Sarah Forgey and I had been talking for a couple of minutes before I noticed we were standing next to Adolf Hitler. The three of us—the three-foot-high head of the Nazi dictator, the curator of the Army’s German art collection, and I—were near an enormous 1941 Hans Schmitz-Wiedenbrück painting of Wehrmacht soldiers standing heroically in the wind. Forgey and I were discussing how the Nazis used art as propaganda. The imposingly big Hitler bust, meanwhile, was bound onto a rough pine frame by some buff-colored straps, cushioned by foam. Tied up like this, the Führer seemed less than menacing. Still, you don’t really ever expect to find yourself staring at a larger-than-life sculpture of one of history’s worst mass murderers. Certainly not in an Army base off Route 1 in Woodbridge, not far from a Wegmans.

How did the Nazis’ art wind up in Virginia? It involves soldiers, lawyers, and an Indiana Jones-like professor.

This particular bust came into Uncle Sam’s possession seven decades ago. At the end of World War II, Allied soldiers seized it from the Eagle’s Nest, the Führer’s mountaintop redoubt. It was more than a simple piece of war booty. Seventy-two years after V-E Day, the Army still owns the statue as well as hundreds of other pieces of German propaganda and wartime art—all of which reside on post at Fort Belvoir. The collection includes four watercolor paintings by Hitler himself. They’re under lock and key in a flat file inside a vault.

It’s not easy to get to the Army’s Nazi-art stash. My visit took months to arrange. The Center of Military History, which oversees the Army’s art collection, does little to publicize the Nazi pieces in its possession. They’ve been loaned out only twice in the last decade. When I made this trip and finally got to the massive room that holds the artwork, an Army communications officer joked, “The Ark of the Covenant is just down there.”

Given concerns about the resurgence of far-right groups in America, the military has some reason to keep these relics of the Third Reich hidden. “There’s a very narrow line that we have to walk,” says Forgey, “because we certainly don’t want it to be a rallying point for Nazism.” Yet the roughly 600 objects housed at Fort Belvoir also provide revealing glimpses at the rise of fascism, and its folly, that have rarely seemed more relevant on this side of the Atlantic.

For all the civics-class implications, however, the story of how a cache of Nazi propaganda wound up in a Woodbridge warehouse also involves some adventure, some bureaucracy, some litigation, and some unlikely characters. It begins with a real-life Indiana Jones, a professor from Oregon who did such a thorough job of stripping Germany of propaganda after World War II that the United States has spent decades wrestling with a collection of art that few want and even fewer ever get to see.

