I’ve barely introduced myself, and David Rubenstein is trying to interview me: Where are you from? How old are you? Where did you graduate from? Mistakenly, I give the mouse a cookie, telling him the name of my alma mater. This sends Rubenstein into a fusillade of statistics—my college’s acceptance rates, attendance yield, current endowment. “No law school, though,” he says.

I was warned Rubenstein might try this, an interrogative parlor trick he picked up somewhere along the way to becoming co-CEO of the Carlyle Group—by some measures, the world’s largest private-equity firm—and perennial board member of galactic national institutions such as the Smithsonian and the Kennedy Center, plus about a dozen others. The cross-examination is especially fitted to his new extracurricular: talk-show personality.

At 68, David Rubenstein is now host of his own show on Bloomberg Television. The half-hour program—The David Rubenstein Show: Peer-to-Peer Conversations—plops him beside fellow CEOs of the billionaire class, with the occasional sports star and military general thrown in: Berkshire Hathaway’s Warren Buffett, Oprah, Coach K, David Petraeus.

The show, at first, raised eyebrows. Given his reputation—Rubenstein is known for an unprepossessing manner and an almost enforced personal awkwardness—the prospect of loosing him onscreen seemed about as plausible as asking Clarence Thomas to host Fear Factor. Indeed, Rubenstein’s not-made-for-TV persona turns up in every episode as he engages his subjects with a sorrowful deportment that appears vaguely related to sitting shiva. He scowls. He slouches. (He’s been advised, he says joshingly, to “sit up more straight.”) With a jaw that unlatches errantly and a gaze that wanders, he has the aspect of a man continually in deep recall for a geometry exam. But this is a setup, of sorts, for the show’s atonement: his oddball humor, which earns audience laughs during every shoot.

He asked GM’s Mary Barra if she pumps her gas (she does), Nike’s Phil Knight if he writes $400-million checks by hand (it’s complicated), and Morgan Stanley’s James Gorman if he uses a money manager (he does—guess who).

One might presume that awarding a prime-time slot (Wednesdays at 9 pm) to the most famous billionaire in Washington elevates the town’s gratuitousness to new heights. This summation would be correct if not for one thing: The show is doing well. Now in its third season, it’s one of Bloomberg’s fastest-growing programs. Viewership is up by 67 percent. A new agreement grants PBS affiliates nationwide the option to syndicate, meaning Rubenstein’s face could beam into every cord-cutter’s living room soon enough.

Like the other billionaire resident of Washington who rode prime-time television into national prominence, Rubenstein is capitalizing on the market’s clearest trend: a new regime in which magnates can, apparently, do anything—not despite the poor fit but perhaps because of it.

“The fact that he’s not a natural host is part of the odd appeal of the show,” says media critic Robert Thompson of Syracuse University’s Newhouse School. As Thompson puts it, “You have to wonder how a private-equity billionaire became good at TV. But that’s the thing. It really is good TV.”

How did a private-equity billionaire come to try his hand at television?

Rubenstein’s upward trajectory is a well-rehearsed tale. Born in Baltimore to parents of modest means—Dad was a postal worker, Mom a homemaker—Rubenstein became obsessed with studies in high school, the teenager who thumbed through multiple newspapers a day. A childhood friend recalls Rubenstein telling him he would be remembered as the hardest-working person anyone knew. Rubenstein graduated Phi Beta Kappa from Duke in 1970. (We did not discuss acceptance rates, attendance yields, or endowment). When he entered the Carter White House as a domestic-policy aide at 27, he spent so much time in the West Wing that he procured late-night meals from vending machines.

In 1987, Rubenstein cofounded Carlyle, without business experience. By the next decade, he had transformed himself into a virtuoso of private fundraising. Rubenstein was said to deliver his performances before would-be investors entirely without notes, memorizing sweeping details of markets and companies—and peppering clients with a level of inquiry that bordered on inquest.

“Some people win investors by backslapping and glad-handing—David was never like that,” one senior Carlyle employee says. “He comes in and astonishes them with his background knowledge of something.” (In a recent speech, Rubenstein said he aims to finish 100 books a year.)

Yet it took until 2008 before his inner extrovert began to inch out in public. That year, Rubenstein took over the Economic Club of Washington, a public-speaker forum for business types. “My only job was to get four speakers a year, bring them in, and introduce them,” he recalls. “You stand up after they’re done, and questions come from the audience. That’s it.”

