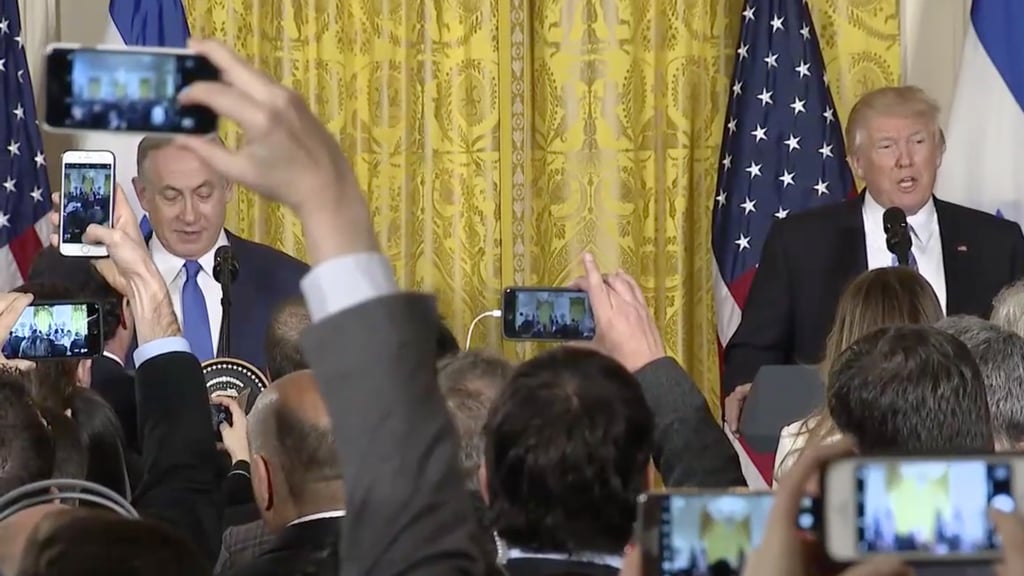

During a joint press conference Wednesday with Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, President Trump continued his White House’s streak of taking more questions from reporters affiliated with conservative-leaning organizations than legacy networks and publications. The first and third questions came from Christian Broadcasting Network’s David Brody and Townhall.com’s Katie Pavlich, while reporters from outlets like ABC News and CNN were left to shout in vain as Trump and Netanyahu left the podium.

And on Twitter, what has become a near-daily freakout about the White House’s question-picking strategy broke out anew.

Trump has so far called on Christian Broadcasting Network and Townhall—he's only called on conservative outlets for last three pressers.

— Kyle Griffin (@kylegriffin1) February 15, 2017

The two outlets called on today in Trump's presser: Christian Broadcasting Network, and a conservative blog.

— Michelle Kosinski (@MichLKosinski) February 15, 2017

Trump has called on ONLY conservative outlets in his last 3 joint press conferences.

— Chris Cillizza (@ChrisCillizza) February 15, 2017

To be clear to viewers around the world, in the last 3 press conferences, Trump has ONLY called on conservative news outlets for questions

— Katty Kay (@KattyKay_) February 15, 2017

It’s become a regular midday exercise on social media to complain that Trump and his press secretary, Sean Spicer, prefer to call on media organizations perceived as being friendly toward the Administration instead of, say, the Associated Press, which until recently enjoyed a tradition of asking the first question at White House briefings. Spicer’s debut press conference, on January 23, kicked off with the New York Post; the following day he gave the first crack to LifeZette, an overtly pro-Trump website run by conservative talking-head Laura Ingraham.

Since then, Spicer’s let a fairly mixed bag of outlets get the first question, and when Trump’s on the podium, sometimes the only questions have come from right-leaning organizations, such as Monday, when the only two reporters he called on during a joint press conference with Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau came from the Daily Caller and Sinclair Broadcast Group.

That Spicer shuffles up the order in his daily briefings and that Trump only calls on the organizations most likely to flatter him were noteworthy details in mid-January. Yet nearly a month later, people are still clucking about it as though it’s the biggest media controversy around.

A better criticism that some, including CNN’s John King and the New York Times‘s Glenn Thrush, have made is that the questions asked by the likes of the New York Post, CBN, and Townhall evade the biggest story facing the White House right now: Michael Flynn‘s dismissal as national security adviser. Brody’s question touched on Russia but focused more on how Flynn’s departure will affect relations with Iran, while Pavlich asked Trump and Netanyahu about Israeli-Palestinian affairs.

But that critique still clings to some propriety about who gets to ask the White House questions and in what order those questions should be asked. In the context of a press conference—especially one as heavily choreographed as one with the President and a foreign leader—does it matter? A White House briefing almost never contain big news in and of itself. It’s cattle-call journalism at its purest: a review of the President’s schedule, a rundown of the Administration’s upcoming policy agendas, and a few nationally televised questions asking the President or his spokesman to comment on the events of the day. If news happens, everyone gets it at once: There are no scoops in a press conference.

It’s safe to assume that Trump’s people probably strategized on how to minimize the chances of a difficult question. And even if they didn’t, their boss is Donald Trump, a man so given to dissembling and rambling at about his past achievements—he began his answer to a question about anti-Semitism with a recap of his electoral-vote total!—that the response often doesn’t line up with the prompt. (For what it’s worth, Pavlich has been tough on the White House about Flynn.)

Besides, if you want the closest thing to Trump’s take on an issue like this, the best venue is still early-morning Twitter. He chimed in this morning about reports of Russian influence in his inner circle.

This Russian connection non-sense is merely an attempt to cover-up the many mistakes made in Hillary Clinton's losing campaign.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) February 15, 2017

It’s not like he wasn’t just as defensive in person. When CBN’s Brody mentioned Flynn in his question, Trump reacted that his former security adviser had been “treated very, very unfairly by the media, as I call it, the fake media in many cases.”

Of course, we know this wasn’t the case. Flynn’s downfall came from dogged, investigative reporting–the Washington Post put seven reporters on the case; Vice President Mike Pence only learned Flynn lied to him after reading about it the Post.

Like the best stories about any presidency, stories like the Post‘s came from deeply established sources, document sleuthing, and careful analysis. So who really cares who gets first dibs on questions?