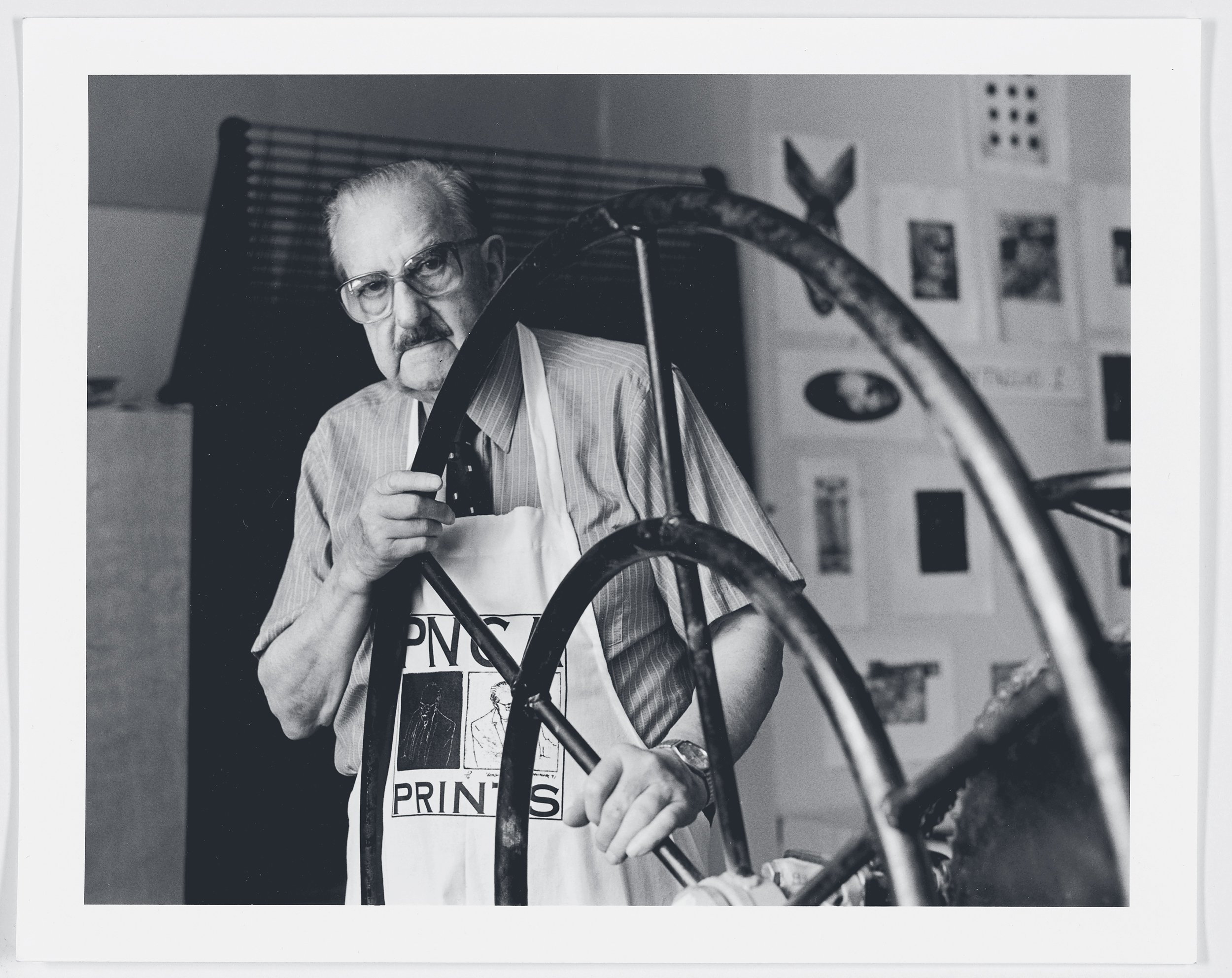

Gordon Gilkey spent much of the Second World War trying to get himself into a position to protect Europe’s treasures. The son of an Oregon rancher, he paid for his undergraduate art education by clearing land for a dollar a day. Gilkey established a relationship with Franklin D. Roosevelt after the President liked some fine-art prints Gilkey had made of the 1939 World’s Fair. After the outbreak of World War II, he lobbied Roosevelt to deploy art experts to save the continent’s masterpieces. “There should be knowledgeable people along with the troops to tell them what not to blow up,” he told FDR, according to an oral history Gilkey recorded in 1980.

“There’s a very narrow line we have to walk,” says curator Sarah Forgey. “We certainly don’t want it to be a rallying point for Nazism.”

In 1943, Roosevelt established the American Commission for the Protection and Salvage of Artistic and Historic Monuments in War Areas, with Supreme Court justice Owen J. Roberts as its chair. Some of the US art world’s most notable figures joined the commission, including Paul Sachs of the Fogg Museum at Harvard and David Finley Jr., director of the National Gallery of Art.

The commission assembled a team of Arts and Monuments officers, known as “Monuments Men,” who raced around Europe, liberating artwork the Nazis had stolen from Jewish families, churches, and museums (and laying the groundwork for a George Clooney movie 70 years in the future). Lacking the educational pedigree typical of that team, Gilkey was stuck in Texas, teaching navigation for the Army Air Corps as head of a maps, charts, and aerial-photographs division at Ellington Field.

Undeterred, Gilkey eventually got himself assigned instead to the Chief Military Historian’s office in the US European command. At war’s end, he finally got an art project of his own. He was charged with carrying out a pledge made by FDR at the Yalta Conference in early 1945: “remove all Nazi and militarist influences from public office and from the cultural and economic life of the German people.” Gilkey’s job was to oversee the seizure and removal of all militaristic artwork in defeated Germany.

Visual propaganda was central to Hitler’s rise. He had served in the German Army in World War I, and his first assignment afterward was as a propagandist. Hitler instinctively understood the appeal to the emotions of a bewildered German people whose self-image had almost collapsed in the disastrous period after that war. As he ascended to power, he advertised his National Socialist German Workers’ Party with attention-grabbing posters and symbols that forged links with the past greatness he argued Germany had lost.

