The morning of February 14, 1979, was cold and clear, a brilliant azure sky over the snow-capped peaks of the Hindu Kush ringing Kabul. As the city’s steaming teahouses ushered in a new day and the scents of turmeric and fig caught the breeze, Gul Mohammed was outside the American ambassador’s residence getting ready to drive him to work.

By 8:40 am, Mohammed had checked the car’s oil and wiped down the windows when Adolph “Spike” Dubs emerged in a turtleneck sweater and slacks. The 58-year-old ambassador greeted Mohammed in Dari, then jumped into the back seat with a days-old Washington Post and two letters to mail home.

Mohammed signaled the guardhouse and rolled the cream-colored Oldsmobile out into the city, US flag flying from the fender. He passed the Indian Embassy, a few shops, and the central post office as Dubs thumbed through the newspaper. It was all very ordinary until, near the Afghan Prime Ministry, a man dressed as a police officer stepped into the street and held up both hands.

The man said he had orders to search the vehicle, so Mohammed unlocked his door. At first, the stranger just glanced around Mohammed’s feet, but then he abruptly reached in to unlock the back. As he shoved a gun into Mohammed’s stomach, three others in street clothes suddenly appeared and piled in.

The men started giving directions and said that if Mohammed stopped for any reason, they’d shoot him on the spot. Dubs sat impassive, only telling the carjackers that he and Mohammed would cooperate if they lowered their guns, but the men ignored him. Finally, outside the Kabul Hotel, a favored lodging for diplomats, they made Mohammed pull over. One of them pushed his head down, leaving him to stare at the floor as the others hurried Dubs out of the back seat. Mohammed expected to die, but when he next looked up, the men—and the ambassador—were gone.

The carjacking was done in a flash. But the chaos that would unfold over the next few hours still echoes through American foreign policy four decades later.

At the embassy, political counselor Bruce Flatin and deputy chief of mission Bruce Amstutz were prepping for a morning meeting with Dubs when Mohammed pulled into the compound alone and confused. He kept insisting the ambassador had been “arrested.”

An embassy security officer immediately called the national police commandant for an explanation. The commandant seemed genuinely surprised at the news. Soon, one of the Afghan foreign minister’s subordinates called to clarify that the government had certainly not arrested Dubs.

Then what, Flatin wondered, had happened?

He climbed into the Oldsmobile, with Dubs’s rumpled Post and letters still in the back seat, and headed for the Kabul Hotel to investigate. When he walked into the hotel at 9 am, he found the lobby crowded with Afghan police. Flatin recognized a plainclothes officer by the half-dollar-size scar on his cheek—the man was a close aide to the commandant. The officer told Flatin that “terrorists,” not Afghan police, had snatched the ambassador and were now sequestered with him in a room upstairs. But he didn’t have any information about who the terrorists were, what they wanted, or why they’d targeted Dubs.

The story didn’t add up to Flatin. Why not go to some house way out in the suburbs?, he wondered. Or a safe house in the country, or a cave up in the mountains, where authorities couldn’t so easily corner them? Why would Dubs’s captors, whoever they were, hole up at a busy, central hotel, in a room with street-facing windows, no escape route, and not even a phone for conducting negotiations?

What’s more, Flatin didn’t trust Foreign Minister Hafizullah Amin—the “central bad guy” in Afghan affairs, as he called him—or his lackeys in the police. No telling, Flatin thought, whether the government could be tangled up in whatever was going on. He called the embassy with an urgent message: Send a doctor from the American clinic.

If anyone in the embassy could have helped Flatin puzzle out the mystery, it was the man who had been kidnapped. Kabul was the latest of numerous foreign postings in Dubs’s 30-year State Department career. He spoke German, Serbo-Croatian, and Russian and had served in Frankfurt, Monrovia, and Belgrade. In 1962, he was stationed in Moscow during the Cuban Missile Crisis, and he developed a reputation as one of State’s top Kremlinologists.

Dubs had grown up in Chicago, a son of ethnic Germans who emigrated from Russia to the US, and he came to State via the military. Along the way, he’d had a searing experience with violence. After joining the Navy as a junior officer just out of college, he was deployed on the destroyer USS Caldwell. One morning in 1944, off the coast of the Philippines, after emerging unscathed from the previous day of heavy fighting, the boatmen were feeling high-spirited and broke out in a chorus of “Oh, What a Beautiful Mornin’,” the opening number from Oklahoma.

