Tonight shouldn’t be a jittery gig. Only about 100 gray-haired, nice-as-pie comedy fans have made it out to the Five Star Dinner Theatre, here in Hot Springs, Arkansas, population 37,000. Before the show, the owner will lead a rendition of “Happy Birthday to You” for an audience member, and afterward, “master magician” Scott Davis will take the stage.

But tonight’s headliner isn’t a local. It’s Yakov Smirnoff, Ronald Reagan’s favorite comedian.

For a man who hasn’t been heard from since the early 1990s, this isn’t just another Friday-night show—it’s a critical step toward his big comeback, or at least he hopes so. “I’m probably the only person on the planet that is kind of happy that the [new] Cold War is happening,” he says. “I’ve been waiting for 25 years.”

Smirnoff was the king of Cold War humor, the lovable Russia-born comic who disarmed US audiences with his “What a country!” punchlines as Reagan and Gorbachev piled up their nuclear warheads. He cracked up talk-show hosts by lampooning the Evil Empire with gags like “On the Fourth of July in Russia, we had fireworks, too. They’d put you against the wall and fire. It works.” And this: “There are no things like American Express [cards]. They give you Russian Express: ‘Don’t leave home.’ ”

But the fall of the Soviet Union toppled Smirnoff’s career. As pop culture moved on, America’s comrade in comedy plunged into obscurity, and his subsequent attempts to reclaim the spotlight failed again and again. Until . . . maybe . . . now?

I’m probably the only person on the planet that’s kind of happy the new Cold War is happening. I’ve been waiting 25 years.

As US/Russia relations have returned to the national water cooler, Smirnoff has been huddling with an unlikely team of joke writers, crafting a fresh routine about Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin, and turning up on any stage that will have him—like here in tiny Hot Springs. “Hi, my name’s Yakov Smirnoff,” he tells the crowd. “I’m Donald Trump’s favorite comedian. Not because I’m funny—because I’m Russian.”

Over the next four days, he’ll road-test his refurbished act:

“Donald Trump’s hair is like the United States right now—one half doesn’t get along with another half. And Putin’s hair is like Russian economy—it’s receding.”

“I think [Trump and Putin are] going to get along. I think they’ll find some topics that they can talk about. Like health care. Putin can share some, you know—they have free health care [in Russia] for years. They don’t do preliminary testing. They just go straight for autopsy.”

“Trump likes to fire people. And Putin likes to fire at people.”

After each punchline, Smirnoff will scrutinize the audience’s reaction not just to determine which jokes have a future but to see if Russian/American hysteria can make him a celebrity once again.

