Brennan Gilmore wasn’t sure what to do. It was August 12, 2017—the day of the Unite the Right rally of white supremacists in Charlottesville. And he’d just watched a neo-Nazi use his Dodge Charger as a deadly weapon, plowing it through a crowd of counterprotesters and killing Heather Heyer, a 32-year-old paralegal.

Gilmore had been standing just a few feet away. He’d watched the car accelerate into the crowd, and he’d heard “this sickening sound of bodies.” The camera on his iPhone was running the whole time. Now he was back at a friend’s house, wrestling with whether to share the footage online.

Would it trigger even more violence? Would it create a recruitment tool for white supremacists? He texted the clip to some family and friends, asking for advice. Put it up, the replies came back: Rumors were circulating online that the attack was simply a car accident. His video showed the truth.

At 2:13 pm, barely a half hour after the assault, Gilmore uploaded the clip to Twitter and took a slug of whiskey. “Let there be no confusion,” he wrote, “this was deliberate terrorism.”

Video of car hitting anti-racist protestors. Let there be no confusion: this was deliberate terrorism. My prayers with victims. Stay home. pic.twitter.com/MUOZs71Pf4

— Brennan Gilmore (@brennanmgilmore) August 12, 2017

But in the chaotic moments before he hit “tweet,” he never considered that the violence might blow back on him—or that he was about to find himself at the center of a test case about crime and punishment in the age of trolls.

It was supposed to be a quiet summer. Gilmore had taken a leave of absence from the State Department in early 2017 to serve as chief of staff for Democrat Tom Perriello’s campaign for Virginia governor. Exhausted from the unsuccessful primary, the 38-year-old UVA grad retreated to Charlottesville to play his banjo, fish, and figure out his next career move.

Then came the announcement that the alt-right would converge on the college town to protest the removal of a statue of Robert E. Lee. Gilmore felt a moral calling to witness the event: If racist bullies were going to march on his city, he was damn sure going to stand with the community and express his disapproval.

And he did. But that old-fashioned act of bearing witness had a modern twist in an age of ubiquitous video footage.

The clip that Gilmore posted to Twitter caught fire, and he was inundated by media requests. “It was clearly perpetrated by one of these racist Nazis who came to Charlottesville to spread their vile ideology,” he told MSNBC, one of the many news outlets that interviewed him. “His intent was to cause a mass-casualty incident.”

To media covering the calamity, Gilmore made for great content: a lucid observer of a hectic tragedy explaining what had happened to a confused public. His video provided definitive proof that the attack was no accident, something of urgent interest to networks and newspapers. But to the club-carrying, swastika-waving demonstrators and their sympathizers, Gilmore instantly became an insidious spokesman for any enemy of the right—and he deserved to be destroyed.

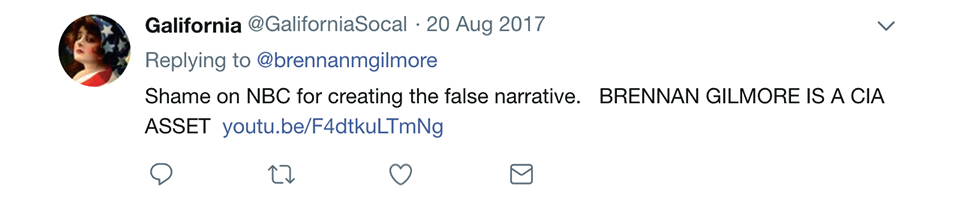

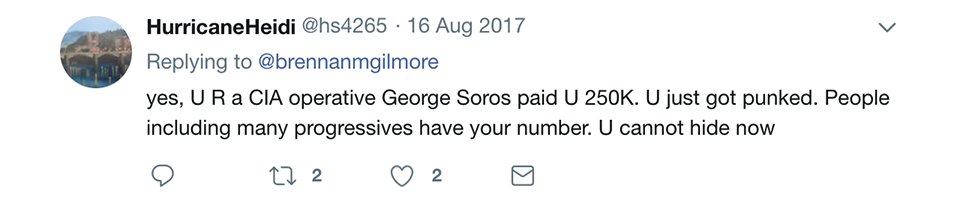

Right-wing extremists were immediately suspicious: Gilmore’s government service in Africa was viewed as a sinister connection to “deep state” forces, and his work on the liberal Perriello’s campaign was proof of a nefarious political agenda. Scott Creighton, of the blog American Everyman, appeared in a YouTube video called “Charlottesville Attack: Brennan Gilmore—Witness or Accessory?,” saying, “He has ties to special operations, special forces, CIA, State Department, Hillary Clinton, and Tom Periello. . . .That’s one hell of a goddamn coincidence, and you’ve got to be a special kind of stupid to buy that.”