Growing bored with earnest audience queries about things like earnings per share, Rubenstein began to ad-lib, pretending his questions came from the crowd. Once, he asked an auto executive, “What actually happens when a salesman goes back to ‘talk with the manager’?” Attendance grew, and the club notched a record in March 2011 when he interviewed Bill Gates and asked him if he had a credit card. The world’s richest man demurred but hastened to add, “I don’t have a problem carrying money around.” The crowd of mostly middle-aged men roared.

Justin Smith, who oversees Bloomberg Media’s television unit as CEO, remembers watching Rubenstein’s interview that day at the Ritz-Carlton ballroom and envisioning a show. “It’s uncommon for someone in his business and his level of success to be as granularly curious about people,” Smith says. “He has an entire philosophy about how to have an engaging conversation.”

The philosophy hinges on Rubenstein’s forte—obsessive preparation. He described his process to me in the clinical manner of an investment product: writing the bio, memorizing it, writing the questions, memorizing those. He’ll devour as much of the corpus of a subject’s work as he can—standard interview-show practice, though most TV gabbers don’t have a day job like Rubenstein’s. He’s a believer in unceasing eye contact—to mixed effect onscreen—and insists on dispensing with notes on the set. “It’s a crutch,” he says, “and I think it detracts from the conversational approach.”

Whether in conference rooms or interviews, Rubenstein is said to have a strategic humor quota. In the show, this manifests as a journalistic invention you might call a Rubenstein Question, along the lines of that early interaction with Bill Gates. He has asked Mary Barra of GM if she pumps her own gas (she does), Phil Knight of Nike if he writes his own $400-million checks out by hand (it’s complicated), and Morgan Stanley CEO James Gorman if he uses a personal money manager (he does—guess who).

“You’re going to be a little in awe of the President. I don’t mind asking prominent people questions that would be somewhat funny.”

Rubenstein administers all of this with the same dour expression seemingly cemented in place—a bit like fielding questions from a towering Easter Island head that secretes Jack Benny bits. Onstage, he’s given to energetic outbursts that interrupt stammering guests with diamond-cut one-liners, a humor curiously situated somewhere be-tween Borscht Belt and boardroom. The earnestness of the laughs can vary. Here’s one such applause line with Barra, in which Rubenstein asks about GM’s relationship with federal overseers:

Rubenstein: None of them ever say, ‘Can you get me a discount on a GM car?’ ”

Barra: “We can’t for government officials. So yeah.”

Rubenstein: “What about for people interviewing you?”

Barra: “If you’re not a government employee, I think we can work something out.”

“I had not realized what a sense of humor he has. He was asking things with a complete poker face,” says Annette Gordon-Reed, a Harvard history professor and a recent interview subject at one of Rubenstein’s Library of Congress events. “I had to look into his eyes to see that he was, somewhat, teasing.”

Previously, Rubenstein’s most visible public project was the pioneering of so-called patriotic philanthropy. He has used his $2.9-billion fortune—abetted by a generous tax allowance called the carried-interest loophole—to repair the Washington Monument, buy a 1297 copy of the Magna Carta, and restore Monticello, acts of patrimonial salvation that prompted 60 Minutes to declare him “Clark Kent in a suit and tie.” This represents a marked reversal from the days when Carlyle often found itself in the public stockades for bad judgment (shadowy defense deals) and bad luck (hosting Osama bin Laden’s half brother on 9/11). The Washington-sanctified bonhomie that glimmers across The David Rubenstein Show is the finishing ribbon on a multi-year project of reputation rehabilitation and, it must be said, an impressive one.

When I ask Rubenstein why he actually needed a television show, I expect some vision of service to the country or, failing that, the expanded brand name of Carlyle, which went public in 2012. Instead, he gives me a jovial and lengthy lecture on his philosophy of personal achievement, which he calls his “sprint to the finish.”

“Many of my classmates from college and law school, to the extent that I’m going to read about their obituaries, they’re retiring,” he says. “And I am actually doing the opposite. Instead of slowing down, I’m kind of speeding up.”

