The home phone of FBI special agent Michael Rochford rang in the middle of the night on August 2, 1985. He grabbed it and heard the voice of his FBI supervisor. “There’s a plane coming in, a high-level defector.” The day before, a Soviet man had walked into the US consulate in Rome. He had told American officials he was a colonel in the KGB and wanted to defect to the United States. The man promised to reveal Soviet secrets in exchange for a new life in the West. Now his plane was scheduled to land at Andrews Air Force Base. Rochford’s supervisor instructed him to go to the air base, meet a CIA analyst named Aldrich Ames, and find out what this defector knew.

Rochford was a young agent, 30 years old, with a working knowledge of Russian. After arriving at Andrews, he discovered that the defector’s plane had already landed and that Ames had whisked him away to a CIA safe house in Oakton. When Rochford arrived there, he found Ames, a thin man with oversize glasses and a bushy mustache who worked on the CIA’s Soviet desk. Ames was chatting with another man who looked to be in his late forties or early fifties. He had blond hair, a handlebar mustache, and an athletic build, though he wasn’t overly tall. A scar was visible on his right hand.

The man’s name was Colonel Vitaly Yurchenko, of the KGB. American intelligence officers had already started debriefing him using a tape recorder. He didn’t need much prompting. In a gush of Russian-accented English, the KGB colonel began to blurt out a number of astonishing Soviet secrets. The only problem for the Americans was slowing him down. After two or three hours of listening to Yurchenko, they decided to take a break. They went down to the basement and huddled together, heads buzzing.

For months, the Americans had suspected there might be a KGB mole inside one of their intelligence agencies. That would have explained several baffling events, particularly the sudden arrest two months earlier of the CIA’s most valuable spy in the Soviet Union, an aviation specialist named Adolf Tolkachev. In those first two or three hours in the Virginia safe house, Yurchenko revealed the existence of not one but two traitors, American intelligence officers who were stealing US secrets for the KGB. He said he didn’t know their names, but he gave the debriefers enough information to start hunting. One mole, he said, was a CIA analyst—a man the KGB called “Mr. Robert.” The other was an employee with the National Security Agency, the organization that intercepts and reads foreign communications.

With these revelations, Yurchenko sparked a chain of events around the world. Traitors were exposed, propaganda campaigns devised and launched, secrets whispered to the press, careers altered and destroyed. Moles, leaks, dirty tricks, “active measures”—it was a moment that exposed America’s vulnerability to Russian espionage. The year 1985 came to be known as the Year of the Spy. It also taught a painful and timeless set of lessons—ones that transformed the careers of intelligence professionals like Michael Rochford, whose eyes were forever opened to the penetrations of Russia and the KGB.

But as proven by Russia’s brazen and successful attack on our 2016 election, the lessons of the Year of the Spy were ones most Americans forgot.

CIA analyst Colin Thompson arrived at the Oakton safe house on the second day of the Yurchenko debriefing, joining Aldrich Ames and Michael Rochford. When Ames took on a new assignment, Thompson became Yurchenko’s primary CIA handler. Having served in Vietnam for the CIA, Thompson examined the KGB colonel with a practiced eye. “He plans well, he’s careful, he’s clever,” Thompson told me recently. “You see the same sort of things, oddly enough, reflected in Putin these days.”

Unsure at first if Yurchenko was telling the truth or lying, the Americans engaged him in hours of intense conversation, mostly in English, with some swatches in Russian, day after day. At times, the FBI interviewed him alone, without the CIA guys there; at times it was the other way around; and at times they all interviewed him together. The debriefers often asked Yurchenko questions to which they already knew the answers, as a test of his knowledge and accuracy.

They asked him to prove his KGB bona fides, to describe his career path in detail. In his youth, Yurchenko had served in the Soviet navy, where he’d gotten the scar on his right hand, in a winch accident. Then in the mid-1970s, he’d joined the KGB as a security officer at its Washington headquarters, known as the Rezidentura, located on the upper floor of the Soviet Embassy on 16th Street, a building that housed about 100 Soviet officials and staffers, 40 of whom were KGB spies and staffers. He worked there several years until he was transferred home to Moscow in 1983. Though he never reached the KGB’s highest levels, his connections gave him access to cables, gossip, and deep secrets.

The debriefing sessions were audiotaped. Rochford took the tapes home each night, transcribed them, and circulated the transcripts within the FBI, where agents checked Yurchenko’s claims against available information. The defector passed these tests. “Everything that he gave us was verifiable from other sources,” Rochford recalls. “And the new stuff was startling.”

