One Tuesday afternoon earlier this year, Matt Cutts, a graying, bespectacled Trump-administration official, was wearing jeans and a black T-shirt saying i regret nothing as he stood before staff in a conference room on Lafayette Square across from the White House.

The head of the U.S. Digital Service listened to reports from employees providing cybersecurity training to Army recruits in Georgia and others assisting FEMA workers in Puerto Rico. Staffers in the room tapped on laptops, a multi-hued, gender-balanced group in T-shirts and hoodies, sporting hipster-length beards and tattoos—tattoos in the shape of the government agency’s logo.

Toward the end of the meeting, Cutts passed out stickers in honor of a departing staffer and announced that the agency’s in-house counsel would soon be taking on new responsibilities. “So if you know a super-smart, tech-savvy lawyer who wants to make a lot less money,” he deadpanned, “send him my way.”

That the scene is more Silicon Valley than West Wing is no accident. USDS was created in part to demonstrate how official Washington might look if it were run like a start-up. Its ranks are filled with people who, by government standards, might as well belong to an invasive species: software engineers, web designers, product managers, and other veterans of the technology industry. “A ragged band of 180 geeks,” as Cutts puts it.

And one minor internet celebrity—maybe you’re one of the 9.9 million who’ve seen Cutts’s “Try Something New for 30 Days” TED Talk.

Cutts was employee number 71 at Google. He took a sabbatical from the web giant in 2016, then gave up his career at the company—along with his stock options—to become USDS’s head engineer, and ultimately its acting administrator. It was somewhat akin to Alex Ovechkin spending the off-season working out with a recreational hockey team in, say, San Antonio, then quitting the NHL to become the rec team’s coach.

But the unconventional profile isn’t the only thing that distinguishes the 46-year-old Cutts in Trump-era DC. Barack Obama hatched USDS in 2014 in response to the bungled rollout of the Healthcare.gov website. By embedding software engineers inside the executive branch, the idea went, you could head off problems at the places where government interfaces with huge swaths of the public. Cutts—a registered Independent—joined the agency under Obama, then stuck around to guide it through the transition to President Trump. He’s still in charge, earning praise from Democrats and Republicans alike, and his squad is one of the few Obama-era initiatives the Trump administration has unambivalently embraced.

How has a soft-spoken, relentlessly genial Obama appointee survived the bombast and brinksmanship of the past two years? Cutts stresses that he has never joined any political tribe. “I got a good appreciation of different points of view growing up,” he says, describing how his mother, a kindergarten teacher and evangelical Christian, insisted that he and his brother attend church every Sunday, even though his father, a physics professor, declined.

Cutts, whose Google career was devoted to bolstering users’ trust in what they search on the internet, sees his current job in similarly lofty terms. “There are so many things that need to be fixed—that’s something everyone can agree on,” he says. “We get to work on projects that matter, that are high-impact and nonpartisan. For me, it’s an easy sell.”

Now he just has to keep selling others like him—even as he deals with an unimaginable personal loss.

A while back, Cutts learned a nerdy name for a philosophy that he pushes on his charges at USDS: “commitment escalation.” It’s something he’s familiar with. When Google went public in 2004, dozens of early hires, now multimillionaires, jumped ship for start-ups, philanthropy, or early retirement. Cutts got rich, too, but stayed on. On the most recent financial-disclosure statement he filed with the Office of Government Ethics, he listed income and assets valued at between $75 million and $228 million.

Cutts, who grew up in Kentucky and learned to program on a Commodore 64, had joined Google in 2000, back when founders Sergey Brin and Larry Page organized weekly roller-hockey games. He scaled the ranks, eventually heading the “web spam” team that worked to prevent third parties from pushing pornography, hoaxes, and other noxious content to the top of search results. He became known for his videos dispelling conspiracy theories about how Google ranked web pages—charges Trump himself recently revived—once recording 70 spots in a single day. And he started a blog that explained the science of search-engine technology but also included investing tips (he’s a devotee of low-cost index funds), images of his Halloween costumes (“Sometimes I get a little too excited”), and his favorite Italian-hoagie recipe (heavy on the sliced meat).

After a decade, Cutts looked for new horizons. A less-than-chiseled specimen, he took up running and within three years completed five marathons and ultramarathons, including a 50-miler. “He wants to do things that are hard and challenging, that other people haven’t thought about,” says Amy Schaumburg, a friend and running partner. Every day for a month, he biked five miles to work as part of a “30-day challenge,” inspired by filmmaker Morgan Spurlock. Cutts chronicled more challenges on his blog: going vegan, not sending e-mail after 9 pm, learning the ukulele. He turned the fodder into an impromptu TED Talk at a conference in 2011—which became one of the most watched TED Talks of all time.