James Hoft, whose popular blog, the Gateway Pundit, has 3 million monthly visitors, noted that Perriello’s campaign had received a $385,000 donation from one of the alt-right’s favorite bogeymen: George Soros, the billionaire backer of numerous liberal causes. “The random Charlottesville observer who was interviewed by MSNBC and liberal outlets turns out to be a deep state shill with links to George Soros,” Hoft wrote. “It looks like the State Department was involved in Charlottesville rioting and is trying to cover it up.”

It wasn’t long before America’s best-known conspiracy theorist joined in, too. Alex Jones, whose Infowars website attracts tens of millions of visits a month, appeared in a YouTube video titled “Breaking: State Department/CIA Orchestrated Charlottesville Tragedy,” which featured split-screen images of Soros and Gilmore. “I did research, and I confirmed it all. They had known CIA and State Department officials in Charlottesville, first tweeting, first being on MSNBC, CNN, NBC,” Jones told his audience. “Everybody is a cutout.”

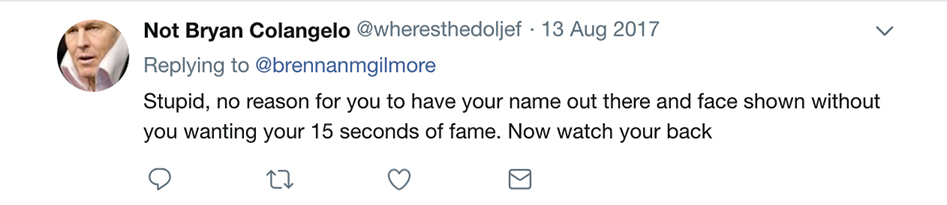

As the fever dream gained traction in the paranoid reaches of the internet, Gilmore’s in-boxes filled with hate mail and death threats. “Brennan Gilmore’s body found in Rivanna River,” read a Facebook comment. “I hope your family feels the violence you protect,” read a tweet. After giving an interview to a reporter at the site of the attack, Gilmore was followed by an unknown man who later interrogated him about his relationship with Soros and Perriello. Says Gilmore: “It made the hairs on the back of my neck stand up.”

Hackers began trying to crack the passwords on his social-media accounts, which he discovered through dozens of security notifications about failed login attempts. Then his sister told him that trolls had mistaken his parents’ address for his own and posted it online. Gilmore grew panicked: Would neo-Nazis now come for his mom and dad? The family arranged for police to patrol their street and asked Gilmore’s brother-in-law, a member of the military, to stay at the house.

One day, a letter addressed to Gilmore arrived at his parents’ home. It was a four-page screed accusing him of being a pedophile and a CIA operative, saying he’d “burn in hell.” As he opened the envelope, a puff of white powder floated into the air. “I didn’t know if it was dried glue,” he says, “or anthrax.”

The substance proved harmless, but the collateral damage was accumulating. Gilmore grew suspicious of strangers and began socializing less often. He started sleeping with a loaded gun by his bed. The stress got so extreme that he developed central serous chorioretinopathy, a detachment of the retina that distorted the vision in his right eye. Googling his name turned up articles about a shadowy CIA operative intent on overthrowing the government. Potential clients of his new business venture, in rural workforce development, chose not to work with him on account of the baggage.

By last fall, Gilmore was fed up. He wanted to fight back against the trolls. But how?

It’s a question being asked at workplaces and dinner tables around the country. Parents of children murdered at the 2012 Sandy Hook school shooting have been harassed by internet extremists who insist the tragedy was engineered by the government to promote gun control. Comet Ping Pong, the Northwest DC pizzeria, found itself smeared by a conspiracy about a supposed sex-trafficking ring tied to Hillary Clinton. In 2016, an adherent of the conspiracy fired a gun inside the restaurant on a Sunday afternoon.

But as these and other unwitting victims have found, getting real-world accountability for virtual harassment is complicated and demoralizing. The frustration starts with what many people consider their first line of defense: the police.

Consider what happened this spring to HuffPost reporter Luke O’Brien. After O’Brien wrote an article that outed the person behind a prolific anti-Muslim Twitter handle, right-wing trolls bombarded him with death threats. He presented a binder containing the worst of them to law enforcement. (He won’t name the agency because of safety concerns.) Although police were eventually responsive and helpful, it was initially tough to get their attention: Weeks passed without any word from the detective, even after O’Brien followed up multiple times. It wasn’t until a local lawmaker contacted the police chief on his behalf that he heard back from the department.