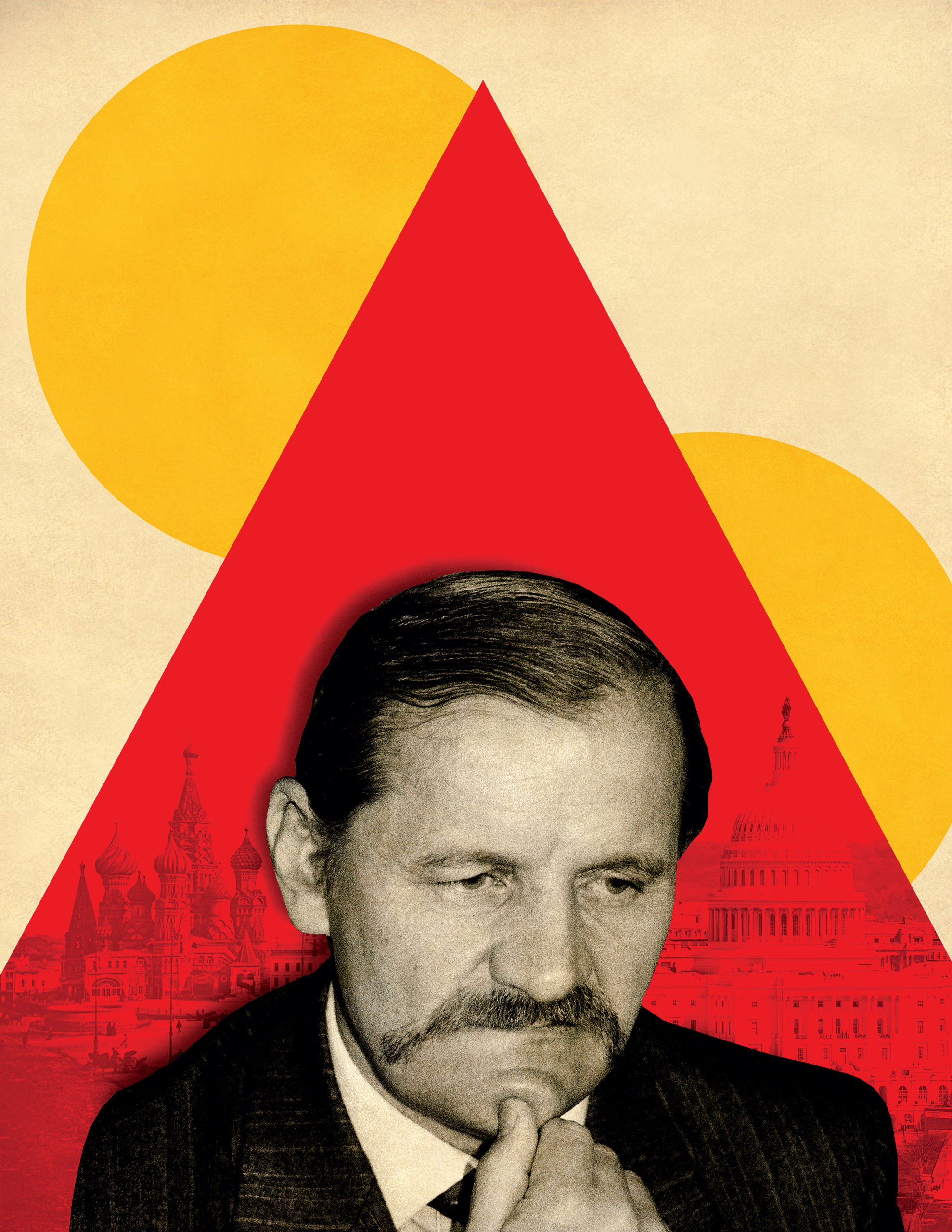

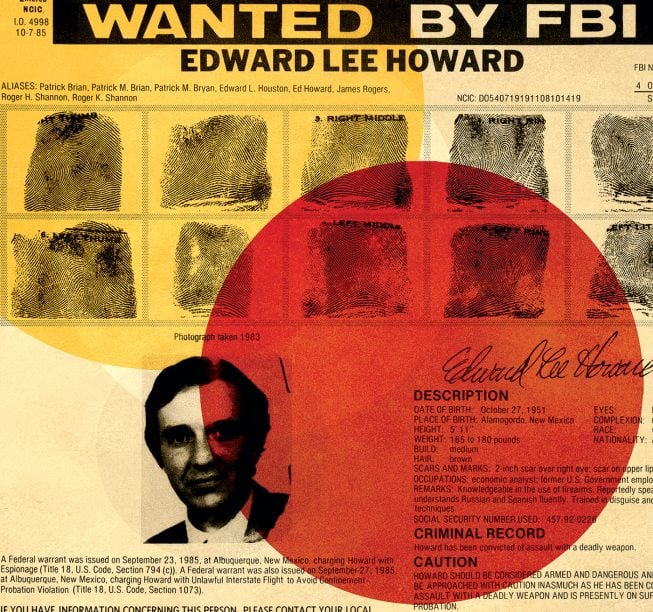

All in all, Yurchenko revealed important details about 55 to 60 KGB assets in America. The FBI knew about some of these assets already—Yurchenko added new information to the case files—and some were completely new. The biggest involved a KGB mole inside the CIA, the man called “Mr. Robert” in KGB cables. Based on Yurchenko’s description of him, Americans suspected that Mr. Robert was Edward Lee Howard, a CIA officer who worked on the Agency’s Soviet desk between 1982 and 1983. A drunk and a gun enthusiast, he had failed four CIA lie-detector tests and was ultimately fired.

