One week into Donald Trump’s presidency, Ahmed Awad bin Mubarak, Yemen’s ambassador to the United States, received some unwelcome news. For days, foreign diplomats in Washington had chased rumors about a looming presidential order banning citizens of Muslim-majority countries from entering the US. Was Yemen on the list?

“We tried to investigate,” Mubarak says. His staff worked the phones, calling their US government counterparts. But in a new administration that disdained the permanent bureaucracy, the Americans they’d cultivated as insiders no longer had any inside dope. “We approached our contacts at the State Department and the National Security Council and asked them for information. They told us, ‘We’ve heard the same rumors. But we don’t know anything, either.’ ”

On January 27, the White House released the Executive Order on Protecting the Nation From Foreign Terrorist Entry Into the United States. It barred travelers holding Yemeni passports—as well as citizens of Libya, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Iran, and Iraq. At airports around the world, mayhem ensued. Dozens of Yemenis—including exchange students, family members of US citizens, and even green-card holders—were prevented from boarding planes, detained upon arrival, or sent home on return flights.

Mubarak assigned a team at Yemen’s embassy to set up a 24-hour hotline for stranded passengers and members of the Yemeni-American diaspora. In meetings with officials, he pleaded for Yemen to be exempted from the ban. Since September 11, 2001, no Yemeni-Americans have committed any terrorist attacks in the US. The two countries’ militaries have for years cooperated in the fight against al-Qaeda. What was the case against Yemen?

For a foreign ambassador, this is the moment to get to work, to blast out e-mails and rip through your iPhone contacts in search of some connection, some opening, that might give you a chance to make a bad situation right again, or at least limit the damage. It’s when all the skills of flattery and persuasion, honed through countless Washington cocktail receptions and courtesy calls, are supposed to pay off. In 2017, that dance has been trickier.

The start of a new administration is always a disorienting experience: Familiar names at federal agencies vanish, e-mails to National Security Council staffers bounce back, long-scheduled appointments suddenly get pulled down. But the antiestablishment revolt represented by Donald Trump—a President with no government experience, relatively few trusted advisers, and a disregard for foreign-policy professionals—along with the administration’s historically slow rate of filling senior positions, has magnified the challenge of figuring out where decision-making power lies. Months into the administration, a BBC journalist recounted hearing European diplomats in Washington discussing how they’d resorted to scrutinizing news photos of White House meetings, Homeland-style, to try to discern which officials had Trump’s ear. Said one: “There’s pictures of the Oval Office, and you’re like: Who’s that?”

At the height of the travel-ban crisis, Mubarak started making daily visits to 24-Hour Fitness gyms in Falls Church and Vienna to track down officials he couldn’t reach through normal channels. “We asked many questions but didn’t get answers,” he says, seated in a leather office chair on the second floor of Yemen’s stately Mediterranean-style embassy in Kalorama Heights.