As its leader, Hitler ordered the creation of a corps of artists to document the country’s military exploits. They made field sketches of German troops in action and later turned them into paintings, which were then sold to high-ranking officers and displayed in military-run museums and casinos. Other paintings depicted Hitler as half man, half god, often with medieval overtones. He bought some of the works himself, including a gigantic oil painting by Emil Scheibe that showed soldiers mobbing him at the frontlines.

As the Nazi dream crumbled in the Götterdämmerung of 1945, many of the owners of this artwork began to hide it, a logical response to the uncertainty sweeping Germany as its once-fearsome army retreated. If Hitler somehow prevailed, one could claim he was keeping the works safe from invading troops. If Germany lost, these advertisements for the old regime would at least be difficult to find.

An old man in an apron answered the door at Schloss Ringberg when Captain Gordon Gilkey knocked in 1947. His name was Wilhelm Luitpold von Bayern, and despite being dressed like a servant, he was the prince regent of Bavaria. The prince had been polishing his collection of toy cannons when the US Army appeared. Gilkey advised him he was there to inspect a collection of war art he’d heard was in the castle. The prince let him in and—after Gilkey determined that the art had indeed been previously held by a Luftwaffe command—supervised as soldiers loaded the paintings onto trucks.

This was a relatively easy transaction. The soldiers “must be thirsty,” the prince said when they were done, and he summoned the castle’s artist in residence with a handclap, then poured them all beer from a tap on the castle’s wall.

Other Gilkey capers weren’t so frictionless. Once, after he traced some of Hitler’s own collection of war art to a bar in St. Agatha, Austria, the manager refused him entry. Gilkey’s companion, an Army captain from Texas, threatened to shoot down the door—as well as the manager if she stood in their way much longer. The conductor of the Vienna Symphony Orchestra happened by, intervened, and finessed the situation. (Not only did the Army get the paintings, but the Texan got a date with the conductor’s daughter.)

During his assignment, Gilkey found war paintings hidden in salt bins at Bad Aussee, Austria, where Hitler and his cronies had also stored famous works stolen from all over Europe. He turned up works in a train bound for Berlin that American planes had strafed but miraculously hadn’t burned. He found a stash in a woodcutter’s hut near the Czechoslovakian border. In that case, the paintings were hidden under floorboards in the attic. They’d nearly been torched when, two days before Germany surrendered, some Luftwaffe men holed up there with “food, drinks, and fräuleins,” as Gilkey described in a 1947 report. It would have been a self-inflicted wound by the Germans: Some SS men who’d been among Hitler’s personal bodyguards happened upon the party and, convinced they’d come across American troops, began shooting. “A battle of mutual extermination resulted before the error was discovered,” Gilkey wrote.

