Women have been worrying about what will happen to their access to contraceptives without cost sharing since Donald Trump was voted into office. The morning after the election, a flurry of blogs were published about why women needed to rush out for an IUD, ASAP.

The Affordable Care Act required that insurance companies provide women with access to preventive services—which, by the way, includes everything from mammograms to breastfeeding counseling, along with birth control—with no cost-sharing. Under the ACA, copay-free birth control made it possible for women to avoid paying up to $60 a month for the Pill (which I did in a pre-ACA life) or hundreds of dollars for an IUD.

According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, since 2012 there’s been a drop in what we’ve spent on retail drugs—and 63 percent of it is attributed to oral contraceptive pills. This means that Pill counts for more than half of all the money we haven’t been spending on drugs since the ACA was established.

The Senate has already started making moves to repeal the ACA, making the threat on no-cost-sharing birth control very real. But while some oral contraception retails for $60 a month and some IUDs can retail for over $1,000, what might women actually spend out of pocket on contraception in a post-ACA world?

What were we spending before?

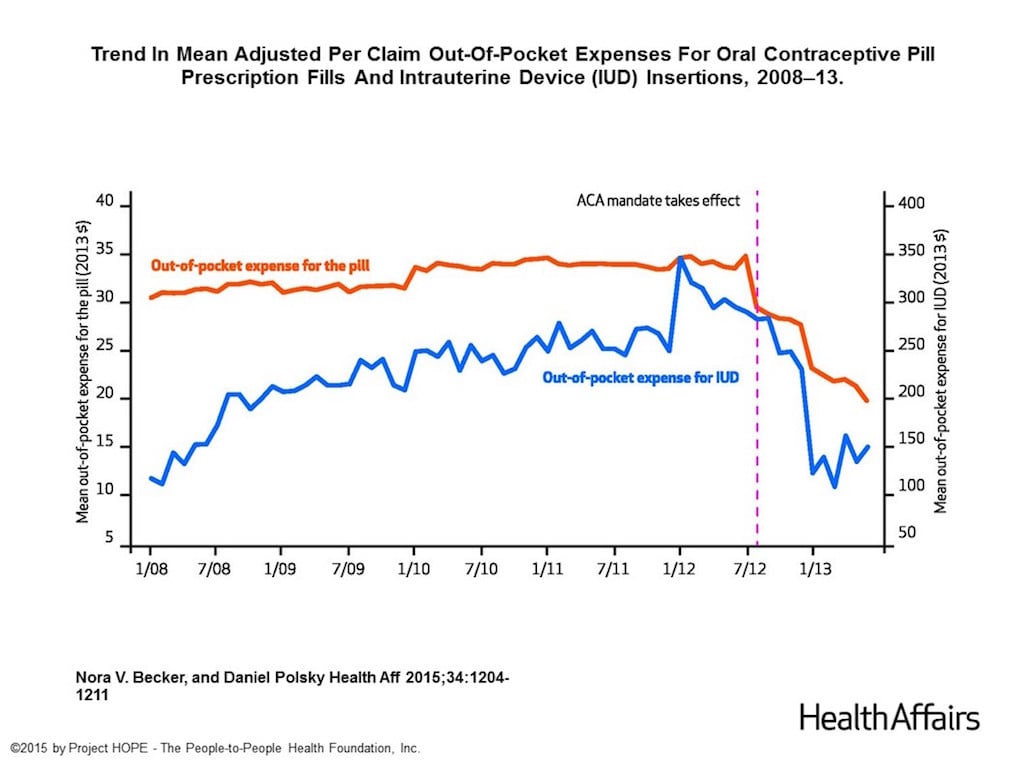

It’s helpful to look at what women were spending out of pocket before the ACA came into place. A study published by Health Affairs looks into just that. Authored by Nora Becker, who not only has a PhD in economics but is also working towards her MD at the University of Pennsylvania, the study used data from a major national private health care provider to examine the out-of-pocket expenses for birth control for 790,895 reproductive-age women.

Of course, the study only looked at one health care company. But by examining the out-of-pocket expenses incurred between 2008 and 2013, Becker found that the women spent on average $248 more for an IUD and on average $255 more annually for oral contraceptive pills before the ACA went into effect.

“I took a random sample of reproductive-aged women, and I looked at what they paid for their birth control, if they got it,” says Becker. “What I saw was pretty unambiguously that the [ACA] had significantly dropped that amount, whether you look at it in averages or in medians or anyway you sliced it.”

While one might expect that women with health insurance would be paying nothing for birth control while under the ACA, what Becker found was that while the out-of-pocket amount was significantly reduced, some women were still paying. According to her findings, in June 2013 women were paying on average $19.84 for a prescription of the Pill and $145.24 for an IUD insertion.

Though the ACA required no cost-sharing, Becker says that her study group included some women who were on plans that had been grandfathered in, while other women were used a particular brand of contraception that may have not been covered by their insurance. Nonetheless, though not all women in the study were instantly paying nothing for their contraception, Becker says by 2013 there were significant decreases in how much they paid out-of-pocket for birth control.

What will we spend now?

The real question is: If the ACA is repealed, should women expect to pay on average $255 more per year for the Pill? According to Becker, it’s impossible to say.

“I don’t think anyone can really answer that question for sure, and this is the reason: If you remove the mandate, then insurers can price things how they want to again, and there’s no rule that says that insurers have to go back to the way the cost sharing was for these products before the law went into effect,” she says. “Basically, what I can say is, when it comes to regular women who are in private insurance, there’s no guarantee that the costs will continue to be zero, and I think there’s a decent chance that it wouldn’t continue to be zero.”

Though it’s impossible to predict exactly how the removal of the ACA could increase out-of-pocket expenses for women seeking contraceptives, Becker’s study at least helps to give a frame of reference for what women were spending without the ACA. Given time, Becker says she hopes to look into how access to cost-sharing-free birth control has increased its use, and from there, if that has decreased unplanned pregnancy and abortion rates.

“There is literature not looking at this particular law but the legalization of the Pill back in the ’60s and ’70s, and that literature has shown that women who had access to the Pill, compared with women who did not, had better financial outcomes, better educational outcomes, and that their children actually had better educational and financial outcomes,” says Becker. “I think there’s strong evidence in the literature in general to say that access to reproductive healthcare makes women and their families better off, and I think that can and should be a goal of our healthcare system.”