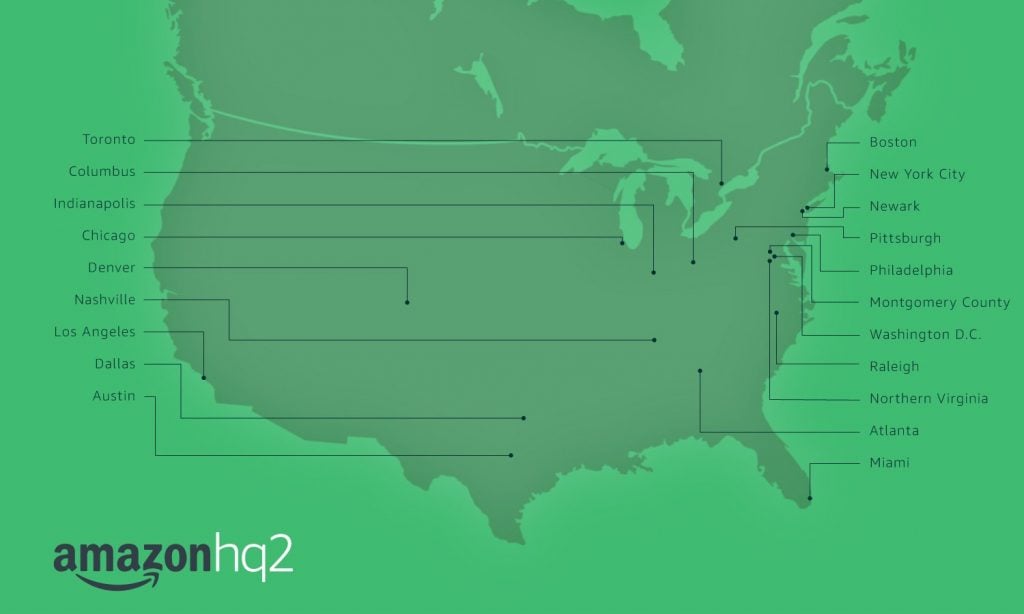

The current trend in the obsession about Amazon and its second headquarters project is mostly blind suggestion that despite the 20-location shortlist the commerce and web services giant released last week, the Washington region is a lock to get it. The apparent evidence is plentiful. Three distinct jurisdictions in the area—the District, Montgomery County, and amorphously designed Northern Virginia—made the cut; Amazon chief executive Jeff Bezos owns the Washington Post (and a Kalorama mansion to boot); the company’s cloud-computing division has a large local footprint.

Columnists for Bloomberg, Slate, CNBC, and USA Today, to name a few, all seem to think that’s enough. Perhaps they’re correct in guessing that Amazon will follow its boss’s extracurricular pursuits and build up in Washington. Those 50,000 new jobs, millions of square feet in new commercial development, and $5 billion in direct economic impact are all but ours, already, right? Then again, Amazon’s also scouting for a 1 million-square-foot lease in Boston, another finalist city. But if Amazon considers the housing costs that future employees at its non-Seattle base face—as the real-estate research service Trulia suggests—then Chicago, Pittsburgh, and Columbus, Ohio are in the mix. At a recent dinner, a Philadelphia resident told me that Amazon might be drawn there because it’d be a logical neighbor (or eventual slayer) of television juggernaut Comcast. (As it happens, those two firms just entered a “strategic relationship” in which Comcast will increase its dependency on Amazon Web Services.) Paddy Power, the Irish betting website, will give you 2-to-1 odds on Boston, 5-to-1 on Atlanta, and an 11-to-2 payoff on Austin, Texas. (The District is a fourth-place straggler at 8-to-1.) Nashville, Tennessee is a “dark horse!” Toronto will win because President Trump dislikes immigrants. Miami’s a front-runner because it’ll give Bezos an unlimited supply of Pitbull.

Okay, that last one is a Saturday Night Live sketch. But it’s not hard to find a column, economic study, anecdotal conversation, or bookie making a case for any of the 20 locations Amazon says it’s considering for HQ2, as the company’s future project is known.