Part of the problem is the way the laws are written. The federal government and most states have enacted anti-cyberstalking statutes that bar repeated use of electronic communications to frighten others. But during an online hate storm, individual members of the mob might send only one or two threatening messages each—not enough to constitute a pattern, as the laws require, says Danielle Citron, a University of Maryland law professor and the author of Hate Crimes in Cyberspace.

On the flip side, the volume of threats in a troll frenzy can overwhelm police even when they are unlawful. “What do you do when you have 200,000 threats?” Citron says. “What do you say to law enforcement? Go arrest all of them?”

After one of Massachusetts congresswoman Katherine Clark’s constituents became a target of the 2014 “GamerGate” harassment campaign and received so many rape and death threats that she fled her home, Clark contacted the FBI on the woman’s behalf. The agency was unresponsive, Clark says. “They really told us quite clearly it wasn’t a resource issue for them. It was one of priority,” she says. “I think there’s still, in certain law enforcement [agencies] and the judiciary as well, an idea that these are virtual crimes that don’t have a real-life impact.”

That inaction creates a vicious feedback loop. It’s the trolls who are empowered, says Mary Anne Franks, a University of Miami law professor and president of the nonprofit Cyber Civil Rights Initiative. “We don’t have a lot of high-profile punishment of these people, so your average troll decides, ‘Well, I can do this, too. There’s zero incentive for me to withhold my impulsive feelings or malice against this person, so I will just do everything I can to destroy their lives.’ ”

When law enforcement won’t help, citizens always have another option: hit the bad guys in the wallet. But it’s not that easy. The forensic work of identifying anonymous online perpetrators is expensive, and many attorneys won’t take the cases because the individual trolls usually don’t have much money to cough up even if you can find them.

The digital players who do have money, meanwhile, are often untouchable. The Communications Decency Act has been interpreted to almost completely shield the likes of Twitter, Facebook, and Reddit from liability for the actions of their users. Another complication: Only a few states have civil laws against online harassment, and there’s no federal civil statute in place, so the plaintiffs now proceeding with these cases—often with the help of nonprofit organizations—are being forced to ask courts to apply longstanding legal theories to their uniquely modern circumstances.

Take the case of Tanya Gersh, a Montana real-estate agent whose life was upended after a business dispute with the mother of white-supremacist leader Richard Spencer. According to her lawsuit, Gersh suggested to Sherry Spencer that she consider selling a building to avoid potential fallout from her son’s political activities. Spencer used the blogging platform Medium to push a different narrative: that Gersh tried to force her out. Neo-Nazi publisher Andrew Anglin went on to post more than 20 articles amplifying that claim on his website, the Daily Stormer, and urging readers to target Gersh, who is Jewish. “Are y’all ready for an old fashioned Troll Storm?” he wrote. “It’s that time, fam.” Gersh, her colleagues, and her 12-year-old son were inundated with hundreds of anti-Semitic threats. “We are going to ruin you, you Kike PoS [piece of shit],” read one message. The harassment was so intense that Gersh began losing her hair.

“We don’t have a lot of high-profile punishment of these people, so your average troll decides, ‘Well, I can do this, too.'”

Now she wants a federal court to find that she was the victim of intentional infliction of emotional distress. But to win her claim, Gersh’s attorneys at the Southern Poverty Law Center must show not only that Anglin’s behavior caused their client serious emotional distress but that he could “reasonably foresee the consequences” of his actions—which is where these cases get tricky. Anglin’s lawyers insist that his writings were simply an editorial position on a public dispute, and they allege that Gersh helped plan protests against Spencer’s business—an indication that she condones the very sort of political expression Anglin engaged in. Therefore, the lawyers contend, he couldn’t have foreseen the distress that his readers caused. Gersh won this point: The judge in the case denied Anglin’s request to throw out the lawsuit. So unless the two sides settle, it will likely be up to a jury to decide whether Anglin is liable for his readers’ actions.

Taylor Dumpson, another alleged victim of Anglin’s, is trying a different tack. The day after she became American University’s first African-American student-government president, a masked man hung bananas from nooses on the Northwest DC campus. Anglin then published a photo of Dumpson and the link to her Facebook account, telling his readers to “send her some words of support.” The hate mob quickly materialized. Dumpson says the harassment was so vile that she lost 15 percent of her body weight, missed some of her final exams, and had to be treated for posttraumatic stress disorder. She’s suing Anglin for violating the District of Columbia Human Rights Act of 1977.

Under the statute, it’s illegal to deny anyone the opportunity to enjoy a “public accommodation” on the basis of race. The law is typically applied in cases of housing or employment discrimination, but Dumpson’s lawyers are arguing that because AU allows outside use of its gym and other amenities, the campus is a public accommodation—and that Anglin’s dog whistle to the trolls made it impossible for her to participate fully in it.