Following up on Yurchenko’s tip, the FBI dispatched agents to confront Howard in Texas. He denied he had ever worked for the KGB—then fled. (To the embarrassment of the FBI, Howard managed to slip away from the agents who were monitoring him, made it to an airport, and escaped to Moscow, where he lived under asylum until his death in 2002.)

The second mole identified by Yurchenko was an NSA analyst who had warned the KGB in the past about a US program to intercept Soviet communications, an elaborate and costly effort code-named Ivy Bells. Starting in the early 1970s, US agencies had installed a series of wiretaps on undersea communications cables used by the Soviets, an effort that involved sending US submarines and deep-sea divers into frigid Soviet waters. Around 1980, the Soviets discovered and destroyed the Ivy Bells wiretaps. Now the Americans knew why: An NSA mole had betrayed the program.

Yurchenko’s energy flowed for weeks in the safe-house debriefings. He kept a yellow pad beside his bed and would jump up in the night and write down something he wanted to tell the Americans in the morning. Between debriefing sessions, he dropped hints about why he’d taken the drastic step of defecting. He said the things the Americans expected to hear—he no longer believed in Communism, he thought the KGB was corrupt—but his main motivation seemed more personal.

There was nothing keeping him in the Soviet Union, he said. He had a wife he didn’t love and a troubled 16-year-old son. His mother had recently died of stomach cancer. He had cancer, too, the same kind that had killed his mother, he told them. It was terminal—he didn’t have long to live. One day, chatting with Yurchenko in the kitchen, Rochford noticed he hadn’t brought a change of shoes to America, suggesting that the colonel had left abruptly, without a plan, perhaps on impulse.

In exchange for his cooperation, Yurchenko made two key demands: money and anonymity. He asked the Americans to keep his defection secret, explaining that as long as the Soviet legal system couldn’t prove he was a traitor, the KGB wouldn’t retaliate against the wife and son he’d left behind. The Americans agreed and also promised him a steady income and free health care for life if he stayed. It seemed like a reasonable deal.

“I really liked Yurchenko,” Rochford says. “My sense is that he was a very open, opinionated, experienced person who really wanted to get the details correct. . . . I didn’t look at his selfish motives or anything else. I didn’t care. I said, this is a source; he was friendly. And in a strange sort of way, he liked to kind of teach. He was trying to teach us about the KGB.”

For instance, Yurchenko explained to the Americans how the KGB engineered campaigns of blackmail and propaganda—“active measures”—to influence elections and public opinion in many countries. It had agents of influence all over, people who could dig up smut on politicians and plant false news stories, always with the goal of weakening the Glaviny Vrag, the Main Enemy, which in the KGB mindset equaled the United States.

“It was an eye-opener for me,” Rochford says. “It was ‘Oh, wow. These guys, they have a big plan. They’re patient.’ ”

Yurchenko even told the Americans how the KGB dealt with defectors to the West. According to Yurchenko, the KGB often tried to get defectors to change their minds—to re-defect. A re-defection was valuable to the KGB because it cast doubt on the integrity of any future defectors: A defector should never be trusted, because he may be a false one.

Defection is one of the hugest gambles a person can make. It’s a blind leap across a border that closes forever behind you. Some defectors never adjust to living in the custody of a foreign government. The stress and loneliness are too much. “A lot of them came expecting something that never happened,” Thompson says. “By defecting, they would solve the problems that they left behind. Well, it doesn’t work that way, either. You don’t leave your problems on the other side of the border. They come with you.”

After a month of divulging secrets to his American handlers, Yurchenko soured. The initial high was gone. He was no longer waking up in the middle of the night eager to jot notes on the yellow pad. He was picky about his food, refusing to eat anything with the slightest bit of spice, on account of his stomach cancer. He boiled plain chicken breasts in a pot in the safe house’s kitchen. At Yurchenko’s request, the FBI sent someone to a Russian pharmacy in Brooklyn to buy a certain kind of herbal stomach remedy—little black seeds that Yurchenko carried around with him in a pouch and ate with his meals. But then he complained he was lonely.

Colin Thompson and Milton Bearden, a 20-year veteran of the CIA’s clandestine services and deputy chief of the Soviet division at the time, reasoned that Yurchenko might be missing female companionship, but Yurchenko wasn’t interested in meeting women. Instead, he seemed hung up on one particular woman, his mistress from the late 1970s, when he was stationed in Washington—a Soviet pediatrician named Valentina Yereskovsky. She was now living in Montreal with her husband, a Soviet diplomat. Yurchenko said he wanted to go to Canada and bring Yereskovsky back to America. His dream was “to live in some relatively remote area of the United States with a Russian-speaking woman who could take care of him,” says Thompson. “Live out his days, not in splendor but in comfortable isolation, as a Russian as opposed to a Soviet.”