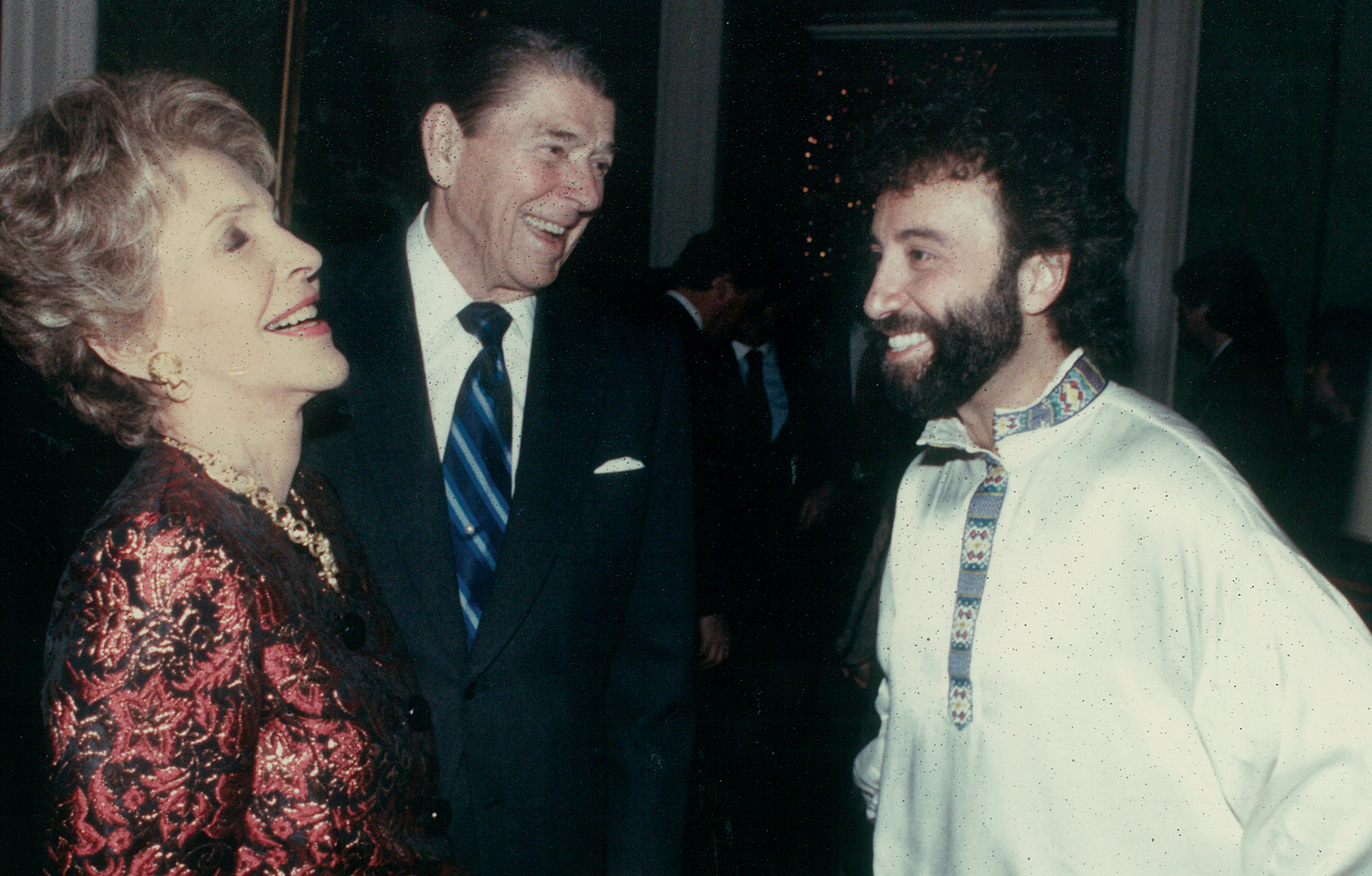

Smirnoff owes his original act to Washington. One evening in 1985, Arnaud de Borchgrave saw Smirnoff perform at a comedy club in downtown DC. After the set, de Borchgrave, top editor of the Washington Times, the then-influential conservative newspaper, and a well-connected figure in Republican circles, pulled Smirnoff aside: Would he like to attend a dinner party with President Ronald Reagan at his home in a couple of weeks?

The show-biz President was a lifelong fan of comedy in general and of Soviet jokes in particular, and de Borchgrave thought he’d enjoy meeting the young Russian. Smirnoff said he’d love to go, and de Borchgrave paid for his plane ticket back to Washington from his home in LA.

By then, Smirnoff was living an American fairy tale. He was born in Joseph Stalin’s Soviet Union, and grew up in Odessa, a bleak port city in Ukraine where he and his parents shared an apartment with eight other families. He had little aptitude for academics or sports but got a thrill out of making others laugh, and after two years of mandatory military service, he landed a job as a comic on a cruise ship in the Black Sea. Because the government had banned jokes about politics, religion, and sex, Smirnoff had to submit his material to Soviet authorities for approval and watch out for the KGB informants who prowled the ship. The gig introduced him to American tourists, who—despite what he’d been told by Soviet propagandists—appeared much happier than his Russian comrades.

After concluding that they’d have a better life in America, Smirnoff and his parents spent two years trying to emigrate, and in 1977, when the communists briefly loosened immigration restrictions, the family arrived in New York City with no command of English and $50 in savings. Smirnoff began working as a bar back at a resort in the Catskill Mountains. During his breaks, he watched the comics performing at the theater, which allowed him to learn English and get back into standup. He ditched his given name, Yakov Naumovich Pokhis, in exchange for Smirnoff, hoping the vodka brand would be easier for Americans to remember.