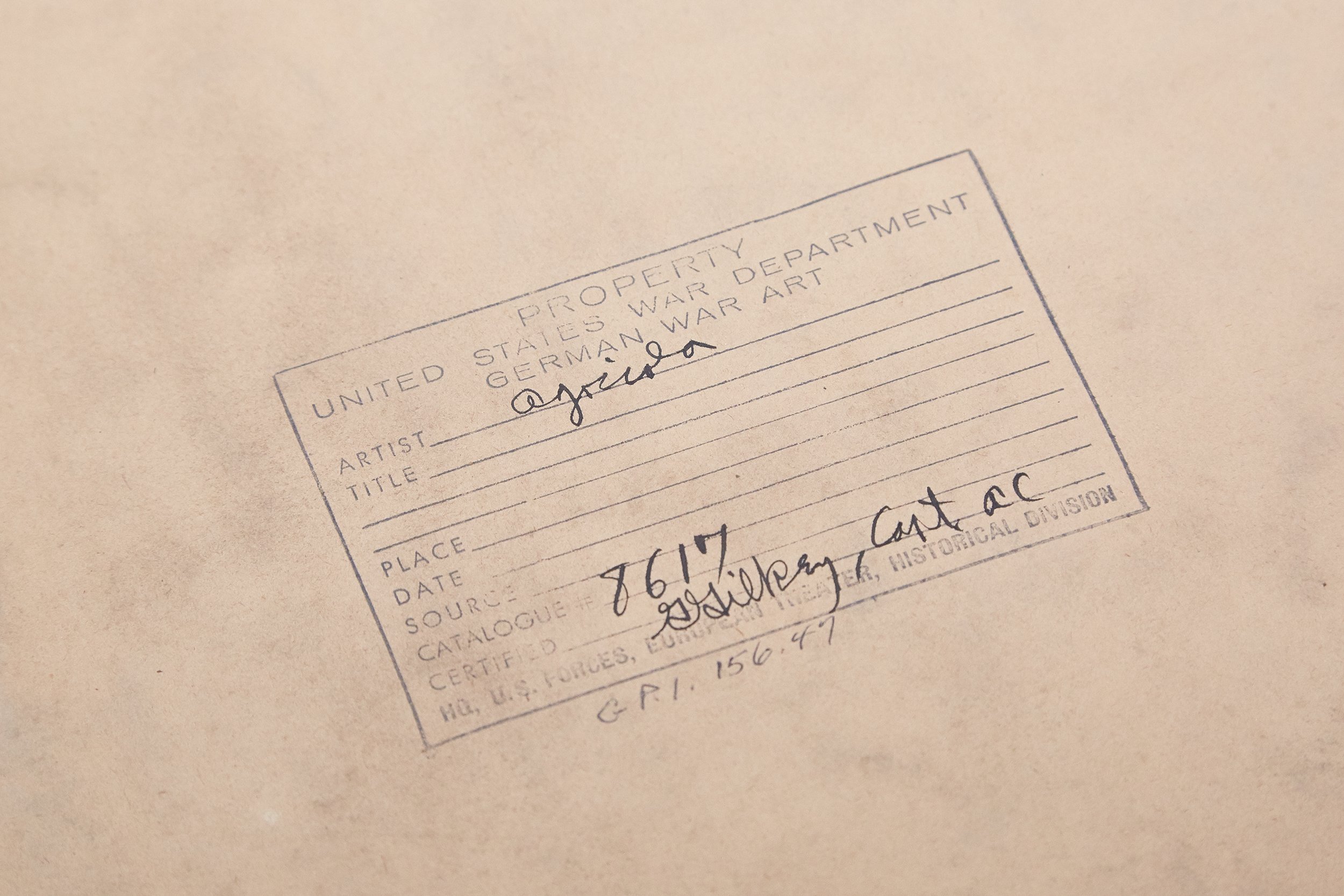

When he got there, the artworks were mildewed and a family of mice had moved in and “eaten the ends off many pictures,” leaving them with “an uneven deckle edge.” Gilkey oversaw the restoration before crating them for shipment to the US. He affixed a label to the back of each work and initialed every one.

All in all, Gilkey’s team wound up confiscating 8,722 pieces of art. But whereas the higher-ups who had blessed the mission might have imagined that the haul would be entirely made up of master-race propaganda and fascist hate-mongering, the crates that were shipped back to Washington in March 1947 contained an awful lot of relatively anodyne stuff—so anodyne, in fact, that Gilkey was willing to hold a small exhibition in US-occupied Frankfurt just before packing the stuff up. So anodyne that, inevitably, the owners and artists were unafraid to say they wanted them back.

The debate over what to do with Gilkey’s haul was just getting started. But as the decades progressed, the debate would encompass not just the accidentally confiscated still-lifes but the fascist core of the collection, too.

It was money—the need to eke out a living in war-ravaged Germany—that led to the first pleas. Artists and their families, desperate for cash, petitioned the US government for the return of individual works. One of them, Herbert Agricola, copped to having painted some militaristic art, including depictions of hangings, but noted that he also had painted landscapes and portraits.

“I think there must be a way to select at least the number of paintings which do not show any military stuff,” he wrote in 1948, saying he was “in a real bad situation now.”

Eve Zimmerman, widow of the deceased graphic artist Bodo Zimmerman, wrote that she had “only a little hope” of receiving her husband’s works, which if returned would not only help the family stave off financial ruin but also would “tear him away from oblivion.”