The Americans went out of their way to cheer up Yurchenko, an effort that involved two of the more surreal episodes of the Cold War. First, they tried to reunite Yurchenko with his former mistress. In late September, the CIA brought Yurchenko to Montreal and worked with Canadian intelligence to bring Yurchenko to his lover’s front door. The CIA was prepared to offer asylum to Yereskovsky—everything had been arranged to whisk her back to the United States on the spot and process her as a defector. But instead of embracing Yurchenko when he came knocking, she called him a traitor and shut the door in his face.

Rochford recalls: “She looked at him and said, ‘Hey, loser, you’re a defector now. It was fun at the time, but I’m not going to leave my husband and my kids.’ Typical man, right? We’re all f—in’ wrong. It was the saddest part of the debriefing.”

Things got even worse for Yurchenko. One day in Montreal, the KGB colonel picked up a newspaper and noticed a story about how the CIA had just bagged a big Soviet defector. Someone had leaked the details of Yurchenko’s case (though not his exact name) to the press. The agents suspected that the leak may have come directly from CIA director William Casey. Yurchenko was livid. “You’ve betrayed me and my family,” he told Colin Thompson.

Desperate to keep Yurchenko cooperative, the Americans conceived an even more outlandish plan: a two-week dude road trip through the Southwest. They flew from Washington to Phoenix, six men in all—Thompson of the CIA, Rochford and a fellow FBI agent, two security guards, and Yurchenko. The idea was to get Yurchenko out of the usual safe-house routine, into space, moving through the country, and, if necessary, to find him a woman. Bearden told one of the guards, “If there’s a need to get this guy laid, for goodness’ sakes, get him laid.”

A Russian mole at the CIA was known as “Mr. Robert.”

Early on, the men developed a genuine camaraderie. In Phoenix, they rented two cars and drove north, wearing civilian clothes, Yurchenko in a pair of chinos and a checked shirt. With his elegant handlebar mustache, he didn’t exactly look like a corn-fed American, but he blended in well enough, at least until he had to order food and his Russian accent emerged. He asked for oatmeal one morning at a diner. The waitress didn’t follow. Huut-meal, he repeated in frustration. Huut-meal.

The Americans took him to see the spectacular Hopi ruins east of Flagstaff, 1,000-year-old caves chiseled into the hills, and introduced him to the game of golf near Scottsdale, where they played a round at a desert resort, the sun setting behind the red hills as the group walked up the final fairway. They drove to the Grand Canyon, which impressed Yurchenko (“He kept saying, ‘We have lovely places, too, but they’ve been defaced with graffiti and stuff,’ ” Thompson recalls), and north through the red-rock formations of Utah (Yurchenko picked up a handful of rocks and gave one to each of the Americans as a gift, saying it meant they were all on the same team).

They took him, briefly, to Las Vegas and offered to procure a prostitute from Mabel’s Whorehouse, a legal brothel. Yurchenko declined. He was more interested in exploring Mormonism—he had heard about the religion somewhere, its customs and temples. So the Americans drove him to a Mormon temple in St. George, Utah. “I think he was looking for something to hang onto,” Thompson says. “He didn’t really know what he wanted to do. He was trying to figure it out.”

Toward the end of the trip, the Americans got word from Washington that some intel guys were flying out to Lake Powell, near Hoover Dam. They needed to talk with Yurchenko about the NSA mole. The men took Yurchenko to Lake Powell, where they showed him a photo array of suspects. Yurchenko pointed to the picture of a 44-year-old former NSA computer analyst named Ronald Pelton. The following month, Pelton was arrested. (He was later sentenced to life in prison but released in 2015.)

Rooting out Pelton was a moment of elation for the Americans: The long weeks of debriefings had paid off, and a second KGB mole had been identified and neutralized. But it marked a point of no return for Yurchenko. The Americans told him he might be required to testify in court, thereby exposing himself as a KGB traitor. The group flew back to Virginia, where Bearden gave Yurchenko another piece of news: The CIA’s physicians had determined that Yurchenko’s stomach pains were caused not by cancer but by a minor bowel disorder. It was treatable. To Bearden’s confusion, though, the spy seemed crushed.

“He had this fatalist Russian attitude: Oh, I’m going to die, so I’ll make the world right,” Rochford says. “And [when] he realized he wasn’t going to die, he just went: Oh, shit.”

Former CIA officer Edward Lee Howard, a.k.a. Mr. Robert, fled to Moscow after his identity was revealed by Yurchenko. He died in 2002.

