One afternoon this past summer, my phone rang. It was an unfamiliar number. When I answered, a frenzied, staccato clamor pummeled my ears—audible bedlam I interpreted as the mystery caller fumbling with the plastic console of an old-school landline. Eventually, the voice on the other end crackled to life.

“Yeah, okay, listen. It’s Sy Hersh. Who the f— do you think I am? Your f—ing wife? What do I look like to you? Your f—ing brother-in-law?”

I took silent inventory and found it unlikely I had confused Hersh, 81, for my in-law—a gay bodybuilder from Florida in his mid-forties—but then again, I’d never met Hersh in person.

“You want me to spend more time with you than my f—ing wife? No way, pal. There’s no f—ing way.”

Now there was silence: A speechless fermata rolled through the phone lines, like the widening wake in the rip-roaring trail of a hijacked rhetorical jet ski. I dug around for a proper response and silently scolded myself for having ignored the warnings about Seymour Hersh. The venerated investigative reporter of My Lai and Abu Ghraib fame—perhaps the greatest in the history of the profession—Hersh is equally known for exhausting his editors, baffling his friends, and wearying his colleagues. He had been described to me as “persuasive,” “flinty,” and “pugnacious”—Washington ciphers better keyed as “abrasive,” “fusty,” and “obnoxious”—and only now, all too late, did I understand that this imploding interview wouldn’t be a joyride but a hostage-taking. This jet ski had room for two.

“The f—? Hello?”

I sputtered back, “It’s good to hear your voice!”—a calibrated reply that, given Hersh’s penchant for maximal volume, carried the added virtue of accuracy. And away we sped.

“No! I’m not going to talk to you. No! I don’t want you to write a profile. I just came back from a f—ing interview I didn’t even know about. I’m going to be in New York through Friday. Same thing is going to happen another week. I have to decide whether . . . . ” He trailed off. “I just don’t want to, okay? Let me ask you a question. Maybe you should have gone to med school, or taken up psychiatry or something.”

The sequence of events went like this: Hersh had recently published a memoir, Reporter. He was hosting an event at Politics and Prose, on a Wednesday. I had proposed we meet there. But Hersh declined. “Too many friends etc. on Wednesday night,” he e-mailed. “Mon/Tues are sane days.” Now I was calling on Monday—Hersh’s designated sane day.

I searched for an amiable deflection: the book event! Too bad we couldn’t meet—how did it go?

“Oh, yeah,” Hersh snapped. “Where were you?”

Hadn’t he said not to come?

“What, are you so dense that I tell you not to come and you don’t come?” I heard what sounded like a finger jackhammering on a desk. “It’s a f—ing question of tradecraft!”

A bit resigned, I asked again how the event had gone.

“Huh? I don’t know. F— the people! I didn’t get out until 10 o’clock, and so—I don’t know,” Hersh said. “Why ask me that f—ing question?”

Yeah, okay, listen. It’s Sy Hersh. Who the f— do you think I am?

This exchange repeated itself for several minutes—me lobbing polite prompts and Hersh body-slamming them down with a kind of signature Seymour Double Suplex. Later, I’d take comfort in learning I wasn’t the only journalist to countenance such treatment. One national reporter recalled an interview with Hersh, by the end of which he was entreating his subject to stop yelling. Another, at the New York Times, recounted the time Hersh repeatedly called him “kiddo.” (He stressed he wasn’t offended.) An investigative reporter in Washington, Christopher Leonard, told me his communication was cut off when Hersh sent him a one-line note saying, “No more f—ing emails.”

Leonard was unfazed. “His abrasiveness is famous,” he said, “but you see that same kind of moralism in his work.” Leonard, who is writing a book about the Koch business empire, continued, “Reporters should be reading this guy’s books from the ’70s and ’80s—all of them—and all of the articles, too, and studying what he did.”

He’s right, of course: For more than 50 years, nearly every national-security or foreign-policy scandal that dogged the American government is daubed with Hersh’s fingerprints. He owned a central role in Watergate, uncovered illegal CIA spying programs, and exposed a stockpile of other seamy government secrets— from covert bombings in Cambodia and the US backing of the Pinochet coup in Chile to Israel’s nuclear-weapons program and the drug-running of dictator Manuel Noriega. Hersh’s reporting isn’t a footnote to history but, often enough, history itself. Yet he has recently pivoted away from breaking stories and toward what his critics—and increasingly his allies—worry is conspiracy-peddling.