In 1950, the US returned 1,659 pieces to West Germany that it deemed neither militaristic nor political. But there was a problem: The country didn’t want them. The postwar government “didn’t want to have anything to do with the Nazi programs of World War II,” wrote art historian Bess Hormats, who was acting curator of the Army’s art collection. So even after being shipped, the repatriated artwork languished in a warehouse in Bonn until the late 1970s, after a German TV documentary and symposium generated public pressure on the West German government to bring the works home.

By that point, historians were wondering whether even overtly fascist works were all that harmful. In a 1978 Washington Post article, Hormats wrote, “The relatively few works which can be considered Nazi propaganda paintings, only one generation after they were created for the Thousand Year Reich, appear so pompous and ludicrous that they are laughable to all but the lunatic fringe.”

American politicians largely accepted Hormats’s assessment. In 1981, Congressman G. William Whitehurst of Virginia introduced legislation to repatriate all of the German art in US possession. President Ronald Reagan signed the bill the next year.

Still, not all of the art went back. The Army decided that while a lot could go, pieces showing swastikas or celebrations of dead Nazi leaders would have to remain. Much of the collection ended up at Berlin’s Deutsches Historisches Museum. The US kept 586 pieces of the most heinous stuff. But just because it was heinous didn’t mean no one wanted it. Thus a rich Texan named Billy F. Price introduced a new problem.

Price had become rich manufacturing compressors in Houston, a career that allowed him to indulge a fascination in Hitler’s paintings. He self-published a survey of the dictator’s paintings called Adolf Hitler: The Unknown Artist. He also befriended the heirs of Hitler’s photographer, Heinrich Hoffman, who accused the US of wrongly seizing not only Hoffman’s photographic collection—some of which ended up in the National Archives—but also four paintings by Hitler that Hoffman said he’d purchased himself or had been given as gifts. Hoffman died in 1957, and in 1982 Price sued the government, saying he’d bought the rights to these works from Hoffman’s heirs and would like everything back.

Price’s legal theory was “basically that it was stolen,” says Larry Campagna, a Texas lawyer who worked on the case. “It is possible during wartime for an occupying army to make use of your property and sometimes to even requisition your property. If you need somebody’s house, you don’t keep title to the house.” The main argument was, he says, that “it was the family’s property and they never lost title to that.”

Price convinced a Texas district court, which in 1989 ordered the US government to turn over the artworks to Price and to pay a nearly $8-million judgment. The United States appealed. In 2003, a federal judge in DC reversed the ruling and dismissed the case. Price died in 2016. Hitler’s paintings remained in the Army’s hands.

It’s not quite like storming Schloss Ringberg, but getting in to see what remains of the Gilkey collection poses challenges. It involves making your way through a security gate, then driving almost a mile before arriving at what looks like a 1980s elementary school that has possibly the cleanest loading dock in America. This is Fort Belvoir’s state-of-the-art Museum Support Center, where the government houses the artifacts that tell the story of the US Army’s 240-plus years. Visitors to its cavernous interior are brushed by positive-pressure air and illuminated by UV lights that control microbial growth. It holds General John “Blackjack” Pershing’s car, a priceless Revolutionary War flag, some original Norman Rockwells, and Abner Doubleday’s sword. When people from the Smithsonian visit, Sarah Forgey says, “they’re jealous.”

Forgey has worked for the Center of Military History for ten years, the first two as a contractor. She became an expert on the German war art by reading everything she could find about it. But she’s also able to look at the art critically, discussing a question that likely few art historians would prefer to tackle: Was Hitler any good as a painter?

The subject comes up after Forgey sweeps a sheet of foam wrap off a folding table. Underneath are four paintings in gilt frames whose author also created the Holocaust.

In 1950, the U.S. sent back 1,659 pieces it deemed harmless. One problem: The German government didn’t want them.

They’re small. One shows World War I soldiers in a valley. Another shows a Belgian town, around the same time, turned to rubble by artillery. We linger on a painting Hitler made of the courtyard in Munich’s Alter Hof. He portrays it as empty of people, a trickling fountain the only sign it wasn’t abandoned.

“In terms of his draftsmanship, he’s proficient,” Forgey says. “You know, if I took an art class, I’d be happy with the results if I painted that.” But, she says, “I find personally that the more you look at these, the creepier they get.” Perhaps that comes from knowing who painted them, she allows, but “the more I look at this, the less life I see.”

