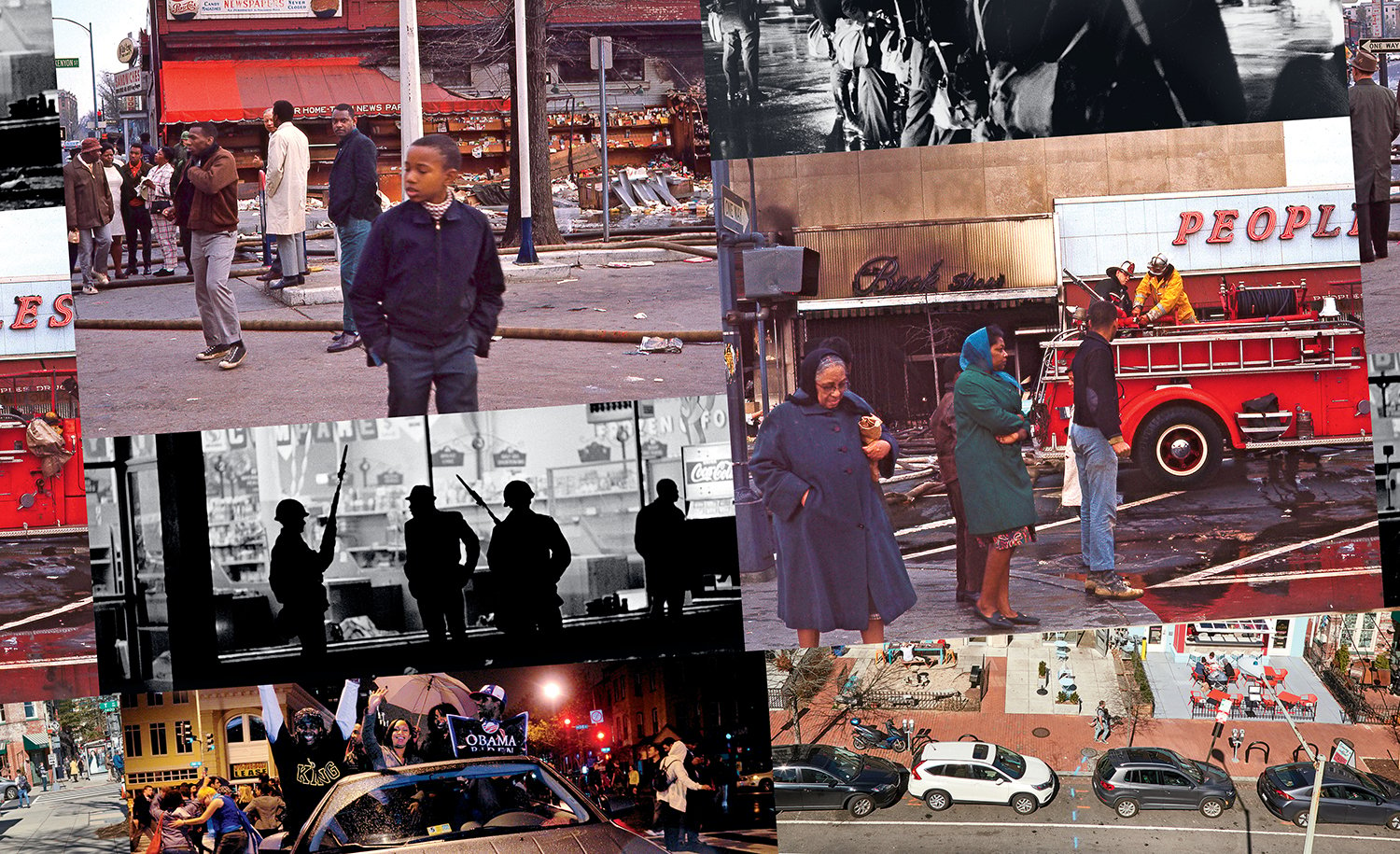

By Palm Sunday, the 14th Street corridor lay in ruin.

The corridor was the main artery of black Washington in those days. DC, as it still is, was a city marred by the lingering wounds of segregation, where the physical map of your daily life was determined by the color of your skin. The landscape west of Rock Creek Park was dominated by middle-class and wealthy whites. African-Americans kept mostly to the east, and 14th and U was a hub of shopping, culture, and entertainment where they owned and patronized hundreds of businesses.

Then King was killed and the neighborhood burned. As dawn broke on Palm Sunday, the wreckage sat desolate and smoldering. The Safeway at 14th and Chapin was reduced to a pile of twisted metal and shattered glass. Gone was the Peoples drugstore at 14th and U—and the Pleasant Hill Market a few blocks north and Smith’s Pharmacy and Ripley’s clothing store. The odor of tear gas and smoke clung to everything.

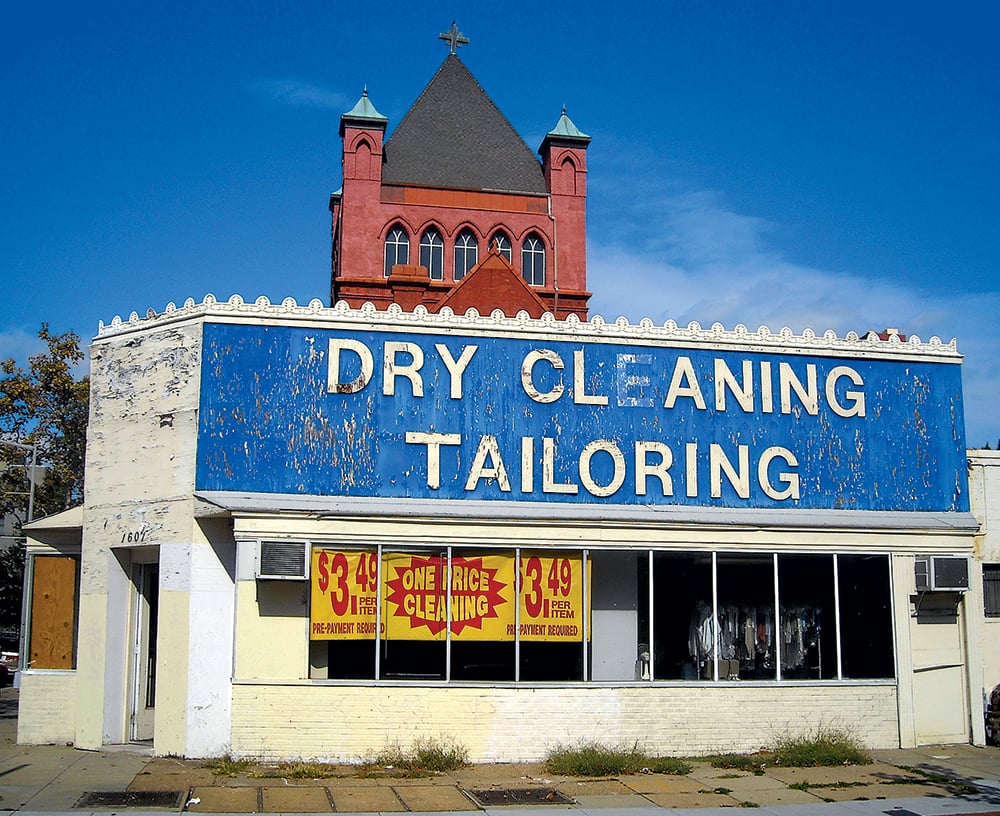

Fifty years later, it’s all hard to picture. On the corner of 14th and R, studio apartments start at $2,100 a month in a building that once was a homeless shelter; on the ground floor, a Shinola store hawks $800 watches. A block away, Teslas and Range Rovers queue at the valet stand outside the French restaurant Le Diplomate, once the crumbling shell of a dry cleaner. Up at T Street, an old auto showroom used for decades as a black Pentecostal church now houses Room & Board.

Which is to say 14th Street might bustle and thrill as it once did, but it’s a very different place with a very different population.

