This Thursday marks the 45th-annual DC History Conference. So, in the spirit of looking back, here’s a story from Washington’s not-so-happy past.

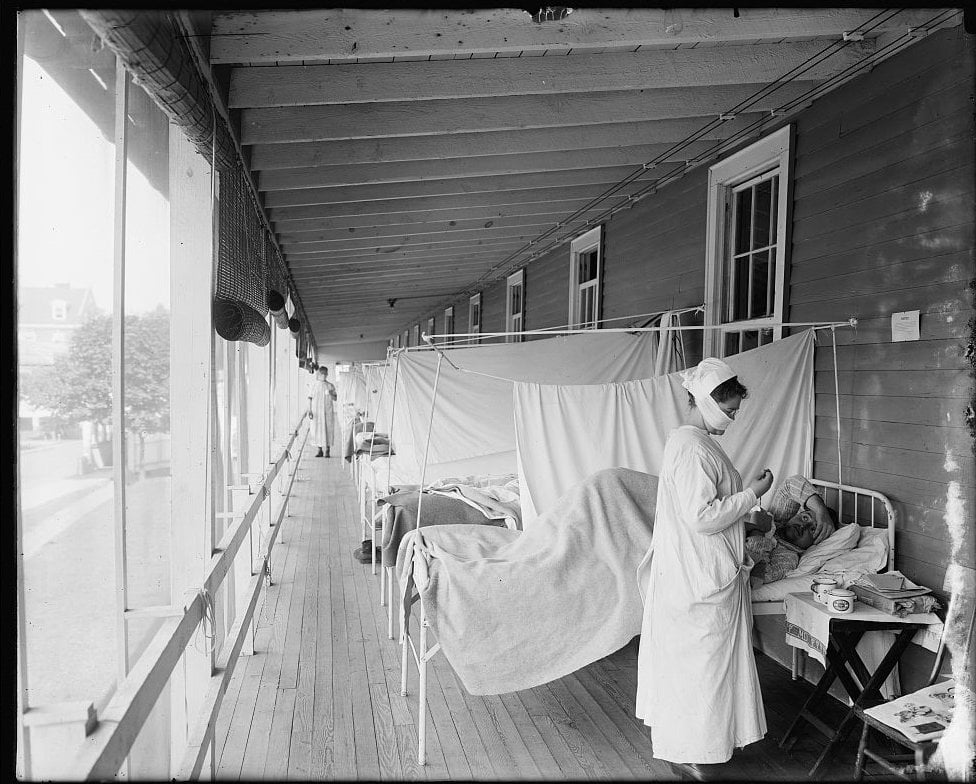

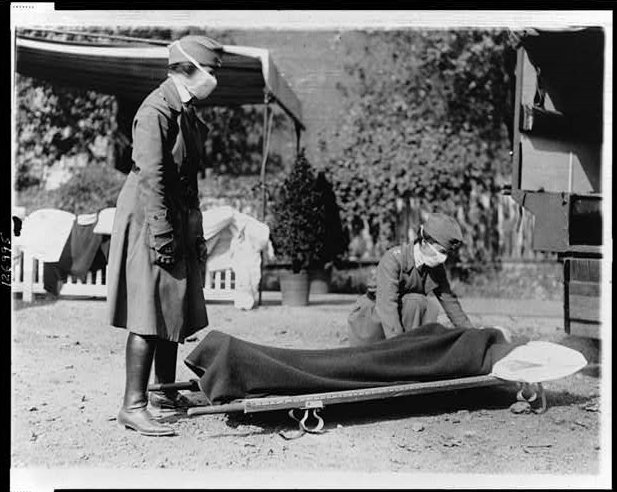

In October of 1918, during the last stages of World War I, major US cities were swept by a devastating wave of Spanish influenza. Washington was especially hit hard: an estimated 50,000 cases were reported from October 1918 to February 1919, affecting more than 10 percent of the city’s population at the time. In total, approximately 3,000 DC residents died on account of the virus.

Dozens of deaths were reported daily. There was a shortage of nurses, gravediggers, and coffins. Playgrounds, theaters, and public galleries were closed, and the USDA’s annual chrysanthemum show was canceled. Advertisements for products such as Pluto Water, a strong laxative marketed as “influenza’s natural foe,” appeared in the Evening Star. And yet, there is a surprising lack of published material on the epidemic in DC, says local historian Matthew Gilmore.