Two weeks after our first meeting, I met Rubenstein again, this time in the green-room at Bloomberg’s New York headquarters on Lexington Avenue. Before I could say hello, he burst into recall, quizzing him-self aloud as he launched once more into the details of my college. (He got them all right.) He clasped a sheaf of 38 questions, its margins vandalized with Rubenstein hieroglyphics, his prep for that day’s guest, Ginni Rometty, CEO of IBM. When I asked him how he thought Rometty was preparing for the segment, he seemed to swat the question away with his rolled notes: “I’ve interviewed her before. This is the least pressured thing she has to do today, I’m sure.”

In less than a year, Rubenstein already has a waiting list of public figures—CEOs mostly, with potentially some pop stars and a few politicians—keen for this treatment. This is hardly a mystery. The show’s opening credits feature B-roll of Rubenstein musing, “I don’t consider myself a journalist”—words that are then plastered across the screen in bad-boy graffiti, as if to refashion this protective disclaimer into something more renegade.

In 20 episodes, Rubenstein has asked approximately 735 questions. By my count, about 110 were Rubenstein Questions, 235 personal, and 320 job-specific. Some 70 were on policy or issues of the day. To his credit, these questions were worthy ones. He asked General Petraeus to diagnose the weapons-of-mass-destruction debacle at the CIA and Morgan Stanley’s James Gorman why Americans hate Wall Street. But the ensuing dodge from Rubenstein’s subjects rarely elicits a probing follow-up. Rather, his questions tend to revolve around overcoming the particular obstacles mounted by the onset of wealth and success, such as when he asked Gorman if he could get tickets to Hamilton easily.

Rubenstein presents his copy of the Magna Carta to the National Archives. Rubenstein's philanthropy helped nudge his public image from connected financier to national treasure. Photograph by Getty Images.

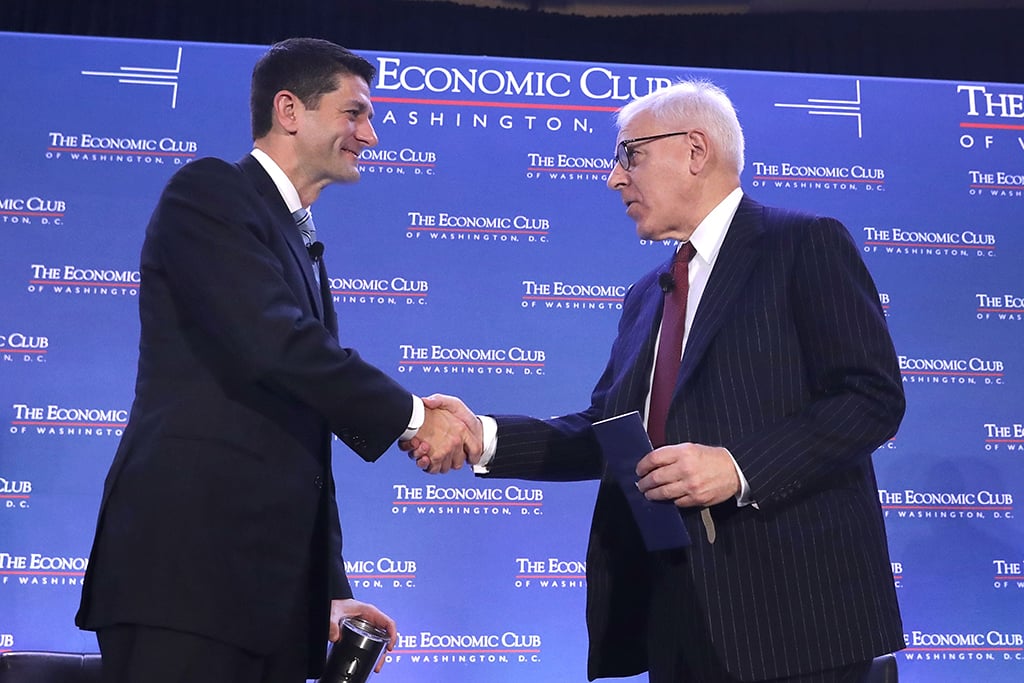

Rubenstein presents his copy of the Magna Carta to the National Archives. Rubenstein's philanthropy helped nudge his public image from connected financier to national treasure. Photograph by Getty Images. Rubenstein with Speaker of the House Paul Ryan. Photograph by Getty Images.

