Honestly, you might not even need to read the rest of this piece. You might already understand that headlines have become the main event in modern journalism, that they are the only thing that most people will ever experience in a story.

But perhaps you are a journalist concerned about the next president’s freedom of the press, or his personal attacks on journalists, or the vast distance between many of his public statements and the truth. All valid concerns, and you might even be working on an article about them. Stop. Take a little advice from someone who understands, perhaps better than anyone you know, how information moves nowadays:

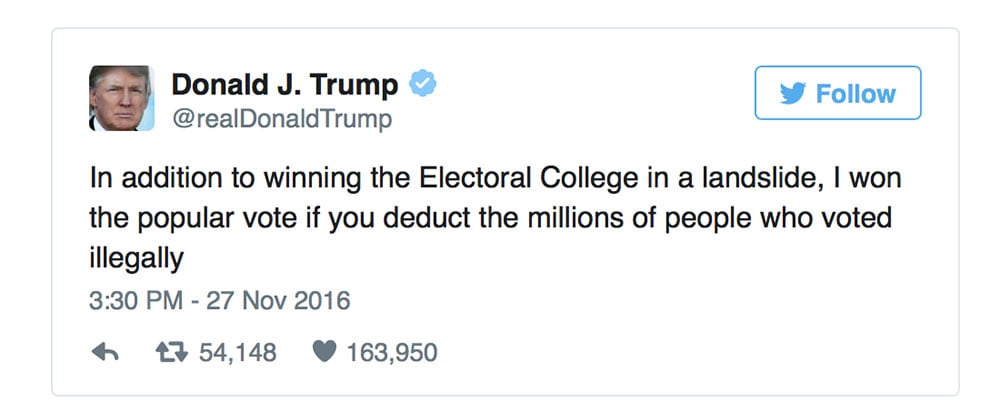

Here is a bald-faced lie from the next president of the United States. What would be the most important element of your report on this statement? Your research into how voter fraud is very rare in the United States? Your interview with state election officials? Your collection of other false statements Trump has made on this subject?

The most important part of your story on Trump’s lie is, in fact, your headline. If your headline reports the claim, and doesn’t note it’s false, that it isn’t based on a shred of evidence, it would deliberately misinform the public, no matter what you wrote beneath it. Why? Because for a lot of your audience now, the headline is the story.

72 percent of Americans get news on smartphones, where they discover stories via news alerts (most recipients don’t click through to stories) and social media. Most users catch glimpses of headlines on Facebook and Twitter. Sometimes they click through to read the story, but many times they do not.

Journalists must craft headlines that live with the reality of how people actually consume news online. Our job as journalists is not to wish that people slowed down and read every word we write; our job is to deliver information to people in ways that they’ll actually consume and internalize it.

In the Trump era, this won’t work anymore. Trump routinely says or tweets out something that is factually incorrect. If journalists write a standard headline of “Trump: Factually incorrect statement” and expect readers to read the story to find out that what he said is factually incorrect, they are misleading readers and helping to spread misinformation.

This USA Today headline textbook example of how journalists and news organizations are used to handling statements from politicians and public figures. The first sentence of their story immediately clarifies that what Trump said is an “unsubstantiated claim.” The problem is, most people will never read that far.

The volume, magnitude and audaciousness of Trump’s lies are something that journalists are struggling to adapt to. A big part of this issue is that many journalists and news outlets still think of headlines as something you work on after you write. The usual process is that a journalist will gather facts, interview people and write a story. At the very end she, or someone else, will tack on a headline. The headline will usually deliberately not restate anything that’s in the opening sentence or paragraph of a news story. The headline may also leave out crucial details, because writers and editors assume people will click through and actually read.

Here are some quick recommendations for writers:

- Think of the headline when you begin writing a story, when possible. Once your reporting and research is completed, you should know the direction of your story. Now is the time to craft that headline. If you are going to write a story about something a politician has said or done, you can write the headline first and let it set the tone for your piece

- If you have to write a news headline after a piece is completed, make sure the headline is informative enough to tell a story in a tweet. If your headline requires a reader to click through from social media, your headline is not good enough.