In the late 1970s, he traveled to Los Angeles for an open-mike night at the Comedy Store, the legendary venue that incubated Jay Leno, David Letterman, and Chris Rock. Eventually, he became one of the regulars and made a name for himself as a fish-out-of-water immigrant who pilloried communist oppression. “In Russia, they don’t fire warning shots in the air,” he’d deadpan. “They shoot right at you as a warning to the next guy.”

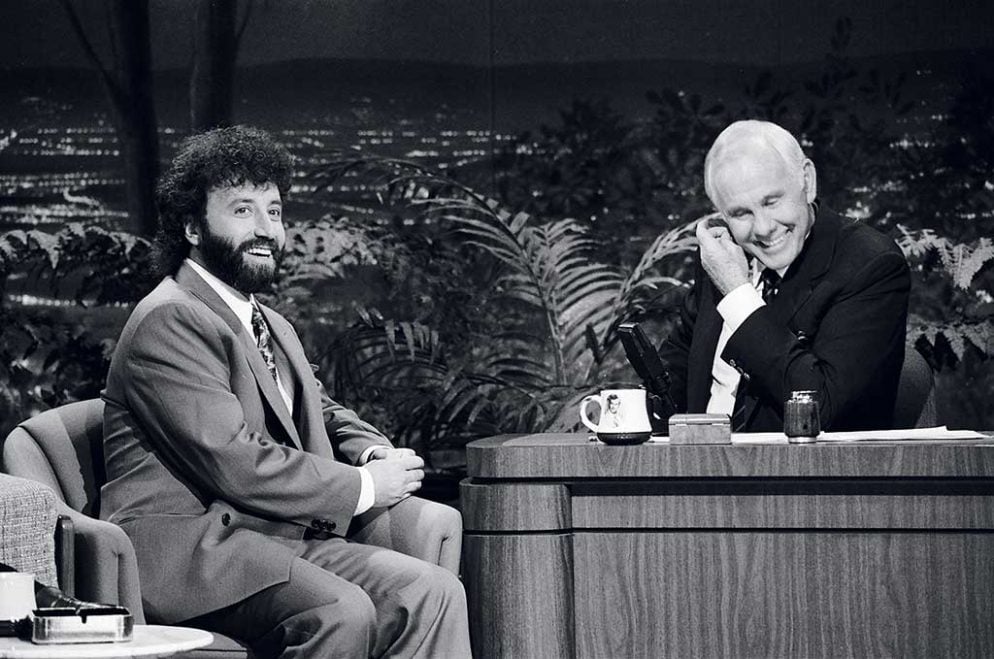

Smirnoff began performing on Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show, appearing as the wisecracking Russian in Hollywood movies, and starring in his own TV sitcom. “In America there is plenty of lite beer and you can always find a party,” Smirnoff told viewers in an ad for Miller Lite. “In Russia, party always finds you.”

When Smirnoff landed in Washington for the dinner party with the President, he and de Borchgrave got pulled over trying to get to the editor’s Kalorama condo. The Secret Service had cordoned off streets, and a federal agent was demanding to see de Borchgrave’s identification as helicopters buzzed overhead. De Borchgrave protested, but the agent insisted. Once he was finally satisfied, he turned to Smirnoff.

“Miller Lite commercial?” the agent asked.

Smirnoff nodded.

“Okay, go in.”

After the arrival of the 13 other guests—including Treasury Secretary James Baker, car-dealership magnate Mandy Ourisman, and the First Lady—Smirnoff met the President. The two immediately clicked and, according to Smirnoff, spent the rest of the evening trading Soviet jokes while the other guests keeled over in stitches.

Reagan told the one about a man who tries to buy a car in Russia, only to be instructed by the salesman to put his name on a list and return in 20 years.

“Should I come back in the morning or the afternoon?” the car buyer asks.

“What difference does it make? It’s 20 years from now,” the salesman replies.

“Well,” the car buyer says, “the plumber is scheduled to come that morning.”