Then, just after 8 am, Japanese planes attacked again and a kamikaze pilot crashed into the Caldwell. The clash killed 24 of Dubs’s shipmates. “Ever since,” his daughter, Lindsay McLaughlin, says, “my dad could hardly hear that song—it would just set him off.”

Dubs’s buddies called him Spike—a cheeky nod to his short, broad, un-spike-like build. (They didn’t think he should share a name with the German führer.) The nickname followed him into the Foreign Service, where fellow diplomats considered him “clear-eyed” and admired his “unflappable humor.” His athletic prowess was legendary. One colleague once said he “could whip just about anybody at Ping-Pong.”

According to the New York Times, at the grand opening of an American-style bowling alley in Moscow in 1974, after two Soviet officials christened the lanes with back-to-back gutter balls, Dubs rolled a strike, prompting raucous applause from his Communist counterparts. He so loved golf that he brought his clubs to Moscow, which had no courses. Local farmers marveled whenever he showed up in the fields to hit balls.

It was that disarming temperament, plus his Soviet expertise, that made him a logical fit for the ambassadorship in Afghanistan, where a Communist coup had just transformed the impoverished, landlocked country from a strategic afterthought to a Cold War flash point.

Why would Dubs’s captors, whoever they were, hole up at a busy, central hotel with no escape route or a phone to negotiate?

Before the coup, the US and the USSR had struck a comfortable coexistence in the country. In Kabul, American and Soviet diplomats collaborated on everything from amateur theater productions to golf tournaments. In the countryside, the Soviets oversaw aid projects in the north while the Americans led development in the south.

But with the Communist party now in power, that status quo was jeopardized. The Carter administration worried that Afghanistan’s independence would erode under pressure from the USSR—a jumping-off point for Soviet influence elsewhere in South Asia.

Still, Dubs’s appointment signaled that President Carter wasn’t ready to give up on cooperation, despite the urging of his administration’s hawks, who pushed for covert action to destabilize the new regime. Dubs saw promise when he first got to Kabul. Two days in, President Nur Mohammad Taraki told Dubs that he “wished to have excellent relations” with the US and that “Afghanistan would pursue a policy of nonalignment.”

Within a month, though, Dubs started to see that Taraki’s assertions were largely just talk. Russian advisers appeared in increasing numbers across the Afghan government, Soviet-made tanks guarded key locations around the city, and the regime gradually withdrew from working with American business and aid programs.

Amin, the foreign minister, was consolidating power around himself, marginalizing President Taraki. He also began blocking US staff from meeting with government officials in any ministry.

In search of help beyond his embassy staff, Dubs turned to Tom Gouttierre, director of Afghan studies at the University of Nebraska. Gouttierre had previously lived in Afghanistan with the Peace Corps and Fulbright programs—he even became head coach of the national basketball team. Because of Gouttierre’s academic reputation, Dubs figured, he could spend a couple of weeks feeling out friendly officials in the regime without raising too many eyebrows.

But Afghanistan had changed since Gouttierre left. The days of young women in short skirts buying Beatles albums in record stores—Afghanistan’s golden age—were over. At every ministry he visited, he got a cold reception. “What struck me the most,” Gouttierre says, “was the Afghans I knew well—my friends—were very apprehensive for themselves, for their safety, just because they knew Americans.”

Ten days into his stay, Gouttierre got a cryptic phone call from a friend in the Foreign Ministry, who suggested he cut his visit short. Two days later, Dubs had a diplomatic car hustle Gouttierre across the border to Pakistan. The following night, Dubs later told Gouttierre, Afghan police showed up at the ambassador’s residence to demand Gouttierre’s arrest.

It was the middle of the night in Washington when Anthony Quainton’s phone rang. The State Department’s counterterrorism director was asleep at home near National Cathedral. Now staffers at State’s emergency operations center were calling to tell him that a classified cable had just come in from Kabul: Spike Dubs was being held hostage.