The story of how that happened can feel like a recent phenomenon, as if it only just began. In fact, you can go all the way back to 1968 and find the seeds of a spectacular comeback. They just weren’t always easy to recognize.

“Don’t move,” Tony Cibel heard a voice say. It was 1971, and Cibel was at Barrel House Liquors at 14th and Rhode Island, getting some change from the safe upstairs. He’d bought the store—with a giant, three-dimensional barrel protruding from its facade—the year before for next to nothing. Business was steady, but the clientele—prostitutes, pimps, bootleggers who bought booze by the case to resell after hours—meant that he had to put up with his share of drama. On this particular day, he heard the threat and looked over the balcony: A pair of robbers were holding up his two employees and a delivery guy.

Cibel hit the silent alarm, grabbed his gun, and ran downstairs. He fired at the robber fleeing out the back door, striking the man’s shoulder and taking him down. The other perpetrator escaped up Rhode Island, cash flying behind him, before the cops descended.

Cibel says he didn’t even bother installing bulletproof glass in front of the cash register after the incident: “The word went out—‘Don’t fool with that white boy. He’ll shoot you.’ That was the end of that.”

There had been talk of rebuilding 14th Street almost immediately after the riots. Within months, city leaders and the National Capital Planning Commission were working on an “urban renewal” plan for the area, and Metro’s Green Line, which hadn’t been built but was designed on paper, was rerouted through U Street and Columbia Heights to spur revitalization—a decision that would ultimately have an enormous impact.

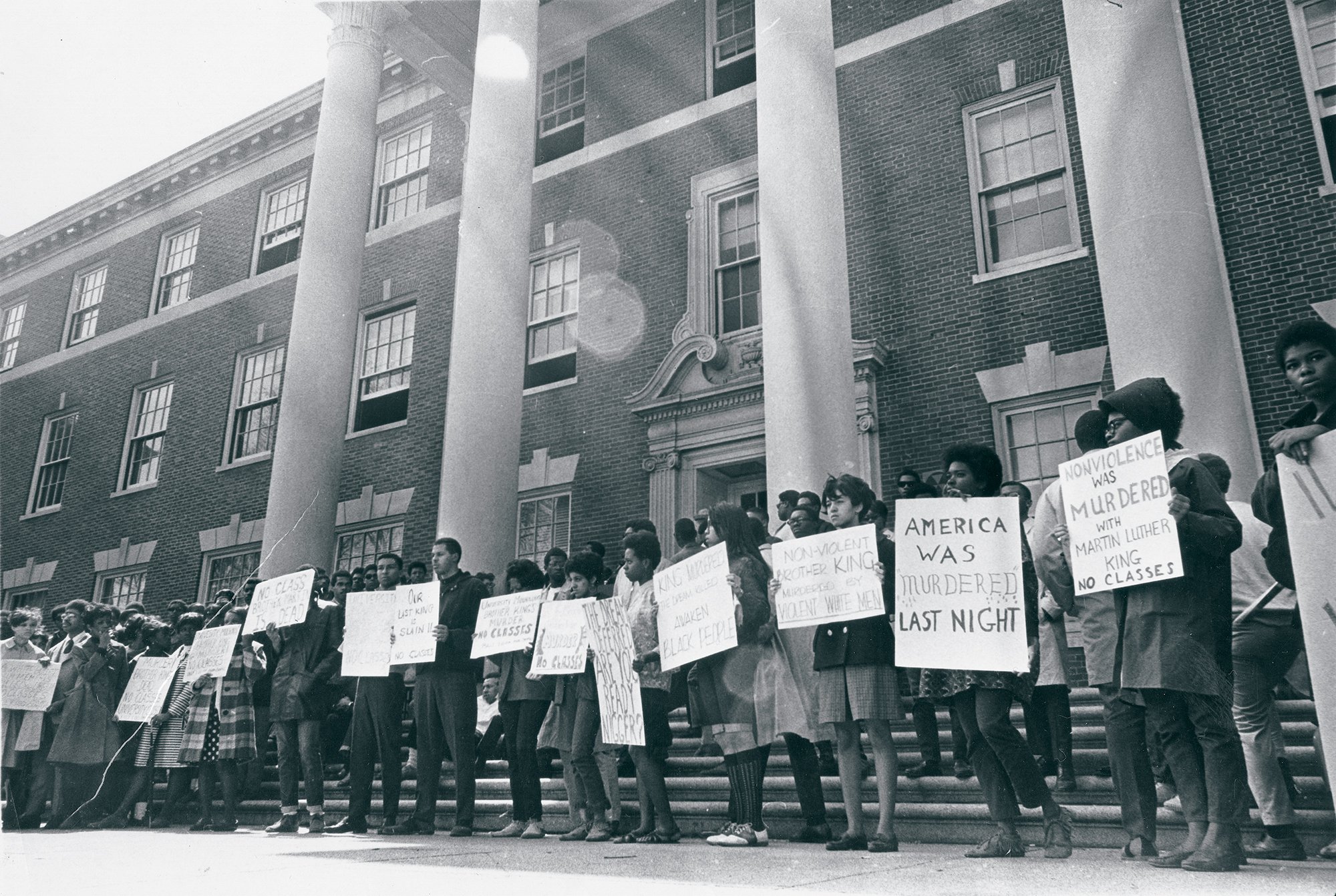

DC erupted after Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination. Protesters on the campus of Howard University on April 5, 1968. Photograph of protestors by Washington Post, Reprinted with Permission of DC Public Library/Star Collection.