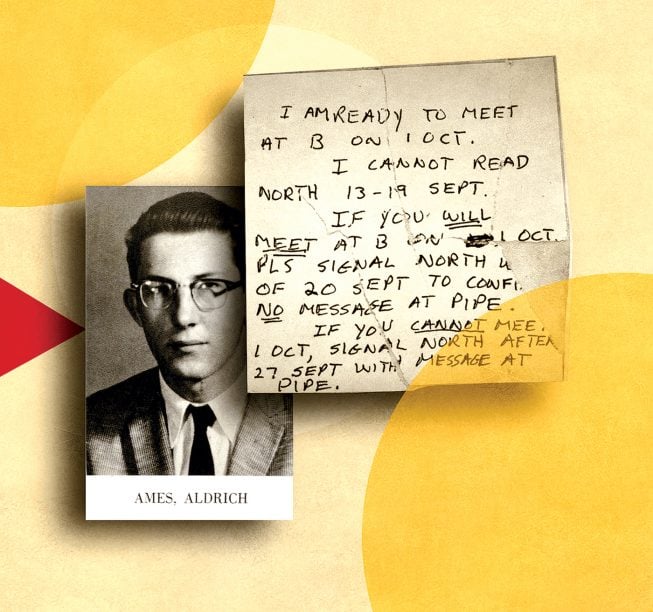

Former CIA officer Edward Lee Howard, a.k.a. Mr. Robert, fled to Moscow after his identity was revealed by Yurchenko. He died in 2002. KGB mole Aldrich Ames fed the Soviets details of the CIA’s interrogations of Yurchenko. He was convicted of espionage in 1994.

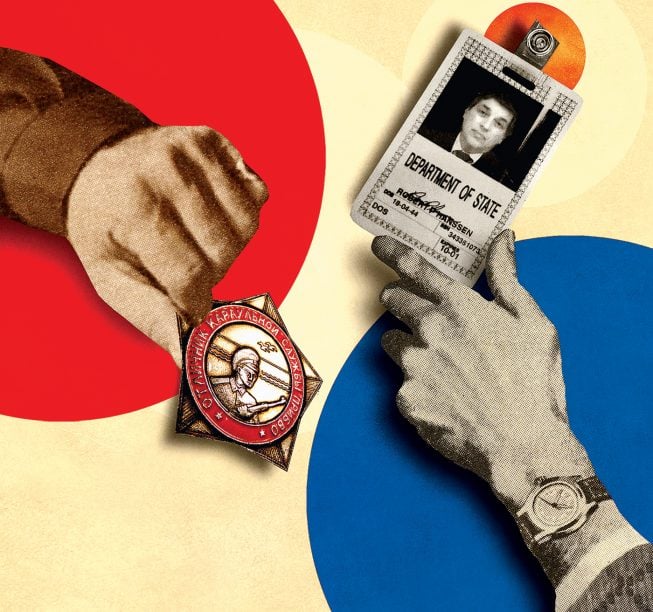

KGB mole Aldrich Ames fed the Soviets details of the CIA’s interrogations of Yurchenko. He was convicted of espionage in 1994. Yurchenko helped expose former NSA analyst Ronald Pelton for giving secrets to the Russians. Arrested in 1985, he was released in 2015.

Yurchenko helped expose former NSA analyst Ronald Pelton for giving secrets to the Russians. Arrested in 1985, he was released in 2015. FBI agent Robert Hanssen was an active spy for the Soviets during the Yurchenko case. He’s serving 15 life sentences in a maximum-security prison.

FBI agent Robert Hanssen was an active spy for the Soviets during the Yurchenko case. He’s serving 15 life sentences in a maximum-security prison.One of the Soviet Union’s most effective spymasters during the Cold War was Oleg Kalugin, a KGB major general, the youngest man ever to attain that rank. At the peak of his career, Kalugin commanded all Soviet counterintelligence operations around the world and was in charge of propaganda efforts against the United States. Among the hundreds of his underlings in the early 1980s was an inexperienced officer named Vladimir Putin. “Totally inconspicuous,” Kalugin says of young Putin. “He was totally unremarkable and uninteresting.”

Now in his eighties, Oleg Kalugin is a US citizen and an adviser to the International Spy Museum in Washington. He was granted asylum here in 1995 and later called Putin a war criminal; a Russian court tried him in absentia for treason. I called him on a recent weekday morning and said I was working on a story about Yurchenko.

“Well, that was so many years ago,” the former KGB spy chief said in a quiet voice. After a minute or two, he warmed to the conversation, laughing occasionally. “For some reason,” he said of Yurchenko, “I didn’t like him.”

Kalugin was in St. Petersburg when he got news of Yurchenko’s August 1985 defection. It hit the KGB like a bomb. High-level KGB staff officers, the most trusted people in Soviet society, simply didn’t defect—it was a potential propaganda disaster if the news became public. “That was just unbearable,” says Kalugin. “A major trouble. Some people would really lose their careers.” Then there was the problem of the secrets themselves, the secrets Yurchenko was spilling to the enemy.