- Before publishing, always ask this: Could a reader be deceived by this headline if they never read the story?

Here is how the process usually works for me at Washingtonian. Editors maintain final say over the headlines, and they care a great deal about them, but all of my story pitches need to come with a proposed headline. If I can’t pitch at good headline, maybe I don’t have a good story.

Different news outlets are handling Trump’s lies differently. Some are repeating them verbatim, which serves to only mislead readers. Others are gingerly dancing around the subject of how to correct a president-elect who is deliberately spreading FUD (fear, uncertainty and doubt).

The core problem with this headline is that it suggests the problem with Trump’s claim is a lack of attribution, that evidence could be found. But there is no evidence that millions of people voted illegally, and any claim that Trump won the popular vote when you get rid of illegal votes is a lie.

Here is the Washington Post handling this situation properly.

That headline tells the complete story. If you want to go more in depth about this, you can read the story, but if you just read that headline, you would not be uninformed. Journalists need their own hippocratic oath that also focuses on doing no harm. Headlines that mislead or allow false information to be spread do harm.

Our jobs are to share the truth and help make a more informed and educated world. Our jobs are not be combative with politicians and public figures, but we must choose our language carefully so that we don’t contribute to misinformation being spread.

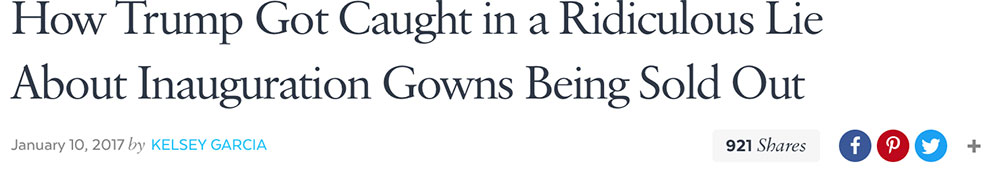

Trump is willing to stretch the truth and lie about the most banal of things. There is a real risk that readers and journalists will grow tired of calling these out.

On the other hand, here is an excellent example from Diana Pearl about how you can call out a untruth with different language.

There may be merit in journalists having restraint in which stories they write based on his tweets. Will the public get tired of hearing that Trump lies or that he stretches the truth? Will these admonishments start to lose their impact?

Maybe, but we always must make sure our headlines tell an accurate story.

Here is a small sampling of the statements from president-elect Trump that Politifact ruled “pants on fire” (a level beyond “false”):

- “We don’t have any” chess grandmasters in the United States.

- There was serious voter fraud in Virginia

- Says a tweet he sent out “wasn’t saying, ‘check out a sex tape.’ It was just ‘take a look at” the background of Alicia Machado.

- There was serious voter fraud in New Hampshire

- Donald Trump’s Pants on Fire claim that millions of illegal votes cost him popular vote victory

- Says that at a campaign rally President Barack Obama “spent so much time screaming at a protester, and frankly it was a disgrace.”

- “Inner-city crime is reaching record levels.”

- Says Ted Cruz “never denied” his father was photographed with Lee Harvey Oswald.

- Says Barack Obama “founded ISIS. I would say the co-founder would be crooked Hillary Clinton.”

- When Hillary Clinton “ran the State Department, $6 billion was missing. How do you miss $6 billion? You ran the State Department, $6 billion was either stolen — they don’t know.”

- Says crime statistics show blacks kill 81 percent of white homicide victims.

As you can see from Politifact, there are a lot of lies to track from President-elect Trump. It’s willing to call out every lie from the most serious to the most banal (the US doesn’t have chess masters?). It also does a good job of finding different ways to point out these untruths without using the same language over and over again. That’s a skill we’re all going to need to develop.