In the past five years, Hersh has planted his flag with the RussiaGate skeptics, defended Syrian president Bashar al-Assad from charges of humanitarian violations, and recently claimed he was unconvinced Osama bin Laden planned September 11. All this has refashioned the ardent liberal—Hersh briefly worked for Eugene McCarthy’s presidential campaign—into an overnight hero of the alt-right and earned him appearances on Kremlin-aligned RT television as well as the Infowars show hosted by Alex Jones.

This itinerant path into a dark wood began with a defenestration of sorts. The New Yorker, Hersh’s longtime publisher, declined to run his 2015 revisionist story, “The Killing of Osama bin Laden.” It ran in the London Review of Books instead. But soon Hersh found it hard to publish there, too. In June of last year, Die Welt, a conservative newspaper in Germany, became the latest venue for one of his alternative histories about the Syrian conflict (“Vergeltungsschlag in Syrien,” von Seymour M. Hersh), the only piece he has published during the Trump presidency.

Hersh is obdurately, almost dutifully, sitting out the Trump era. It’s a chapter of political intrigue not seen since Watergate, when Hersh covered Nixon’s downfall for the Times and Woodward and Bernstein dubbed him simply “the competition.” Yet Hersh has preferred to rehash old territory. For the past few years, he was at work on a book about Dick Cheney, until his sources got cold feet, he says. He settled on the memoir instead.

“He swore to me he would never write a memoir,” says Robert Miraldi, a retired SUNY journalism professor whose biography, Seymour Hersh: Scoop Artist, was published in 2013. “You write a memoir, it’s like your career is over. I don’t think he wants to concede that he’s at the end. And he may not be.” Miraldi goes on, “I wish he were knocking on the Russia door today. With Sy’s sources? Sy’s ability to get people to talk? He’d be all over it.” Miraldi sighs. “It’s not what he’s doing now, though.” But why?

“Sorry, can’t help you,” Hersh said before we parted—though not for the last time—“even if it means I won’t sell more books.”

That’s okay. Sy Hersh, after all, is a busy man. Wrong again, Hersh informed me. “An irritable busy man.”

As he writes in Reporter, Hersh was correcting the record practically from the moment he arrived in Washington to work for the AP in 1965. A year later, he got the Pentagon beat. Vietnam was well under way, and Hersh found the building teeming with Harvard-and-Yale-educated war apologists. The 29-year-old was a hog in a moral pigsty and took prized delight in exploding the norms of censorship imposed by the war leadership, and also by his presscorps peers. He relished an opportunity to storm out of the official media briefing, or publish McNamara’s tasteless jokes from a Christmas party. He preferred to get the story from people like him—deep insiders who felt like outsiders, possessed of an acute sense of moral rage. For the next four decades, Hersh’s name appeared on and off various mastheads—“Every place he’s ever gone, he scrapped with his editors,” says Miraldi. He ultimately became a freelance reporter who need answer only to himself. “Hersh is the one guy over on the other side who thinks that everybody in the news, and everybody else, is wrong,” says Tom Rosenstiel, a media critic who leads the American Press Institute.

The vantage served him well. In 1969, Hersh broke the story of the My Lai massacre, in which American soldiers had slaughtered as many as 500 Vietnamese civilians. To pull off the scoop, he combed Fort Benning, Georgia, in search of one of the perpetrators, canvassing in a single day much of a territory roughly the size of New York City—a journalistic feat akin to Wilt Chamberlain’s 100-point game.

The investigative report dramatically changed the perception of the Vietnam War and won Hersh the Pulitzer Prize. It also offered him a chance to stick his finger in the eye of the journalistic elite. Hersh declined an offer from media titan Bob Silvers to publish the story in the New York Review of Books, objecting to the placement of a single paragraph. After syndicating the story through a wire service, Hersh finagled $10,000 in royalties from CBS so the nightly-news broadcast could interview one of his sources. Not long after, Hersh received a call from Abe Rosenthal, editor of the New York Times. The paper had thus far declined to run the freelancer’s story. Now Rosenthal was asking to interview one of Hersh’s sources. Today this might be described as a lucrative networking opportunity. “You want an interview?” Hersh snarled to Rosenthal. “Well, he’s somewhere in New York—find him!” and slammed down the phone.