Rubenstein with Speaker of the House Paul Ryan. Photograph by Getty Images. Rubenstein with Oprah. Photograph courtesy of Jean-Pierre Uys Photography/Bloomberg.

Rubenstein with Oprah. Photograph courtesy of Jean-Pierre Uys Photography/Bloomberg.The curious law governing Rubenstein’s show is that the less famous its subjects, the more interesting the conversations. The third season, for instance, can range from former Presidents Bush and Clinton—an encounter in which Rubenstein doesn’t pose a single difficult question—to Francis Collins, who directs the National Institutes of Health and from whom Rubenstein, a secular Jew, unspools the former atheist’s fascinating journey of becoming a born-again Christian, making it unquestionably the best episode of all three seasons.

In a noteworthy sequence with Barra, Rubenstein prompted the GM chief to discuss a meeting at the White House. He asked, “What is Donald Trump like?,” to which Barra, discomfited, responded in part, “I would say it was a very productive meeting where we could share our views.” Rubenstein abruptly changed subject: “Why are you so successful in China? Do you manufacture the cars there?” The prospect of twinning the topic of outsourcing to the populist earthquake that had flung Barra next to Trump—thanks to a historic upset, no less, in her own back yard of Michigan—seemed to elude both interviewer and subject. Given his sagacious powers in business, viewers are often left to wonder why they don’t follow Rubenstein onto the stage. Camaraderie, not curiosity, is his stronger suit there, or so it would seem.

At this, Rubenstein puts up his hands. “Okay, okay, I get it,” he says. “Trying to give people a perspective on what makes somebody tick is probably what I’m interested in.” He goes on, “My job is not to embarrass somebody or put them on the spot, or make them feel squeamish about something. There are plenty of people who can do that. That’s just not me.”

The posture draws mixed conclusions from the guardians of the fourth estate. Dean Starkman, a former business-media critic for the Columbia Journalism Review who now teaches at Central European University in Budapest, says, “He’s a journalist. I don’t know what else you’d call it,” adding, “He’s letting himself off the hook.”

Thompson, from Newhouse, on the other hand, counts Rubenstein among the proto-journalists who adorn today’s media. At the expense of tossing knowledge out with the journalistic bath water, Thompson asks me to consider whether we would do without John Oliver, Samantha Bee, or Jon Stewart. “Look at Anthony Bourdain,” he says. “He may not be a journalist, but we get a lot of the same kinds of insights. And who did he interview? Barack Obama. Nonfiction information from a different mode than traditional journalism—I think it’s valuable.”

Just as with the late-night hosts who attempt it, though, this balancing act gets harder in practice. Consider Rubenstein’s biggest newsmaker interview, a 2014 session with Donald Trump at the Economic Club. Trump, reprieved from any interrogation about Trump University or his “birther” smear against Barack Obama, appeared to love the experience. Would Rubenstein do it again for Bloomberg? He’d consider it. But he says, “If you interview Trump and you aren’t asking tough questions, people will say, ‘Well, you’re not really a good journalist, because you’re not asking the tough questions.’ But if I were to interview Trump right now, I wouldn’t really want to go through all the stuff that every other journalist is asking about. . . . I would say, ‘Are you upset that your parents didn’t live to see you do this? Tell me what it was like when your parents sent you off to a military academy—were you happy with that?’ ”

The answers might offer some illumination into Trump’s soul (though Rubenstein already asked the military-school question of Trump back in 2014). For his part, Rubenstein prefers to think of his show as among the vanguard—a world in which one’s billionaire status grants certain indulgences that a workaday journalist, chasing the story of the day, might not pull off.

“You’re probably going to be a little bit in awe of the President of the United States,” he says, not incorrectly, adding, “I don’t mind asking prominent people questions that would be somewhat funny.”

He’s right. On the other hand, future historians might squint at the powerful billionaire who avoided pressing the leader of the free world on the big issues. Alternatively, perhaps—assuming we make it through this era alive—they’ll simply wonder why we couldn’t all be as sanguine as Rubenstein, who, after all, seems to be enjoying himself.

“I guess at this point in my life,” he says, smiling, before gesturing me toward the door, “I’m not that much in awe of that many people.”

This article appears in the November 2017 issue of Washingtonian.