When Hitler depicts humans, they’re tiny, inconsequential, compared with the buildings or landscapes he places them in. Yet neither a tree in the corner nor the water in the fountain shows any “sparkle of life,” Forgey observes. The shadows are pale and play ominously, edging inward from the painting’s edges. “It just looks creepy to me after I’ve been looking at it for a while.”

In 2019, the Army will open the vast National Museum of the United States Army in Fort Belvoir, but it’s unclear whether much of the Nazi collection will see the light of day. Though civilian researchers can ask for a visit, the Army is pretty careful about who’s allowed in, and every now and then it gets an inquiry from someone who “raises a red flag,” Forgey says.

Gilkey died in 2000, having spent a career in academia, rising to dean of liberal arts at Oregon State University, where he donated more than 10,000 prints he’d collected over the years. Forgey says it’s not unthinkable that the Army might at some point show some of the darker works he acquired: “I’ve believed that this material can be interpreted in an educational exhibit, and you know it is for the good of the country that we see it.”

That seems to have been on Gilkey’s mind, too. Even as he swiped paintings from all over the Reich, he was thinking about preserving them, noting in his report that he was thrilled to find art supplies from Hitler’s war-art program for sale in a black market in Passau. “Seldom do retouchers have available the same pigments with which the original paintings were made,” he wrote.

Even after the army deaccessioned most of the stuff, a good percentage of what remains isn’t, strictly speaking, propaganda but rather wartime scenes that the US kept as part of its “study collection.” As one striking example, Forgey shows me drawings of the Battle of Monte Cassino from Axis and Allied perspectives.

It’s still the propaganda, though, that shows how easily everyday life can turn dark. A chilling Fritz Erler triptych depicts stylized Germans—a farmer, a professional type—among soldiers recast as Roman warriors. The central panel shows a rally with thousands of hands raised in salute to an empty stage bedecked with a Nazi banner. Another work I’d been hoping to see was out for restoration when I visited: a large piece of plywood called “The Standard Bearer” that fashions Hitler as a medieval knight. “This is the heart of Nazi propaganda right here,” Forgey says. At one point, an American GI had made a bayonet hole in Hitler’s face, which Gilkey catalogued as a “Third Army deletion.” Says Forgey: “We consider it to be part of the painting’s history.”

How dangerous is this stuff now? At a time when Richard Spencer led a DC crowd in Nazi salutes while shouting, “Heil, Trump!” and when young men carrying swastika flags swarmed Charlottesville shouting about Jews, it’s not crazy to believe there’s a dangerously enthusiastic audience for these works in real life. Bess Hormats’s Cold War conviction that these pieces were laughable feels a little less persuasive today.

I’m not comfortable with the government deciding to quarantine any expression, but when Nazism—actual Nazism!—is again gaining prominence in the US, you don’t have to stare long at a depiction of Hitler at an early Nazi meeting called “In the Beginning Was the Word” before wondering whether modern-day Germany got it right by banning this garbage. How much smarter are we, really, than the people who followed Hitler into the abyss? As Gilkey wrote in his 1947 report, “German art became a tool to spread the manure of Nazism.”

Back at Fort Belvoir, many of the paintings in the German war-art collection hang on screens that roll out from a large, pergola-like steel frame. They share the rack with the work of American artists who documented military life in its peaceful and most God-awful moments, from a painting of soldiers on leave in an English park to Tom Lea’s “The Price,” which shows a Marine on Peleliu seconds before his death, his left arm, shoulder, and chest pulped by mortar fire. “Our artists were given an astounding degree of autonomy,” Forgey says.

The German war artists didn’t get that kind of freedom, but glimpses of the real story of the war—events propaganda could never accurately portray—managed to sneak in past the censors’ eyes. One canvas shows soldiers in a trench holding grenades, unsure of what fate would greet them over the top. Another depicts a miserable march through a winter landscape with a dead horse mostly out of the frame.

Time has made some of the works’ own history even harder to see. That Hitler bust has a dent in it from when it fell and ever-fainter wax marks from boots where US soldiers kicked it. Using a black light, you can see an obscene drawing on one side of his head. On the other, a soldier wrote: “FOOL.”

This article appears in the November 2017 issue of Washingtonian.

Correction: This article originally referred incorrectly to the location of the Eagle’s Nest. It is located in Bavaria, not Austria.