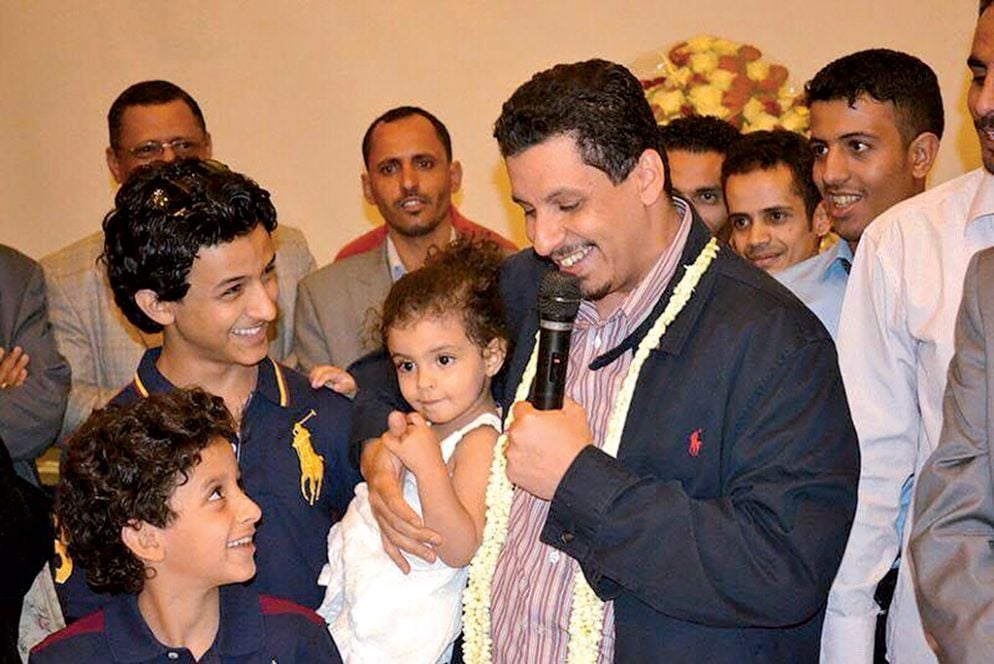

Mubarak, 48, has a stocky frame, thick black hair, and a prominent goatee. He’s the sort of naturally gregarious person who punctuates the end of every statement with a wide, disarming grin. He tells me his office received hundreds of e-mails, letters, and social-media messages from Americans expressing opposition to the travel ban. Mubarak mentions one of the largest demonstrations against the Trump policy, a February 2 rally in Brooklyn organized by Yemeni-American bodega owners that drew thousands of people waving Yemeni and American flags.

“It was huge, really huge,” he says with evident pride. When I ask whether he considered attending, Mubarak waves his hands and breaks into a smile. “This,” he says, “is very sensitive.”

Ultimately, it was US courts, not foreign envoys, that initially succeeded in halting Trump’s travel ban—until the administration replaced it with a new, expanded ban that prevents Yemenis from immigrating to the US or visiting for business or tourism. The Supreme Court promptly canceled hearings on the original executive order, but the revised policy will almost certainly face new legal challenges. Countries can also get themselves removed from the list, if the government decides the restrictions “are no longer necessary for the security or welfare of the United States.” For Yemen, the final outcome is as muddled now as it was in January.

In the meantime, Mubarak has other problems. He represents a war-torn country whose government doesn’t control its own capital and whose ambassadorial residence is so dilapidated that he and his family are camped out in a McLean rental. Yet in the chaos of Trump’s first year, Mubarak has also glimpsed opportunity. For several months, I checked in on him periodically to see how he was navigating the new regime. I found you can learn a lot about the way DC—and America—looks to the rest of the world by paying attention to the foreign representatives living right next door.

“You don’t have to order for yourself,” Mubarak says as we arrive for lunch at Saba, a tidy, inconspicuous Yemeni restaurant in Fairfax. “I called ahead.”

We’re at a corner table along with two of the ambassador’s young aides. Heaps of food materialize: salads, meat-stuffed sambousa, slow-roasted lamb with rice, and saltah, a vegetable stew topped with a whipped fenugreek paste. The owner comes out to greet Mubarak, who dines at Saba every other week. Mubarak mentions that several government ministers from Yemen are due to arrive for annual meetings with the World Bank and International Monetary Fund. Our feast is just a warm-up. “We’ll probably come back here this weekend,” he says.

The nation Mubarak represents is convulsed by war, famine, and disease. Pockets of terrorists operate in Yemen’s badlands, pursued by American drones and commandos. Much of the country—including the capital, Sana’a—is controlled not by Mubarak’s boss, President Abdu Rabbu Mansour Hadi, but by rebels known as the Houthis. The rebels receive support from Iran and from Hadi’s ousted predecessor, former president Ali Abdullah Saleh. As war rages, senior government officials, including Hadi, live in exile, venturing home only for occasional visits. Military air strikes by Saudi Arabia against the Houthis have killed at least 10,000 civilians. This summer, an outbreak of cholera sickened more than 500,000 people. The United Nations estimates that close to 20 million Yemenis —two-thirds of the population—need some kind of humanitarian aid in order to survive.

Mubarak was born to a prosperous family in Aden, the son of a businessman who worked for a variety of multinational companies, including Toshiba and Rolex. He left Yemen to attend university in Baghdad, where he met his wife, Ishraq, a fellow student from Yemen, and earned a PhD in business administration. He dabbled in politics and was elected as Yemen’s representative to the Arab League’s student union.

He and Ishraq returned to Yemen and settled in Sana’a, an ancient city famed for its earthy red mosques and tower houses. Mubarak joined the faculty of Sana’a University and became head of its center for business administration. He traveled frequently to Europe, hosted visiting scholars, and spent three months in the US on a State Department–sponsored fellowship. In the spring of 2011, popular demonstrations erupted against then-president Saleh, who had ruled Yemen for three decades. Mubarak emerged as a spokesperson for the youth activists in the negotiations that eventually forced Saleh from power. In 2013, he was tapped by the new president to oversee the National Dialogue Conference, a ten-month process that produced a framework for a new, pluralistic constitution.

“He was seen as a unifying figure, someone who could work with everybody,” says Gerald Feierstein, who was US ambassador to Yemen during that time. “He was diplomatic, articulate, willing to compromise and see the other side—which made him a relatively unusual character on the political scene.”

With his official residence in DC's Spring Valley in disrepair, the ambassador and his family are living in a rental. Photograph courtesy of Ahmed Awad bin Mubarak.