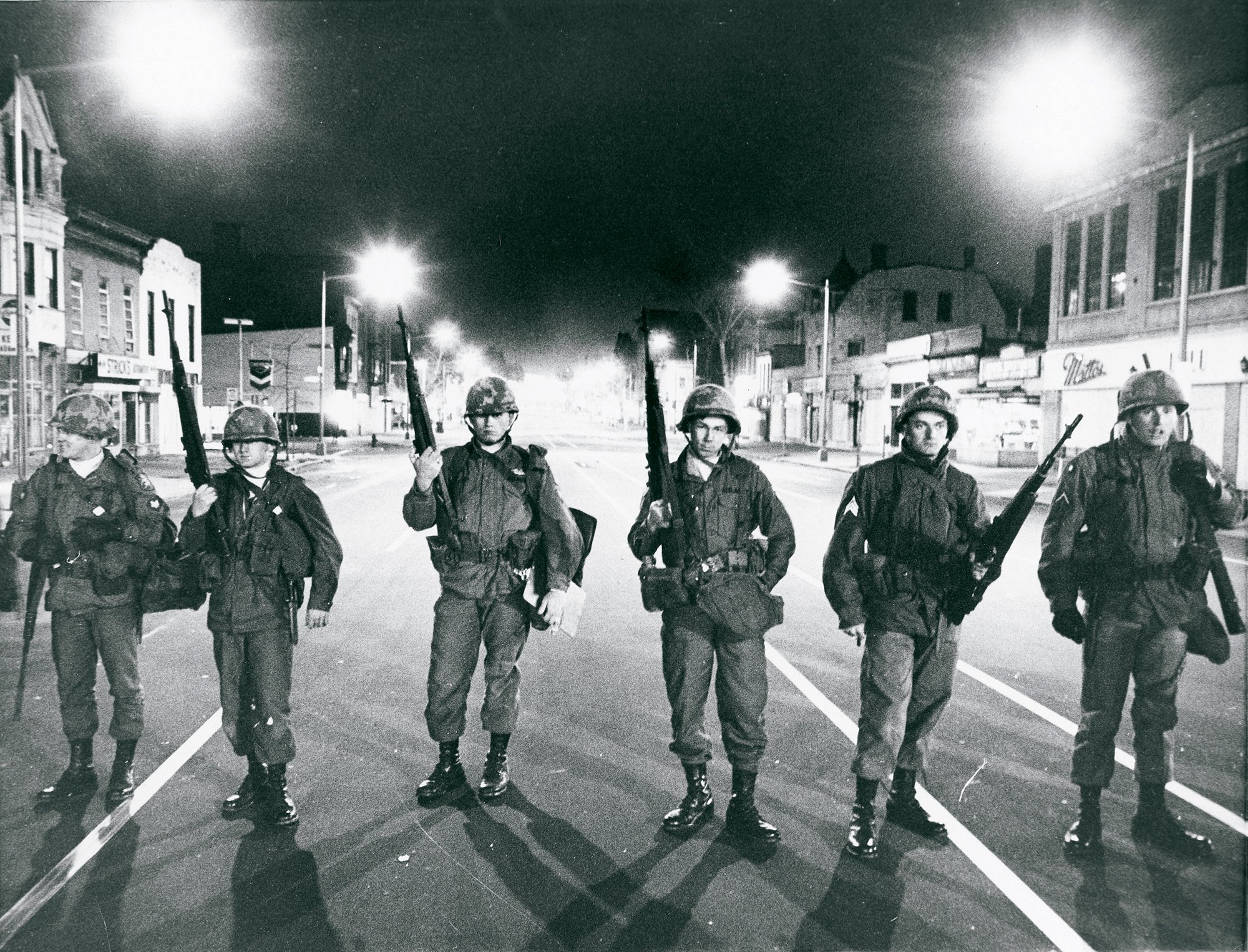

DC erupted after Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination. Protesters on the campus of Howard University on April 5, 1968. Photograph of protestors by Washington Post, Reprinted with Permission of DC Public Library/Star Collection. The city remained tense well after the initial destruction and chaos, with clashes still bubbling up. A car that was torched by a crowd at 14th and Harvard in November 1968. Photograph by Washington Post. Reprinted with Permission of DC Public Library/Star Collection.

The city remained tense well after the initial destruction and chaos, with clashes still bubbling up. A car that was torched by a crowd at 14th and Harvard in November 1968. Photograph by Washington Post. Reprinted with Permission of DC Public Library/Star Collection.  Photograph of 14th Street by UPI. Reprinted with Permission of DC Public Library.

Photograph of 14th Street by UPI. Reprinted with Permission of DC Public Library.Not that you could see it by 1971, or anytime in the next two decades. Three years after the riots, the corridor Cibel bought into hardly looked any different. DC was hurting; its population had begun declining after desegregation in the ’50s and was still falling. Business owners looking to rebuild on 14th found it nearly impossible to get insurance or loans—particularly if they were black. As a result, much of the streetscape appeared as though the riots had happened hours earlier. Instead of ribbons being cut, heroin addicts nodded off in abandoned doorways. Up the street in Columbia Heights, the city was bulldozing vacant buildings, then spray-painting the barren ground green to mimic vegetation.

Still, the cheap rent and anything-goes atmosphere were a draw for all kinds of urban pioneers who would help shape the corridor for decades to come.

Just north of U Street, activists who had moved to the neighborhood before the riots established it as a center of the Black Power movement. At the headquarters of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee—the civil-rights organization that had led freedom rides, sit-ins, and voter-registration drives in the ’60s—the focus had shifted from protesting to harnessing political influence.

Comeback or Comedown?

Fourteenth Street is such a great national model. . . . You’re looking at a sophisticated, millennial-oriented place that attracts people from throughout the region. Strolling up and down 14th Street is a unique experience. . . . Name me another place where you can see so much fashion and really hip things and great restaurants.

A group of SNCC members opened the Drum and Spear bookstore at 14th and Fairmont, a space painted bright orange whose floor-to-ceiling shelves were stocked with works by black authors and political dissidents. “Sometimes you could spot what you thought maybe was an FBI [agent] watching you, trailing you down the street,” says Charlie Cobb, one of the founders.

Nearby, Gaston Neal, a poet and Black Power leader, ran the New School for Afro-American Thought, a gathering place where courses were as varied as Swahili, politics, dance, and drumming.

Young people strode the corridor with more swagger than before. “There was tremendous energy coming out of ’68 into the ’70s about how to move the community—politically, economically, and culturally,” says Courtland Cox, another Drum and Spear founder. “Fourteenth Street was the incubator for people thinking much differently about the world.”

The phenomenon was pan-racial. A mile south, a different counterculture began to flourish. Three white female artists who had fallen for the neighborhood’s decaying but grand old rowhouses moved in. The women—sculptor and woodworker Margery Goldberg, dancer Liz Lerman, and actress Joy Zinoman—turned multiple Victorians into studios and apartments and lured other artists with the promise of plentiful space to create whatever they wanted.

Soon, half a block was lit at all hours with gallery openings and raucous parties. “In a city like Washington, where most people were a bunch of suits, this was like Brooklyn,” says Goldberg. There was even an artisanal security system. Traveling the neighborhood on foot, the artists wore bells for safety. “That way, you knew whoever was coming in the alley was a friend,” says sculptor and jewelry maker Carol Newmyer.

One day, Zinoman took a walk in search of a new space for her acting school. It was outgrowing its spot at 14th and Rhode Island, and she had designs on opening a theater, too. At the corner of 14th and Church, “we saw a warehouse door open, and we went in,” she remembers. “It was the storage place for the hot-dog carts on the Mall.”

Like many of the historic buildings along the corridor, it was sprawling, with good bones. Zinoman homed in on the sturdy columns, spaced just right for a stage. Never mind the rats scurrying underfoot—she’d found the perfect piece of real estate for Studio Theatre.

The venue opened in 1980, showcasing contemporary acts from New York and edgy plays with social-justice themes. Washington, it turned out, was starved for a new playhouse. Zinoman’s productions drew serious theater critics, whose reviews, in turn, drew audience members from all over the city and the suburbs to an area many people saw as dangerous terra incognita. “The first year, we had 18 subscribers,” she says. “The next season, there were 270.”

Still, the neighborhood didn’t get much safer, though not for lack of trying by another class of gentrifiers: the 1970s version of an HGTV obsessive. Mostly white, both gay and straight, these house hunters saw Victorian fixer-uppers in a close-to-downtown location and got to work patching plaster.

“My wife and I had just restored a little house about the size of a postage stamp on Capitol Hill, and we got these delusions of grandeur,” says Donald Smith, then an editor at the Washington Post. “We wanted a neighborhood that was kind of up-and-coming.” They bought an empty 21-room mansion directly on Logan Circle for $62,000 in 1974 and live there to this day. “Basically, we’re still working on it.”

Prostitution had become 14th Street’s best-known trade. Cars with Virginia and Maryland plates would swarm the street—johns looking for a hookup. “At the time of the World Bank’s annual meetings, you’d have the limousines up here,” remembers Frona Hall, then active in the Logan Circle Community Association. “It was sort of tourism—seedy tourism.”

It was dangerous, too. Twenty-four-year-old Pamela Mae Shipman was working the corridor in 1982 when she was forced into a red Lincoln, bludgeoned with a tire jack, and left half naked and dead in the woods off the Baltimore-Washington Parkway. Cynthia Louise Herbig, once a promising musician, was known among her fellow prostitutes as smart and cautious—the 21-year-old kept a meticulous log of her regular customers. It didn’t matter. She was stabbed to death in ’79.

Comeback or Comedown?

It’s astonishing from ten years ago, when we were pretty much the only thing on the block, to how it has developed now, with 82 restaurants and this very vibrant retail scene. . . . At the end of the day, it’s a city, so hopefully it’s going to be loud and bustling and dynamic. . . . But as we’re seeing more nightlife on the street and more trash, we want to make sure the neighborhood is kept pretty and that we’re making sure there’s somebody looking out for it.

Nearly every night, members of the Logan Circle Community Association hit the streets. Patrols of 15 to 20 neighbors would walk the length of the corridor from 10 pm to 2 am. Armed with walkie-talkies, they’d physically surround the gaggles of prostitutes and force them from their corners—a ritual that lasted years. “The pimps would throw bottles at us,” says Hall.