Quainton was in Foggy Bottom within the hour. Updates began spilling in, but details were fuzzy. Afghanistan was one of State’s most remote diplomatic outposts. Much of the information had to flow from the hotel to the embassy via radio and then from the embassy to Washington by telegraph—this as simultaneous trouble at the embassy in Tehran was overwhelming the wires. Once the phone connection to Kabul was finally established, it proved spotty.

Quainton had direct links to the CIA, NSA, Pentagon, and White House. Still, he realized there was little Washington could do. The best and only option was to insist on negotiation, especially considering that Afghan security forces had a reputation for being ill-trained and unreliable.

“One thing we always worried about in hostage situations was that the host government would use force,” Quainton says. “You never want to do anything hastily, because things can easily go wrong.” He sent word to use patience.

Back at the hotel, a Soviet adviser showed up, a sign Flatin took as a positive development—Soviets were at least pros.

Flatin managed to convene a powwow between the adviser, Afghan police, and his embassy colleagues. He did his best to impress the need for a cautious approach, although communication wasn’t exactly straightforward. It was more like a game of multilingual telephone. The Soviet adviser spoke Russian to an Afghan officer, who translated for one of the embassy’s Afghan employees, who translated into English for Flatin. Flatin nonetheless had the sense the Soviets agreed with his position.

Not long afterward, however, it appeared that Flatin might be cut out of some of the decision-making process. He watched the Soviet adviser and Afghan police take a conversation to a corner of the lobby. As they turned their backs and began to whisper, he worried about what they might be saying.

By 10:30 am Kabul time, the cables broadcast back to Quainton suggested that the situation was tense but under control. One described the lead Soviet adviser as “calm and thoroughly competent.” Another anticipated a long, drawn-out negotiation: “[We] recommend Department should send expert immediately to Kabul. Conceivably the terrorists could be holed up with Ambassador Dubs for days.”

Quainton felt hopeful that with time the embassy could get Dubs back safely.

As the morning wore on, though, the kidnappers’ demands remained maddeningly unclear. At one point, they sent word that they wanted three political prisoners in Afghanistan released; at another, just one. Yet the American government—with little leverage over a broadly anti-American regime—had no control over anyone in an Afghan prison. Why was Dubs the pawn in what was an Afghan problem? It didn’t make sense.

Lloyd Rotz, the American Embassy’s doctor, got a gurney into the clinic’s ambulance—a converted Chevy van equipped with a crash kit—and sped across town to stage a makeshift emergency station in the hotel. Rotz had had a family-medicine practice in Michigan but wanted a change and applied to work overseas for State. When he got the Kabul assignment, he recalls, “I didn’t even have a good idea of where Afghanistan was.” Now he was in a hotel filled with police and security forces at the scene of a geopolitical incident.

Flatin was still pushing for patience, and as far as Quainton could tell, the strategy sounded sustainable. A cable from the embassy around 11:30 am said the Afghan government “would do everything possible” to free Dubs safely and that “Amin was personally supervising developments.” Most reassuringly, Quainton’s team read in one message, the Afghans had “no intention to break into the room by force.”

However, right around the time those messages reached DC, a group of commandos rushed into the hotel, cocked their weapons, and went upstairs. One of Flatin’s colleagues radioed the embassy that an assault on the room suddenly seemed imminent.

An economic officer at the embassy named David Litt, meanwhile, got a call from a Belgian employee of the International Monetary Fund who had an office across the street from the hotel. The Belgian wanted to relay that he could see firemen leaning ladders against the hotel exterior. It looked as if soldiers with AK-47s planned to scale up beneath a window. He called back to add that another group had assembled with shotguns on a balcony.

Just as DC received a cable saying the Afghans didn’t intend to break into the room, troops rushed into the hotel.

Just as the situation looked to be spinning out of the Americans’ control, an Afghan policeman asked Flatin if he’d like to speak with the ambassador.

Flatin hurried upstairs after the policeman. When they reached the door to room 117, an officer pointed at the keyhole and told Flatin to shout through it. Flatin balked. “I could see getting a mouthful of bullets,” he remembers thinking, but the officer reassured him that the kidnappers had okayed the conversation.

“Mr. Ambassador, it’s Bruce!” Flatin shouted in German, in case Dubs’s captors knew English. “How are you?”