With his official residence in DC's Spring Valley in disrepair, the ambassador and his family are living in a rental. Photograph courtesy of Ahmed Awad bin Mubarak. The sea change in US policy has diplomats like Mubarak—here with Jordan's ambassador, Dina Kawar—working overtime. Photograph courtesy of Ahmed Awad bin Mubarak.

The sea change in US policy has diplomats like Mubarak—here with Jordan's ambassador, Dina Kawar—working overtime. Photograph courtesy of Ahmed Awad bin Mubarak. Mubarak, shown with Arizona Senator John McCain in 2013, is pressing the US for more humanitarian aid. Photograph courtesy of Ahmed Awad bin Mubarak.

Mubarak, shown with Arizona Senator John McCain in 2013, is pressing the US for more humanitarian aid. Photograph courtesy of Ahmed Awad bin Mubarak. Yemeni president Abdu Rabbu Mansour Hadi, right, was forced into exile in 2015 by militants loyal to his predecessor. Photograph courtesy of Ahmed Awad bin Mubarak.

Yemeni president Abdu Rabbu Mansour Hadi, right, was forced into exile in 2015 by militants loyal to his predecessor. Photograph courtesy of Ahmed Awad bin Mubarak.So unusual, in fact, that Hadi appointed him prime minister. In response, the Houthi rebels—who claim to represent Yemen’s Shi’ite minority—threatened a mass uprising to prevent Mubarak from taking the job, calling him a tool of the West. After nearly 36 hours, Mubarak withdrew and posted the announcement on Facebook before informing his president, who instead made Mubarak chief of staff. By then, the Houthis had seized control of the capital and begun taking steps to topple the government. They started by kidnapping Mubarak.

He relates the story of his abduction midway through our lunch. As he speaks, he breaks off pieces of flatbread to soak up the pools of sauce collecting on his plate.

On the morning of January 17, 2015, Houthi gunmen seized Mubarak and two bodyguards. They drove to seven different locations and finally brought Mubarak to an office building on the outskirts of Sana’a. “In the beginning, I thought it would just be a couple hours,” he says. “We were in the middle of a political process. It seemed like a mistake.”

His captors tied his hands and accused him of being an American spy recruiting Yemenis to join the CIA. Mubarak refused to talk and insisted on calling his wife. “We are fine, don’t worry about us,” she told him. “Be as strong as I know you are.”

Mubarak looks up from his food and speaks softly: “From her voice, I could tell she was still very strong, which surprised me. Until this day, I’m very proud of her courage.”

The Houthis kept Mubarak isolated in darkness, then woke him for interrogations. He says he knew one captor personally, from working with him during the negotiations over a new constitution. He was told that the president was hellas—finished. “Internally, I prepared myself,” he recalls. “Either they’ll kill me or not release me at all.”

But after nine days, the captors put Mubarak into a car and drove for three hours, then led him into the house of one of his friends. He was told to leave the country within 24 hours. Mubarak, his wife, and their two younger children left “with only the clothes on our back,” he says. (Mubarak’s eldest son, Khaled, was studying in the US on an exchange program.) He has never returned home. “They took everything from me, and they didn’t give back anything.”

Yemen has been at war ever since. Mubarak supports a political, negotiated solution to the conflict, but it’s clear that he takes a dim view of ever compromising with the Houthis.

“He’s bitter at what happened to him, and I can’t blame him,” says Feierstein. “When he was chosen to be the secretary general of the National Dialogue, everyone had to sign off, including the Houthis. These were people who accepted him and presumably respected him. Yet they turned around and treated him like that. He’s become much more hard-line, and I think that comes out of an element of personal commitment and hurt.”

Which brings us back to Trump. During the last months of the Obama administration, Secretary of State John Kerry tried to broker a peace settlement in Yemen, going so far as to meet with representatives of the Houthi rebels. The gambit infuriated the Hadi government. Mubarak believes that Obama’s last-minute attempt to strike a deal reflected a flawed foreign policy that tilted too far in favor of improving relations with Iran. Trump’s national-security team has taken a more hawkish line against Iran and eased pressure on Saudi Arabia to scale back its air campaign against the Houthis.

Eric Pelofsky, a former senior director for North Africa and Yemen on Obama’s National Security Council and a friend of Mubarak’s, says that while some diplomats refuse to consider opposing points of view, “I never found that to be the case with Ahmed. I struggled with some disagreements we had over policy, but I never struggled to convince him to have an open mind.”