Seconds later, the phone rang. “Mr. Hersh,” Rosenthal said. “Do you know who I am?”

“Yes,” replied Hersh and slammed the phone down again.

“All the things that Sy is, they’re established in that episode,” Miraldi observes. “He’s driven. He’s maniacal. He’s indignant. He’s terrific at what he does.” Miraldi goes on, “He’s also an extremely difficult guy.” In 1972, Hersh would join the Times, where he unleashed frequent “temper tantrums” on colleagues, called his bosses at home at 3 am, and hurled a typewriter through a window.

But Hersh’s scoops were titanic, his source network the stuff of legend. Occasionally, readers of his memoir are treated to antic accounts of the torment he inflicted on government officials. Nowhere was Hersh more prolific than the world of the CIA. One day in December 1974, William Colby, the CIA director, rang the phone of a Justice Department official. Colby said he would be swinging by for a visit. But the official already knew: Moments before, Hersh had called to tell him. When Colby found out, the miserable director muttered, “He knows more about this place than I do.”

Days later, Hersh published a 4,800-word exposé about the CIA’s erstwhile domestic-spying program. “The Big One,” as he calls the story, would prompt Congress to impose new checks on the intelligence branches, and it sparked a chain reaction of ever more sensational revelations, including MK-Ultra, the CIA’s bungled mind-control program. Yet initially Hersh was widely panned, especially in Washington. Time wrote that there was “a strong likelihood” that the article, littered with anonymous sources, was “considerably exaggerated.” Six months later, the Rockefeller Commission corroborated Hersh’s findings. As the CIA itself would write 20 years later in an unclassified review, “Hersh, and Hersh alone, caused the President, and then Congress . . . to make intelligence a major issue of 1975.” (Hersh received this vindication by taking to late-night television and telling his fellow reporters to “eat crow.”)