“I’m all right,” Dubs replied, though Flatin heard a strain in his voice.

The police wanted to know what the kidnappers had for weapons, so Flatin asked. But when Dubs said “revolver”—the same in German as in English—the kidnappers suddenly shouted down the conversation.

The situation had obviously escalated, but the Afghans wouldn’t back down. They pushed Flatin to yell one more thing. Tell Dubs, they said, to either go to the bathroom or drop to the floor in precisely ten minutes.

Flatin couldn’t believe it. Clearly, the Afghans wanted to raid the room, guns blazing, against the Americans’ wishes—only three hours into the standoff. There was no way he was going to put Dubs in jeopardy like that. He refused to relay the message.

An Afghan officer protested that he had orders to follow, though he didn’t say from whom. By now, several Soviets were on the scene and Flatin again stressed the US’s position: that peaceful resolution should be the goal.

The police seemed to back down briefly, but then, right around noon, an Afghan officer suddenly told Flatin to send for medics. Flatin continued to object to any precipitous action but summoned Rotz and several other Americans with a stretcher nevertheless. The men watched in disbelief as a Soviet adviser began handing out guns to members of an assault team.

A colleague of Flatin’s radioed the embassy, which got the telegraph operator to wire Washington with the exact opposite of the message it had received barely an hour earlier.

“Flash,” the cable said. “Hotel group reports that break-in is scheduled.”

The attack started at 12:50—four hours after the kidnapping. An Afghan policeman in body armor lay down in front of the door to room 117 and trained his gun straight ahead. A Soviet adviser seemed to communicate via hand signal with forces across the street. Then Rotz and Flatin heard a thud—the assault team knocking in the door—followed by 40 seconds of gunfire so intense that Flatin felt the floors shake. It came from the hall and from across the street, where Afghan troops had lined up outside Dubs’s window.

As soon as the firing stopped, Rotz’s team started down the hall with the stretcher. But they froze at the staccato bursts of several more shots. When they reached the room, blue-gray gun smoke still clouded the entryway. The shades were drawn and the lights were off. Chunks of plaster littered the floor, and water from a shot-out radiator had soaked the carpet. “A gnat could not have flown in that room and not been hit by a bullet,” Flatin remembers.

Dubs was slouched in a chair, his body partially wet as if he’d fallen on the drenched floor and then been propped back up.

Rotz got him on the stretcher and out to the ambulance, blood streaming from his chest and head. Flatin stayed upstairs and watched as police dragged two kidnappers’ bodies out of the room. Both looked dead. A third, whom police had captured earlier elsewhere in the hotel, flailed at his captors. The fourth was nowhere to be found.

Mayer Stiebel, a tourist from Illinois, had been waiting in the lobby to retrieve his bags from his room. He’d just come back from a morning of sightseeing and had a flight out that afternoon when he heard the “tremendous” barrage. Even downstairs, his knees buckled. Afterward, on his way upstairs, the steps were so slick with blood that he had to concentrate to keep from slipping. The hallway was deserted, and a door just down from his own was open. When he peered in, he saw that an interior glass door and the exterior window had been reduced to shards. The walls looked like Swiss cheese, and smoke still tinged the air.

Out in the ambulance, Rotz was frantically doing CPR on Dubs. The ambassador didn’t have a pulse, and his expression was blank. “I just took one look at him,” Rotz remembers, “and knew he was dead.”

Back in 1973, during his second stint in Moscow, Dubs was rattled one day by news that terrorists had taken hostage and then killed an acquaintance of his, Cleo Noel, the US ambassador to Sudan. It “came as quite a shock,” he confided in a letter to his daughter, Lindsay. “I personally don’t like to think of being any kind of martyr; but if I were ever taken . . . I would want Washington to understand that I would rather sacrifice my life than to have someone capitulate to the demands of terrorists.”