On our drive back to Washington, I ask Mubarak for his assessment of the Trump presidency. He initially demurs, in diplomatic style, then says, “We value the signals sent by this administration regarding the Yemen conflict.” I raise the travel ban and ask whether Trump’s rhetoric toward immigrants and minorities—in particular toward Muslims—is doing lasting damage to America’s image in the Arab world. We cross Memorial Bridge and turn up Rock Creek Parkway, a route that takes us past all the monuments to American democracy.

“What is the American dream? It’s about America as a land of opportunity, a haven for people everywhere seeking safety,” Mubarak says. “In the end, the US is a country based on laws, on the equality of all people and all religions. This is bigger than one person.”

Yemen’s previous ambassador to Washington, Abdulwahab Abdula al-Hajjri, was a storied social animal, known for hosting nightly salons and parties at his official residence, on Glenbrook Road in DC’s tony Spring Valley neighborhood, for members of the media and diplomatic elite. Al-Hajjri held the position for 15 years, largely because he was the president’s brother-in-law. His longevity and largesse gave him outsize access to the city’s powerbrokers.

He told the Washington Post in 2011 that to fit all of his close DC friends in one place, “you’d have to have a room for 2,000, 3,000 people.” He was unapologetic about the opulence of the Glenbrook Road mansion, where he lived alone: “People understand, especially here, that a good office and good house are important for you as a diplomat. The house is not mine. It’s for the government. For any government that comes. Why would they be mad that they have a good house here?”

After his brother-in-law’s ouster, al-Hajjri announced his departure. “Stop calling me ‘Your Excellency,’ I am not anymore,” he wrote in a mass e-mail to his contacts. “That beautiful house I once occupied and used to celebrate life with all of you will now host ghosts until a new ambassador is appointed.”

Thanks to the chaos back home, those ghosts had the run of the place for three long years. When Mubarak finally arrived, he went straight to the residence. “I was shocked,” he says. The surrounding gardens had grown so thick and unkempt that the property looked like an Amazonian ruin. The basement had flooded, leaving the interior covered in mold and rot. A tattered Yemeni flag drooped on a pole in the driveway.

Mubarak considered requesting funds to renovate, but that became impossible as the country’s reserves dwindled due to war. He had more immediate concerns anyway: The embassy’s 22-person staff hadn’t been paid in months, and bills to the insurance provider were a year overdue.

He’s now receiving enough money to cover a quarter of the embassy’s operating costs and to pay employees’ salaries for three months at a time. To save money, Mubarak outsources some of the embassy’s work to contractors in Yemen, who can process data and produce public documents for a fraction of what he would pay a US firm. “We try to be as efficient as we can,” he says.

Earlier this year, the government agreed to fund renovations on the Glenbrook Road property. He estimates that completing the project will cost twice what he’s been promised, but his priority has been to make the house livable so the embassy can save on the $4,700 monthly rent he pays in McLean. Mubarak sees the restoration of the ambassadorial residence as a national imperative. He envisions a lavish space for policy discussions and dinner parties that lures many of the same administration officials he’s had to track down at the gym. It’s a way of making official DC come to him. Notwithstanding the pessimism of Washington foreign-policy graybeards, he believes Trumpworld will eventually do just that.

The embassy’s 22-person staff hadn’t been paid in months, and insurance bills were a year overdue.

“People asked me why we wouldn’t just sell it and buy another house,” he says, walking through the hollowed-out first floor on a steamy summer afternoon. “But I refused. This is part of the heritage of Yemen.”

He concedes that not everyone shares his enthusiasm. Ishraq, his wife, would prefer to stay in McLean, where Amr, 11, and Noor, 7, attend public schools. Mubarak says his three children have become “pure American” but that the transition to life in the US, at a time of roiling debate about the place of Muslims in American society, has taken a toll on Ishraq.

“It’s been difficult for her,” he says. He’s also mindful of the optics. “My people back home, they are thinking about having enough to eat, they are suffering from cholera, they are dying in war, and then they hear about someone living in DC who wants money for a house renovation! It’s difficult to convince people, isn’t it? But if we don’t do anything to this place now, we will lose in the long run.”

Mubarak is uncertain how long he’ll remain in DC and what kind of public role, if any, he will play if he returns home. The disruption caused by Trump’s election pales in comparison with the strife Yemen will face for years, probably decades. Mubarak says he reminds his children, “You will return to Yemen. We are here just for a short term.” He remains driven by the vision of building a modern democracy in his homeland. “I was part of the dream from the beginning. What I’m aiming to achieve is to get back to that point and continue this journey.”

Shortly before we leave the construction site, he recites an Islamic proverb about hard work that he’s adopted as a personal motto. He climbs into his car and then sends me a text message. The saying comes from the Hadith, the narrative of the Prophet: “Harvest for your life in this world as if you are to live eternally. And work for your hereafter as if you will die tomorrow.”

This article appears in the November 2017 issue of Washingtonian.