The neighbors tried other tactics as well. One of the more clever: a guerrilla-style bumper-sticker campaign. They printed stickers that read: “DISEASE WARNING, Occupants of this vehicle have been seen in the company of street ladies along 14th Street” and covertly slapped them onto the backs of pulled-over cars. That way, they figured, the men’s wives would be the first to spot them in the driveway the next morning.

By the end of the ’80s, Washington had earned its infamous honor as the nation’s murder capital. The crack era didn’t spare 14th Street. Its boundless supply of burned-out buildings became havens for users. Open-air drug markets operated at 14th and S and 14th and T, says Vernon Gudger, who patrolled the area as a Third District police officer. When slingers began doing deals in the booths at Ben’s Chili Bowl on U Street, owner Virginia Ali invited police to stage stings in the restaurant. She stopped selling sweets because sugar attracted addicts.

Farther north, dealers dotted corners throughout Columbia Heights. All the while, a surge of immigrants from El Salvador, escaping war in their country, gravitated to the neighborhood, with its existing Latino population and churches offering social services and sermons in Spanish. They brought with them rich traditions in food and art—adding to the multiculturalism that endures in Columbia Heights today—but also a slew of problems the city was unequipped to handle.

Many of the minors came without parents, says Lori Kaplan, president of the Latin American Youth Center, a block off 14th. She remembers kids who’d suffered violence and rape, arriving with nowhere to live. Inevitably, many got caught in the turmoil of the neighborhood.

Quique Avilés, now a writer and recovered addict, lived at 14th and Irving as a teen. He was lucky enough to have family with him and remembers the corridor as lively—“You’d always hear kids playing go-go music in the alleys”—but also harrowing. “We wouldn’t call the police. We didn’t speak English. We were coming from dictatorships where the cops were the enemy.”

Avilés wound up addicted to crack, frequenting one of the worst pockets: Clifton Terrace, the low-income-housing complex at 14th and Clifton that was a maze of drugs, gangs, and prostitution. He learned to look people in the eye when he made buys there: “If you walked in weak, they would beat you.” (The building was run by a notoriously rapacious slumlord—the kind of owner who drove down values all over the area, eventually helping lure the fixer-upper types who sent them rocketing right back up.)

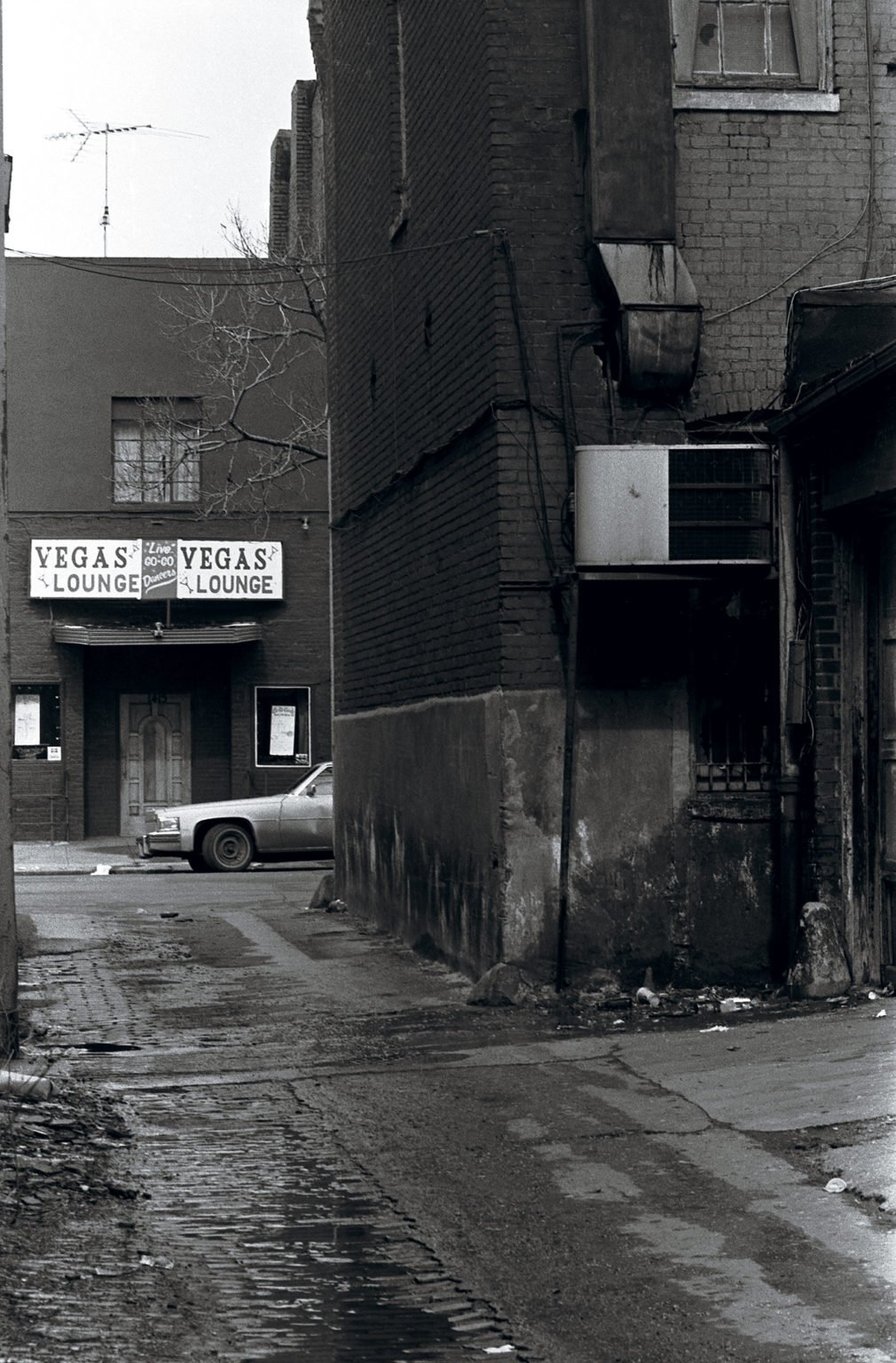

The nightlife that did manage to survive found clientele in unlikely places. Drug kingpin Rayful Edmond used to hang out at the New Vegas Lounge, at 14th and P, across from where a Whole Foods stands today. Edmond’s crew didn’t drink—and the staff said they never made trouble inside. Photograph by Michael J. Horsley.

The nightlife that did manage to survive found clientele in unlikely places. Drug kingpin Rayful Edmond used to hang out at the New Vegas Lounge, at 14th and P, across from where a Whole Foods stands today. Edmond’s crew didn’t drink—and the staff said they never made trouble inside. Photograph by Michael J. Horsley. Another business that rode out the thin years was Ben’s Chili Bowl. In the ’80s, police staged stings there—at owner Virginia Ali’s invitation. Photograph by Carol M. Highsmith.

Another business that rode out the thin years was Ben’s Chili Bowl. In the ’80s, police staged stings there—at owner Virginia Ali’s invitation. Photograph by Carol M. Highsmith.One of the main hangouts for the members of 14th Street’s underworld was the New Vegas Lounge, a jazz club turned strip joint a half block off the corridor on P Street. Prostitutes on break, some in their teens, would knock back a drink with an eye on the clock, then hustle onto the street again before they got in trouble for slacking. Rayful Edmond, king of DC’s crack trade, came in regularly with his crew.

“It was funny, they didn’t drink alcohol,” says Jessie Kittrell Jr., the owner’s son, who worked there as a bartender. “I had a drink I’d make them. It was a fruit punch—they liked the way I made it.”

As long as they didn’t cause trouble, Kittrell says, he didn’t judge the characters who came through the door, Edmond included. “Those guys were cool with me,” he recalls. “Now, once they hit the street, somebody could get killed.”

