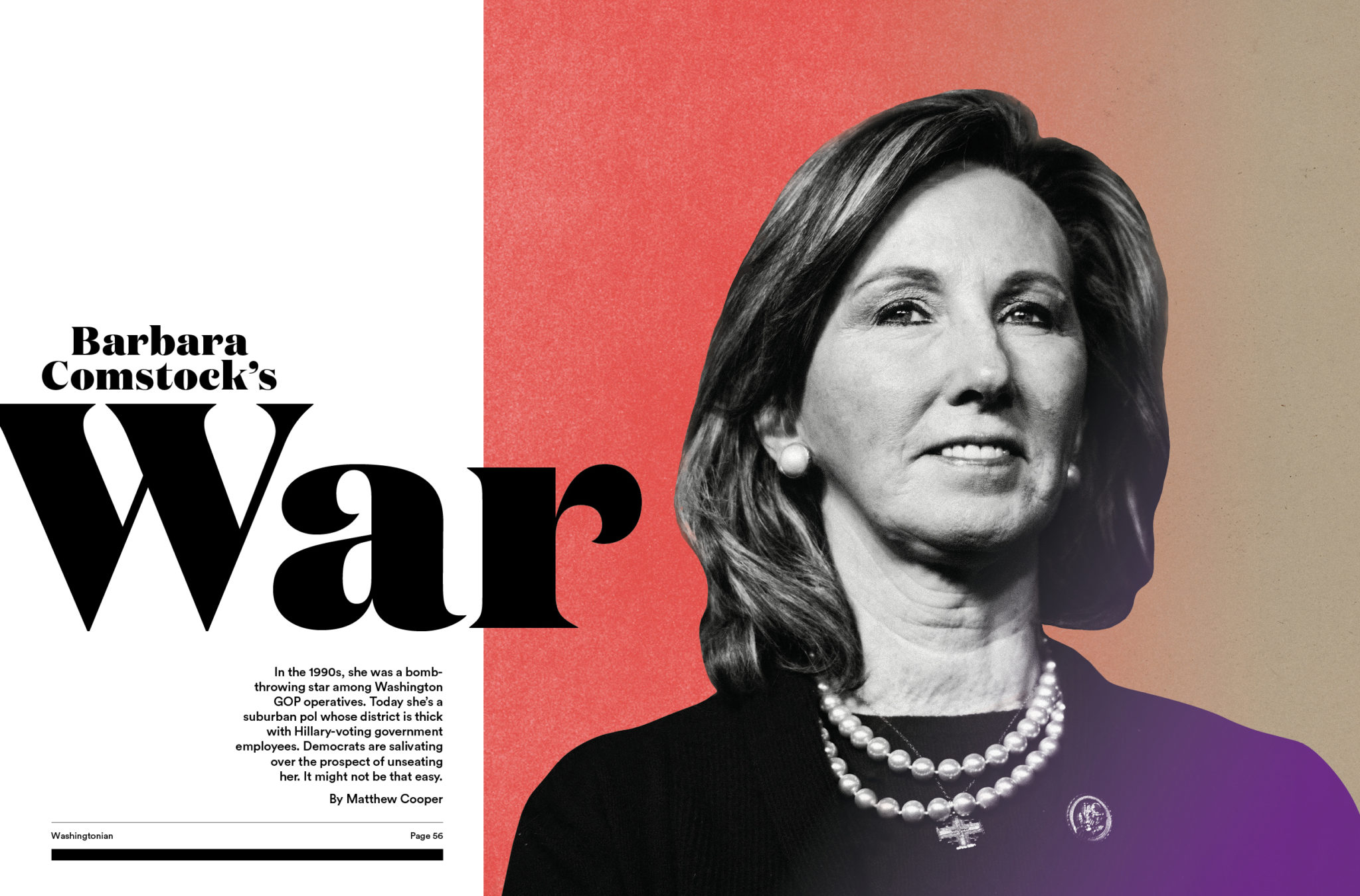

It was February 6—a cloudy winter day in Washington—and more than a dozen members of Congress had gathered at the White House. Ostensibly, they were in the Cabinet Room with the President to discuss gang violence, but the prospect of another government shutdown was on everyone’s mind. A stopgap funding measure was about to run out, and Donald Trump, full of vinegar, had said he’d once again “love to see a shutdown” over any number of party confrontations.

One of the attendees at the meeting was Barbara Comstock, the second-term congresswoman from McLean. Seated at the northern end of the cabinet table, the Republican legislator pushed back, gently but firmly, at the President’s suggestion that the anti-gang legislation sponsored by Comstock should force the government to go dark. “We don’t need a government shutdown on this,” she said. “I think both sides have learned that a government shutdown was bad, it wasn’t good for them. And we do have bipartisan support on these things.”