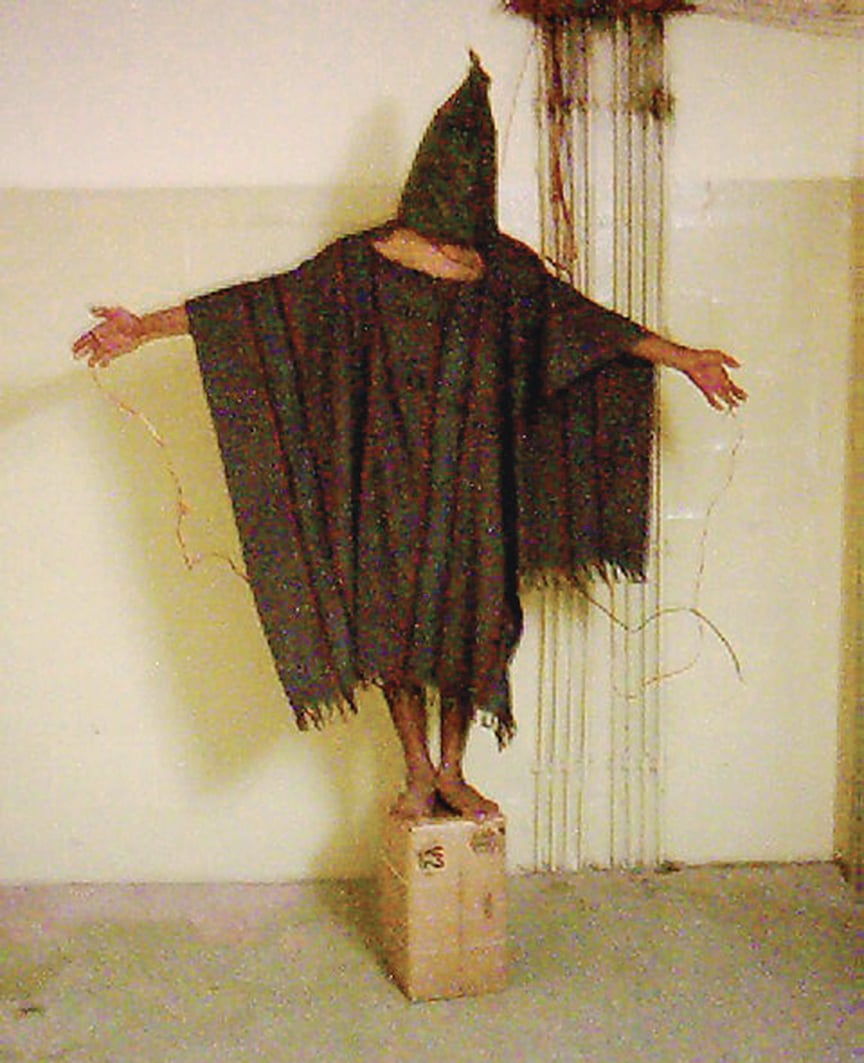

Hersh wasn’t unaccustomed to having his career pronounced dead. Reviewing Hersh’s controversial 1997 book, The Dark Side of Camelot, which made explosive claims about President Kennedy’s sexual and financial misdeeds, author Garry Wills spoke for much of the literary world when he wrote, “Hersh has . . . disassembled and obliterated his own career and reputation.” Seven years later, Hersh was breaking the biggest stories of the Iraq War at the New Yorker—including the harrowing account of wanton prisoner abuse inside the American-run Abu Ghraib detention center. In June 2004, the month after the piece ran, public support for the war flipped for the first time. It never recovered.

“You look at his stories and you look a couple years later, and he’s always right. He rarely gets it wrong,” says Miraldi. “Every now and then, he strikes out, but not much. Nine out of ten times, it’s true.”

In the past 15 years, however, Hersh has threatened to undermine that ratio. In speeches, he suggested, for instance, that the leader of al-Qaeda in Iraq, Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, was a propaganda creation; the US subsequently recovered the jihadist’s body from a bomb strike. In a different talk, Hersh alleged that American military leaders were under the sway of Opus Dei, the conservative Catholic sect, and the sovereign order of Malta, an obscure branch of the church whose primary perks are its own coins and postage. When questioned about such utterances, Hersh has admitted to being looser with facts in his oratory than in his stories. “I can’t fudge what I write,” he told New York magazine in 2005. “But I can certainly fudge what I say.”

All this foregrounded the bin Laden affair of 2015, when Hersh challenged the White House’s narrative of a heroic assassination. His story asserted that bin Laden had been a shut-in prisoner of Pakistani ISI and was given up to the Americans by a high-level Pakistani dissident, rather than ferreted out by the CIA. The 10,000-word article teetered on the testimony of a single American source, anonymous and retired. Afterward, some outlets, such as the New York Times Magazine, lent credence to the possibility of some of Hersh’s findings. But one national-security reporter, Peter Bergen, described the story as a bad episode of House of Cards. Another, Mark Bowden, called it “faked-moon-landing territory.”

Hersh would continue apace. For the next few years, his stories fixated on the Syrian conflict. Many claims hinged on a single anonymous official, and even when sources were named, it wasn’t always reassuring: In a 2015 piece, the first named American source is Michael Flynn, the since-disgraced former national-security adviser, who backed Hersh’s claim that senior military personnel had subverted President Obama’s naive efforts to topple Assad.

It was this story that got Hersh booked on Alex Jones’s show. The conspiracy theorist extolled Hersh, present by phone, as an “amazing person,” comparing his guest’s gallantry to his own. “You’ve had the courage and the fortitude to go through a lot,” Jones said. “The stuff I’ve gone through—I mean, I can imagine.” The episode oozes the cringe-inducing pathos of a guest who has no idea whom he’s talking to. “Stories like [mine] in the mainstream press don’t get copied,” Hersh complained to Jones, “but it doesn’t matter, because there’s the internet—there’s guys like you.” Finally, Jones got down to brass tacks and began ranting, per custom, about the War on Terror and “naked-body scanners on the highway.”

In August of last year, Infowars circulated a leaked recording of Hersh, in which he claims to have inside knowledge that Seth Rich, a DNC staffer who died in an unsolved murder in 2016, had been trying to send documents to WikiLeaks. The conspiracy theory has become a core tenet of RussiaGate skeptics, who believe that the DNC e-mail hack was an inside job by the CIA, that Rich was murdered by the Clintons, or, what the hell, both. “I have somebody on the inside who will go and read a file for me. This person is unbelievably accurate,” Hersh boasts on the tape. “You’re just going to have to trust me.”

The person recording Hersh was Ed Butowsky, a money manager, a guest commentator on Fox News, and a chief provocateur of the Rich conspiracy theory. NPR, in stories about the controversy, asked Hersh the basis for his marvelous claim about Rich trying to reach WikiLeaks. Hersh backpedaled. “I hear gossip,” he said, explaining that he was just fishing for information from Butowsky.