Smirnoff countered: “In America, I can stand in front of the White House and say, ‘I don’t like President Reagan.’ In Russia, we have the same thing. I can go to the Kremlin and say, ‘I don’t like Reagan.’ ”

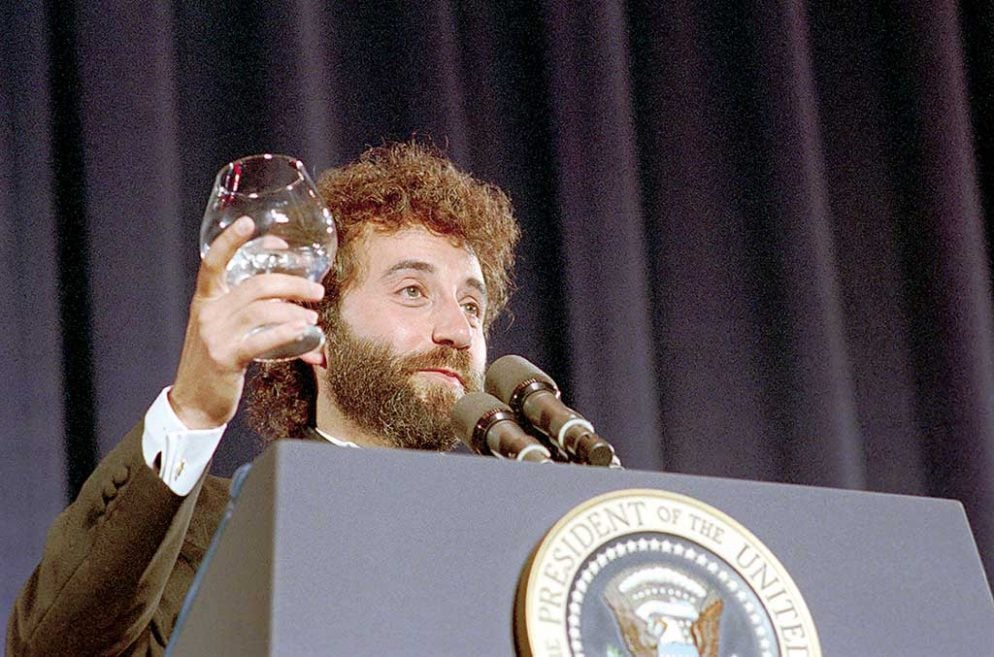

The Russian became the comic-in-residence of Cold War Washington, with gigs at the Conservative Political Action Conference, the White House Correspondents’ Dinner, and the White House itself. At the 1988 Republican National Convention, he led the Pledge of Allegiance.

Smirnoff also became buddies with Reagan’s young speechwriters, getting together with them for lunch at the mess in the West Wing and in their offices at the Old Executive Office Building. Soon, the White House was leaning on the comedian for more than gags. While academics could tell Reagan’s speechwriters all they needed to know about the Soviet government or economy, no one knew anything about what life was like for ordinary citizens. “It was like learning about the other side of the moon,” says former speechwriter Peter Robinson. “It was just in darkness to us.”

Says onetime Reagan speechwriter and current Republican congressman Dana Rohrabacher, now considered the most pro-Putin member of Congress: “If the President’s giving a speech about the Soviet Union, certainly on the list of people you’d call would be the CIA and Yakov Smirnoff.”

In April 1988, Smirnoff headlined the White House Correspondents' Dinner. Photograph by Ronald Reagan Presidential Library.