Then in 2014, Cutts informed readers of his blog that he was taking a leave of absence from Google “to be there for my wife more.” Cindy Cutts had initially struggled to adjust to life in Silicon Valley. Matt had promised to spend four years at Google. But some 15 years had passed, so he told her to “pick what’s next.” The couple moved to Omaha, Cindy’s hometown.

Cutts explored a switch to the public sector, including running for office, but Cindy nixed the idea. “She didn’t want her family to be subjected to the scrutiny,” he says. “Besides, I don’t have a chin.” During the 2014 election cycle, Cutts gave $295,000 to Friends of Democracy, a super-PAC that supports public funding of political campaigns—contributions that made him the technology sector’s fifth-biggest overall individual donor.

At another TED conference, in early 2016, Cutts had dinner with Haley Van Dyck, deputy administrator of the fledgling U.S. Digital Service, which was drawing talent from Silicon Valley’s biggest companies, including Google, Twitter, and Facebook. “I was starting to see enough people who I trust and have a lot of stake in going to DC and trying to do something important,” Cutts says. “At some point, I needed to find out what’s going on here.”

The agency taps tech experts for limited tours of duty—three months to two years—allowing them to try government service without leaving their jobs. Cutts’s decision to enlist “was a seismic event,” says Todd Park, the White House technology adviser under Obama. “The best engineers want to work with the best. When Matt joined, it turbocharged our recruiting efforts in Silicon Valley.”

Cutts’s first assignment sent him briefly to Afghanistan to upgrade the system that US military officers use to collect and share information about conditions on the ground. After completing that three-month tour, he extended it three more months, becoming the agency’s director of engineering—another case of commitment escalation. Then a few weeks after Trump won the election, Park invited Matt and Cindy to breakfast at the Navy Mess, inside the West Wing.

The USDS leadership had all been hired under Obama. They didn’t plan to stay after Trump took office. Park told Cutts it was vital that the work continue. Would he take the helm?

Cutts asked, in Valley-speak, “What’s the long-term play?” Park responded that technology could help make some dysfunctional aspects of government work better and in turn restore some of Americans’ trust in its institutions. “Saving society—that was our job,” Cutts says. “It’s a pretty good pitch.”

He still needed his wife’s blessing. “I’m giving you two years from Inauguration Day” she said, “and then we’re going back to California.”

Cutts’s first task: making sure USDS survived. In the months following Trump’s election, about 20 percent of the agency’s 150-person staff departed—some because their tours had expired, but others because of uncertainty about the new administration’s commitment to the work of USDS. “I would have expected half to leave,” says Eddie Hartwig, a former Foreign Service officer who joined USDS in 2016 and is now Cutts’s deputy. “We didn’t know what this White House stood for, and we didn’t know how much autonomy we’d have. But the feeling was probably worse than the reality.”

I just want to say I know it’s hard, and I know there’s a lot of radioactivity.

USDS performs technological rescue missions—fixing the website used by military families to ship belongings when they relocate, for example, or adding a download all button on a web page that handles disability claims, to make sure veterans can access their benefits. “It’s the height of simplicity,” Cutts says, “but each one of these things saves minutes to hours to weeks of effort and lets people see that this is a group that’s trying to help.”

The work also saves taxpayers money—$617 million over five years, in Cutts’s estimate. By that measure, his office’s $19-million budget is a tremendous bargain, one Trump has had no problem getting behind.

“USDS is like a SEAL team of technical experts, and it’s essential that you have someone who other SEALs look up to and respect,” says Matt Lira, who advised Republican House majority leader Kevin McCarthy before joining the White House as a senior official in the Office of American Innovation. “Matt has that technical credibility—but he can also walk into a room with a senior federal-agency official and make his case in terms that a layperson can understand. That’s a rare leadership quality anywhere in our economy. It’s even more unusual in government.” Lira calls Cutts’s decision to stay “a coup.”

Cutts managed to keep much of the agency’s engineering talent onboard. He now spends a lot of his time on the road, holding recruiting roundtables at technology conferences where he makes his pitch “to come try the adventure for a few months.” If it seems like a Sisyphean task—persuading left-leaning tech-industry workers to work under a President who takes regular potshots at big tech—Cutts is undaunted so far. More than half of USDS’s workforce joined since Cutts took over, including dozens of hires this year. “Silicon Valley did lean a certain way in the last election, so we’ve had to adjust our messaging somewhat,” he says, then delivers a version of it: “We’re still working for the American people. We’re still working on things that matter, and it’s still nonpartisan work.”

A wall of posters at the USDS office.

A wall of posters at the USDS office. A collection of Pez dispensers on display at the office.