The KGB didn’t need to guess about what Yurchenko was telling the Americans. The Soviets knew something the Americans didn’t. In addition to the two traitors Yurchenko had revealed to his debriefers—Edward Lee Howard and Ronald Pelton, whose betrayals were in the past—the KGB had recruited two other moles inside US intelligence agencies, and these men were still active. One was Aldrich Ames, the CIA officer who had originally picked up Yurchenko at Andrews Air Force Base. The other mole was an FBI special agent named Robert Hanssen. Both were now providing the KGB with secret reports on the Yurchenko case. In other words, the KGB had ears inside the Virginia safe house. The safe house, unbeknownst to the Americans, was compromised.

This didn’t mean there was an obvious way for the Soviets to get Yurchenko back. There weren’t any good options. The colonel was being held under 24-7 guard, and besides, he apparently wanted to be there. Abducting him would be impossible. If he were ever to return to the Soviet fold, Yurchenko would need to meet them halfway.

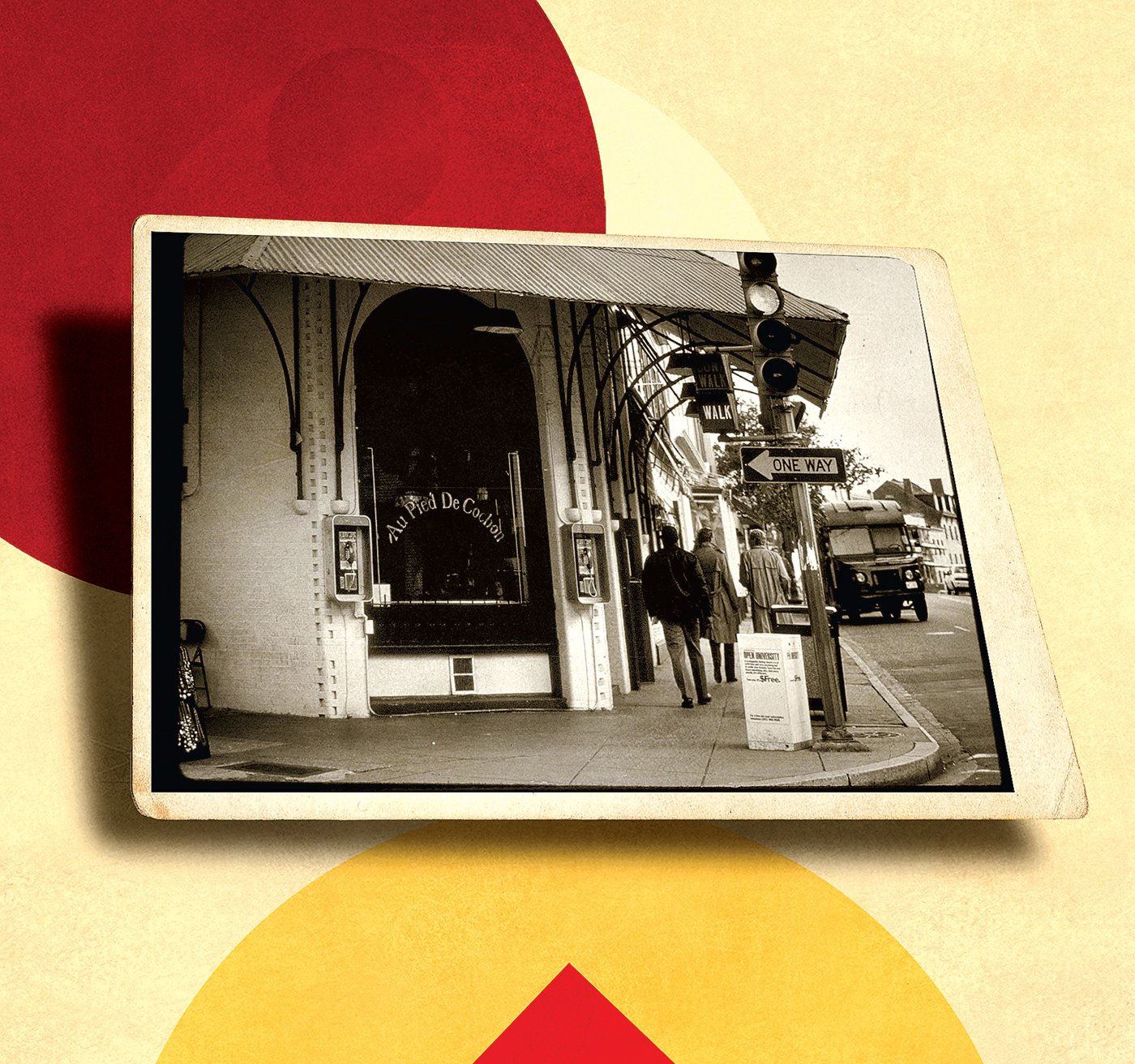

On October 31, 1985, three months after arriving in the United States, Yurchenko went to see the Halloween parade in Georgetown with his CIA psychologist, who neglected to inform his colleagues. Two days later, on November 2, Yurchenko talked his young, inexperienced CIA guard into taking him shopping at a department store in Manassas. He was carrying a few thousand dollars in cash that the CIA had given him for spending money. At the department store, he bought a new hat and a razor to shave his handlebar mustache. After making a call on a pay phone, he suggested that he and the guard go into Georgetown for food at a French restaurant called Au Pied de Cochon, on Wisconsin Avenue.