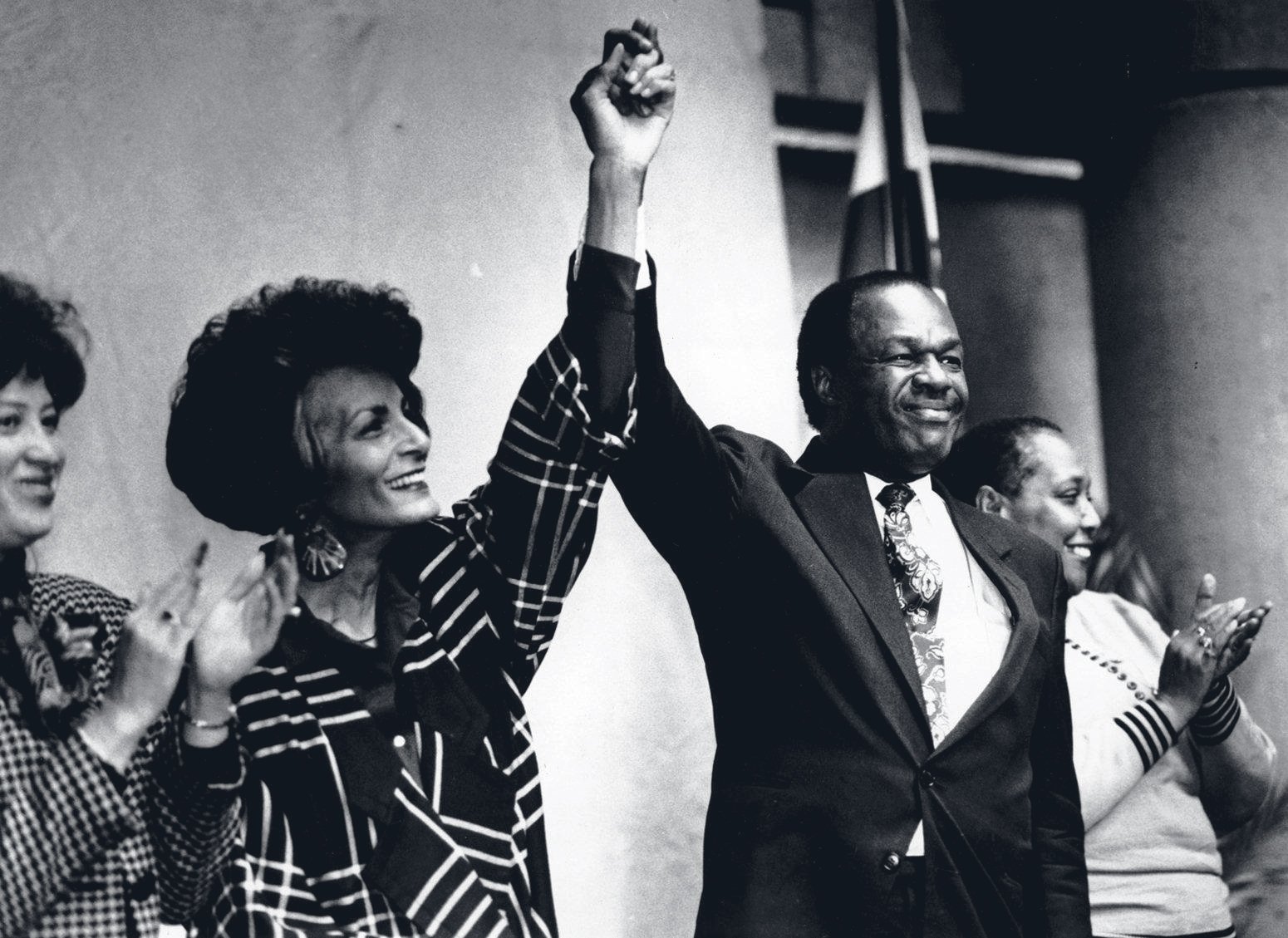

With private developers too scared to take a risk on the neighborhood, Mayor Marion Barry decided 14th Street was worthy of a bold bet by the city itself. His vision: a nearly 500,000-square-foot government office building for the flattened site at 14th and U, right where the riots had begun.

Importing city workers from perfectly suitable offices around downtown to what was considered a crack-infested wasteland was not a popular idea with the bureaucracy. Barry forged ahead. “He used to tell this story all the time. He said, ‘I had a cabinet meeting, and I tell the cabinet we’re going to take a little vote on this building,’ ” remembers Frank Smith, then the DC Council member for the area. “He’d say, ‘There were 12 people plus me. Twelve voted no, and I voted yes, so we built the building.’ ”

Eventually. Design flaws, mismanagement, and discord between the city and its contractors delayed construction for more than a year. But when the eight-story, $50-million Frank D. Reeves Municipal Center opened in September 1986, Barry wasn’t going to let those details dampen his moment.

Before a crowd of nearly 400, the mayor spoke for a half hour about the magnitude of the center’s arrival. According to the Post, he hailed it as “an anchor” of redevelopment: “Barry recalled that some people did not want the center at this site because of ‘all those drug addicts . . . all those horrible people,’ and added: ‘Look around . . . . You don’t see them here.’ ”

That wasn’t entirely true—one of the oldest drug markets in the city continued apace just a block away. And the city employees would go home at night, leaving the area as lonely as ever. Still, Barry had some reason to boast. Until then, development along the corridor had been limited almost entirely to low-income housing. It was impossible to miss the city-block-size Reeves Center, on the other hand, and it was about to import a thousand middle-class workers to the neighborhood every day—a captive audience for lunch counters, dry cleaners, and banks.

Comeback or Comedown?

There are some people who will argue, ‘Now my taxes are so high I can’t live here.’ I tell them very directly: You can’t have it both ways. Before, you were scared to leave your house at night and your property values were not great. Now your house is worth over $1 million and your streets are safe, and there are services surrounding you. But with that comes a level of participation in the form of taxes. . . . For none of that will I apologize. Every building I’ve bought was vacant, so I’m not lining my pockets at the expense of others.

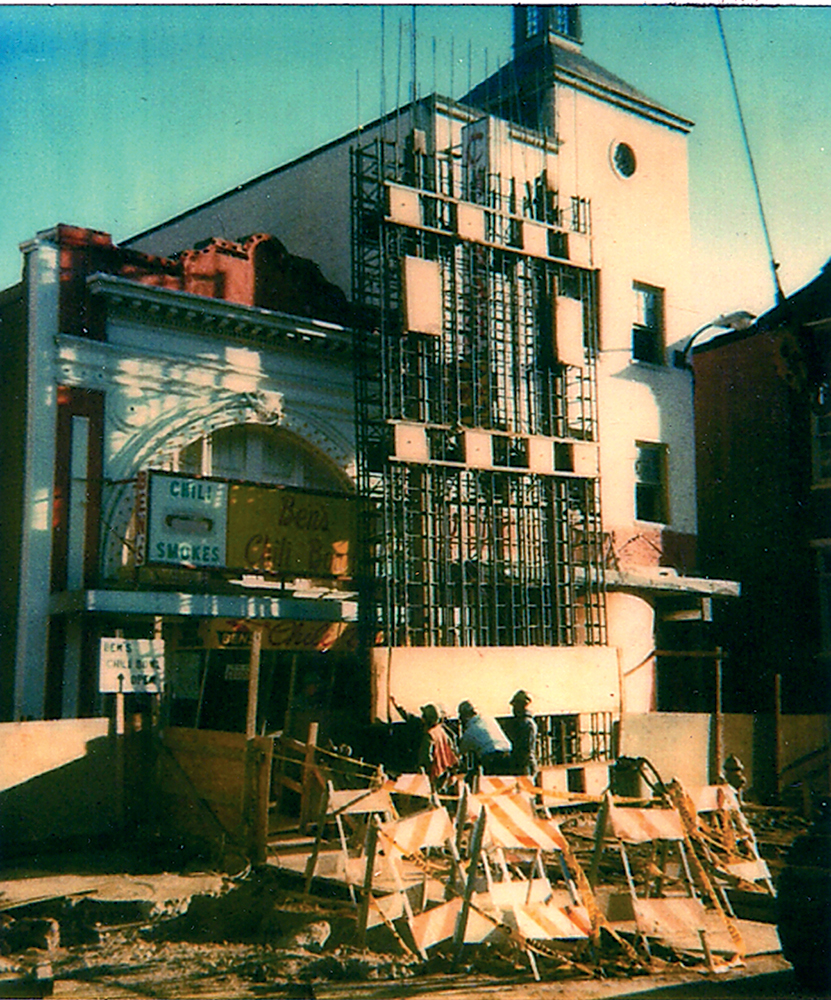

At least that was the theory. In reality, prospective business owners remained skittish, while those with “we’re open” signs were finding it increasingly hard to actually stay open—for reasons that had nothing to do with, in Barry’s words, “all those horrible people.” It was Metro, that force for redevelopment, that was making their lives miserable.