A collection of Pez dispensers on display at the office.At the agency headquarters across from the White House, stickers cover every inch of available wall space. Bottles of booze sit atop the communal refrigerator. Three fluorescent-lit rooms in the basement serve as conference spaces, with mousetraps conspicuously positioned along the walls. A windowless utility closet filled with servers is labeled the oval office; it may or may not be OSHA-compliant, but Cutts and his team use it for meetings anyway. “It’s a space so crappy, the government didn’t have any use for it,” Cutts says. “So of course we were like, ‘This is perfect!’ ”

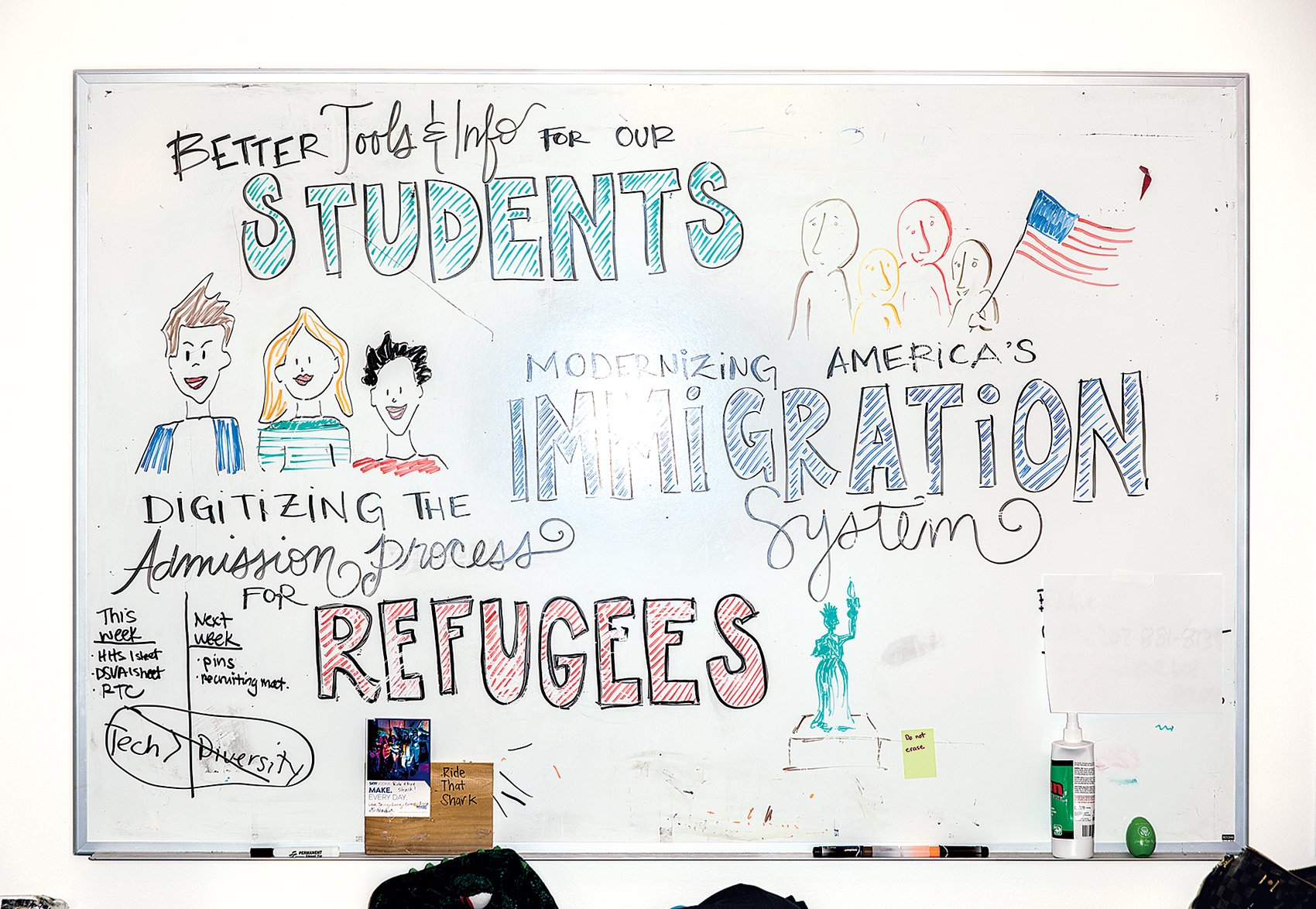

Cutts regularly implores his charges to disregard ideology and “go where the work is.” A recent fix-it project benefited legal immigrants—not exactly a favored constituency of the Trump White House. Three years ago, the Department of Homeland Security unveiled a website where permanent legal residents could for the first time renew their green cards online. “Once it was launched, they celebrated and moved on,” explains Stephanie Neill, who oversees a USDS team assigned to the agency. It didn’t take long before the site was overwhelmed with users, creating a backlog of applications that each still needed to be reviewed by an immigration official. By the time USDS got involved, some 300,000 green-card holders who’d used the service were still waiting to be renewed, some for more than a year. Homeland Security had resorted to putting physical stickers on green cards to signal that the permits were still valid. “As you can imagine,” Neill says, “this was unnerving to a lot of people.”