It was a cold, rainy Saturday afternoon. The guard ordered soup and lobster. Yurchenko asked him what America did to defectors who try to escape. Do they get shot? The guard said no, America didn’t treat defectors that way. Yurchenko rose. “I’m leaving now,” he said, “I’ll see you—goodbye. If I don’t come back, it’s not your fault.”

“These guys have a big plan.”

Yurchenko left the restaurant. The CIA guard did not follow.

Yurchenko walked up Wisconsin Avenue for 20 minutes to the new Soviet Embassy. The call he’d placed from the pay phone a few hours earlier had been to a contact at the embassy. Greeting him there was Victor Cherkashin, the KGB’s masterful counterintelligence chief, the man who had recruited Ames and Hanssen.

“Molodets [good man]!” Cherkashin said, as he later recounted in his book, Spy Handler. Yurchenko claimed not to know how he had ended up in the US. He said “the bastards” had kidnapped him in Rome and drugged him.

Cherkashin knew Yurchenko was lying, because his mole inside the American intelligence community had given him the Americans’ own debriefing reports. The counterintelligence chief knew Yurchenko had betrayed the USSR. But Cherkashin decided to go along with Yurchenko’s story.

“He was back now, but we didn’t know how he’d behave,” he wrote. “Maybe he’d want to return to his American friends after a couple of days. Our priority was making sure he didn’t defect again before we got him to Moscow as quickly as possible. That meant pretending to be overjoyed to see the prodigal son back on our side while posting security guards to make sure he didn’t sneak out.”

On the afternoon that Yurchenko walked out of Au Pied de Cochon, the CIA’s Colin Thompson was about to leave his house for a date when the phone rang. It was Yurchenko’s guard saying he didn’t know where the defector was. Thompson immediately called the FBI. Then Bearden and Rochford got calls, and pretty soon a bunch of guys met in Georgetown and spent the next six to eight hours prowling around outdoors in the rain, looking for their KGB friend, finally giving up around 3 am.

The next time they saw Yurchenko, he was on live television.

On November 4, Soviet diplomats called a surprise press conference at the Soviet Embassy in Washington and invited the DC press corps. Reporters arrived to find Vitaly Yurchenko in a suit and tie, sitting at a dais, flanked by several Soviet officials.

Yurchenko opened with a few words in wobbly English. “I’d like to tell you, during these three horrible months for you I didn’t have any chance to speak Russian,” he said. Then, speaking Russian through a translator, he began to tell the press what he said was the true story of his ordeal.

According to Yurchenko, on August 1 he had been sitting in St. Peter’s Square in Rome, drinking a bottle of boiled water to soothe his stomach, when “I felt something like liquid splashed on me” and “everything went dark.” When he regained consciousness, he found himself in a house in Virginia, where CIA men forced him to take “some special drugs” and interrogated him, keeping him there against his will for months. As a result of the drugs, he couldn’t recall what he had told the CIA, but he was sure he had never willingly revealed any Soviet secrets.

“Please, ask CIA officials what kind [of] secret information I gave them,” Yurchenko asked the reporters. “It would be very interesting for me to know, too, because I don’t know.” He also complained that the Americans “made me play golf” and “let me get a suntan to change the greenish color of my face.”

Although American journalists were skeptical of Yurchenko’s story—he looked healthy, tanned, not like a person who had been drugged or abused—the event “went swimmingly” from the KGB point of view, Cherkashin later wrote. “I don’t know how many Americans believed Yurchenko’s kidnap story, but his return hurt the CIA’s image regardless. The agency had either been completely taken in by a brilliant Soviet intelligence officer, or allowed one of its top Soviet defectors to slip out of its hands.”

Soon after, the KGB trundled Yurchenko into an Aeroflot plane and flew him back to Moscow, where he was welcomed as a hero. This, too, was part of the propaganda ruse: If the KGB punished Yurchenko, it would tip its hand to the Americans, revealing that it knew Yurchenko was a genuine defector, at which point the Americans might wonder how the KGB knew that and might go looking for moles again—for Ames and Hanssen, the active moles the Americans didn’t know about yet. So as hard as it was for some KGB officers to stomach, they had to give the traitor a medal instead of shooting him. “Either Yurchenko is as smart as the devil himself,” one KGB officer concluded, “or he is the luckiest bastard alive.”

US officials scrambled to explain what had just happened. Was Yurchenko a real defector who simply changed his mind? Or had he been a fraud from the start, a KGB plant who gave false information to his American handlers, leading them into a hall of mirrors?

It was a John le Carré novel come to life, the whole world chewing over the mystery. A reporter asked President Reagan at a White House press conference, “So were we had by Yurchenko?” Reagan replied, “There’s no way that you can prove that isn’t so. On the other hand, there’s no way that you can prove that it is.” The President confessed to feeling “perplexed” that anyone who could live in the United States “would prefer to live in Russia.”