“You can say what you want,” interjected Trump, looking at her. “We’re not getting support from the Democrats on this legislation.”

Comstock, who even critics will admit is tenacious, continued to make her case despite the scowl crossing the President’s face. Eventually, he cut her off: “Thanks, Barbara.”

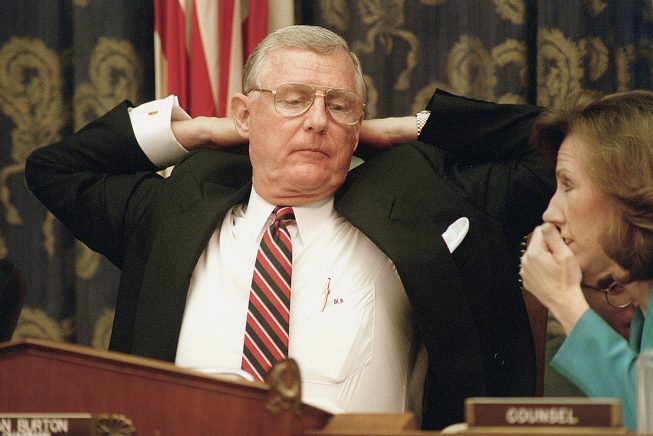

Comstock emerged during the 1990s partisan wars. Here, at a forum on the Bill Clinton investigation. Photograph courtesy of C-SPAN.

Comstock emerged during the 1990s partisan wars. Here, at a forum on the Bill Clinton investigation. Photograph courtesy of C-SPAN. Comstock with Representative Dan Burton, who publicized conspiracy theories claiming that a Clinton aide was murdered. Photograph courtesy of C-SPAN.

Comstock with Representative Dan Burton, who publicized conspiracy theories claiming that a Clinton aide was murdered. Photograph courtesy of C-SPAN.In a sense, Trump and Comstock have traded places politically—a reversal that shows just how topsy-turvy our era has become. Two decades ago, Trump was a species of political moderate, someone with a soft spot for gun control and kind words for Bill and Hillary Clinton. Comstock, on the other hand, was a minor Beltway celebrity in her thirties, a conservative operative well versed in the dark arts of opposition at a time when right-wing ultras peddled theories accusing the Clintons of murder. Trump scoffed at Comstockian crusades such as impeachment. (“They’ve taken nothing and made it a big monster,” he said in reference to the Monica Lewinsky scandal.) Comstock, meanwhile, waded deep into the conspiratorial details of Whitewater.

Nowadays, it’s the President who drips with unfounded conspiracy theories and Comstock who plays the can’t-we-all-get-along bridge-builder who explicitly said she wouldn’t vote for him in 2016. Comstock’s journey from Javert to gentility is in part the natural progression from staffer to legislator who can speak for herself instead of her boss. It also represents her need to reflect a moderate district instead of the GOP house: The well-tended lawns of Leesburg aren’t great soil for the fiery crusades of the younger Comstock, but they’re fecund terrain for a 59-year-old grandmother preaching bipartisanship. To be sure, some of her transformation has the whiff of opportunism. Was her rare vote last year to keep Obamacare alive a real conversion or an expedient move in a district that Hillary won by 10 percent?

Either way, it explains why Comstock’s reelection run may well be the hardest-fought in the history of her Northern Virginia constituency—and watched closely among the group of national political strategists who used to be the congresswoman’s colleagues. If any politician can offer a lesson about Republican survival in the age of Trump, it’s Barbara Jean Comstock, who has to navigate between swing voters, a combustible President, and her own past.

One of the first songs by the Bee Gees was a little-remembered tune called “Barbara Came to Stay.” It seems appropriate for Comstock and Washington. Her arc is familiar: College kid moves inside the Beltway, becomes staffer, then lawyer-lobbyist, and later moves into politics.

Born to middle-class parents—her dad worked for Shell—Comstock was an intern for the senior senator from her native Massachusetts, Ted Kennedy, while she was attending Middlebury College in Vermont. After graduating, she came to DC full-time. She married her husband, Chip, a well-liked teacher and administrator in the Fairfax and Montgomery County school systems, while she was still at Georgetown Law. The two live in a five-bedroom house in McLean valued around $1.5 million. They have three children.

By the time she was in Washington, Comstock was a conservative. For her first job on Capitol Hill, she couldn’t have chosen a better mentor: Representative Frank Wolf, who held the 10th in Republican hands for 34 years before retiring. The district was more Republican then, but it still demanded that its representative be willing to work across the aisle and to break from GOP orthodoxy on things such as funding for public transportation. It was as a staffer that Comstock displayed traits that have since helped her as a politician: an insanely strong work ethic and an ability to make connections and friendships, necessary for any pol. (She has lots of Democratic friends, including Donna Brazile, the campaign strategist.)