Neill led a project, code-named Screamin’ Eagle, to streamline the application process. The team optimized the website so it would determine whether an application had been completed, rather than relying on the human reviewer to do so. After USDS’s intervention, the monthly number of green-card holders who have had their renewals processed jumped from 20,000 in April 2017 to 130,000 by the start of 2018. Despite those gains, Neill says the team has encountered skepticism from some Homeland Security officials, who worry that a machine could miss something. Cutts says his staff is always waging a lobbying campaign of sorts: “Our team is really good at saying, ‘Let humans do what humans are good at, and let computers do what they’re good at.’ ”

In an administration focused on shrinking government, that approach has found a willing audience. Case in point: At a recent meeting with officials from the Department of Veterans Affairs, USDS engineers learned that the department planned to purchase 1,000 routers to store data, at a cost of $10,000 each—but if the VA stored more of that data in the cloud, it needed to buy only six. “That was literally one meeting with three people in one afternoon that saved the government $100 million,” Cutts says. “If you’re an engineer or a designer or a product manager, you can’t have that kind of impact anywhere else.”

At the same time, Cutts acknowledges the frustration caused by the turnover of leadership at several federal agencies—or in some cases, the lack of any appointed senior officials at all. On one visit, I watch him grow emotional as he delivers a pep talk to staffers detailed to the Small Business Administration. “You guys are in the trenches,” he tells them. “You’re right on the front lines. And I just want to say I know it’s hard and I know there’s a lot of radioactivity. All those small businesses in the ecosystem that are benefiting from your work don’t know to thank you, but I do. So thank you.”

On March 4, Cutts was in San Francisco recruiting. His wife, Cindy, didn’t like to be alone in DC and had flown to Omaha to visit her family. While watching TV at her brother’s house, she started having trouble breathing. The family rushed her to the hospital. Matt flew in to be at her side, but Cindy never regained consciousness. She died soon after, of acute bronchial pneumonia, at 44.

In a blog post titled “Some terrible personal news,” Cutts announced Cindy’s death. He recounted her love of cats and karaoke, her gift for languages, and her ability to keep him grounded: “I’m unmanned and unmoored without her.”

Cutts spent the next week in Omaha. “I was worried that Matt might not come back,” says Hartwig. “My job was to make sure everyone was prepared for all the eventualities.” At the end of each workday, Hartwig sent Cutts an update. To Hartwig’s surprise, Cutts sometimes replied with feedback.

A week after Cindy’s death, Cutts returned to the office. The USDS staff gave him a book of condolences “and a lot of hugs,” Hartwig says. “But what do you say to that? We didn’t belabor the point. And Matt got back to work.”

His blog post on Cindy’s death elicited 857 messages of sympathy, many from people he’d never met, until Cutts closed the comments section. Over dinner two months later, Cutts tells me he’s dealt with his loss mostly by pushing it aside: “I’m sure I’m distracting myself, and I’m sure there are tough times ahead. But the work has been really therapeutic and really kind of healing. It’s a good way to process things at my own pace and keep myself distracted for a long stretch of the day, and then decide how much I want to think about it.” He was stunned to discover how many friends and colleagues have also lost spouses and “are members of this club that no one wants to join. You don’t really know until something like this happens and people come through in ways you don’t expect.”

I ask whether, after his wife’s death, he considered stepping down. He shakes his head, a thin smile crossing his face. “No,” he says, “because the work isn’t done.”

Cutts asks for the check and gets up from the table. Before moving to Washington, he had never lived in a major city, and he still has a bit of the wide-eyed wonder of a peasant monk visiting Rome. “I love DC,” he says, riding in the front seat of a taxi heading down Constitution Avenue. He lives on Meridian Hill, runs in Rock Creek Park every morning, and rides his bike to the office.

Since Cindy’s death, Cutts has had to “question all my assumptions,” including the apartment they chose and the promise he made her to leave Washington in 2019. He’s open to commitment escalation.

Our taxi pulls up to a patch of grass on the eastern end of the Mall. Cutts pays the $12 fare with a twenty and instructs the driver to keep the change. We jump out and meet up with a group of ten digital-service staffers who are sipping beers and facing off in a game of bocce. Cutts watches his young band of geeks toss balls in the shadow of the Capitol. He can’t stop smiling: “How can you not love these people?”

This article appears in the October 2018 issue of Washingtonian.