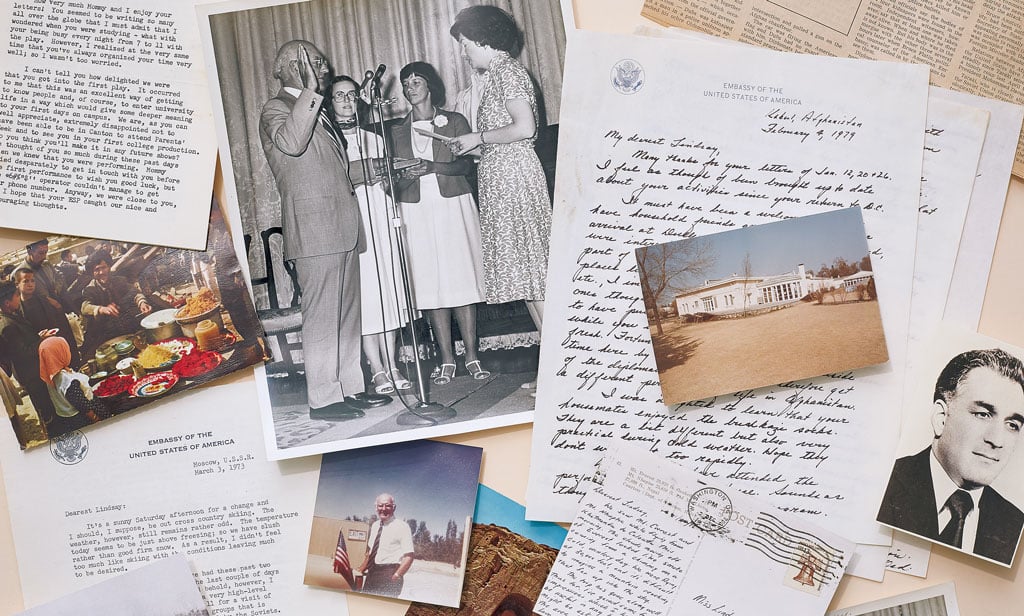

Lindsay, now 62, was adopted by Dubs and his first wife in 1954. She accompanied her parents to some of their early postings, then spent her teenage years in Bethesda while her father worked in Foggy Bottom. By the time he was back in Russia in the early ’70s, she was starting college at St. Lawrence University in upstate New York. In her stead, Dubs took a painted portrait of Lindsay from childhood—laughably large, she recalls—to hang in the Moscow home.

It was then that Dubs became a prolific correspondent, writing hundreds of pages of letters to his daughter. She still has them, stored in a box in her son’s attic in Mount Rainier. “My dearest Lindsay,” Dubs would begin, then write about his regret over missing parents’ weekend or send a reflection on faith and theology. He told her about the interesting people he met through work, such as when he sat across from Henry Kissinger at a dinner and spent much of the evening discussing ballet, having discovered that the foremost practitioner of realpolitik was a classical-dance aficionado.

In 1975, Dubs returned to the States for a stint in Foggy Bottom. Lindsay, meanwhile, began working and living in Columbia Heights with Sojourners, a Christian community founded by prominent evangelist Jim Wallis that crusaded against war, poverty, and corporate greed. The group’s zeal didn’t particularly jibe with Dubs’s mellow Unitarian Universalist leanings, and its activist ethos didn’t fit his studied, moderate brand of politics. But, Lindsay says, her dad “was just one of those really open-minded people.” Eager to be a part of Lindsay’s life, he’d tag along to Sojourners meetings—free-spirited affairs, Lindsay says, with lots of singing, swaying, and exclamatory praying.

If I were ever taken, I’d want Washington to understand that I’d rather sacrifice my life than capitulate to the demands of terrorists.

When he was posted to Kabul three years later, in 1978, the correspondence continued. About two months into the job, Dubs wrote that a recent visit from his second wife, Mary Ann, had buoyed his spirits even as he increasingly realized the difficulty of his mission. (Mary Ann, a young editor at the Congressional Record, had stayed back in Washington for her job.) Lindsay made it over to Kabul in early December and stayed through Christmas. During the trip, she was charmed by the locals and awed by the organized chaos of the bazaars. She wrote friends about hashish (Kandahar was the best place to get it), burkas (she sketched a diagram), and the pervasive tension around the political situation (“I have never felt anything like it”).

But despite the trouble the regime was having, especially with insurgents in the countryside, Dubs had no reservations about traveling freely. “I mean, we went la-di-da all over the place,” Lindsay says. “We drove to Bamiyan. We went over the Khyber Pass to Pakistan. We went traipsing all over, and I didn’t pick up any sense of fear or anything like that.”