An advisory panel convened by Reagan decided that the CIA and FBI had made serious mistakes. Intelligence officials were hauled in front of Congress to answer hostile questions about the episode, including the CIA’s brief attempt to find Yurchenko a prostitute. Looking back, Bearden drawls: “Maybe they think we should have gotten him someone who looked like the Rose Bowl queen. But what the f— do they know?”

The embarrassment of losing Yurchenko did light a fire under the US’s counterespionage efforts. “One of the things Yurchenko told us is that they had a program in place to recruit CIA officers, and they were willing to pay $1 million apiece for the recruitment of a CIA officer,” Rochford says. “We thought: Holy shit, that’s what we should be doing for the KGB.” Rochford started traveling around the world trying to convince KGB officers to turn. “I probably pitched anywhere between 38 and 40 KGB officers. The reason we did that is because we figured the more people we asked, the more chance you have to get it.” His effort ultimately bore fruit in 2000, when one of Rochford’s Soviet sources revealed that FBI agent Robert Hanssen was a KGB mole.

At that point, the KGB’s other mole, Aldrich Ames of the CIA, had also been caught and imprisoned. A minor conspiracy theory gained currency in US intelligence circles that appeared to make sense of the Yurchenko mess almost ten years earlier: Maybe he had been sent here by the KGB with explicit orders to reveal two of its past moles, Edward Lee Howard and Ronald Pelton, to throw America off the scent of the KGB’s active moles, Ames and Hanssen.

“Anytime you’re expending resources chasing your tail,” says Vince Houghton, the curator of the Spy Museum, “you’re less likely to expend resources to find somebody who’s already there.” But after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the breakup of the Soviet Union, former KGB officers rejected that theory in interviews, published memoirs, and personal conversations with their former American adversaries, although some US intelligence officers continued to believe that Yurchenko was a false defector from the start. The Soviet spies admitted that Yurchenko was the genuine article, an actual turncoat. “They said, look, he’s nuts. He’s a crazy guy. He was conflicted. He had a lot of personal problems. They said he’s a legitimate defector who came to you with legitimate information.”

By the time Rochford and his colleagues learned the truth about Yurchenko, the battle of wits between the American agencies and the KGB appeared to be over. When Robert Mueller took over as FBI director in 2001, he continued a downsizing of the counterintelligence department that his predecessors had started. “I was in the meeting when he told us: Stop wasting your time on something like the Russian intelligence,” recalls David Major, at the time an FBI counterintelligence leader and a former National Security Council staffer under Reagan. Major argued that it was only a matter of time before the lack of attention was “going to bite us on the ass. And it has, hasn’t it?”

Today, of course, Mueller is on the Russia beat full-time. The KGB, it appears, never really went away—it changed its name to the FSB and kept marching. When I called Yurchenko’s former CIA and FBI handlers to discuss the events of 30 years ago, each drew a line from that case to Russia’s interference in the 2016 election, as if it were all part of the same basic story. Michael Rochford said he hopes US agencies will get more aggressive about recruiting Russians to spy for America, so we can know Russia’s intentions.

“What Putin’s done in the long run is he’s woken us up,” Rochford says, “and hopefully, the leadership of the FBI and CIA are woken up, too.”

As for Vitaly Yurchenko himself, all American traces of the man have receded into time and mystery. The French restaurant where he ate his last American supper became a Five Guys. The day he escaped, he left behind his golf putter at the Virginia safe house. Rochford called it the “Yurchenko putter” and kept the club for years.

The Soviets who knew the real story of Yurchenko never forgave him for defecting. Oleg Kalugin and his KGB colleagues saw Yurchenko as “a traitor who just failed in his treason and had to come back,” he told me. “People despised him.”

I asked Kalugin if he still viewed Yurchenko as a traitor 32 years later. “Oh, yes!” he said. “Why should I have changed?” Yurchenko had betrayed his profession and punctured the myth of KGB officers as invincible chess masters, cold-eyed men who never sleep and never lose.

“Russia, the country, is run by the KGB guys,” Kalugin said. “That’s what people do not understand. Not the military—by the KGB. Either professional, like Putin, or former KGB assets. That’s what the whole country is about.”

Yurchenko may still be alive in Russia. He would be 81 now, his handlebar mustache faded to white. In the early 2000s, Milton Bearden went to Russia to research a book about the CIA’s battle against the KGB, The Main Enemy, cowritten with national-security reporter James Risen. In Moscow, Bearden sat down with several of his former KGB adversaries and interviewed them about various Cold War episodes, including Yurchenko’s defection and re-defection. The Russians were candid. Yurchenko, they said, was living in Moscow. He worked as a security officer at a Moscow bank. And one day, they said, if there was any justice, his body would be found “somewhere along the Moscow River.” Sooner or later, Vitaly Yurchenko was going to pay.

This article appears in the February 2018 issue of Washingtonian.