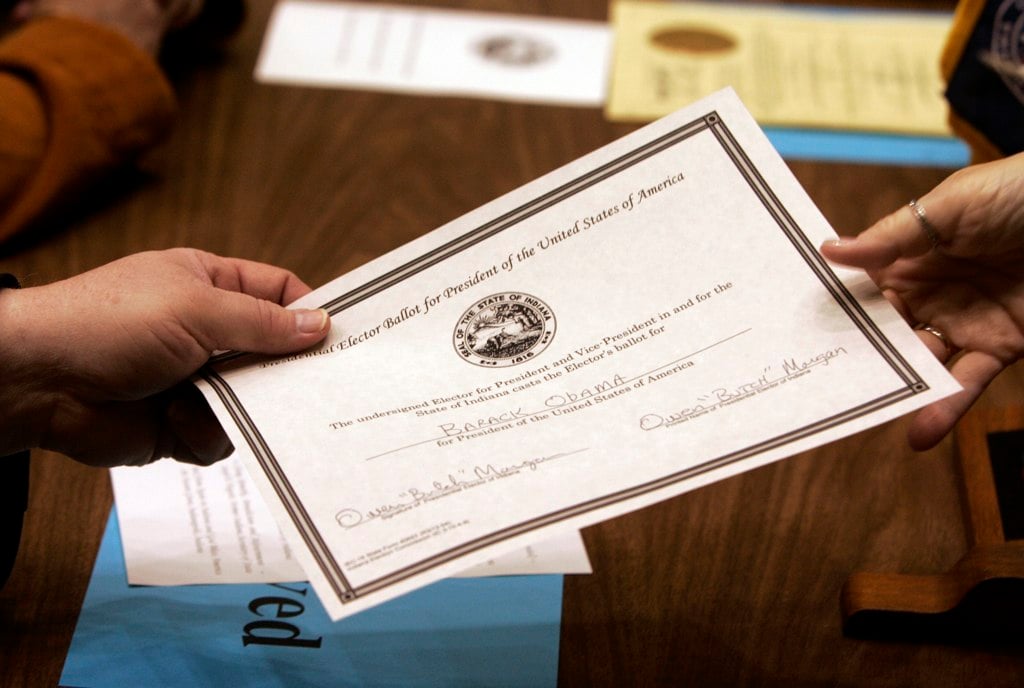

Because every state automatically gets two electors, commensurate with its number of senators, and the House of Representatives is capped at 435 members, electoral votes represent different amounts of voters across states. The Electoral College is not remotely proportional. Each of Wyoming’s electoral votes represents about 149,000 voters, while in Texas each electoral vote represents about 533,000 voters.

While the US as a whole is about 63 percent white, many states are less diverse. Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin, which decided the 2016 election, are all between 80 and 89 percent white.

My home state of Ohio is 85 percent white, but the county I grew up in was 97 percent white, and it’s not even close to the whitest county in Ohio. Monroe County, which has about 150 non-white people out of about 15,000 total, went to Donald Trump by about 80 percent.

Why are white, rural votes worth so much more than suburban and urban votes? Things have changed a lot since 1788, when the Constitution was ratified and the country’s population was distributed mostly among relatively small towns or rural areas. There are a lot of different arguments as to why we ultimately ended up with the Electoral College, from guarding against mob rule (i.e., common people voting) to protecting rural interests to getting slave states to ratify the Constitution (slave populations counted towards the Electoral College and helped smaller slave states make their concerns heard).

Two of those arguments are objectively offensive and one, protecting rural interests, is already covered by the Senate.

The Electoral College enshrines the protection of rural interests in the highest office of the land. Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania are big states, but it was the more rural, whiter areas that carried Trump to victory in those states. Romney won Pike County, Ohio—which is 97 percent white—by a single vote in 2012, and Trump won it 65-35 in 2016.

Under the winner-take-all mentality of the Electoral College, Ohio may have a population that is 15 percent non-white, but almost only white votes truly counted. This is the second way that the Electoral College protects white votes.

Much of the deep South is more diverse than the whole country. Mississippi is 57 percent white (it went 58 percent to Trump), but when white voters overwhelmingly vote for one party, under the Electoral College that state’s diversity is not presented in the final election results.