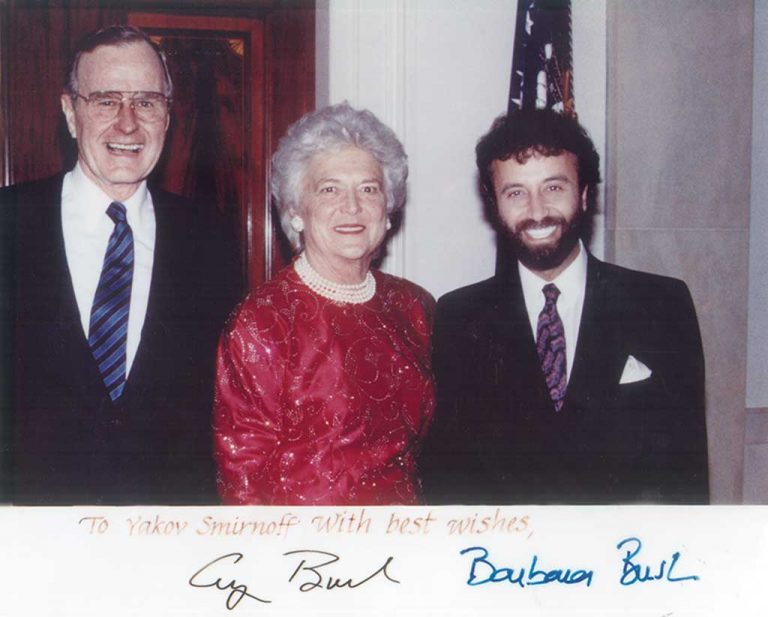

In April 1988, Smirnoff headlined the White House Correspondents' Dinner. Photograph by Ronald Reagan Presidential Library. Smirnoff with George H.W. Bush and Barbara Bush. Photograph courtesy of Yakov Smirnoff.

Smirnoff with George H.W. Bush and Barbara Bush. Photograph courtesy of Yakov Smirnoff.Rohrabacher recalls asking the comic to review a passage from a speech that went, “The Soviet Leadership is like a dog who is growling at you and wagging its tail at the same time. You just don’t know which end to believe.” Smirnoff told Rohrabacher the line would flop and insisted it be scrapped. When Americans think of dogs, they see cuddly companions, he explained, but most Russians were too poor to keep pets—they associated dogs with police oppression.

In early 1988, White House staffers began preparing for Reagan’s high-stakes summit with Mikhail Gorbachev in Moscow. The most critical address of the trip would be to the students of Moscow State University—never before had an American President been given the opportunity to speak directly to the Soviet people.

There was, of course, one person who could help.

Smirnoff provided a humorous parable to speechwriter Joshua Gilder, who wrote it into the final remarks:

“There’s an old story about a town—it could be anywhere—with a bureaucrat who is known to be a good-for-nothing, but he somehow had always hung on to power. So one day, in a town meeting, an old woman got up and said to him: ‘There is a folk legend here where I come from that when a baby is born, an angel comes down from heaven and kisses it on one part of its body. If the angel kisses him on his hand, he becomes a handyman. If he kisses him on his forehead, he becomes bright and clever. And I’ve been trying to figure out where the angel kissed you so that you should sit there for so long and do nothing.’ ”

Smirnoff watched the speech at home on television. But when Reagan delivered his punchline, the audience fell silent. For several seconds, no one reacted. The comic began to panic—talk about a bad time to bomb. Eventually, the interpreter finished translating the joke into Russian, and the crowd burst into laughter.

“Yakov Smirnoff,” Rohrabacher says, “was an incredible asset for Reagan. He took the rough edge off a lot of things while still making a significant point about the nature of the Soviet Union.”

The funny (or not so funny) thing was that while Smirnoff was helping his native and adopted countries end their historic standoff, he was tanking his act in the process. After the Cold War ended, his contracts in Las Vegas and Atlantic City weren’t renewed, and his film and TV work evaporated. At his peak, he had earned up to $30,000 a night. By the early 1990s, he was struggling to make mortgage payments on his $2.4-million house in Pacific Palisades, California, and was petrified about how he was going to support his wife and two young children. Where do I go?, he thought. What do I do?

One warm morning in July, about eight hours before curtain call, Smirnoff heads out to the back porch of the house where he’s staying in Hot Springs. He wears the same dark beard from his days as a celebrity, though he looks much younger than his 66 years. The porch is doubling as the writer’s room for today, and Smirnoff has assembled his partners—Skip Lotten, previously his massage therapist, and Alana Lotten, Skip’s wife.

As they discuss the upcoming show, Smirnoff receives a text with a fresh supply of material from another member of the team, a comedy-club emcee in Florida. Excited, Smirnoff starts reading the jokes aloud:

“I’m not sure how Russians got so good at computers all of a sudden. When I was there, Russians had not figured out how to even make stairs on an Etch A Sketch yet. We called tech support for help. Just kidding—we didn’t even have phones.”