Barely a month later in Washington, Lindsay got together with friends one night to see State of Siege, a French film based on the real-life abduction and murder of a US diplomat in Latin America. She slept fitfully after that, until the small hours of the morning, when Mary Ann called to say kidnappers had taken her father. It wasn’t long before Foggy Bottom got the last cable of the crisis—“Amb is dead”—and Mary Ann called Lindsay back, her voice choking.

The next days were a blur, though Lindsay felt preternaturally calm. She later described herself as if in a “tower of remote consciousness,” observing the chaos around her with hazy detachment.

In Kabul, the embassy staff grieved as they struggled to make sense of what had gone wrong. Flatin went to a military morgue to view the kidnappers’ bodies. This time, the Afghans showed him four. Two he recognized as the dead from the hotel room, another the accomplice who’d been very much alive, his body now covered in welts and bruises. The other Flatin had never seen before, but he assumed that because the Americans had reported four kidnappers, the Afghans figured they would produce four bodies.

“In Kabul,” Flatin says, “it was easy to get a fourth body—right out of the jail. So there he was, the fill-in.”

The government rebuffed Flatin’s repeated requests to inspect clothing and weapons, and he says that by the time any American was allowed back in room 117, it was entirely renovated. Dubs was dead, along with four supposed terrorists, yet still, no one knew their identities—or even whether they were in fact the masterminds.

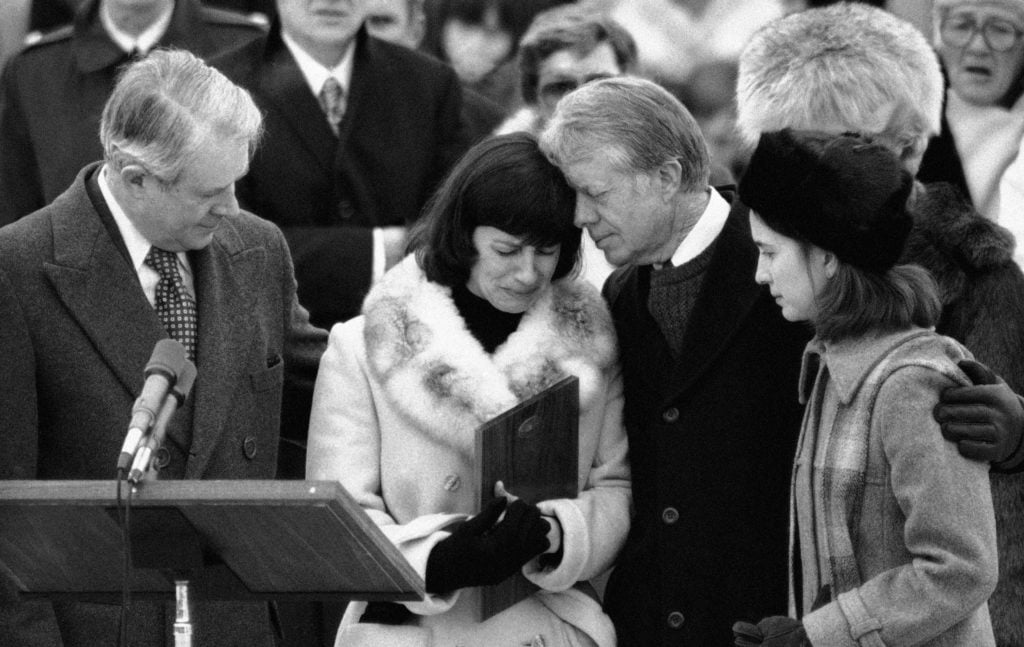

On February 18, President Carter met Dubs’s casket at Andrews Air Force Base, embracing Lindsay and a sobbing Mary Ann. Two days later, bright and cold, the ground covered in snow, Spike Dubs was buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Until Chris Stevens died in the 2012 Benghazi attack in Libya, Dubs was the last American ambassador killed at post. The policy fallout in Washington was decisive, swift, and lasting. The government cut off aid to Afghanistan and shrank its embassy staff in Kabul. “Rather than stick it out and try to offer an alternative to the Communist government,” says David Litt, the econ staffer, who later became ambassador to the United Arab Emirates, “we chose to scale down, hand everything over to the Soviets, and support the insurgency.”