“He’s been pretty out-there lately, in the stories,” Miraldi told me, lamenting Hersh’s flirtation with the fringes. “I almost kind of wish it ended at Abu Ghraib.”

Hersh’s private office, where he has worked alone for the past 27 years, sits in a nondescript building on Connecticut Avenue, a block up from the Mayflower hotel. Just push your way in, one of his friends advised—the only way he’ll respect you. Theoretically.

The door was unlocked. “What are you doing here?” Hersh asked, leaning unctuously in his chair. “You know,” he said, scowling, “sometimes no means no.”

The office looked like the Hall of the Mountain King meets Kramer’s apartment. Along a drab green carpet turned bright lime at the edges, a knee-high permalayer of boxes and books had accreted into all four walls. Hersh wore khakis with worn-out Nikes, and he’d pulled a gray sweater on—but only to mid-chest—so that an inner tube of scrunched wool would accordion its way down throughout our conversation. Finally, after some bartering, he sighed, “Sit down.”

The conversation spouted like a loose water hose, almost Trump-like, in all directions: his son at Vice News, his home-plate seats at Nationals Park, his being courted for a film deal (“A moviemaker—did Brokeback Mountain and Twelve Years a Slave”). At one point, Hersh ignored me and turned on Wimbledon. Otherwise, he seemed pressed to begin any new thought with a disclaimer about people he knows: “I know people on the inside, very smart people, inside.” He then added solemnly, “Mattis writes poetry in classical Greek to his friends,” and forked his eyebrows, as if this proved everything.

Hersh says his sources are keeping him busy. He still holds a rendezvous with a “senior official”—a ritual he’s maintained for 20 years, meeting in a Washington-area home in the early morning hours. Another example: He flipped open his leather-bound calendar to show me where he’d scribbled, “CALL TONY TAGUBA—LUNCH ON THE 25TH.” Major General Antonio Taguba was the Army’s principal investigator on Abu Ghraib and wrote a report that bolstered Hersh’s findings, “a moralist who put his career on the line,” Hersh says.

Hersh acknowledged he wasn’t writing—sort of. “It’s complicated. The critics say I’m not working on much. How would anybody know that?” he said, annoyed. “It’s also a very complicated time to write stories, because the media’s never been so fixed as it is now—fixated, it’s just fixed. We’ve got the people we hate, the people we like, la la la—there’s no middle ground, it seems to me. So it’s a tough time to do stuff.”

Unprompted, he brought up the President. “There’s no focal point for serious reporting. The New York Times is in an all-out war with Trump,” he said. “They’re playing in his little dirty box. It’s all tweet and counter-tweet. They’re not playing to the core issues.” He mentioned Trump’s latest tweet distraction—the President (again) calling on special counsel Robert Mueller to end his probe. “I mean, is it that hard to say, ‘Whew, let’s take a deep thought about this—maybe he wants us to jump on this story!’ ”

This seemed like a corkscrew argument. Besides, wasn’t it Hersh who, beginning with Robert McNamara—“A psychotic liar!” he interrupted—invented the art of calling our leaders, well, psychotic liars?

Hersh seemed to consider this: “So Trump gives an interview. At the end, somebody plays back what he said—and Trump says, ‘I didn’t say that.’ But I remember Johnson put troops in Vietnam for many months in ’65 before he told us.” Hersh raised his palms and let out a cackle both leisurely and rambunctious, and then, with a bravura delivery that put me in mind of Al Pacino, he boomed, “Now that’s what I call a LIE!”

When I tell people I have a good story, they want a good story about Trump. And of course, they don’t really want a good story about Trump.

Shortly afterward, the phone rang. “Yeah. Uh-huh. What? Indicted?” Hersh chuckled. “What, are they all living in the USSR?” Earlier that morning, Mueller had charged 12 Russians with interference in the 2016 election. The indictment was detailed down to the keystroke, by far the clearest evidence yet that Putin had played us. But Hersh refused to buy the story. “Bullshit stuff,” he huffed, hanging up the phone. “This is the f—ing dumbest case you’ve ever made up in your life.” He went on, “I know a lot about Russia. I know a lot about this crazy story that’s going on—the whole notion that the Russians hacked and defeated Hillary. That’s part of something I’ve been working on, something like six or seven years.”