Almost two decades after the riots and the decision to help the neighborhood by rerouting the trains, construction was finally under way. It turned much of U Street into an impassable trench. The logistics were so bad, says Virginia Ali, that her late husband, Ben, considered closing the Chili Bowl—a prospect he hadn’t entertained even after the devastation of ’68. Some mornings, they’d show up to work to find the floor submerged in muddy water. Other days, they’d have to evacuate when crews hit a gas line. Hard as it is to believe, she says, “it was more difficult than surviving the riots.”

Fourteenth Street, though, remained intact, and to Jim Graham it looked like a natural fit. Graham had recently become president of Whitman-Walker Clinic, a nonprofit health center for the gay and lesbian community. In the ’80s, the organization was fixated almost entirely on a terrifying new illness ravaging Washington’s gay community: AIDS. While Whitman-Walker offered all kinds of services to help, its operations were in different buildings around Northwest. Graham wanted to centralize things.

Other social-service nonprofits were moving onto the corridor, encouraged by Barry’s vision, and Graham himself admired Barry for being one of the first big-city mayors to acknowledge the AIDS crisis. But more important, the neighborhood was now full of gay residents who’d moved in to fix up houses. A clinic there made sense.

“A lot of us who were gay men at the time were just living our lives expecting that we would end up getting a diagnosis ourselves,” recalls Dan Bruner, Whitman-Walker’s senior policy director, who started as a volunteer there in the ’80s. Graham found a building at 14th and S that was large enough to provide medical, counseling, nutrition, and legal services under one roof, and the group moved in in 1987.

For dying men who’d been used to trudging around the city in search of various components of their care, the benefits were immediate. “They were living in a world where they were physical pariahs,” Bruner says—here was the rare place that an AIDS patient could find comfort and companionship. But Whitman-Walker also became known as more than a clinic. A buddy program paired healthy people with sick men, to help with errands or just to offer company. The organization also operated a food bank, because adequate nutrition was essential to keeping up its patients’ strength.

Metro, which ultimately cemented the area’s new vibrancy, initially did the opposite. Construction turned U Street into an impassable trench—and almost did what the riots couldn’t: cause Ben’s to close. Photograph courtesy of Ben’s Chili Bowl.

Metro, which ultimately cemented the area’s new vibrancy, initially did the opposite. Construction turned U Street into an impassable trench—and almost did what the riots couldn’t: cause Ben’s to close. Photograph courtesy of Ben’s Chili Bowl. Whitman-Walker clinic’s arrival helped establish the corridor as a center of gay Washington. Photograph courtesy of Whitman-Walker Health.

Whitman-Walker clinic’s arrival helped establish the corridor as a center of gay Washington. Photograph courtesy of Whitman-Walker Health. Fourteenth and Q: site of the future Le Diplomate brasserie. Photograph courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Fourteenth and Q: site of the future Le Diplomate brasserie. Photograph courtesy Wikimedia Commons. The programs brought healthy men like Bruner to the neighborhood, too, as volunteers. “Whitman-Walker became the de facto community center for a number of years,” he says, and cemented 14th Street as essential to gay Washington.

By the ’90s, the District was a recurring one-liner on late-night TV. First, the FBI caught Marion Barry on tape smoking crack. Next, the city nearly went bankrupt. In 1995, with Barry back at the helm of government, DC looked so ill-equipped to handle the crisis that Congress placed the city under the power of a federal control board.

And yet—it was during this same period that the fortunes of 14th Street began to turn.

A punk-rock musician named Dante Ferrando was one of the first investors. For years, the District’s underground music scene had mostly revolved around the 9:30 Club—then located downtown—and a venue called DC Space. When the latter announced it was shuttering, Ferrando saw his opening for a club on 14th. He gathered other backers (including Foo Fighters frontman Dave Grohl), renovated a former auto-repair shop near T, and opened the Black Cat, booking major punk bands such as Fugazi and Rancid. Suddenly, white kids from upper Northwest had a reason to hang out on 14th.

Gay-nightlife promoter Mark Lee started the Lizard Lounge—a weekly Sunday-night dance party at 14th and Church. The gay party scene was mostly limited to the bars along 17th Street, so Lee printed fliers with the tag line “Only three short residential blocks from 17th.” The subtext, he jokes: “Okay, girls, you can make it! Keep your head down and run!” On a typical Sunday, he’d pack in 600 to 700 people.

The northwest corner of 14th and Rhode Island was a 7-Eleven in 1999 . . .

The northwest corner of 14th and Rhode Island was a 7-Eleven in 1999 . . . . . . a Caribou Coffee in 2002 . . .

. . . a Caribou Coffee in 2002 . . . ... a construction site in 2001 ...

... a construction site in 2001 ... . . . and condos with a Shake Shack in 2017. Photographs courtesy of Abdo Development.

. . . and condos with a Shake Shack in 2017. Photographs courtesy of Abdo Development. Farther down 14th toward Logan Circle, two young developers named Monty Hoffman and Jim Abdo were prospecting for old rowhouses to flip into luxury condos. The men would eventually count themselves among the most prolific developers in DC. (Hoffman built the Wharf.) But back then, lenders thought they were crazy—they each had to take out equity lines on other properties to finance their first projects east of 16th Street.

As a residential proposition, the area around 14th still wasn’t a sure bet for people who had other choices. But the artists and musicians who’d already arrived lent it a cool factor. On U Street, Metro was finally running, and a smattering of small restaurants and bars had moved in. Abdo and Hoffman were hopeful that buyers would show up.

Comeback or Comedown?

I’m just impressed with what I see. On a weekend night—Friday and Saturday night after midnight—when you go out there, it’s like you’re on Broadway. There’s so many young people up and down the street and so many things to do. They’re going to a music hall or the club or the theater or just to have something to eat. I think it’s amazing.

In 1996, Hoffman targeted a palatial Victorian mansion on Logan Circle, built in 1877 by President Ulysses Grant’s son. Inside, he encountered a divorcing couple at war—one of them lived in a corner of the lowest level, the other in a corner of the top floor, where the leaking roof had created a pond. Hoffman gave them $250,000 for the place, turned it into eight condos, and sold out the whole building for more than $2 million. Next, he built 14 additional condos on another section of the circle.

In 1998, Abdo bought a vacant rowhouse at 15th and P, converting it into four light-filled units that sold out in days for about $450,000 apiece. Then he snapped up the lot next door and continued his buying spree eastward along P Street and Rhode Island. It was the beginning of a land rush—one that would beautify the streetscape and bolster the tax base but have a decidedly mixed impact on many people who had called the neighborhood home.

Another developer, Chris Donatelli, was focused on building a grocery store for the growing number of households. He had bought a city-block-size property at 13th and V, site of the long-closed Children’s Hospital, and needed a tenant. So one of his partners dialed up the regional president of a high-end grocery chain called Fresh Fields—now known as Whole Foods.

“They came down. They looked at the site. The president really liked the area. He said it was analogous to some of the other urban stores they’d done,” Donatelli remembers. “He was actually very bullish.”

Donatelli began to draw up a lease. Then word got out.

When homeowners in the 1400 block of Q Street heard a rumor that Fresh Fields was headed to 13th and V, they scoffed.