Will that argument work? It might. But it will also show just how complex it is to use America’s current laws to combat this most modern form of harassment. Dumpson’s lawyers will have to prove that a private university costing more than $63,000 to attend is the same sort of public accommodation as a restaurant or a park.

That is, once they finally summon Anglin to court. Anglin has eluded Dumpson’s lawyers every time they’ve tried to serve him with the lawsuit—and they’ve been to 13 different addresses.

Now it’s Brennan Gilmore who’s looking for his day in court. He’s got a friend representing him pro bono: Andrew Mendrala, supervising attorney for the Civil Rights Clinic at Georgetown Law. This past March, Mendrala filed a federal lawsuit against Alex Jones, James Hoft of the Gateway Pundit, and Scott Creighton of American Everyman, alleging, among other things, defamation.

To prove the claim, Gilmore will have to show that a defendant was negligent or reckless by publishing false statements, which in turn harmed his reputation. Mendrala is arguing that the defendants spread harmful lies that triggered the online harassment and consequently impaired Gilmore’s health, derailed his job prospects, and jeopardized his safety. “The clear meaning of the articles and videos that were published about him,” Mendrala says, “was just so clearly, demonstrably false.”

The First Amendment makes defamation notoriously hard to prove. The defendants in Gilmore’s case say the statements in question weren’t false assertions of fact but constitutionally protected opinions. Jones saw Gilmore repeating “anti-Trump ‘talking points’ ” on TV, according to a filing by his lawyers. “That aroused [Jones’s] suspicion, which he expressed off-the-cuff in the passionate, hyperbolic, over-the-top style that is characteristic of his radio show and videos. Any viewer would recognize that as his opinion.”

Attorney Aaron Walker says his client James Hoft did nothing wrong when he wrote online that “it looks like the State Department was involved in Charlottesville rioting and is trying to cover it up,” because, as Walker wrote in a filing, “the term ‘involved’ does not necessarily imply any guilty involvement.” Walker notes that his client Scott Creighton is simply by nature less inclined than others to believe that a former Democratic operative would happen to walk by the site of Heather Heyer’s murder at just the right time to capture her killer on video. “Whether this Court agrees with Creighton’s worldview or not,” the lawyer said in a court filing, “there is no question that his skepticism of coincidence is a point of view, and he has an absolute right to express it.”

It’s a powerful defense, invoking the First Amendment in a defamation case—and in this particular one, Gilmore’s opponents may hold additional firepower. Because he spoke to the media about the car attack, they say, the court should treat him not as a private citizen but as a “limited-purpose public figure.” That’s an important distinction because public figures face a much higher standard of proof. They must show not just that the statements about them were false and harmful but that the statements were made with “actual malice”—with full knowledge that they were false or with a reckless disregard for the truth.

What would a ruling against Gilmore on this point mean? His lawyer worries that it would create a devastating precedent. “Every witness to a crime or a terrorist attack or anything else is a de facto public figure simply because they saw something horrible,” Mendrala says. Just think about Gilmore’s fraught decision to tweet his video. “The consequences would be potentially dire because it would make people certainly think twice before sharing what they saw.”

Whether or not the law comes down on their side, troll victims are finding that at least one population is: the general public. Most people may know they’ll never be a famous movie star doing battle with the scandal-sheet media, but nowadays it’s all too apparent that regular citizens could find themselves in this much more contemporary, and much more dangerous, form of media pile-on.

Bill Ogden, a Houston lawyer who’s representing a small group of Sandy Hook parents suing Alex Jones for defamation, says his firm has been overwhelmed with support. People sent thank-you cards and called to ask how they could donate to the effort—some left cash at the office. “As a plaintiff’s lawyer, I can tell you this,” Ogden says. “We’ve never really thought of us as being the line of defense for the public.”

Anti-cyberharassment advocates, meanwhile, are following the cases in hopes that a high-profile victory for any of the plaintiffs might do more than exact revenge on any one defendant—it could serve as a much-needed deterrent to trolls. But they’re also worrying. “If someone like Alex Jones is not determined to be held accountable for his actions—considering how egregious his behavior was and how harmful the impact was—then really there is literally nothing to stop the person who is a little bit less famous than Alex Jones and thinking, ‘Nothing is going to touch me,’ ” says Franks, of the Cyber Civil Rights Initiative.

Gilmore isn’t interested in a settlement—he wants to push the lawsuit as far as he can, even though it’s causing him more trouble. After he filed it, the trolls came back with a vengeance.

This article appears in the September 2018 issue of Washingtonian.

![Luke 008[2]-1 - Washingtonian](https://www.washingtonian.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Luke-0082-1-e1509126354184.jpg)