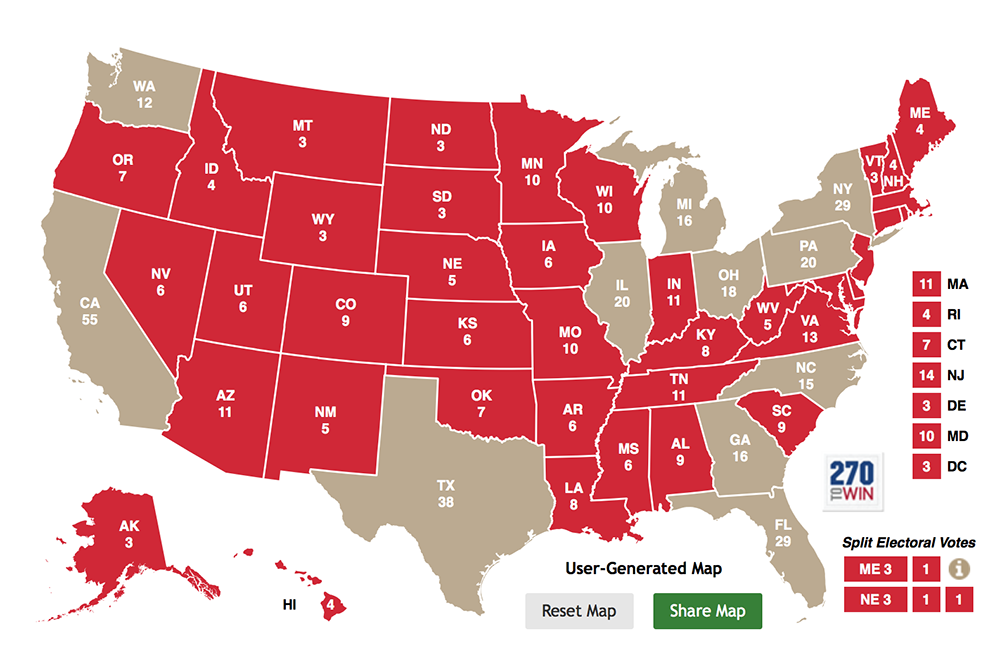

Trump did really well in the smaller, more rural states. He won Montana and Kansas by about 20 percentage points each.

In fact, by avoiding big diverse states, a candidate could win the US presidency with just 23 percent of the popular vote. All that candidate would have to do is appeal to the concerns of those who feel they have the least to gain from a diverse America.

Enter Donald Trump. His campaign sang the praises of an America of (whiter) years gone by. Voters who scored high on a survey for racial resentment heavily favored him.

Without the Electoral College, Trump’s racial gambit would not have worked–and it’s entirely possible he would have had to run a completely different, more inclusive campaign. Everyone’s vote would count the same, and getting razor-thin margins in white Midwestern states by appealing to some voters’ racial resentment wouldn’t matter that much in the grand scheme of the election.

Most people on the coasts are decidedly not elite. They are everyday people just trying to get educations for their kids and make ends meet. These are the voters that the Electoral College disadvantages the most. But since these non-elite voters–a barbershop owner in Baltimore or a line cook in the Bronx–aren’t white, rural voters, their votes don’t need to be pursued, much less cherished.

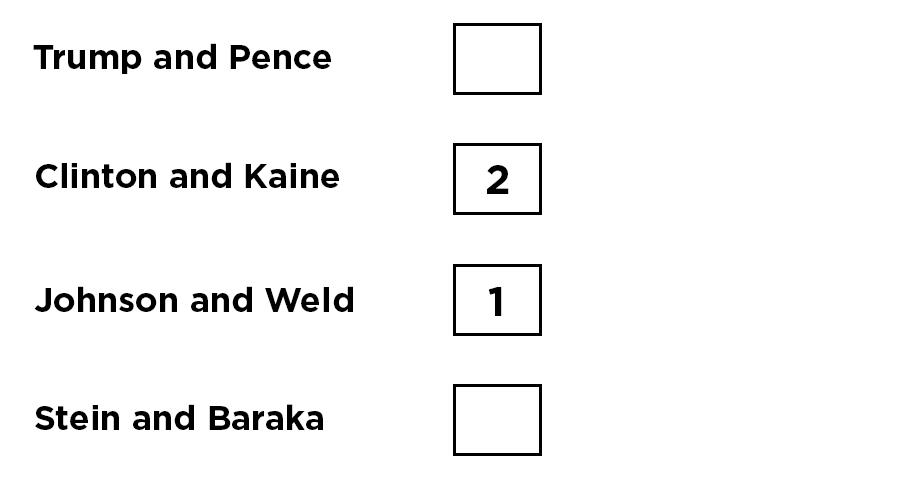

The only way to count all votes equally is to switch to the popular vote. But even that would offer one big drawback: It could allow a candidate to win the presidency without anywhere near a majority. One thing the Electoral College does well is discourage people from voting for third parties and splitting the vote too many ways. There are two ways around that: runoff elections or ranked voting.

A runoff election would pit the top two vote-getting candidates against each other if no one received 50 percent of the popular vote in the first round of voting. In 2016, this would have allowed Gary Johnson and Jill Stein voters to vote again and decide between Trump and Clinton. America already has relatively low voter turnout, and people often wait in long lines to vote. Asking them to potentially vote twice would probably be a very tall order (although the runoff vote would probably be incredibly exciting, so maybe I’m wrong).

It’s possible, though, that advances in voting technology will eventually obviate this problem—people may one day be able to cast their votes securely from a smartphone or home computer. But let’s live in 2016. So how about ranked voting? It’s kind of an instant runoff.

Under ranked voting, a voter could list Jill Stein as her top choice and Hillary Clinton as her second choice. If Jill Stein was not one of the top two vote-getters, her votes would be reassigned to the candidate that voters ranked No. 2 on their ballots.

If the November 8 election had been carried out in that system, most of Johnson, Stein and Evan McMullin’s votes would have been eventually cast for either Trump or Clinton, and we would have a winner based on the democratic will of the people and someone who had a mandate with more than 50 percent of the vote. Ranked voting could also empower third-party candidates. You wouldn’t feel like you were throwing your vote away if you could fall back to a second choice.

But just because the road is long and winding with an unknown end, doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t consider that journey. If this situation is not fixed, and demographic trends with an increasingly diverse population in certain states hold up, white votes will not only be worth more than black, Hispanic, or Asian votes, but their vote power may increase even more.

The question Americans will have to ask themselves is: Is that the kind of country we want?