The team is not impressed.

Smirnoff keeps scrolling until he finds a better prospect—a crack about Putin’s predilection for appearing bare-chested in photographs. “Not sure how the Russian economy is going, but it’s pretty bad when the Russian president can’t even afford a shirt when he goes out in public.”

Smirnoff chuckles.

“I like it,” Alana says. “Look at you—you’re laughing.”

After the Cold War ended, Smirnoff stopped getting calls to appear on late-night shows. Photograph by Gary Null/NBC/NBCU Photo Bank via Getty Images.

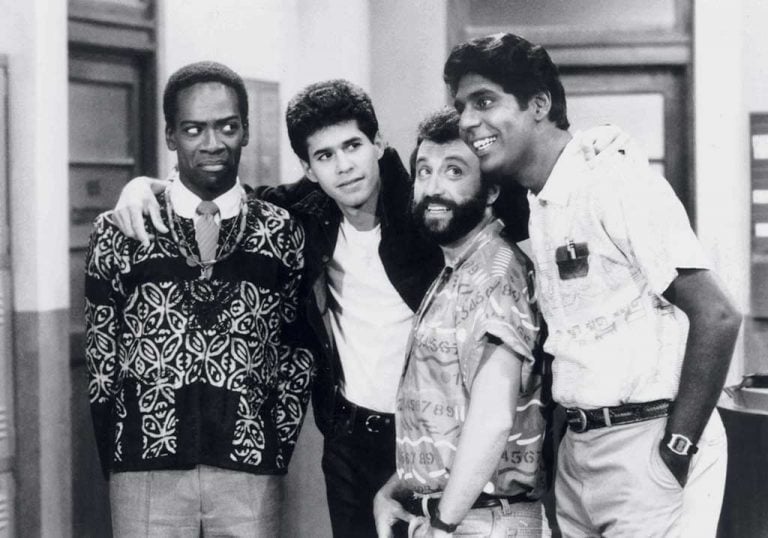

After the Cold War ended, Smirnoff stopped getting calls to appear on late-night shows. Photograph by Gary Null/NBC/NBCU Photo Bank via Getty Images. Smirnoff's sitcom, What a Country!, lasted one season. Later attempts were a bust. Photograph by Everett Collection.

Smirnoff's sitcom, What a Country!, lasted one season. Later attempts were a bust. Photograph by Everett Collection.Smirnoff formed his unlikely writing team in Middle America, during his long hiatus from the spotlight. He had settled in Branson, Missouri, at the suggestion of Willie Nelson. The country-music legend figured Smirnoff could still kill in the Midwestern mecca of clean entertainment, and he was right. Pollster Frank Luntz recalls visiting Smirnoff there in 2000 to film a segment for MSNBC: “We had to wait forever to interview him because the line of people who wanted to buy Yakov memorabilia was so long.”

Smirnoff jokes: “They did not know that the Soviet Union collapsed.”

Over 23 years, Smirnoff entertained more than 4.5 million people in Branson. He bought a 2,000-seat theater, occasionally rode a horse onto the stage, and played “The Star-Spangled Banner” at the start of each show. While he may have disappeared from the bright lights of New York and LA, in Branson Smirnoff was bigger than Elvis.

His act evolved with the changes in his life. After a divorce in 2001, he became fixated on the role of laughter in male/female relationships. He earned a master’s degree in psychology from the University of Pennsylvania and put his tuition to work in his 2016 PBS special, Happily Ever Laughter: The Neuroscience of Romantic Relationships. In it, the comic offered advice on “ending the Cold War between couples.” (He’s currently working on a PhD in education from Pepperdine University.) But no matter what he tried, Smirnoff could never retrieve his national audience. A one-man show on Broadway ran out of money only a couple of months after it premiered, and his efforts to develop a talk show, a reality show, and another sitcom all bombed.

One day this summer, Smirnoff received a text message from Luntz, with whom he’d remained in periodic contact. “It’s time to return to Russian political humor,” Luntz told him. “Putin Trump relationship should be a gold mine.”

Donald Trump’s hair is like the United States right now—one half doesn’t get along with another half. And Putin’s hair is like Russian economy—it’s receding.

