To see the new Cool “Disco” Dan art installation at the Wilson Building, visitors must put their phones in a bin, pass through a metal detector, and submit to the careful scrutiny of several imposing security guards.

Things used to be different: Back when Danny Hogg—the city’s most famous graffiti artist, known by all as Cool “Disco” Dan—was spray-painting his tag all over town, he did everything possible to escape notice of the law. “He always had the police after him,” says Roger Gastman, a graffiti historian and confidant of Dan’s, who co-produced a 2013 documentary about the famed local figure.

Now Dan’s work is on display in Washington’s most prominent local-government building. The DC Council recently unveiled two of his original pieces in the Wilson Building’s D Street lobby, a tribute to the artist who died in July 2017 of complications from diabetes at age 47.

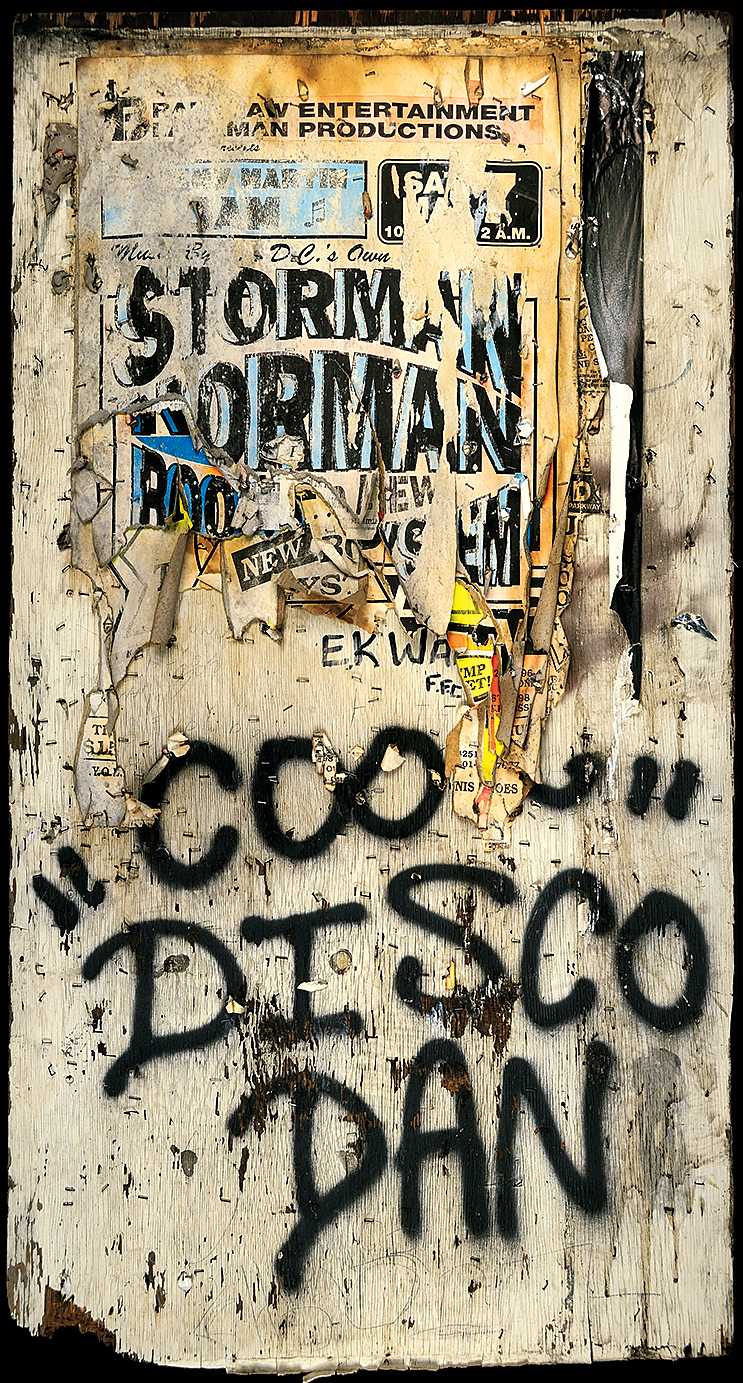

The two tags on display are pretty similar, as was every other “Disco” Dan piece. They’re not colorful murals or complex designs. Dan was a wall writer who simply sprayed his name, criss-crossing the city with an aerosol to put his mark on buildings, under bridges, and on any other suitable surface he could reach, over and over again.

In the ’80s and ’90s, his calling card was everywhere, a vivid emblem of a homegrown DC culture that flowed separate and distinct from the federal buildings and monuments. Then, as boarded-up buildings were replaced with condos and high-end restaurants . . . he was nowhere. So how did Cool “Disco” Dan’s work end up on display in city hall?

If you follow the DC Council’s popular Twitter account, you’re already well acquainted with the work of Josh Gibson, the council’s spokesperson and social-media guru. Growing up in Montgomery County, Gibson spied Dan’s tags all over Metro’s Red Line. He came to realize that Cool “Disco” Dan, and the go-go music Gibson listened to, were unique to DC.

The week Dan died, Gibson asked the council’s Twitter followers if they knew of any surviving tags. A tipster mentioned seeing one on a gray electrical box alongside the Metro. After some searching, Gibson pinpointed its location not far from the Fort Totten station. The box turned out to be owned by CSX railroad, which hadn’t used the thing for years. CSX has little patience for people who deface its property, but Gibson was able to convince them to donate the box and its swipe of spray paint. CSX assistant chief engineer Charles Gullakson sent a crew to salvage it. He admits he found the mission unusual. “It’s just a name on a box,” he says.

Gibson saw it differently. To him, the graffiti was a vital link to an important part of DC’s history, so much so that the local government should put it on display. He cooked up an idea for a Cool “Disco” Dan exhibit in the Wilson Building lobby, a “celebration of local, hometown DC,” he says. Gibson didn’t have any trouble getting approval for the idea, but there was another challenge: What else could he include?

Fortunately, Gibson knew of one other surviving tag. In the ’90s, Gastman, the documentary producer, had spotted Dan’s signature on some beat-up plywood attached to a building on H Street, Northeast. Later on, he pried it loose and took it with him, ultimately donating it to the Corcoran Gallery of Art. Today the piece is owned by the American University Museum, which agreed to lend it to the DC Council. Once dismissed as urban blight, Dan’s work is now considered fine art.

What changed? The city, mostly. As gentrification has reshaped the District, longtime residents, local politicians, and even some newcomers have made a push to recognize and preserve its distinct African-American cultural identity. From Chuck Brown to Ben’s Chili Bowl, Chocolate City institutions are getting public spaces named after them—a way to celebrate DC’s history, sure, but also to deflect discomfort over the significant negative impact of recent changes on a major part of the population.

And while not everyone went to go-go shows or ate half-smokes, anybody who lived here in the 1980s remembers seeing Cool “Disco” Dan’s name all over the place. His work demanded attention and, in a way, created community—a shared experience that was hard to find elsewhere in a city split by race and economic inequality. His work touched everyone.

That makes him worth memorializing, even if some people find it a bit dissonant to celebrate a prolific petty criminal inside the District government’s headquarters. “He meant so much more to the city than a graffiti scrawl,” says Gastman. “He was a symbol of the city, and he still is.”

This article appears in the October 2018 issue of Washingtonian.