She also displayed qualities—most notably a fierce partisanship—that wouldn’t have played in, say, McLean, but that helped make her a big deal as a staffer. She became chief counsel on the House Government Reform Committee just as Republicans were beginning their crusades against Whitewater and its spawn—Filegate, Travelgate, and other Clinton scandals. Her later business partner, Mark Corallo, who worked for the House leadership at the time, recalls “that she was never going to let the boys outwork her.” She cut a vibrant figure. They were “these four blond lawyers”—the others were Barbara Olson, the conservative lawyer who was killed on 9/11; Laura Ingraham, who’d go on to become a famous Fox News host; and Kellyanne Fitzpatrick, an attorney turned pollster who’s now a Trump consigliere and goes by her married name, Conway. Olson wrote that Comstock would often work until 4 am in a tiny first-floor room of the Rayburn House Office Building that was so secure that even the cleaning room didn’t have keys.

Friends of Comstock’s don’t like to talk about it, but her boss at the Reform committee, former Indiana Republican congressman Dan Burton, was a true Clinton conspirator. In his own back-yard version of the Warren Commission Report, Burton shot a watermelon (some contend it was a pumpkin) to test whether the 1993 death of Clinton aide Vince Foster was a suicide or, as feverish and repeatedly debunked stories on the far right alleged, a murder. In 2001, the Washington Post dubbed Comstock, by then a Republican National Committee dirt-digger, “a one-woman wrecking crew.” (By 2016, the establishment paper’s editorial page was endorsing her for a second term.)

During this time, Comstock also became close with David Bossie, the conservative activist who served on the Reform committee with her and later became head of Citizens United and Trump’s deputy campaign manager. Comstock is godmother to Bossie’s eldest daughter.

David Brock, the anti-Clinton writer who turned into a liberal Clinton champion, described how Comstock came by his home during one set of Clinton hearings “to watch the rerun of a dreadfully dull Whitewater hearing she had sat through all day. Comstock sat on the edge of her chair screaming over and over again, ‘Liars.’ ” That may be hyperbole from an admitted fabulist who has renounced much of his younger writings, but if you watch Comstock on the C-SPAN archives, her Clinton contempt is palpable. At a meeting of conservative women in 1998, she dismisses the idea of Congress censuring Bill Clinton, the kind of middle ground that most Americans favored, fuming that “if not for a blue dress and a girlfriend telling her she looked fat in it,” Clinton might have gotten away with his affair with the intern. Comstock really believed he should have just resigned, Corallo told me: “For her, it wasn’t that he was messing around with this woman and that woman. It was that instead of doing the right thing and resigning for the good of the country, he set America on an irreconcilable course.”

Still, despite Comstock’s partisanship, many in the media found her reliable. “Facts were our bread and butter,” says Betsy Fischer Martin, the former executive producer of Meet the Press who became a friend, too. “She was very aboveboard and never tried to pull a fast one.”

As the Clinton wars wound down in the late 1990s, Comstock moved to the Republican National Committee, where she ran the research department, putting together voluminous volumes on Al Gore. She was in Florida in 2000 to help with the election recount that won George W. Bush the presidency, then served in his government as Department of Justice spokesperson, working under the man who may have been the administration’s most polarizing culture warrior, attorney general John Ashcroft.

Back in the private sector, Comstock worked at Blank Rome, a law firm where she was a registered lobbyist for the likes of Koch Industries, the Canadian Cattlemen’s Association, and a pro-immigration group on Cape Cod, where her parents have a home. Comstock “made it clear she could get the real right-wingers, the crazies, onboard,” says one Democratic lawyer who worked with her on an issue for a well-known tech company.

She also worked on another high-profile political/legal skirmish, this time defending the insider who claimed to be a victim of partisan prosecution, joining with Corallo to help defend I. Lewis “Scooter” Libby, Vice President Dick Cheney’s chief of staff. Libby was convicted of obstructing justice in 2007 and was pardoned by President Trump earlier this year. I was one of several reporters called by the prosecution in the case.

“She’s been underestimated by the left before—they’ve made her their number-one target,” says a longtime friend who lives in the 10th District. “But she’s just very, very effective and out there all the time on local issues. That Dan Burton stuff is ancient history.”

Many insiders who switch from operative to candidate believe they’re entitled to start at the national level. But when Comstock made her first run for office in 2009, it was for the Virginia statehouse. She spent five years working on close-to-home issues in the relative obscurity of Richmond before her old mentor, Frank Wolf, retired from Congress in 2014. She ran for the job and won by 16 points.