It’s fun to guess where Amazon will go. It’s not unlike the process we went through a few years ago over the 2024 Summer Olympics. Back in 2015, organizers for Washington’s bid thought they were goosing their chances when the city hosting a conference of Olympic officials from around the world. It didn’t do much good, as the US Olympic Committee wound up going with Boston, then Los Angeles after its first choice bailed; best of luck to Southern California circa 2028. (Global skittishness about hosting the Olympics resulted in LA waiting another cycle in favor of Paris.)

Of course, there’s a huge difference between a roving, quadrennial sports event with a track record of wrecking its host cities and one of the world’s largest companies building a presumably permanent facility full of high-skilled, high-income professionals. But even with all the tea leaves coming from Bezos’s holdings, Amazon’s real-estate inquiries, and various economic studies, we’re still very much stuck in conjecture mode about HQ2.

Unfortunately, the guessing game is also just about all there is to do right now, thanks a mostly united front of opacity from local officials who are pursuing HQ2 on behalf of their cities, counties, or states. The latest blockade comes from the Loudoun County Department of Economic Development, which this week rejected Washingtonian‘s request, filed under Virginia’s Freedom of Information Act, for any information on the bid it’s sharing with Fairfax County. Not how much the county spent on making its pitch, where it suggests Amazon might build, and certainly not the economic incentives—that the company has said will be “significant factors” in its ultimate decision—it’s putting on the table. Arlington County, believed to be the other Northern Virginia proposal Amazon’s considering, hasn’t replied to a similar request.

DC and Maryland look like open books, comparatively, though in reality they are far from that. Thanks to one FOIA request delivered in December, city residents learned that Mayor Muriel Bowser’s office paid a marketing firm nearly $140,000 to design and promote its bid to Amazon. But the documents the city produced, while full of colorful renderings of where the District would put HQ2, were carefully redacted to remove any references to financial incentives. Only later, after repeated prodding from WAMU, did the city release a version of its proposal with information about its offered incentives. If Amazon moves into the city limits, it’ll get, among other kickbacks, a five-year tax holiday, and credits of up to $7,500 for each high-skilled worker hired. Up the road, Montgomery County had been about as withholding as its Virginia neighbors, with the only big reveal being that the former White Flint Mall site in Bethesda was floated as a potential HQ2 location.

Once Montgomery County made the first cut, though, Maryland Governor Larry Hogan was ready to go public with his offer. The state will give Amazon up to $5 billion in economic incentives spread across income- and property-tax credits—and even a sales-tax exemption for expenditures during construction—over 17 years. Hogan’s even got a clever name for the legislation that’ll carry his incentive package: the Promoting ext-Raordinary Innovation in Maryland’s Economy (aka, “PRIME”) Act.

But it shouldn’t take getting to the bake-off stage to get officials to open up about what they’re prepared to throw at Amazon. Since the request for proposals on HQ2 first went out, the process has resembled a tug-of-war between governments trying to impress Amazon publicly with razzle-dazzle like props and dopey videos starring mayors, and inquiries from reporters and other interested parties about what the real offers. There have been a few successes, notably Chicago, where a FOIA request revealed a plan to let Amazon recoup $1.32 billion in an “income-tax diversion”—in other words, letting the company hold on to its workers’ tax payments that would otherwise be submitted to city and state coffers.

For the most part, though, there’s been minimal transparency on HQ2 by design. Economic development officials say its to protect their jurisdictions’ competitive edges. Loudoun County, in its rejection letter, told me that disclosing anything about its bid would “adversely affect the financial interest of the public body.” Clearly, though, this isn’t a blanket rule everywhere. It took getting on the short list, but Hogan’s made public how much he wants Maryland taxpayers to foot if Montgomery County is the big winner. New Jersey was a model of relative openness last year when US Senator Cory Booker and then-Governor Chris Christie made their $7 billion offer. And Pennsylvania’s office of open records just ruled that Pittsburgh’s proposal is a public document under state law and can be released.

Perhaps that ruling, barring Pittsburgh’s appeal, will set a model. Amazon’s language in its RFP made clear its intentions that it expects a big welcoming gift from whatever lucky city or county it picks. It would seem logical that whoever lives there might want to know what they’re giving. Without that information, we’re left with a very clumsy guessing game.