“I’ve got a truck I want to drive through it,” he added. “It’s a comedy act.”

Hersh then did something I’d never seen before: He left the interview to run some errands—asking me to stay put until he returned and leaving me alone in his office to ponder what had just transpired. Bullshit stuff? What if Sy Hersh, rather than giving Bob Woodward a run for his money, had cast his lot with the Watergate skeptics? To most people, earning the courtship of Infowars and RT might be a useful hint about who’s imbibing your ideas. But from whom was Hersh imbibing his ideas?

The office phone rang again. The caller ID blurted out a name—Larry Johnson—and a man left a message. Eventually, Hersh returned and glanced at the answering machine: “I got a phone call?” He cocked a parrot eye my way. “And you didn’t tell me that?” Before I could reply, he blurted, “That’s Larry Johnson. We’re golf buddies,” and added, “Thirty years in the intelligence community.”

I pressed again for a scrap of argument to substantiate Hersh’s RussiaGate theory. No time: He was off to his barber. “I always believe in truth,” he said, gathering up his briefcase. “Sometimes I know truth others don’t. That puts me in a little bit of jeopardy sometimes.”

Later, I looked up Hersh’s man. A CIA analyst in the 1980s, Larry C. Johnson had his last formal posting at the State Department’s Office of Counterterrorism, retiring in 1993 to become a private security consultant. On his now-deleted blog, Johnson mused about whether President Obama was a “c—”; briefly circulated a doctored YouTube video of John Kerry claiming to have raped women in Vietnam; and helped launch the “whitey tape” rumor in 2008, which alleged Michelle Obama had uttered the Caucasian epithet.

More recently, Johnson has been a friendly face on RT and Infowars. Like Hersh, he has questioned whether Syria’s Bashar al-Assad attacked his own people with sarin gas in 2013. Last year, Johnson was a key source for a Fox News story—quickly retracted—that Obama had enlisted the British to eavesdrop on Trump. (Later, reports revealed a grain of truth; the CIA had received British intelligence on Trump associates, but through incidental collection, not by targeting the President.) Johnson told me he still has a top-secret security clearance. The story of Russian meddling advanced by the Democrats, he says, is “100-percent horseshit.”

Hersh, of course, doesn’t reveal his sources. “I just play golf with the guy,” he said of Johnson, later adding, “His views [on] Trump and the various issues are far from mine. By the way, he could be more right than wrong.” Johnson, for his part, confirmed the two have been friends since the ’80s. “He’ll be working on something,” Johnson said, “and we’ll just happen to talk about it, and I can ask him some pointed questions that he may not have thought about.”

Investigative reporters must talk to everyone—authority and heretic alike, with whatever ignoble or unseemly motives they bring. The job also requires a superhuman resistance to the remonstrance of others. Nevertheless, “he should be worried about this,” Rosenstiel cautions. “If you become a useful tool of political operations, suddenly you’re not a soldier in the army of truth. You’re a soldier in somebody else’s army.”

The last time I spoke to Hersh was by phone. By then, Woodward, Hersh’s old rival, had announced his coming book about the Trump White House, and the question felt more pressing: Why wasn’t Hersh working—on RussiaGate, on Trump, on anything?

At last, he relented and began to tell me about a story, in progress for the past two years. “If the election had gone differently, it would be in print. It’s an amazing f—ing story,” he said. “It obviously has to do with you know who, and the Foundation, and Libya. It’s fascinating. It’s a super f—ing story.”

Would Hersh ever write the story about you know who? “It’s too . . . .” He paused. “It’s just too toxic right now. And plus, when I tell people I have a good story, they want a good story about Trump. And of course, they don’t really want a good story about Trump.”

It was hard to listen to lamentations about toxic media from a guest on RT and Infowars. Were they examples, in Hersh’s mind, of a “good story” about Trump? “You have to understand something. I had no f—ing idea who Alex Jones is!” said Hersh. “He kept calling and calling. ‘I don’t know who you are!’ No idea who he is. I didn’t know.” Of RT, he said, “There’s no question they present a different view. But if you think . . . .” He reignited his ludic cackle. “If you think”—cackle—“the United States”—cackle—“media”—cackle—“doesn’t pretend”—cackle—“to represent America more than it represents Russia . . . .”