In the House, Comstock has walked a line between being a good member of the GOP tribe and representing a district heavy on government employees and political pragmatists. She voted for the Republican tax-cut package, even though it curtails the state and local tax deduction that’s so widely used in her district, and backed GOP spending cuts. But she didn’t vote for the 2017 repeal of Obamacare. She’s among the House’s top ten recipients of National Rifle Association money and gets an A rating from the pro-gun group. She opposes most forms of legal abortion. “I think Roe v. Wade should be overturned,” she said on MSNBC’s Hardball, in a clip that got replayed often by her opponent in 2016 and will surely be in heavy rotation this fall. She gets dismal grades from some of the biggest environmental groups. The website FiveThirtyEight, run by statistics expert Nate Silver, examined House districts and how their representatives vote; it found Comstock to be the second-most ideologically out of touch with her constituents.

One reason Comstock may survive is because she’s hustling every day, fueled by that work-harder-than-the-boys ethos. Comstock is everywhere in the 10th. She was out on the streets with the Northern Virginia Regional Gang Task Force last summer in Sterling when they picked up a suspected member of MS-13. “She understands the issues,” Jay Lanham, executive director of the task force told me, noting that her legislation to give such task forces more money will help. The 10th District used to be overwhelmingly white and more rural; today it’s immigrant-rich with endless pho shops. Thus in late May you could find Comstock at a Punjabi fair and the Heritage Nepal Festival in Centreville as well as at more traditional Memorial Day events in Leesburg, Purcellville, and Berryville. Unlike Trump, she’s well known at mosques such as the giant ADAMS (All Dulles Area Muslim Society) center in Sterling. She has also picked issues designed to tickle the erogenous zones of Northern Virginians. She’s on the science committee and has promoted STEM education.

Rivals unsuccessfully sought to highlight Comstock’s hard-right connections in 2016. Photograph by Jahi Chikwendiu/Getty.

Rivals unsuccessfully sought to highlight Comstock’s hard-right connections in 2016. Photograph by Jahi Chikwendiu/Getty. This year, when she faces Democrat Jennifer Wexton, those ties—and Trump—will again be front and center. Photograph by Steve Helber/AP Photo.

This year, when she faces Democrat Jennifer Wexton, those ties—and Trump—will again be front and center. Photograph by Steve Helber/AP Photo.“There may have been some concern out there that she’d be ideological, but that’s not the case—she works really, really hard,” says Tom Davis, the former Republican congressman from the adjacent 11th District.

“She’s going to be hard to beat,” concedes a Virginia Democratic officeholder who marveled at the Cabinet Room public sparring with Trump.

But while Comstock is good at the grip-and-grin of retail politics, she displays a certain circumspection. She doesn’t do the kind of widely announced, open-to-all town meetings that are painful for members of both parties because they tend to lure organized demonstrators. (Comstock’s office has noted that she does do telephone town meetings in addition to a gazillion events around the district, but those aren’t the same.) She also avoids what are likely to be confrontational situations, skipping, say, a Fairfax NAACP forum for 10th District candidates in late May where she was the only no-show, though she attended other events that day. The Dump Comstock YouTube channel has some pretty damning footage of her avoiding questions, including one in which she cuts off a mild-mannered interlocutor.

Her penchant for control is evident in a somewhat odd but telling document that Washingtonian obtained. Comstock’s office has sent it to those who have invited her to speak. Incredibly detailed and cautious, it asks about who will introduce her, what attire is demanded, even what kind of microphone will be used. (“Pin-On/Lapel? Hand-Held? Attached to Podium,” it asks.) I’ve never heard of any member sending out a sheet with such detail. In June, she spoke out against the crisis at the US/Mexican border in which children have been separated from parents, and her statement was pablum, calling for a “humane, bipartisan solution.” She declined to speak with Washingtonian.

Democrats have Comstock in their sights this fall—an essential bowling pin to be sent flying if they’re to take back the House.

Once a safely Republican canton—it’s been held by a Democrat for only six years since 1953—the 10th District’s changing demographics have made Comstock a top target. In 2016, she defied the district’s pro-Clinton vote but still won by only 6 percent. Jennifer Wexton, the 50-year-old Leesburg lawyer who won the Democratic nomination in a crowded field, captured her party’s optimism when she vowed on Election Night to “repeal and replace” Comstock. In June, the Cook Political Report moved the district from tossup to leaning Democratic. It didn’t help Comstock that she’ll be on the GOP ticket with Senate nominee Corey Stewart, whose stances on Confederate monuments and immigration won’t do anything to improve turnout by the educated suburban Republicans she needs. Trump and Trumpism may doom Comstock.

There will be a certain irony if a volatile President brings down the congresswoman. Her career took off under a much-investigated Democratic President she despised. Now she’s in power, and another louche baby-boomer guy who cuts corners could send it all tumbling. For Comstock, a devout parishioner at St. Luke’s Catholic Church in McLean, to have her future depending in part on the level of Trump hatred has to be frustrating, reminiscent of a line in George Bernard Shaw’s Major Barbara: “I really cannot bear an immoral man.”

This article appears in the August 2018 issue Washingtonian.