“We all said, ‘Well that’s ridiculous. There are drug dealers there. You couldn’t go in there to buy your lovely Brie,’ ” says Carol Felix. She and her husband, Wayne Dickson, both in commercial real estate, believed their neighborhood had a much better property for the store—a rundown parking garage on P Street between 14th and 15th. They convened a planning session in their kitchen to plot with neighbors about how to win the store.

As it happened, their block was home to a virtual dream team for such an endeavor. A pair of London School of Economics alums compiled contrasting demographic profiles of the rival locations, showing that neighbors around P Street were wealthier and better educated than those up by V. The resident PR exec crafted a messaging strategy. A director/producer arranged a video shoot of the old Children’s Hospital site, in which she captured what appeared to be an actual drug sale in progress. Together, the group staged photo sessions in front of the parking garage, holding big signs that read: future home of fresh fields and please in my backyard.

They bundled the materials into a tidy package for the company’s Mid-Atlantic president, Chris Hitt, and dropped it off at Fresh Fields’ regional headquarters in Rockville. And that was only half of their upstart lobbying campaign. The neighbors printed thousands of hot-pink postcards urging Hitt to open the store on P Street, passed them out at Metro stops, and encouraged passersby to sign them and mail them to Fresh Fields.

Jim Abdo, meanwhile, called in a favor to one of his luxury-condo buyers. He was invested in property surrounding the garage and wanted to introduce the retailer to its potential customer base. He arranged to meet Chris Hitt in the buyer’s unit.

Comeback or Comedown?

Everybody wants their neighborhood to get better, but not so much better that you can’t live there anymore. There’s a difference between a nice, independently owned shop opening and [developers] with designs on changing the area for long-term, large-scale gain. They don’t have a face. There’s no one to talk to. There’s no one to yell at. They’re just a machine. . . . If I was able to pick this neighborhood at any point in time, it would not be this one. It feels a little sterile.

“This was like catching the great white whale,” Abdo says. “I walked him in, said, ‘This is what I’m building, this is what these people are paying, this is how they’re designing and furnishing their homes. You can look out this window and you can see the parking garage from it, and that’s where you need to put the store.’ ”

Hitt, now retired from Whole Foods, re-members the crusade: “It all got us moving towards completing the deal. In some ways, I was even more interested in [the Children’s Hospital] location. That project could have theoretically been built for less money. But in the end—because we’ve got all these models we use in determining the possibilities of each location—the model wasn’t as strong as P Street.” The store opened in 2000. “It was a huge success from day one,” Hitt says.

Donatelli still believes that his site at 13th and V would have been better. But he doesn’t sound too broken up. He partnered with another company to build 98 townhouses on the land, and they quickly sold out.

DC motored into the new millennium with unprecedented momentum. The control board was history; the new mayor, Anthony Williams, had run on the promise that he could repair the District’s sullied image. He bulked up the planning office, which had atrophied over the previous 20 years, and launched a major push to develop DC’s waterfronts, downtown, and neglected neighborhoods. To be successful, he’d have to do what might have seemed impossible before the Whole Foods coup: convince other major national retailers that they should have a footprint in the city.

From another mayor, Williams had heard about Las Vegas’s International Conference of Shopping Centers: Every spring, public officials flocked to the convention center in Sin City to schmooze with thousands of commercial real-estate brokers seeking new locations for their retail clients. DC had never attended. “We were just considered a joke,” he says.

Though they weren’t allowed to have a booth, Williams and his team did everything they could to get in front of the brokers anyway. “There was a hotel adjacent to the convention center,” says Eric Price, then deputy mayor of planning and economic development. “We would wait by the elevators to catch them as they came out, to walk them over to the convention center, and to sell them on the District.”

The DC officials brought with them reams of data: Residents ventured outside city limits to shop in places like Montgomery County, they explained, but if retailers opened in DC, they could capture that spending power.

At the same time, the mayor’s planning director, Andy Altman, was mapping out an audacious plan to expand the city’s population. A pair of economists at the Brookings Institution, Carol O’Cleireacain and Alice Rivlin, had published a report proposing that the District aim to grow by 100,000 new residents. “The city was in really bad shape. The way to get back to prosperity seemed to be to grow the tax base,” explains Rivlin.

The Williams administration adopted the paper as official policy. “We took that vision and said, ‘Well, how would that lay out?’ ” says Altman. “ ‘How would you begin to achieve that aspiration?’ ”

One way was by supporting private developers who wanted to build new housing—including around 14th and P, where Whole Foods had ignited a gold rush. The city communicated more openly with builders and improved coordination among the various agencies whose sign-offs they needed to finish their projects. But city hall could have the biggest impact in places where it controlled the land. All over town, District-owned parcels sat fallow, adding nothing to the tax rolls. Along 14th Street, it was Columbia Heights, where 13 public acres around the neighborhood’s new Metro station had languished since 1968, that was the worst offender. “It looked like Dunkirk after World War II,” says Williams.

Comeback or Comedown?

Fourteenth Street is successful in providing the kind of retailers, restaurants, and theaters that people who have come to the District want. It’s a success in terms of the underlying support to the District in taxes and other fees. . . . But gentrification always has a plus and a minus in urban communities. It requires a great deal of thinking on the part of public officials about how to make sure the vibrancy that results does not also create such a wedge in terms of race and class that the city becomes monolithic.

Neighbors were bitterly divided over the best way to proceed. One camp favored a single plan to turn all 13 acres into shops, housing, a movie theater, and offices and restore the historic Tivoli Theatre. Another—which included longtime African-American community leader Robert Moore—backed a pair of pitches that would build a retail complex called DC USA, a Giant grocery store, and townhouses and divide the Tivoli into shops. Moore’s support bolstered the second proposal, particularly with older residents. After a lot of impassioned meetings and at least one threatened lawsuit, the city ultimately sided with him.

Williams’s team then turned to the next fight: convincing Target to come to the new shopping center. At the time, the chain was a suburban staple—and unknown in the city. Price, the deputy mayor, knew Target’s real-estate brokers from the Las Vegas conferences and began lobbying them. “Anytime there was a retail conference we could go to, anywhere we could bump into them, we would be there,” he says.

In the meantime, the city bid out some of the remaining sites around the Metro for housing, requiring that 20 percent of it be affordable. Chris Donatelli, the developer who’d lost Whole Foods, won them, erecting hundreds of apartments and condos. By 2008, Target was open, along with Best Buy and Bed, Bath and Beyond—a retail mix that would serve working-class and wealthier residents alike and that branded the city neighborhood as a safe space for mainstream, middle-American shopping.

That Columbia Heights ended up with such economical retail is traceable to the city’s active role in its development—a direct contrast to what had been going on down the street.