RT’s sin has never been point of view but sovereignty of thought—some RT reporters have quit live on the air, to protest the Kremlin’s editorial directives. “There’s no question,” Hersh agreed. “But I would also say, as a former press secretary [for McCarthy], I planted a lot of questions in my day, with a lot of reporters willing to buy them.” He laughed. “I don’t know!” Sy Hersh simply could not care less.

Once, when Miraldi asked the late Ben Bradlee about the Watergate era, he couldn’t get the former Washington Post editor to stop talking about “the boys”—Woodward, Bernstein, and Hersh. “You had to f—ing get up early in the morning to beat those boys,” Bradlee said. Would Hersh ever write his own take on Trump and reignite the rivalry?

“Why would I want to? Why do you think I could?” Hersh said. He was silent for a moment. “They’re playing to the Trump haters, though they won’t say that,” he went on. “Bob’s book will probably play the same way.”

Now his voice betrayed the closest Sy Hersh gets to ennui. “I’m much more toxic than you think I am,” he sighed. “No, I crossed a line years ago. When I took out Obama, that’s a line you don’t want to cross with the liberal press in America. I crossed a line—obviously, I’m persona non grata. Or if I’m not PNG, I’m too much of a pain in the ass.”

Woodward has described his Trump investigation as a “rebirth.” But Hersh was on the opposite end of the spectrum: “I’m not unhappy about the world, but I think it’s going crazy,” he said. “It’s a different world. Plus I’m old.”

Miraldi diagnoses all this as symptomatic of Hersh’s contrarian instinct. “In some ways, it’s almost like reflexive with Sy,” he says. While the Fourth Estate bowed to McNamara and Kissinger, Hersh was itching for an ambush. But target the figure most despised by the press corps today? How cliché. Yet even this theory feels incomplete. After all, Hersh had no hesitation pursuing an unpopular George W. Bush administration. Perhaps, after 50 years on the beat, Hersh’s best sources are simply no longer in the game.

In fact, Hersh’s career was always the outlier of a delicately balanced Washington configuration. The political establishment was dour and sane; their lies were rational, in the sense of safeguarding defensible interests, and the media’s honoring of these principles helped manufacture the consensus that became the national narrative. Hersh played an indispensable part—lèse majesté, the court jester who poked at king and courtier alike. But it’s as if the Trump era has suspended this order, stripping bare the true allegiances of all players involved: a liberal “mainstream” press salivating for impeachment, a right-wing media that has abandoned all pretenses and arrayed itself to defend power. No one’s allegiances are more torn than Hersh, a man impelled by the need to confute power, but also the press—a man who can’t stomach liars yet can’t help see the fellow jester who has ascended to the throne without catching, perhaps, a glimpse of himself.

At times, Hersh sounded mystified with this new order—for instance, in describing the press reaction to Trump’s summit with Putin in Helsinki. “Suddenly it’s ‘Treason!’It’s like, whoa, I can’t fit in. There’s no space for me to fit in that hole,” Hersh said, a bit melancholic. “I’m not defending the guy,” he clarified. “On the other hand, I’m not interested in making Trump look better. We’re stuck in this very peculiar situation.”

Before we parted, Hersh left me with one last flourish of Trumpian kabuki. He lowered his voice and described Trump’s “secret plan,” currently under way. Or not. “He may be doing something right under their noses, that he’s going to announce after the midterms.” The Democrats, he said, will “find out they’re going to be flat-flooted. It’s very interesting.”

But, Hersh clarified, “I’m not writing about that, either.”

As he says in Reporter, Hersh “will happily permit history to be the judge of my recent work.” It seems a veiled swipe at his critics and their allegations of loose facts. But some things may require more vision than facts to see. Among the items extracted from the raid on bin Laden’s compound was his extensive personal library. The terrorist seems not to have had much taste for Hersh and owned instead a copy of Obama’s Wars, the 2011 book by Woodward. Elsewhere in the library, however, was another item: the transcript of a Senate hearing on MK-Ultra in 1977. It was held by the Select Committee on Intelligence, the permanent version of the Church Committee—which formed in direct response to Hersh’s CIA exposé. Lately, that Senate committee has been busy with another matter of great national interest: investigating charges of Russian political interference. If some reporters write for the present, and the urgencies and book sales that come with it, others are content to play for a longer legacy.

Correction: Ed Butowski was originally described as a Fox News commentator; he is a guest commentator on Fox News.

This article appears in the October 2018 issue of Washingtonian.