Indeed, five months after Dubs’s murder—and five months before the Soviets invaded Afghanistan—American resources began flowing in secret to the mujahideen fighters in the country’s outer provinces. The Soviets fought a long, unwinnable war against the US-backed insurgency, the Taliban took over, and al-Qaeda took up residence. State didn’t place another ambassador in Kabul until after 9/11 and the US invasion of the country.

Yet while the assassination changed the course of geopolitics for at least four subsequent administrations, nearly 40 years after the fact, the identity of the architects of the carjacking and murder of Spike Dubs—as well as their motive—remains one of State’s most perplexing mysteries.

After the ambassador’s death, a team of doctors including Lloyd Rotz conducted an autopsy and concluded that the bullets that pierced Dubs’s chest and arms hadn’t killed him. A cluster of small-caliber shots in the side of his head had done that.

The ammunition is in line with the type of side arms carried by KGB, according to Flatin, maybe even like the weapons the Soviet advisers at the hotel had handed out to the assault team that broke into room 117.

To Flatin, Dubs’s death reeked of conspiracy—he wouldn’t be surprised if Foreign Minister Amin were behind it. “I don’t know why,” he concedes. “But it sounds like the kind of nutty idea Amin would have. . . . It was so clumsy that if you were told this was the plan, you wouldn’t have believed they could think up something so dumb.”

The Soviets, Dubs’s civilian envoy, Gouttierre, points out, were paranoid that Amin might actually be a CIA asset, on account of time he spent studying in the US. Gouttierre thinks the Soviets would have seen Amin’s consolidation of power and the arrival of Dubs as a dual threat to their influence in the country: “This was the height of the Cold War and all of the suspicions that went with it.” In that light, he suggests, the Soviets might well have orchestrated the assassination. He has since posed the theory to ex-Soviet military and intelligence people and says they’ve more or less intimated that, yeah, sounds like it could have been us.

Similarly byzantine explanations abounded. An Afghan who’d worked for the Peace Corps reported that her father heard from a government source that people in the regime had planned the murder and tried to pin it on Islamists to turn the US against the rising countryside insurgency. At a hearing on Capitol Hill, a congressman from New York asked about a rumor that the whole affair boiled down to a case of mistaken identity—that the kidnappers had confused the American ambassador with the Soviet ambassador, whose government was supporting the fight against the Islamist insurgency. Yet another theory, according to Warren Marik, a CIA officer in Afghanistan at the time, held that the kidnappers belonged to a leftist splinter group opposed to Western capitalism.

Ultimately, says Flatin, who’s now retired and living in Falls Church, “none of us who actually participated in this are satisfied we know the reason it happened.”

After burying her father, Lindsay McLaughlin continued to live and work at Sojourners for another seven years, then moved to Mount Rainier, and eventually got into teaching. Today she lives on a 1,400-acre nature preserve and retreat center near Charles Town, West Virginia. Mary Ann Dubs, inspired by her husband’s model, joined the Foreign Service, getting her first assignment abroad in Mexico City. Six years after Dubs’s death, she died of leukemia at age 40.

In Kabul, life gradually regained its normal rhythms. By March 1979, the diplomatic community’s amateur musical-theater troupe decided to forge ahead with a performance it had been preparing, with a 27-piece orchestra, a cast spanning 16 nationalities, and a contingent of dancing, singing US Marines. The only thing missing was Dubs. He was supposed to play a doting father in Kabul’s rendition of Oklahoma.

Correction: An earlier version of this story said Adolph Dubs was the last diplomat to be killed at post until Chris Stevens’s death in 2012. This is incorrect. Dubs was the last ambassador to be killed at post until 2012. Other American diplomats have been killed at post between 1979 and 2012.

Will Grunewald, a former Washingtonian assistant editor, is associate editor at Down East magazine in Maine. He can be reached at grunewald.will@gmail.com.

All photographs and newspaper clippings courtesy of Lindsay Mclaughlin, Beatrice and David Litt, and Library of Congress, and by AP Images. Collages photographed by Jeff Elkins.