Smirnoff was already on it. As the debate over Moscow’s role in Trump’s victory consumed the nation, he sensed that Americans would need the same type of release he’d provided during the Cold War. The tidal wave is coming, he thought, so I need to get my surfboard ready. He called up Skip and Alana, began drafting new material, and, in March and April, hit the road for a 12-show swing through Florida to polish the act.

When he arrived in Hot Springs, three days before the show opened, the first order of business was a crash course on Trump/Putin current events. Smirnoff is no Trevor Noah or Stephen Colbert—he doesn’t stay on top of the news. So along with Skip and Alana, he spent the better part of a day watching YouTube clips of Oliver Stone discussing his documentary about Putin, plowing through American press accounts of US/Russia relations, and perusing Russian news websites. When asked if they were credible, he responded, “It’s hard to tell.”

The US government’s onetime favorite comedian seems to want to reclaim that title—or at least ride the middle while his counterparts in late-night comedy take sides. “I want to make sure that I can perform this material in front of Trump, in front of anybody,” he says, “and people will not cringe.”

He tells me it’s not for him to say whether the Russians meddled in the 2016 election. During a recent trip to Russia, he came to view Putin as “a guy who 250 million [Russians] trust, and I’ve talked to a lot of them in real time and they revere him. It’s not like they fear him.” He considers both Trump and Putin to be well-intentioned heads of state who have been unfairly vilified by the media.

“They [are] both powerful leaders who want to protect their countries, who want to make them better, to make a difference,” he says. “That would be my job, to say: ‘Look how similar you are.’ ”

It’s tough to imagine this worldview bringing down the house in the liberal cities Smirnoff so badly wants to court. But here in Hot Springs—where county residents voted for Trump over Clinton by a 2-to-1 margin—he has no trouble making new fans.

Each evening at The Five Star Dinner Theatre begins the same way. After buying their $45 tickets, audience members fill their plates with barbecue ribs, mashed potatoes, and mixed vegetables from the buffet, then clap politely as Smirnoff walks onstage. His act is a mash-up of his long career—jokes from his 1980s heyday, a monologue about relationships based on his divorce and postgrad studies, and some experimenting with his new material:

“[Trump] met with president of China, and he has been criticizing China for years. And he had to find something good to say to the president of China. So he said, ‘I’m very impressed that you have a Great Wall. And it works—you don’t have any Mexicans there.’ ”

“So there’s a suspicion, obviously, that [Putin] messed with [Hillary Clinton’s] election. And she had problems with her e-mail—she got in trouble for using her personal server. Right? Well, come to think about it, Bill Clinton got in trouble for exactly the same thing. And Putin had nothing to do with that. She got off on criminal charges, and Bill just got off.”

“Melania [Trump] only just now moved from New York City to Washington, DC, because she was reluctant to live in government housing.”

Not all of the jokes land, but certain punchlines—the one about Hillary’s server, especially—produce explosions of laughter. Each set earns Smirnoff a standing ovation, and afterward audience members cluster around him for hugs and selfies.

“Wonderful show!”

“I’m glad you came to America!”

Once the crowd has cleared out after his final performance, Smirnoff sits alone at a table in the back of the club and exhales. He clicks through the evening’s jokes on his laptop and makes note of what worked and what didn’t. The four shows in Arkansas have encouraged him. “People are walking out going, ‘Your political stuff is great,’ ” he says. “I haven’t heard that in years.” He now feels prepared to face national audiences or offer advice to the Trump administration—should his phone start ringing again. “I’m probably the only Russian they haven’t talked to yet,” he likes to joke. “I kind of feel left out.”

As Smirnoff knows, he very well might never be called back into service. But you don’t get from the Black Sea cruise circuit to the White House speechwriters’ room without overcoming a little adversity. And Smirnoff isn’t ready to give up yet. Next week, he’s off to another gig, at a regional anime convention in Chicago. One step closer, he hopes, to his second American dream.

This article appears in the September 2017 issue of Washingtonian.

![Luke 008[2]-1 - Washingtonian](https://www.washingtonian.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Luke-0082-1-e1509126354184.jpg)