“All the literature on this is basically saying that this whole epidemic is forgotten,” he says. “No one ’fessed up to it.”

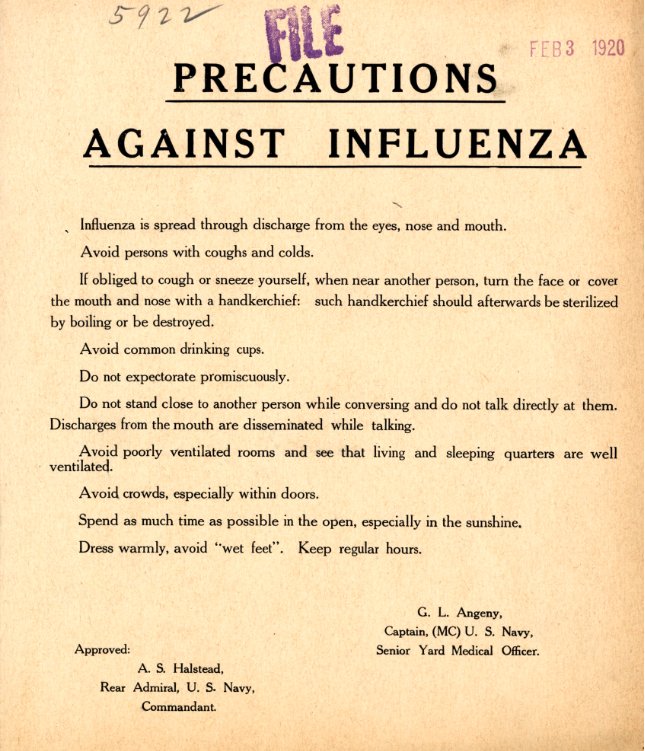

Indeed, obituaries of the leading health officials and nurses involved in fighting the epidemic didn’t mention it at all. The pandemic’s pattern of victims—young adults ages 20 to 40, those who typically have the strongest immune systems—left medical professionals baffled, and thus, unable to provide much research on how to fight it. We’ve since learned more on the science of it, but what about the history?

To find out, Gilmore went back to newspaper clippings from the day, and for all of October, has been providing a day-by-day timeline of the epidemic, tweeting out the death toll. He’s written about the epidemic in a column called “Washington’s Lost Month.”

“No one knew how serious this epidemic was going to be,” Gilmore says. “The past is a foreign country, so the assumptions of health and government were just different back then. They didn’t have the same infrastructure to deal with these kinds of things. And, of course, if you look at the newspapers, there was a big war going on.”

Indeed, with the nation’s attention focused on lives lost overseas, it was the worst possible timing for a seemingly incontrollable catastrophe at home. With an influx of nearly 20,000 people into the city during the war, Washington was overcrowded and a perfect place for the disease to spread quickly and vastly.

Over one 24-hour period, the city reported 91 deaths, but health officials reported the situation as “well in hand,” as a Washington Post article detailed at the time.

Near the end of the month, health officials, reluctant to admit that the situation was out of control, faked confidence and told the public that the disease was simmering down and that calls for physicians and nurses were being “promptly met.”

Specifically, well-respected health officer William Fowler tried to minimize concern and avoid panic, says Gilmore. In fact, Fowler assured the city that the epidemic had reached its crest and would be handled in a couple of days. Fowler would go on to become the health officer in New York City.

The government used careful language to ensure that the care being provided was distinguished from charity or public welfare, and that people didn’t feel like they were accepting government handouts, Gilmore says.

But the seriousness of the epidemic was undeniable, as Congress allocated $1 million to the city and the Red Cross opened nursing centers throughout the city. Perhaps fear and a lack of understanding led to the cover-up. Gilmore has a theory of his own.

“My guess is that they really didn’t fix anything, they really didn’t accomplish anything,” he says. “They allowed it to essentially burn itself out. They didn’t have a solution or cure, so it wasn’t a success.”

This desire to forget a failure has left a gap in Washington’s collective memory. Gilmore writes in his column: “The historical silence over the epidemic seems inexplicable. Perhaps it has been erased from popular memory as simply too horrible and inexplicable to remember.”

But with his recent documentation online, Gilmore has sought to uncover a forgotten history.

“Lots of people use lots of secondary resources and repeat the same stories again and again, and those may not be true, or there’s more depth to them,” Gilmore says. “So I’m looking to find more depth to things.”

A full list of Gilmore’s resources can be found here, and you can find his original post in the Intowner here.