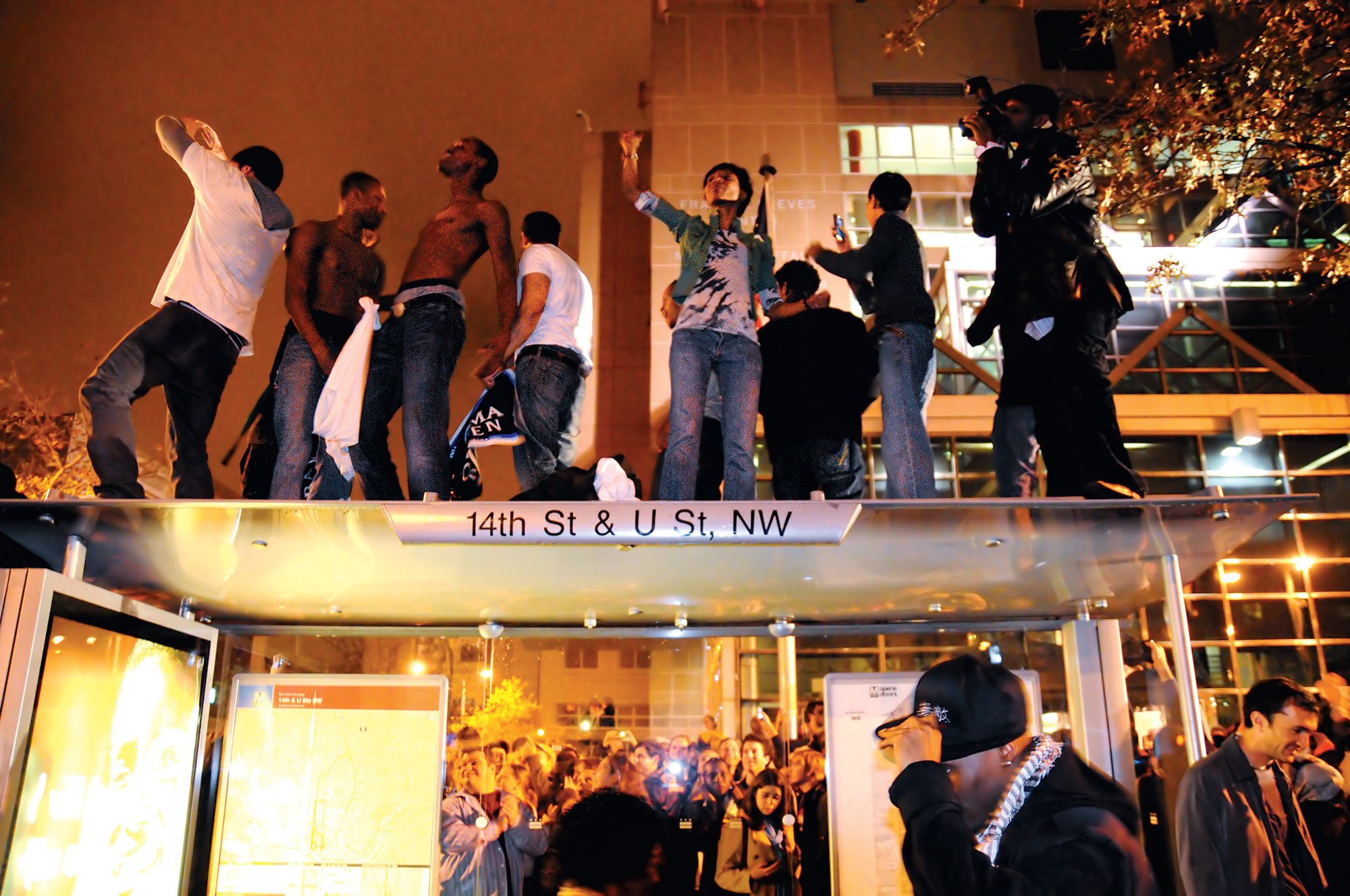

For the first time since 1968, the intersection of 14th and U was again flooded with thousands of screaming, crying young people. This crowd, though, was overcome with joy. It was Election Night 2008. Barack Obama was going to become the nation’s first African-American President.

By then, the 14th Street corridor looked nothing like it had the last time it was spontaneously mobbed. There were luxury lofts in old auto showrooms built by developers who’d rushed in after Whole Foods, as well as glassy apartments above coffee shops. There was a wine bar (Cork) and a gastropub serving pâté and sweetbreads (Bar Pilar). Nightlife tycoons and brothers Eric and Ian Hilton had opened Marvin, a lounge named for singer Marvin Gaye, in a space that used to house a Subway franchise.

The area was well on its way to becoming the it neighborhood, a phenomenon hastened by the arrival of the Obama administration and its millennial staffers. (As the New York Times reported in 2010, the President’s twentysomething employees referred to U Street, Columbia Heights, and Logan Circle as “campus.”) One new restaurant (Estadio) begat demand for another (Pearl Dive Oyster Palace) and another (Ghibellina, Ted’s Bulletin, Kapnos). Suddenly you couldn’t score a cocktail on 14th Street for less than $12.

The city’s plan to lure 100,000 new residents no longer seemed outlandish. From 2000 to 2010, the DC population grew from 572,000 to 602,000. Nearly 10,000 of those newcomers settled in the area that includes 14th Street. (The city finally hit the 100,000 milestone in 2015.) But as a result, real estate in the neighborhood is no longer plentiful or affordable. A rowhouse in Logan Circle can set you back as much as $2 million or $3 million; in Columbia Heights, you can pay upward of a million.

Comeback or Comedown?

I don’t think 14th Street can sustain itself in the long run, because the housing costs are so high and there’s not enough elasticity in the wages. People are tripling up in these apartments, living like they’re college students, and that’s acceptable only for a short period of time. The irony is the real-estate people tell you that people like the neighborhood because it’s a little bit funky, it has a history of music and culture, but that’s disappearing. You gotta keep the culture here—otherwise it doesn’t have a chance.

What’s more, retail rents along 14th, now home to upscale design stores and a Trader Joe’s, are too expensive to attract funky, local haunts—such as Home Rule, a pioneer that opened in 1999, or the vintage furnishings store Miss Pixie’s, which moved to 14th from Adams Morgan in 2005. The boom that was so many years in the making now has some people ruing how establishment the corridor has become.

“They just opened a La-Z-Boy store. They’re opening a Smoothie King across from Estadio,” laments restaurateur Jeff Black, owner of Pearl Dive Oyster Palace. “These are not things that add coolness and hipness to a neighborhood. These are things that hurt.”

Totems of the corridor’s less prosperous past are harder to find these days, but they remain. The New Vegas Lounge, once again a jazz club, refused to sell to the developers who turned P Street into a wall of apartments and condos—a squat, blue-painted holdout sitting defiantly across from Whole Foods. Barrel House Liquors is still there, too, though it’s a door down from its original spot—the old storefront with the giant barrel is becoming apartments.

While rising rents drove out other actors and artists, Studio Theatre expanded into three adjacent buildings at 14th and P, which Joy Zinoman, now retired, and her board raised enough money to buy. “I believed the only way that artists could possibly do anything was to have a stake in the real estate,” she says. Today, Studio is among the District’s most successful theaters.

Whitman-Walker Health, as it’s now known, might not have been able to afford to stay on 14th Street, either, without taking a direct stake in the land, something it was able to do thanks to many of its earliest clients. More than a dozen patients who died during the AIDS crisis in the ’80s bequeathed their estates to the organization.

The clinic now serves a wider population out of a glassy, modern building south of Q Street. It’s also erecting another building a few blocks up at 14th and R. One day last fall, developers, neighborhood activists, and city officials gathered for the groundbreaking. DC Council member Jack Evans took the podium on a perfect Washington afternoon—70 degrees, sunny, breezy.

“14th Street wasn’t always like how it is today,” he said. “It was known for two things: drugs and . . . .” The audience dutifully completed the sentence for him: “Prostitution.”

Few would deny the corridor that leap of progress. Yet you don’t have to look very hard to see that there’s one thing 50 years of slow growth hasn’t changed on 14th Street: It’s still riven by race.

“[Anthony Williams] pushed for the white people to come,” says David Brown, who grew up in a rowhouse on Corcoran Street near Logan Circle. “I’m still not used to the new 14th Street.”

Brown works at Crown Pawnbrokers, just south of S—one of the rare 14th Street businesses in existence since before the riots. But he doesn’t live in the neighborhood anymore. In 1971, he says, his landlords put his house on the market for $17,000. When he tried to buy it, “they wanted a $10,000 down payment”—nearly 60 percent of the list price—a tactic he believes was meant to push out his African-American family. He bought a house for $34,000 at 11th and Girard instead, with only 10 percent down. “It hurts me when I talk about that part of it,” Brown says. “A lot of black people who left then can’t get back in.”

Tony Gittens, who was features editor of the Howard University newspaper during the riots, says the memories of those days on 14th Street are still with him. Now director of Filmfest DC, he remembers the first time he saw a white woman jogging in the neighborhood after dark. It was 2007, and he was working for the DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities in an office at 14th and Harvard.

“I’m saying, ‘What is she doing?’ And then I realized the whole riot thing was not part of her experience. It’s in my DNA. It’s not in theirs.”

This article appeared in the April 2018 issue of Washingtonian.