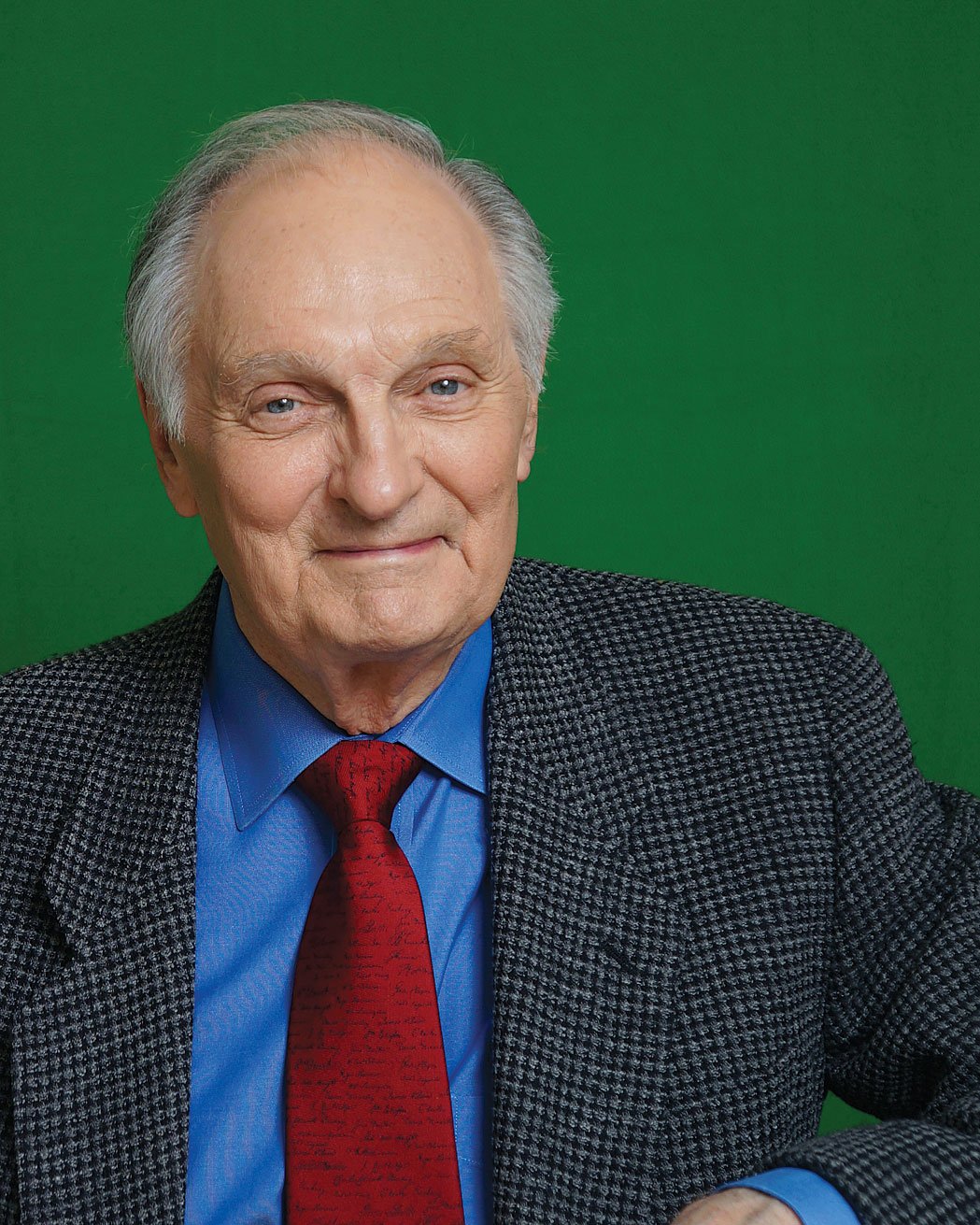

Alan Alda may be a film and TV legend, but lately he’s been thinking about science. In 2009, he founded the Alan Alda Center for Communicating Science, at Stony Brook University, which trains science professionals to talk to the public about their work with more clarity and ease. His new book, If I Understood You, Would I Have This Look on My Face?—which he’ll discuss at a Smithsonian Associates event Thursday—explains how improved communication in every field, especially science, can change our lives for the better. Alda spoke with Washingtonian about his passion for the cause of communication.

How did you come to make reading and relating to others the theme of the book?

I learned about it in a very personal way as an actor. You can stand there and say lines to the other person, but unless you’re open to what the other person is going through, they’re not making you say the lines, you’re just saying them because they’re in the script. It’s dead, it looks like acting, it doesn’t look like life. And life isn’t like life when all you’re doing is waiting for the other person to finish talking. This turns out to apply to everybody. Almost every situation involves communication.

How have your experiences as an actor shaped your thoughts on communication?

M*A*S*H was another time when I learned something about communication that I didn’t know I was learning. We knew we had to be close as characters and yet none of us had ever met before. We started immediately spending time with each other every minute we could on the set. And whereas most actors go back to their dressing rooms and read or study their lines between shots, we would sit in a circle and make fun of one another and make each other laugh. That brought us together in a way that was unusual, in a way I had never seen before. It was carried over into the performances in front of the camera. When I work on a play, I try to do the same thing now. If we can sit together laughing for an hour before a performance, that’s the best preparation.

Why has science communication in particular become a passion for you?

Well, I love science, and I’m in awe of what scientists are able to figure out about the world around us. To me, it’s like great music or great literature. It’s a look at the world, the whole universe we live in, that’s an astonishing detective story. And I want other people to have the pleasure of that. That’s the biggest reason; a less important reason is that if science isn’t understood better by everybody, we’re all going to perish. That’s also kind of important.

You have this extreme appreciation for science and you advocate for it without actually being a scientist.

Well, I know my limits. I value my ignorance because I’m curious. Ignorance all by itself is not so useful, but with curiosity, if you know what you don’t know and want to know more, then you’re on the road to some place. It’s really important to be aware that you don’t know something and to try to understand it as well as you can.

How do you think this current administration and political climate are affecting communication?

If cuts are going to occur at anything like the level that’s being suggested, communication of science is going to be even more critical. To avoid cuts that are so deep they hold back science, communication is going to be critical, because we have to understand that science in every culture is an engine of growth. In our culture, it may be the most important engine of growth. More than a hundred years ago, Einstein figured out general relativity, which had no practical application at the time. Now, we’re all walking around with GPS in our pockets, which wouldn’t be possible without what Einstein learned. It’s important to know things, and to have as much knowledge as you can about the universe.

How do you think your character Arnold Vinick from The West Wing would fit into this administration?

Well, the joke has always been that he would never be nominated. He’s probably too moderate for modern politics. But I had a wonderful time on that show, especially the episode where we had a presidential debate. It felt like an improvisation because it was being rewritten up until the last minute and we didn’t have time to learn it. We were getting it off a prompter and yet we had to make it look like it was spontaneous speech.

Have you given any thought to what your legacy will be, whether in acting, writing, or scientific communication?

No, I haven’t. When I’m dead, I’m finished. If I can leave behind something that’s helpful, whether it has my name attached to it or not, that’s great and that’s one of the reasons I’m working so hard on communication. Legacy, to me, means that your name is on it, and not having that doesn’t bother me.

What do you hope people take away from this book?

Each other.